Economic sanctions have become an increasingly important tool of statecraft, but there is still much debate on whether and how they work. Supporters argue that sanctions can help raise the costs to states that threaten international stability, send signals to allies and target countries about the strength of US commitments, and reinforce international norms of good behavior by naming and shaming violators. Critics argue that sanctions rarely induce changes in state behavior, typically impose costs on US firms, and often punish innocent civilians in the target country. With President Trump recently signing bipartisan legislation placing a new round of economic sanctions on Russia, Iran and North Korea and the U.S. Treasury Department imposing new sanctions on several current and former members of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro's regime (including Maduro himself), understanding the impact of sanctions is especially important.

Despite the frequency of this criticism of economic sanctions in Russia and in other cases, evidence in support of the claim is hard to come by. Countries under sanctions, such as North Korea, Sudan, and Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, are not usually synonymous with best standards in public-opinion polling. Russia presents an excellent and rare case for studying how the public responds to economic sanctions. It has relatively high-quality public opinion polling. The Kremlin responds (at times) to trends in public opinion, and respondents are willing to answer potentially sensitive questions despite Russia’s authoritarian political system. One longstanding criticism of economic sanctions is that they induce a “rally around the flag” effect in the target country—that is, they allow leaders to use sanctions as a scapegoat for any difficulties that may or may not have been caused by the sanctions. For critics, Russia presents a prime example. The Kremlin has faced economic sanctions from the United States and the European Union since the middle of 2014, yet nonetheless, President Putin’s approval ratings have stayed in the stratosphere. These high approval ratings are even more puzzling given the poor performance of the Russian economy over the last five years and the historically high correlation between the economy and presidential approval in Russia. As then Trump advisor and former White House director of communications Anthony Scaramucci noted, “I think the sanctions had in some ways an opposite effect because of Russian culture. I think the Russians would eat snow if they had to survive. And so for me the sanctions probably galvanized the nation with the nation’s President.” Others point to Fidel Castro’s long reign in Cuba in the face of crippling US sanctions as another example of a ruler manipulating economic sanctions to increase his political support at home.

I studied this issue in a recent working paper and found little evidence that economic sanctions influenced levels of support for the Russian leadership. […]

Read More | PDF (Titled: "Do Economic Sanctions Cause a Rally Around the Flag?")

© School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA), Columbia University

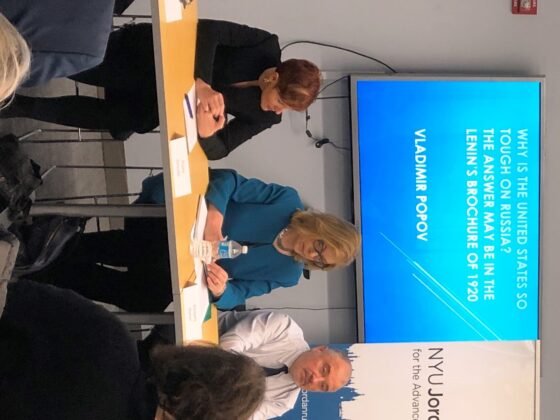

This paper was presented on November 8, 2017, at the joint PONARS Eurasia-NYU Jordan Center conference: "U.S.-Russian Relations One Year After The U.S. Election."