(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) The violent anti-immigrant events in March 2019 in the Russian autonomous republic of Sakha (Yakutia) may foreshadow rising interethnic hostility and an inward turn connected to a crisis of legitimacy for President Vladimir Putin’s regime. While critics have argued that far-right violence is a somewhat contrived feature of Putin’s “managed democracy,” it also reflects genuine social problems in the country. Following the 2014 annexation of Crimea, many far-right nationalists began to see the regime as their champion and to support its policies. Ethnic violence at home declined, even as conflict outside the borders of the country increased. More recently, however, the virtual stalemate in Donbas, the end of “Crimea-is-ours” euphoria, and prolonged economic slowdown have given rise to a more repressive form of authoritarianism that may lead to more bouts of xenophobia and resulting clampdowns on the life and work of migrants. This implies that both ethnic and non-ethnic Russian nationalism smolder and can suddenly flare up, creating a possible short-cut to legitimacy that the authorities may not be able to resist. The return of social explosions like that seen recently in Sakha would have implications for the stability of the Putin regime and the country more generally.

Events in the Sakha Republic

In a recent PONARS Eurasia policy memo, Guzel Yusupova argued that ethnic politics was likely to return in Russia in part because minorities are able to use ethnic issues as a form of resistance to authoritarianism. This issue was clearly on display in March 2019 when allegations of rape drove a pogrom against Kyrgyz migrants in the far-northern region of the Sakha Republic. On March 17, 2019, the arrest of a Kyrgyz migrant for the rape of a Russian girl sparked a spontaneous demonstration in which mostly 200 young people damaged the property of migrants, including many buses and minivans that migrants tend to drive. According to media sources, three people died as a result of the pogrom and more than 20 were hospitalized. The pogrom was followed the next day by a rally at the “Triumph” stadium, attended by an estimated 3,000 (mostly ethnic Yakut) people calling for the deportation of migrants. On the same day as the rally, seven people attacked the driver of a bus, and a group of young people organized a pogrom of vegetable stalls. Subsequently, on March 19, many migrants skipped work and about 90 buses did not go on their rounds to collect people from bus stops. On March 20, the Sakha interior ministry confirmed that several people had been detained in the city for threatening migrants. It also came to light on April 5 that a local Yakut nationalist group, “Us Tumuu,” had played a role in organizing the violence.

The reaction of the authorities to these events has moved from admonition to obedience before the demands of the mob. At the rally on March 18, the mayor of the city pleaded with people in person and later went on television to declare that: “crime has no nationality. There are good and bad people in every nation.” With the governor urging restraint and for the crowd not to allow the actions of one person to lead to interethnic hatred, an environment of intimidation continued against migrants. In a seeming capitulation to the demands of the mob, the governor of Sakha, Aisen Nikolayev, signed a decree on March 27 banning the employment of migrants in the region, although the ban excludes citizens of the Eurasian Economic Union. The ban means migrants will not be able to work in over thirty local economic fields. These include jobs as workers in wholesale and retail, as delivery drivers, as drivers of public transport and taxis, as workers in cafes and restaurants, and as personnel in the sectors of law, accounting, engineering design, and research. It remains to be seen whether the actions of the government are sufficient to prevent further eruptions of ethnic violence in the region.

Pogroms in Today’s Russia: A Short History

Historically, pogroms in Russia have been instigated by the government in order to divert public attention and the blame for social problems elsewhere. The anti-Jewish pogroms (pogrom being a word from the Russian root term “to thunder”) in the late nineteenth century, for example, were an outgrowth of attempts to displace blame for late Tsarist era social problems onto the Jews. Perhaps the most famous text in the promotion of such goals—and an early example of “fake news”—was the infamous Protocols of the Elders of Zion ostensibly published by monk Sergei Nilus.

Since the fall of Communism, relatively small-scale pogroms have been a regular occurrence, really becoming prominent from Putin’s second term as president. The first such pogrom took place in the Karelian town of Kondopoga in 2006 and subsequent ones occurred in Stavropol in 2007, Pugachyov and Moscow in 2010, and the last (until now) being in the Moscow suburb of Biryulyovo in 2013. Other pogroms that failed to get off the ground and incite mass violence were reported in the northern suburb of Khotkovo in 2010 and in the “Ivannikova Affair” of 2003 in Lyublino.

Analysis of the riots, as I argued in my 2016 book, Russian Nationalism and Ethnic Violence: Symbolic Violence, Lynching, Pogrom, and Massacre, shows that in each case what prevented or facilitated conflict was the swiftness of actions from the local government. In some of these cases—most notably Kondopoga and Biryulyovo—the physical presence of the key ideologues of Russian ethnic nationalism, Alexander Belov and Dmitry Demushkin, was offered as a powerful explanation for why violence occurred (i.e., they were able to channel rage). Based on media reports about the violence in Sakha, the words of city mayor Sardana Avksent’eva, “We are on our own motherland, in our own city, as masters of our land, and we need to bring this out,” performed the same xenophobic role, giving voice to popular grievance. Rather than trying to calm ethnic fears, then, the local authorities instead chose to stoke them in a pattern reminiscent of narratives earlier in the Putin years.

Indeed, the instigation of inter-ethnic hatred usually takes the form of highlighting the supposed transgressions or grievance narratives for which the Other is allegedly responsible. The focus on grievances as a cause of ethnic violence was the central insight of my book, which formalized the hypothetical relationship between grievance and the form of violence in the theory of ethnic vigilantism. Asking why ethnic violence took different forms, the “theory of ethnic vigilantism” argues that perpetrators of ethnic violence use it in order to hold accountable (as they see it) the minorities involved in a purported “crime.” In this, the “punishment” would fit the “crime” and drive the fact that ethnic violence takes different levels of intensity and comprehensiveness.

Evaluating this against the case of far-right violence in Russia, a content analysis of far-right websites (most of which have now been removed under order of the Russian Prosecutor General) found that certain minorities were indeed characteristically associated with different levels of crime. Jews were associated with manipulation of the government, people from the Caucasus and Central Asia with property crimes, and the Roma with actions threatening the lives of Russians. One website, associated with Dmitry Demushkin’s Slavic Union, featured naked, supposedly Slavic, decapitated bodies hanging from swing hooks in a children’s playground under the words “killed by blacks.” Women and children were “advised not to look.” The photos were clearly forged (and another example of “fake news” with which people in the West have become increasingly familiar).

A less comprehensive analysis of mainstream television similarly found that stereotypes of ethnic criminality were also abundant, with “Criminal Chronicles” featuring programs with such titles as “The crimes of foreigners in Russia.” One program from the early 2000s showed elaborate Italian art forgers, illegal traders from the Caucasus, and asylum seekers from Africa who had moved to Russia. Through a series of case studies of Russian race riots, I also evaluated the theory vis-à-vis Cossack ethnic violence in Krasnodar. All of the findings provided support for the theory of ethnic vigilantism, which gains new significance given the recent events in the Sakha Republic.

Russian Law on Media Censorship

The discussion at hand throws new light on attempts by the Kremlin to introduce restrictions on the spreading of “fake news” and criticisms of the government. The decline in the number of ethnically-based hate crimes (as measured by Moscow’s SOVA center) coincided with a decline in accusations linking ethnicity to criminality. The 2019 law makes the deliberate and repeated circulation of disinformation punishable by administrative fines. More specifically, upon request of the Prosecutor General, the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology, and Mass Media (Roskomnadzor) will now be able to block “deliberately inaccurate socially significant information disseminated under the guise of reliable messages.” Analysts say that the law greatly increases the power of the executive and introduces into Russia censorship of the Internet for the first time. The irony comes, however, in the notion that Russia is trying to crack down on a practice which, in its modern incarnation, was heavily used in the country, if not invented there.

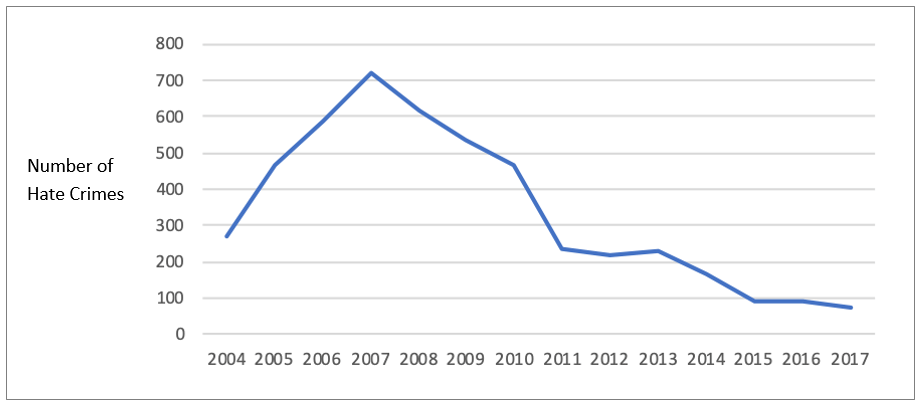

In the first decade of the new millennium, Russia had the highest number of hate crimes in the OECD. The level was so high that the United Nations sent special rapporteur Doudou Diène in 2006 to investigate. That situation has changed somewhat, however, and Figure 1 shows that the number of hate crime victims peaked in 2008 and declined thereafter, with especially notable declines in 2010 and 2014. While other scholars (like Alexander Verkhovsky of Moscow’s SOVA center) attribute this mainly to the changing tactics of the white nationalists, other explanations have to be taken into account also. First, the reform of the Ministry of the Interior’s e-centers (designed to tackle extremism) led to a shift of focus from the North Caucasus to the majority-Russian regions. Second, and most pertinently for this memo, there was a reduced level of ethnic criminal stereotyping in the Russian media as it focused on celebration of the “Crimean consensus.” The forced decline of interethnic grievance narratives in Russian society led to a considerable decrease in the number of hate crimes to the point where, in 2019, they were at levels comparable to other societies.

Figure 1: Number of Hate Crimes in the Russian Federation, 2004-2017 (SOVA Center)

The Importance of the Events

These considerations make the events in the Sakha Republic even more alarming, as the language of Russian inter-ethnic intolerance also shows up in Yakut extremism and with similar results. Likewise, not only was this the first inter-ethnic pogrom since Biryulyovo in 2013, but it also comes at a time of increasing government repression as the political system tries to come to grips with international isolation and economic pain. At a minimum, it shows that ethnic tensions in Russian society are still present and, if one were being speculative, that the authorities in Russia’s electoral authoritarian regime are still dependent on the goodwill of the mob. As the economic situation worsens, such scapegoating is likely to increase. The actions of extreme Yakut nationalists in March may have been the proverbial canary in the coal mine.

Richard Arnold is Associate Professor of Political Science at Muskingum University.

[PDF]

Homepage image credit.