(By Grigore Pop-Eleches and Graeme Robertson) Now that the first shock of the events in Ukraine and Crimea is starting to subside, many in the policy world on both sides of the Atlantic are wondering what happens next. Central among the questions is whether the Russian army will stop in Crimea, or whether Donetsk, Kharkiv or Odessa and even areas with substantial Russian minorities outside Ukraine are next? If you are looking for the answer to that question, you can stop reading now. We have no idea. As we have seen once again in the last few days, political science as a discipline is not very good at prediction, especially about the actions of particular individual leaders or states.

Nevertheless, there are some things that we can be pretty confident about. One of these, as we’ll see in a minute, is that however this dispute works out between Kiev and Moscow, whoever ends up running Crimea and eastern Ukraine in the coming years will face a massive challenge in pulling together a very divided group of citizens. While there may be relatively small differences in some political values, as Pippa Norris argued here Monday, there are very real and highly consequential differences in political identities that make the road ahead in Ukraine in general, and in Crimea in particular, extremely difficult.

The challenges ahead are evident in a survey we carried out of a representative sample of 1,800 Ukrainians in January 2013, before the Maidan. The survey was implemented by the Kiev-based Razumkov Center and focused on issues of language, identity and region. Clearly, subsequent events are likely to have had an effect on views of these issues, but the baseline data we gathered do give a sense of the size of the task at hand.

(Data: Razumkov Center; Figure: Grigore Pop-Eleches and Graeme Robertson/The Monkey Cage)

The picture of political identity in Ukraine that emerges is one of tremendous variation in the degree of commitment to Ukraine as a state. Figure 1 goes to the heart of the issue. Asked an open-ended question about where respondents considered their “homeland” to be, Crimeans, unlike easterners or other southerners, showed fairly little affiliation with the Ukrainian state. More than half of Crimean respondents replied by naming Crimea, while almost no one else mentioned their own region. Some 35 percent of Crimeans did volunteer Ukraine, and while allegiance to Ukraine was higher — around 50 percent — among ethnic Ukrainians and Tatars living in Crimea, these figures were considerably below the support in eastern Ukraine. In short, levels of attachment to Ukraine in Crimea are noticeably out of line with the rest of the country.

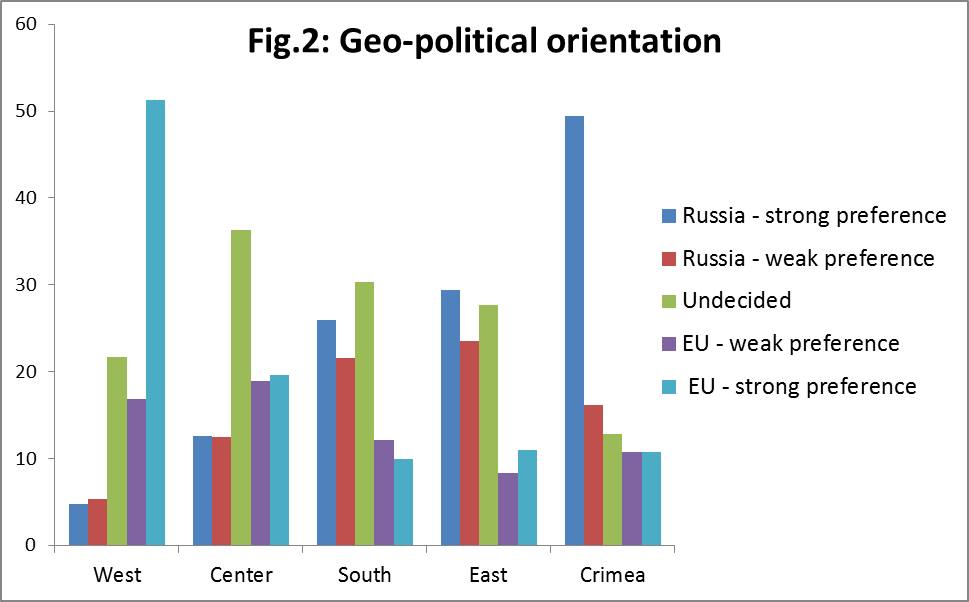

However, it is worth noting that only only 1 percent of Crimeans mentioned Russia as a homeland and only 10 percent mentioned the Soviet Union. This suggests that even though Crimeans have much stronger pro-Russian geo-political preferences than other Ukrainians (see Figure 2) these preferences did not translate into a strong emotional identification with Russia. Moreover, in a more recent Razumkov Center survey (from December 21-25 2013), while substantial minorities endorsed either Crimean independence (35 percent) or joining “another state” (29 percent), a majority (56 percent was opposed to either of the political options involving Crimea’s separation from Ukraine. Of course, it is anyone’s guess how these proportions have been affected by the events of the past two months in the context of a highly partisan political and informational environment.

Data: Razumkov Center; Figure: Grigore Pop-Eleches and Graeme Robertson/The Monkey Cage

One crucial element in this political balance is the issue of language policy. While the 2001 census showed only 58 percent of the population called themselves Russian, in our poll the vast majority of Crimeans spoke Russian at home (see Figure 3) and Crimeans almost unanimously supported official language status for Russian, in sharp distinction to those in the west and cnter who largely opposed it (Figure 4). Given that the language rights of Russian speakers also resonate with a majority of eastern Ukrainians, the recent vote of the Ukrainian parliament to deny regions the right to give official status to languages other than Ukrainian was certainly counterproductive. While the law was ultimately vetoed by the interim Ukrainian president, Oleksandr Turchynov, such symbolic gestures are likely to have a significant effect on the prospects of a political stability and territorial integrity in Ukraine in the near future.

Data: Razumkov Center; Figure: Grigore Pop-Eleches and Graeme Robertson/The Monkey Cage

Data: Razumkov Center; Figure: Grigore Pop-Eleches and Graeme Robertson/The Monkey Cage

It is important to remember that because our sample was nationally representative we have relatively few respondents in Crimea [93]. This is not a representative sample of Crimeans, and while it accurately captures the share of ethnic Russians (about 60 percent), it includes a lower proportion of Crimean Tatars and a higher proportion of Ukrainians than the figures suggested by the most recent census in 2001 (4.4 percent vs. 12 percent and 33 percent vs. 25 percent, respectively). Since Tatars and Ukrainians in Crimea had fairly similar geopolitical preferences, these differences do not significantly affect our overall results, but the results should be interpreted with that in mind.

Still, the results do illustrate important differences between Crimea and other regions of Ukraine that are likely to be politically consequential. Crimeans are broadly opposed to a dramatic westward geopolitical reorientation of Ukraine, and a substantial minority supported either independence or full political union even before February. Much will depend, of course, on how people interpret the tumultuous events that have taken place since our data were collected. Early signs on this are mixed. Reports from Crimea feature some people very supportive of recent Russian actions and some extremely critical, but the balance is impossible to know given the enormous difficulty of conducting reliable polls in the current context. Nevertheless, as these baseline data suggest, the balance of opinion in Crimea is delicate, and there is much to play for in the coming weeks and months.

See the original post © The Monkey Cage