(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) This memorandum reviews Russian state media and civil society responses to the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. The varying reactions cast an interesting light on how Russians view their place in the world and the trajectory of Russia’s democratic development. Russians seem to have a poor understanding of the dynamics of American history and society, but the BLM movement struck a nerve, triggering a heated debate in both state and social media. Studying the reactions to BLM in Russia can teach us a lot about Russian society—just as Russians and others have learned a great deal about American society as the movement has unfolded.

The killing of George Floyd triggered thousands of protests around the world, from the toppling of former slave owner statues in Bristol, England to demonstrations by Aboriginal rights activists in Alice Springs, Australia. However, no such empathetic protests could be seen in Russian cities. This is not because Russian civil society is absent—despite ever-tighter restrictions on public meetings, brave people are willing to take to the streets to challenge things such as the siting of waste dumps or the arrests of investigative journalists. Rather, the BLM movement has exposed a surprisingly troubling attitude towards the politics of race amongst Russia’s embattled democratic activists.

The Impact on Russian Debates

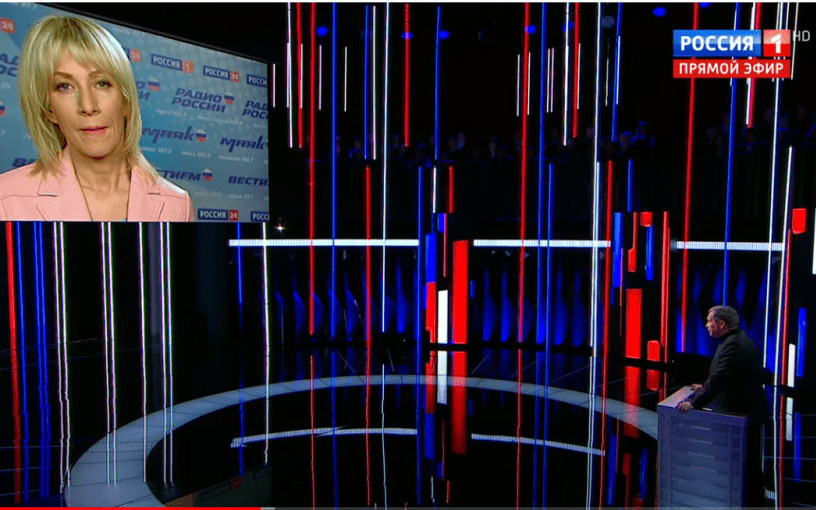

Let us first analyze the responses from official channels. Russian government figures were relatively restrained in their comments—they did not have to say much, preferring instead just to watch America tearing itself apart. In a June 21 interview on Rossiya-1, President Vladimir Putin said, “We always in the USSR and in modern Russia had a lot of sympathy for the struggle of Afro-Americans for their natural rights.” He further added, however, that “If this fight for natural rights, legal rights, turns into mayhem and rioting, I see nothing good for the country.” Federation Council foreign relations committee chair Konstantin Kosachev ridiculed former National Security Advisor Susan Rice for suggesting that the protests were a result of Russian interference (“right out of the Russian playbook”).

Russian TV gleefully relayed images of police violence and burning cities in order to demonstrate the collapse of American society (as did the state media in China). Some of the criticism, of course, is totally justified. Police attacks on protestors, for example, sometimes impacted foreign journalists, including Russians. But much of the media coverage went well beyond objective reporting. Take, for example, the June 7 edition of Vladimir Soloviev’s talk show. Soloviev chuckled at “apocalyptic” clips of a loose police horse in London: “that’s what you get with democracy when it loses its way.” He went on to add, “aren’t white lives important, yellow lives? Are black lives the only ones that count?”

Soloviev’s guests on this show included Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova, who claimed that “sowing chaos abroad, [the Americans] are reaping chaos at home. Those very ideas of destabilization that they were spreading around the world” had blown back on them. At the same time, she hinted darkly that “nothing is accidental,” and it “is useful for someone.” She argued that the U.S. strategy of “exporting democracy” was designed to cover up problems with democracy back home. Soloviev agreed, stating, “the umbrellas of Hong Kong are showing up in Portland.” Maria Butina, the Russian formerly jailed in the United States for working as an unregistered foreign agent, was also on the show. She stated, “these protests are useful for the establishment—racism to order,” used as a part of “speculation for the black vote.” The next day, June 8, Channel 1 screened the iconic Russian gangster film Brat 2 (Brother 2) (2000), set in Chicago—and over the closing credits showed video footage of the current rioting in the United States. The film ends with the song “Goodbye America.”

Russia’s radical nationalist fringe predictably seized on the American protests, which began, of course, amidst the worst outbreak of COVID-19 in the world as well as the worst economic recession in living memory. Conspiracy theorists—never in short supply in Russia—have had a field day with this. One even argued that the Democrats are deploying the technology of “color revolution” on American streets in order to dislodge the Trump administration.

It is interesting to note Russian media reporting on how Russian emigres in the United States have responded to the BLM protests. In “Little Odessa” in Brighton Beach, New York City, Russian bikers gathered to guard local Russian-owned businesses. Similarly, in San Diego, an Armenian restaurant owner recruited Russian-speaking friends to guard his Pushkin restaurant. RT complained that the American press called them “Russian mafia,” and reported that the sign “’Russian mafia in full force’ could be seen in front of the building, defending it from looters.” In fact, that was just a tag on an Instagram photo: no such sign existed. We could not find a single U.S. press source that referred to the “Russian mafia” in reporting on the incident—only Russian sources. This can be seen as an example of self-orientalization, or creating “Russophobia” where it does not exist.

Other Spectrums

Most interesting is the mixed reaction among pro-Western liberals, which shows that the structure of Russian political discourse on race today is very different from that in the West. The leading opposition figure, Aleksei Navalny, has aggressively challenged official media coverage through his YouTube broadcasts, supporting the BLM protests and criticizing police violence inside Russia. Navalny argued that the Kremlin is using the unrest in the United States to distract attention from its own problems, first and foremost, its bungled response to COVID-19.

But Navalny is something of a lone voice. Why have Russian liberals been slow to support and emulate BLM? It is widely recognized that Russian society was traumatized by the experiences of the 1990s, including a wave of violent crime and political battles in the streets that culminated in the shelling of parliament in 1993.

Against that background, it is not surprising that Russians view scenes of looting with alarm, as academic Sergei Medvedev explained in a June 6 Facebook post. What was surprising was that half of the responses to his post—presumably from his liberal friends —were highly critical of the BLM protests. Likewise, many leading ‘liberal’ figures publicly expressed contempt for the peaceful protestors, blaming them for the looting and violence.

Russian liberals remain committed to the language of universal human rights and are disdainful of identity politics (the struggle for rights of marginalized minority groups). For some, the attacks on property were reminiscent of Soviet anti-capitalist propaganda. But racial prejudice is also regrettably a factor. The celebrity and one-time presidential candidate Ksenia Sobchak wrote in a June 4 Instagram post, “Those who realized you need to work your fucking ass off [to be successful] long ago became your Naomi Campbells, your Obamas, and your [Oprah] Winfreys. The rest will always find excuses for their own laziness and stupidity.” (The German carmaker Audi subsequently fired her as their representative.) Investigative journalist and nationalist Oleg Kashin tweeted an image labelled “Martin Looter King.”

Leading libertarian blogger Mikhail Svetov started a Russian Lives Matter movement after a police killing in Ekaterinburg on May 31. The movement focuses on police violence and is not racist, but in an interview with Meduza’s Kevin Rothrock, Svetov was highly disparaging of BLM. Karina Orlova, an émigré journalist writing for the liberal Ekho Moskvy, commented that “Many in Russia and even those who moved from Russia to the US think that dark-skinned people are thieves from birth” and related a recent incident where some African-American kids in Washington, D.C., tried to steal her electric scooter. Even the leading liberal economist Andrei Illarionov, a former Putin advisor who is now a fellow at the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C., devoted a long blog post to analyzing crime statistics to allegedly show that African Americans were not disproportionately targeted by the police.

The whole question of the extent of racism in Russian society is complex, and its historical trajectory is quite different from the rest of Europe or the United States. As Marlene Laruelle points out, Russia has more of a tradition of ethnic/racial mixing than segregation, and the main division in social interactions is between Russians and people from Central Asia and the Caucasus. (It is noteworthy that we have not seen a “Central Asian Lives Matter” movement in Russia.) Some black residents and visitors report no major incidents going about their daily lives, while others experience overt racism, and on occasion, physical violence. In this respect, Russia is probably not particularly different from other European societies—though Russia has a far smaller black community than most West European countries. Racists are, unfortunately, very active in Russian social media. Maria Tunkara, a biracial blogger who complained about racist taunts, is being investigated herself by prosecutors for “spreading extremist materials.”

Yevgenia Albats, one of the few liberals to speak out in support of BLM, said that many Russians are simply unaware of the history of racism in the United States. (The older generation of liberals were exposed to plenty of coverage of racial tensions in the United States by Soviet media, but they discount that as propaganda.) Likewise, veteran journalist (and Putin supporter) Vladimir Posner regretted the racist tone of much of the Russian coverage. New York University professor Eliot Borenstein suggests that Russians are trapped in the narrative that they are victims of history—from the Nazi invasion to the Soviet collapse—and that they don’t want to be told that others (in this case, African Americans) are suffering more than they. Russian activist Ilya Budraitskis argues that this perverse response of the embattled Russian intelligentsia shows that they are trapped in a vision of an “imaginary West.”

For both liberals and conservatives in Russia, both identity and world view are powerfully shaped by attitude toward the United States. This helps explain why BLM has had such a strong impact on political debates in Russia. For pro-Kremlin figures, it was quite easy to incorporate BLM into their narrative, using it to criticize structural racism in America while at the same time echoing racist attitudes. For the reasons outlined above, this was much more challenging for Russian liberals. In recent decades, liberalism in the West has evolved to become a more open and contested discourse, very different from the monolithic grand liberal narrative of the Cold War. Russian liberals remain somewhat trapped in binary categories (the corrupt elite versus their righteous critics) and feel uncomfortable with the self-criticism of contemporary liberalism.

Conclusion

While in the United States and elsewhere there has been a mass movement to dismantle statues of slave-owners and imperialists, the Russian state has, in contrast, been actively involved in building new monuments to tsars and generals in recent years—with some local communities even erecting statues of Stalin. This comes, of course, after the removal of many Communist-era monuments in the 1990s.

BLM has exposed the cancer of structural racism and police violence in American society. But the emergence of such a broad-based movement, which also draws support from the majority white community, shows that civil society in the United States is still strong and raises the prospect of change for the better. That is the main conclusion drawn by Yelena Khanga, a prominent black Russian journalist whose African-American and Jewish grandparents moved to the USSR in 1928. In the words of Sudanese activist Muzan Alneel, “This is not an ugly story of the American dream falling apart. It’s a beautiful story of the propaganda machine falling apart and the true stories of the people’s struggles coming out.”

Peter Rutland is Professor of Global Issues and Democratic Thought at Wesleyan University.

Andrei Kazantsev is Professor at the Higher School of Economics, Russia.

[PDF]

Homepage image credit.