Image credit/license

The interest of major state actors in the Horn of Africa (HoA) and the Red Sea is evident in their basing strategies in the area. Djibouti is the rare state in the region to host several military bases of different states, namely, China, France, Italy, Japan, and the United States. The Sudanese coast has been of interest to external actors, as well, with Qatar, Russia, and Turkey having explored the possibility of establishing a naval presence there. Eritrea, while an isolated regime, has reportedly engaged in occasional defense and security cooperation with Israel, Saudi Arabia, and increasingly Russia. For years, Somalia has been a focus: The European Union’s anti-piracy mission is approaching its sixteenth year, while the competition between Egypt and Turkey has extended to include security cooperation with Mogadishu. The Socotra Islands, the object of a dispute between Somalia and Yemen, hosts the UAE military.

The continued interest of Russia in sustaining a presence in the Red Sea and the HoA is paradoxical, however. Since 2022, the Kremlin’s attention has been monopolized by its war of aggression against Ukraine, started in 2014 and escalated in 2022. Indeed, the Russian economy has militarized, which has squeezed nondefense sectors that might be of interest to foreign partners. International public opinion of Russia has tanked since 2022, and companies, organizations, and governments across the globe are either cautious or negative toward engagement with Russian. Despite these challenges, Moscow has made several moves since 2022 to maintain a global profile, including in the HoA. How does it plan to keep up and build its presence in that region? And why?

Russian Engagement in the Horn of Africa since 2022

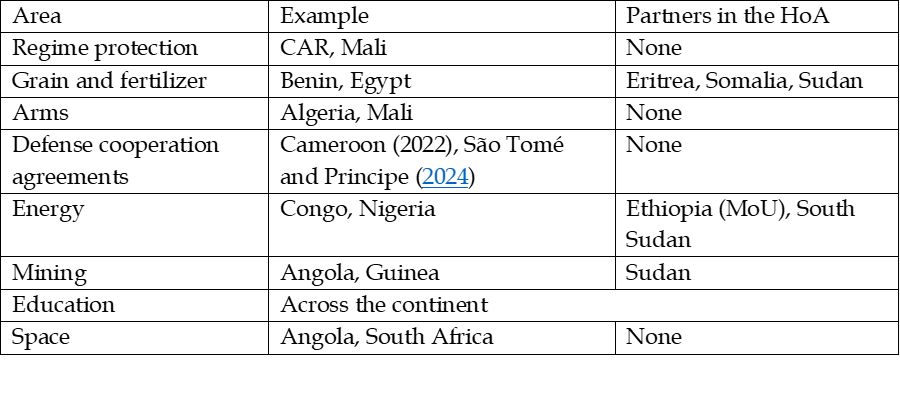

Unlike China, Europe, the United States, or even the USSR, Russia is unable to competitively engage with Africa through trade and investment. Its trade with Africa is relatively small, amounting to $21 billion in exports in 2023, while its investment and aid there is negligeable. Therefore, its quest for influence on the continent relies on a few well-known niches where it remains competitive (see Table 1). The first is “regime sheltering,” where the Wagner Group or Africa Corps provides protection services for governments friendly to Russia. The second niche is grain and fertilizer, of which Russia is a major supplier to the continent. The third is arms. Russia was the leading weapons supplier for sub-Saharan Africa, but its ability to maintain this position has diminished since 2022. The fourth is energy and mining, with Russian companies developing natural gas, oil, and nuclear projects across Africa. The fifth niche, education cooperation, also spans the continent: The Russian government funds scholarships for Africans to study at Russian universities. Finally, Russia has invested plenty of resources in information operations, including state-controlled media like RT, Sputnik and TV BRICS, as well as disinformation operations (see Table 2). Other rising areas include satellite and space technology, and medical technology. The presence of these levers of influence varies across the broader HoA region.

Table 1. Russia’s enduring niches in Africa, 2022-2024

Source: Own data

In the HoA, as Table 1 shows, since 2022, Russia has lacked the levers of influence on which it has come to rely elsewhere on the continent (besides grain). In the region, Moscow has no Wagner Group or Africa Corps deployments, no foreign basing, and no large volumes of trade or investment. With certain exceptions, military cooperation—previously a central element of Moscow’s HoA diplomacy—has been dormant since 2022. Overall, Russian arms sales worldwide have lagged in the 2020s, reaching a low point in 2023. While the HoA states continue to field Soviet and Russian systems, according to SIPRI data, no substantial new deliveries have taken place since 2022. Similarly, no new defense cooperation (“technical-military”) agreements were signed with the HoA states after 2022. Only a 2021 deal inked between Russia and Ethiopia has generated sustained engagement in the form of training missions. Sporadic reports suggest that Russia conducts small training missions with Eritrea too, including after 2022. Russian navy visits to harbors in Djibouti and Eritrea in 2023 and 2024, respectively, have fueled expectations that military cooperation might resume, especially with Asmara. In the past, Moscow pursued in both states its long-standing interest of a Red Sea naval base, but neither effort met with success. (In the Cold War, Moscow operated a naval base in the Dahlak Archipelago, Eritrea, which was then part of Ethiopia.) Only in Sudan has Moscow achieved concrete basing agreements, in 2017 and 2024, although that country’s ongoing civil war creates uncertainty around the outlook for the Russian navy in the Red Sea.

There have been Russian attempts at building its influence across the HoA in other spheres as well. Only Sudan hosts Russian mining firms—many of them once part of the late Yevgeny Prigozhin’s network—with continued Russian interest recorded in 2024. Two Russian energy companies are active in the HoA: Rosatom has signed several memorandums of understanding (MoUs) with the Ethiopian government on peaceful atomic energy cooperation (the latest in 2023), while Zarubezhneft also has a long-standing presence in Sudan, with new exploration blocks awarded in 2022, although the Sudanese civil war has called into question the prospects for these engagements. Cooperation with South Sudan on energy and mining was discussed by South Sudanese President Salva Kiir and Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2023. In August 2024, RusHydro announced several agreements with Juba to develop the South Sudanese hydropower resources. Russia is an active player in the booming African space sector, with Roscosmos establishing partnerships across Africa, including since 2022. Despite fielding programs of their own, the HoA states have yet to engage with Russia in this area. The only development is a recently started Russia-Djibouti dialogue on the topic, although no documents have been signed so far. Reports have suggested that China may pursue a spaceport in Djibouti, potentially raising the stakes for Russia.

Debt forgiveness has played a key role in independent Russia’s foreign policy globally, and Africa is no exception. Since 1991, Moscow has strategically forgiven Soviet-era debts owed by countries around the world, typically as part of arms deals. In Africa, Russian diplomacy trumps the figure of $20 billion of debt forgiven for various states. In recent years, however, the pace of debt forgiveness has slowed, with most of the debt forgiven in Africa attributable to Algeria and Angola, while the only debt forgiven after 2022 was that of Somalia, for $686 million.

Finally, Russian information channels have no assets in East Africa (see Table 2), while, of the HoA states, only Sudan has been the target of known Russian disinformation campaigns in recent years.

Table 2. Major Russian information channels with assets in Africa (selected)

* This does not preclude information from reaching other countries, through distribution agreements, for example.

Source: Own data.

Tentative but unfulfilled agreements, as well as underwhelming results, are the rule for Russian engagement with the HoA states since 2022. Ethiopia, however, is an exception: The two areas where Moscow has seen the most progress toward building its presence in the region are naval cooperation with Addis Ababa and Ethiopia’s BRICS accession. Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has sought to increase access to the sea—currently guaranteed by a deal with Djibouti, which handles over 90% of Ethiopia’s imports and exports. Sea access was also an element of the 2018 peace deal with Eritrea. As part of these efforts, Abiy has sought to create a navy, and over a thousand Ethiopian naval officers reportedly went to Russia for training in 2019. A few years later, in 2022, Russia looked to undermine France as Ethiopia’s leading partner to develop a national navy, principally through training missions and staff education in Russia. Convinced that sea access would be a boon for Ethiopia’s economy, Abiy has alienated neighbors and partners in what is perceived as an increasingly aggressive policy by Addis Ababa. Russian analysts, for their part, see expanded military training as a promising area of cooperation with Ethiopia. Generally, Ethiopia views Russia as a potential supplier in emergency situations, since Moscow adopted such role in the 1998-2000 Eritrean–Ethiopian war. (The same is true of Eritrea, which was also supplied by Moscow during that war.)

Ethiopia’s 2024 BRICS accession has led to Addis Ababa and Moscow opening dialogues on several issues. In the run-up to the Kazan BRICS summit in October 2024, Ethiopian officials took part in consultations on regional affairs and specific items. Ethiopian experts, meanwhile, expect BRICS membership to cause further Western backlash, highlighting potential problems with access to loans and grants, as well as lower foreign direct investment. Membership, then, is principally about signaling a new political course. Since the Tigray war, members of the Abiy government have been under U.S. sanctions, and Ethiopia has gone from a trusted U.S. partner to being expelled in 2022 from the African Growth and Opportunity Act, a measure meant to facilitate African access to the U.S. market and thus spur economic development. Today, Addis Ababa is counting on Russia—and BRICS more broadly—to help restart its economy and break its diplomatic isolation. In turn, Russian analysts have discussed BRICS enlargement into Africa as a way to lock in a “neutral” position by African governments toward Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine.

For Russia, these moves come at a cost. Moscow has spent precious political capital to move the BRICS group in favor of Ethiopia’s accession, since the loose bloc of countries remains divided between supporters and opponents of enlargement. Meanwhile, by supporting Ethiopia’s naval aspirations, Moscow has sided with what is considered an aggressive Ethiopian pursuit of sea access. Should Russia come to be seen as an enabler of Ethiopian aggression, Moscow’s narrative of being a peaceful supporter of African sovereignty would be seriously undermined. In addition, leaning on Ethiopia risks alienating Egypt. While Ethiopia is a long-standing partner of Russia, Egypt accounts for almost 70% of Russia’s African trade and is the site of the El Dabaa nuclear plant, Rosatom’s leading project abroad. As Samuel Ramani has argued, Moscow seeks a balanced relationship with Ethiopia so as not to alienate Egypt, and vice versa.

Why Russia Seeks a Prescence in the Horn: Preliminary Interpretations

Balance of Power (Realism)

Major external actors are struggling to devote attention to their engagement with the continent. Ukraine, Gaza and Taiwan have made it a secondary priority for Europe and the United States. Even though there are several Western military bases on the Red Sea, Europe and the United States are hardly playing a role in settling the civil wars in Somalia and Sudan and are struggling to deal with Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping. For China, slowing economic growth at home and falling investment in Africa have diminished its profile on the continent. In 2024, Beijing promised $4.6 billion in loans to African states, a fraction of the $30.0 billion promised in 2016.

With traditional powers (the West and China) not expanding their presence, Russia might perceive the HoA as open to increased engagement. At the same time, the influence of Turkey and the United Arab Emirates—whose economies are smaller than Russia’s—is rising in the region, along with that of Iran and other Gulf monarchies. Moreover, as argued by Theodore Murphy, the strains in the global order have raised the profile of so-called “middle powers,” like Ethiopia. This shift might make Ethiopia a more attractive partner for Moscow, especially in the context of the former’s strained relationship with the United States, its traditional security partner. Finally, vital Russian exports move through the Red Sea.

Regime Type Preference (Liberalism)

As Alexander Cooley and Daniel Nexon argue, China and Russia are the powers leading the effort to create an alternative international order, where nondemocratic regimes are recognized as legitimate. As the United States “exits from hegemony” and democracy declines worldwide, more governments and actors may welcome this alternative order, believing that it would protect them from the consequences of diminished external legitimacy. Moreover, since 2022, the Kremlin’s long-standing preference for cooperating with authoritarian regimes has been supercharged by Russia’s relative isolation.

The decline of democracy worldwide is felt keenly across Africa, where stories of democratization have become scarcer. In the 2020s, no state in the broader HoA region has seen improvement in its democracy scores, as measured by Freedom House, the Economist Intelligence Unit, and V-Dem. In this context, BRICS acts as an institutional network that can sustain cooperation between states favoring this alternative international order. Governments across the globe have made open bids for BRICS membership, including NATO member Turkey. In the HoA, it is only Ethiopia so far, while the presidents of Eritrea and South Sudan, not members, attended the 2023 BRICS Summit.

Great Power Identity (Constructivism)

As argued by Anne L. Clunan, Russia’s post-Soviet identity coalesced early in the Putin era around great power aspirations, which have widespread support in Russian society, as documented in opinion polls as early as 1992. Since 2022, the Kremlin has openly embraced a messianic concept of Russia’s role in the world, namely, that of Russia being the major power who—through its supposed “proxy” war with NATO—will bring about a multipolar world. For countries around the world, therefore, partnering with Russia means standing against Western hegemony and for a “multipolar” world. This messianic narrative plays a central role in Russia’s engagement in Africa. As Ramani argues, Moscow is undeterred by its relative lack of resources to engage with the continent, nonetheless pursuing the role of a would-be great power in African politics.

From this standpoint, the HoA is part of the emerging non-Western world, with Ethiopia representing the “ancient” cultural core of the region and enjoying a particular affinity with Russia thanks to its Orthodox Christian heritage. This view is echoed by many Ethiopians themselves. (Note that Russia’s majority religion is Eastern Orthodoxy, and Ethiopia’s Oriental Orthodoxy.) This narrative—sometimes embraced by Russian diplomats and state officials—supports further Russian engagement with Ethiopia, even at the cost of influence in neighboring states. As Ruth Iyob argues, Ethiopia’s long-standing sense of regional entitlement is partly because its supposed “ancient” identity blurs the boundaries between Ethiopians and neighboring societies, notably Eritreans.

Conclusions: Persistent Engagement, Limited Impact, the China Factor

Like in the Middle East, Russia’s presence in Africa depends largely on maintaining momentum gained from regular initiatives and high-profile events, as well as taking advantage of opportunities presented by shifts in major power engagement there and local dynamics. In the HoA, these factors are especially pronounced, particularly since 2022, with Russia unable to rely on as many levers of influence as it has in other parts of the continent, such as active arms markets, enduring ties, and military deployments. Despite these limitations, Russia has devoted attention to the region, leveraging the relative isolation of Ethiopia and South Sudan, as well as the pariah status of Eritrea, to enhance its position. The Russian military deployments in Sudan no longer translate into additional reach due to the civil war in that country, which jeopardizes Russia’s broader presence there.

This brief has presented three explanations for why Russia has chosen to maintain and increase its engagement in the HoA despite its limited resources and bigger priorities of Ukraine and Europe. A shifting power balance, combined with enduring concerns over trade routes, might be shaping Russia’s perception of the region as open to engagement. Authoritarian consolidation among the governments of the HoA and their marginalization from institutions led by democratic states might also be a factor, owing to the Kremlin’s preference for authoritarian partners. Finally, Russia’s identity as a major power with a special path in the world might create an affinity for non-Western states that also make conspicuous claims about their “ancient” cultures, such as Ethiopia. These explanations are not mutually exclusive and might reinforce each other. The upshot is that Russia represents an engaged yet limited actor in the HoA.

A factor that might change the trajectory of Russia’s engagement with the HoA is China’s shifting position on the continent. In particular, China’s economic deceleration might lead Beijing to lean more on fora such as BRICS to sustain its continental ambitions, including in the HoA. In turn, its relationship with Russia in Africa might shift, too, moving from a loose division of labor to either competition—especially where opportunities are scarce—or synergy, with Beijing potentially leaning on Moscow’s presence to compensate for its loss of capacity. Ethiopia’s BRICS membership might end up facilitating the latter as the forum increases the opportunities for contact and dialogue on regional affairs among Chinese, Ethiopian, and Russian officials.

Ivan U. Klyszcz is research fellow at the International Centre for Defence and Security (ICDS) in Tallinn, Estonia

Image credit/license