Typically overlooked amid the Kremlin’s gross miscalculations of defender resolve, operational setbacks, and the strategic blowback associated with Russia’s war of choice in Ukraine is the repeated failure of the West’s strategy to prevent or deflect Moscow’s aggression. The sanctions leveled by the United States and the EU did not deter or reverse Moscow’s strategic offensives, and NATO was caught off guard by the amplitude of escalation, de-escalation, and re-escalation of Russia’s successive military exercises along the Ukrainian border and submission of repeated ultimata throughout 2021. U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan acknowledged the challenge and sought to allay anxiety, suggesting that while “we do not have clarity into Moscow’s intentions, we do know its playbook.”

But do we really understand Russia’s coercive playbook? Fusing events data with qualitative analyses reveals that the coercive postures adopted by Russia and the United States were out of sync preceding the Kremlin’s fateful decision to launch a decapitation strike on Ukraine. The strategic discourse surrounding Russia’s military build-up and threats were neither uniform nor transparent. The escalation of Russian belligerence was episodic, varied across domains, did not reciprocate respective counter moves, and was conveyed differently in the Russian and non-Russian press. Although U.S. intelligence ultimately detected the operational signs of an imminent invasion, Russian discourse and practice defied traditional Western assumptions about effective coercive diplomacy, raising questions about the “ways” of Moscow’s strategy. Accordingly, viewing Russia’s statecraft prior to the 2022 invasion of Ukraine through the prism of Western conceptions of military coercion not only over-stated the efficacy of U.S./NATO deterrence, but obfuscated early signals of the hardening in the Kremlin’s posture towards the use of large-scale force.

The Coercive Tangle, January 2021-February 2022

In retrospect, 2021 was the year of coercion between the United States and Russia surrounding Ukraine. Both the intensity and frequency of sanctions threatened by the West were ramped up to deter Moscow from directly using force against Ukraine and to encourage constructive re-engagement in the peace process. Although explicit about the limits to direct NATO military involvement, member states staged military exercises in the Black Sea region, as well as enhanced joint combat training and signed successive arms deals with Ukraine to upgrade the quality of their defensive capabilities that were intended both to reassure Kyiv and to raise the costs to a prospective Russian incursion.

Similarly, there was an intensification of Russian coercive diplomacy directed at both Kyiv and the West. Russia seemingly doubled down on “calibrated” military coercion with large-scale troop exercises along the border to veto closer cooperation with NATO, secure concessions regarding the Minsk II agreement, and exert political control over decisionmaking in Kyiv. Increasingly frustrated by the deadlock in negotiations, recalcitrance of Ukrainian leaders, and security risks presented by prospective forward deployments of long-range missiles, Moscow apparently transitioned by mid-summer from a focus on deterring Kyiv’s closer alignment with NATO policies to compelling the latter’s political submission. This included augmenting the issuance of red lines with oblique threats of using “new hypersonic weapons” and explicit demands on NATO, combined with the marshaling of nearly two-thirds of its military’s battalion tactical groups near Ukraine’s borders. Moscow seemed to back itself into a corner at the end of 2021 by committing to a strong but unsustainable response that put its credibility on the line if its demands were not met.

Yet, the ratcheting up of reciprocal coercion was not tantamount to a steady march to war. In practice, both the frequency and intensity of U.S. and Russian coercive postures fluctuated throughout 2021. There were substantial inconsistencies, with various dimensions of Russian statecraft disconnected from Moscow’s explicit threats and military build-up. This, at times, confounded U.S./NATO statecraft, as Washington appeared self-deterred in April with the cancellation of naval deployments in the Black Sea in the absence of direct threats by Moscow while emboldened to conduct large-scale naval exercises later that summer in the face of increasingly overt forms of Russian compellence.

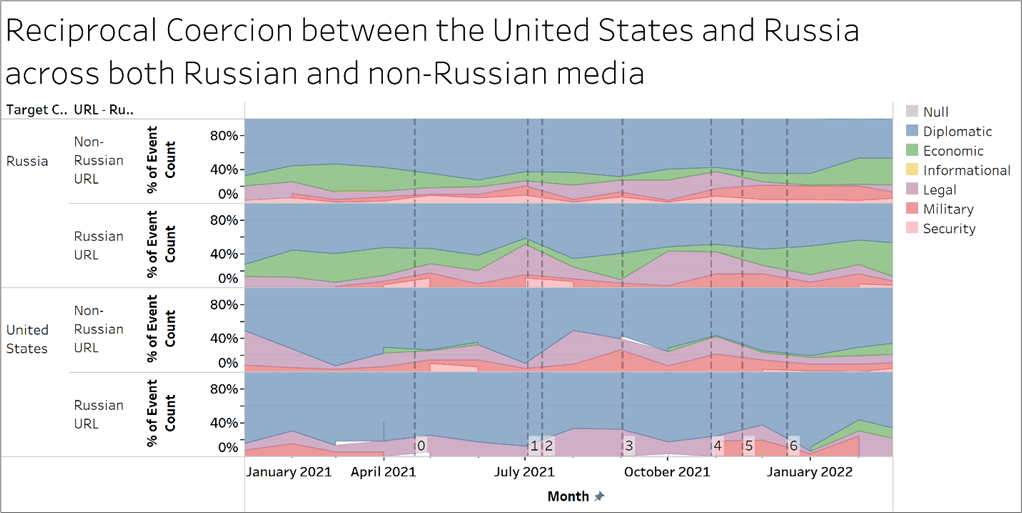

A holistic picture of the multidimensional coercive landscape is illustrated by an analysis of open source events data (GDELT 2.0) that captures the frequency and tenor of popular understanding of respective U.S. and Russian postures conveyed through millions of news articles published across the globe. [1] Applying a subset of event codes (that define select types of action conducted by specific actors) to capture Western-defined coercive discourse, Figure 1 below depicts the bilateral interactive dynamic across policy domains as reflected in both the Russian and non-Russian press. It illustrates the wide range of coercive instruments employed by the United States directed at Russia that favored diplomatic and economic policies, augmented by a basket of legal and military activities that generally held steady throughout the year. Conversely, Russia relied heavily on diplomatic, military, and legal instruments of coercion that were inconsistently directed against the United States. While both sides practiced multidimensional forms of coercion, they engaged asymmetrically in respective efforts to deter and compel.

Figure 1. U.S.-Russian Interactive Dynamic

Intriguingly, the coercive posture surrounding Putin’s explicit warnings against NATO’s crossing of Russia’s red lines in April (see “0” in the figure above) and November 2021 (“5”) varied and was portrayed differently by the international and Russian press. In the former, the April red-line pronouncement was followed by a conspicuous uptick in Russia’s coercive military, legal, and security discourse directed at the United States. This pattern was repeated with subsequent threats conveyed by the approval of Russia’s updated National Security Strategy (“1”), Putin’s essay on the historical “legitimacy” of Ukrainian statehood in July (“2”), and the explicit commitment to protect “Russian citizens” in the Donbas at the end of October (“4”).

The Russian press, however, was virtually silent on Moscow’s military coercive posture through the end of October, notwithstanding the Kremlin’s public threats, steady military build-up along Ukraine’s borders, and hyping of America’s respective coercive posture. The pattern shifted conspicuously following Putin’s red-line statement in November 2021 to match the focus on American economic and military coercion directed at Russia. This contrasted with the drop in coverage of Russia’s military and legal coercion in the international press through the end of the year. Although Russia made international headlines by issuing explicit threats to NATO and mobilizing forces around Ukraine, the shift from deterrence to compellence and the rising intensity of escalation were obfuscated by the inconsistent discourses across domains and media sets.

Unpacking Russia’s Ways of Coercion

The confusion surrounding Russia’s posture prompted focus in the West on discerning both the means and ends of Moscow’s coercive strategy. Attention was devoted to unpacking the Kremlin’s offensive versus defensive motives. Was it driven to restore Russia’s sphere of influence by seeking to reimpose imperial or Soviet claims? Or, was the Kremlin prone to risk-taking to stave off a deteriorating strategic position vis-à-vis NATO or prospects for regime subversion? Similarly, there was debate over Moscow’s preference for wielding cyber, energy, and/or military instruments of coercion. Notwithstanding contending arguments, there was general convergence that the means and ends of Russia’s coercive posture were subsumed by the holistic approach to “strategic deterrence.” The latter is often described as conflating elements of Western concepts of deterrence (upholding the status quo), compellence (altering the status quo), and containment (permanently competing, with no distinctions between peace and war, and no boundaries between the international and domestic realms).

Upon closer inspection, however, a core element of dissonance between Western and Russian approaches rests with the logical underpinnings of the “ways” of coercion embedded in respective strategies. In the Western canon, coercive strategies turn on wielding both material and psychological elements of power to affect an adversary’s perceptions of the costs and benefits of conceding. The premium is placed on reducing uncertainty over national capabilities and political will to uphold threats, and on conveying clear signals as demonstrations of credibility and resolve, including drawing red lines for escalation to brute force.

In contradistinction, Russian strategies of long-term confrontation rest on muddying an adversary’s predicament. The logic turns on using available policy instruments short of exercising physical force to opportunistically target an adversary’s perceptions, sow uncertainty, and manage its reactions. This entails both explicit demonstrations of capabilities to intimidate and blackmail, as well as implicit dimensions for manipulating an adversary’s attitudes, assessments, and values associated with current and future predicaments. The latter implies undertaking indirect, non-linear, ambiguous, and obscured action to exploit asymmetries, suppress an adversary’s will to fight, woo foreign sympathizers, and confuse an adversary’s decisionmaking. These are pursued with the aim of informally orchestrating a target’s reflexive self-alignment with the Kremlin’s political objectives prior to, during, and after the employment of hard military power. Whereas the Western formulation emphasizes demonstrating capabilities, credibility, and commitment to alter the expected utility calculation of an adversary, the Russian approach seeks to shape preferences and processes of an adversary’s decisionmaking such that the rival becomes self-deterred, or otherwise internalizes behavior that is consistent with Russia’s interests.

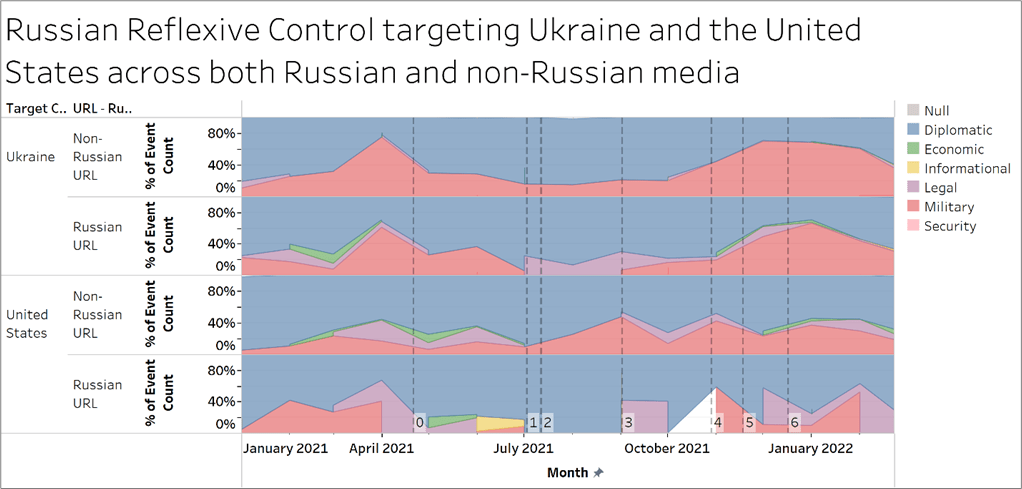

Although difficult to detect, there is some evidence of Russia’s practice of reflexive control that can be gleaned from the events data. By applying a subset of codes to capture actions tantamount to reflexive control, Figure 2 depicts the frequency of Russia’s efforts at framing the narrative of its activities directed at both the United States and Ukraine as covered in Russian and international media. Although generally consistent in its coverage, the Russian press differed with respect to the messaging directed at Ukraine surrounding key events.

Figure 2. Frequency of Russian Framing Efforts

Putin’s approval of a new national security strategy (see “1” in the figure above) and his essay on Ukraine’s statehood in July (“2”) coincided with a change in Russia’s reflexive posture. The Russian press coverage of military-domain activity targeting Ukraine temporarily stopped, while all of its non-diplomatic activity targeting the United States likewise ceased temporarily. This is particularly noteworthy as Russian media would not again frame their activity against the United States as militaristic until November. From July to the end of October, for example, the proxy reflexive control codes did not identify a related action in the military domain conveyed in the Russian media. The September 2 decision to halt cooperation on the OSCE Border and Observer Mission (“3”) presaged the return of military-domain activity targeting Ukraine and a spike in Russian legal activity directed toward the United States. Similarly, the October 29th announcement that Russia would protect its “citizens” in Donbas heralded a military escalation in Ukraine and the return of military-domain activity directed against the United States.

By contrast, international media focused heavily on the military dimension of Russian activity. There was no pause in Russian military-domain activity targeting Ukraine in July (“1”), and there was a particularly large spike in Russian martial activity targeting the United States in September that was not covered in Russian media. Moscow’s reflexive activity, it seems, was designed to change narrative discourse both at home and abroad regarding its posture towards the United States and Ukraine in a manner at odds with broader international coverage. We saw earlier echoes of this in the spring, as Russia’s activity targeting Ukraine was temporarily framed as more legal and economic before the escalation. It appears that in preparation for future military coercion, Russia sought to broaden and demilitarize the scope of its activities toward that actor.

Implications

Russia’s 2022 war in Ukraine serves as a wake-up call to unpack the logic and practice of coercion that failed in the preceding years. Traditional models of bilateral strategic interaction feature reciprocal behavior along a single dimension that does not fully comport with the cross-domain features of contemporary great power confrontation. Moreover, the divergent ways of Western and Russian coercion warrant reconsideration of how decisionmakers tailor effects and signal intentions. Here, the preliminary evidence suggests that while Russia’s approach to reflexive control may purposefully obfuscate the assessment of credibility and resolve, consistency in the messaging to foreign and domestic audiences may signal the escalation from coercion to the use of large-scale force.[2] Thus, while the humanitarian tragedy in Ukraine may seem to render moot issues of coercion, a clearer understanding of the differences between Western and Russian statecraft will enable future efforts to discern and foster the mutual restraint necessary to put guard rails onto the long-term competition that will continue long after the conclusion of this brutal war.

[1] The GDELT Project is one of the largest open-access spatio-temporal datasets in existence, pushing the boundaries of “big data“ study of global human society.

[2] RT and Sputnik are considered Russian media.

Adam Stulberg is Professor and Chair of the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs at the Georgia Institute of Technology. Dennis Murphy is a PhD student at the Georgia Institute of Technology.