Image credit/license

Ukraine’s decentralization reform is considered one of the country’s most successful reforms since the Euromaidan and an essential factor in its resilience to Russian invasion. Instead of local state administrations accountable to the President and the Cabinet of Ministers, the management of hromadas’ resources was transferred to local self-governments accountable to their residents. Not only has this improved public trust in the local authorities, but local governments and local state administrations[1] increasingly treat one another as equal partners, an essential step toward implementing the European Charter of Local Self-Government.

However, Russian aggression and the resulting establishment of martial law have altered the balance. As the powers of military administrations have expanded, experts have noted an increase in tensions between the central government and local self-governments, as well as insufficient involvement of local self-government in discussions of important issues such as the adoption of draft law No. 5655 (urban planning reform) and the redistribution of “military” Personal Income Tax (PIT) from local budgets to the state budget. Yet it is vital to strike a balance between central control intended to increase efficiency in wartime and local self-governance that can quickly mobilize local resources to meet local needs. A transparent dialogue between the various levels of government is a key tool for distributing responsibilities, making decisions, and minimizing conflict. By working together, central government actors, local authorities, and other major stakeholders can help to preserve the gains that have been made by the decentralization reform since 2014.

Status Quo: Military Administrations as New Structures in Local Governance

On February 24, 2022, in response to Russian aggression, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky declared martial law. This granted public authorities, the military command, and local governments all the powers necessary to avert the threat. Temporary state bodies known as military administrations were created in each region and district to ensure the effective exercise of these powers and to repel the enemy (see Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Military administrations at different levels of governance

Source: Darkovich and Hnyda 2023.

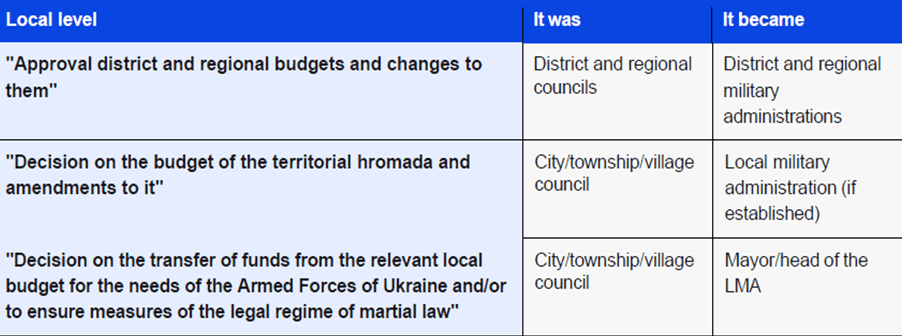

Table 2. Changes to budgetary power under martial law

Source: Darkovich and Hnyda 2023.

Under this decree, the heads of pre-war administrations further acquired the status of heads of military administrations. At district and regional level, this process was automatic. At local level, local military administrations (LMAs)—including military personnel, representatives of law enforcement agencies, members of the civil defense services, and individuals who had concluded an employment contract with regional military administrations or the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine—were formed from scratch, but the current heads of territorial communities could be appointed as the heads of LMAs following security screening.

The declaration of martial law has created a number of policy problems for local-level Ukrainian actors. The variety of approaches to the establishment of LMAs, as well as a lack of legal clarity about when these should be established, has created uncertainty about the future of the existing local authorities. Where military and peacetime authorities exist side by side, the overlap between their roles can lead to further confusion and dissatisfaction among local residents. This overlap is particularly counterproductive in a context of local-level staff shortages and general overload. Finally, state and donor policies have produced an unbalanced distribution of resources particularly detrimental to those hromadas on the frontlines and under occupation. Below, we explore each of these issues in further detail before outlining recommendations for meeting each challenge.

Uncertainty about the Future of Local Authorities

Local military administrations may be established in those settlements where village, town, or city councils and/or their executive bodies are not carrying out the powers vested in them by the Constitution and laws of Ukraine, as well as in “other cases” provided for by this Law.

From a legal standpoint, this wording is less than clear. First, the clause about “other cases” does not refer to specific requirements of the law specifying other grounds for establishing LMAs. Second, the construction “inability to exercise authority” may make the determination of what is a sufficient use of power too discretionary. Indeed, it is unclear whether it is a general inability to exercise authority (i.e., a city council’s inability to function) or the failure to exercise specific powers accorded to local self-government body—many of which are discretionary to begin with, including passing a motion of no confidence in the mayor, uniting in associations, establishing mass media, etc.—that justifies the establishment of an LMA. Third, the law does not indicate which entity is authorized to establish the legal fact of inability to exercise authority (although in general a court, as an independent and impartial body, is responsible for deciding legal facts).

Most often, local military administrations have been created in territories where hostilities are ongoing, those that are temporarily occupied, and those that have been liberated from Russian occupation (see Figure 1). Currently, military administrations are operating in all types of hromadas (urban, village, and settlement—see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Geography of LMAs in Ukraine

Source: Darkovich and Hnyda 2023.

The lion’s share of military administrations have been established in the Kherson (49), Zaporizhzhia (37), Donetsk (36), Luhansk, and Kharkiv (26) regions—that is, in regions relatively close to the frontline. It should be noted that the work of almost half of these military administrations is impossible due to the occupation of settlements. As a result, these LMAs often operate in other cities that are controlled by the Ukrainian government.

Figure 2. Number of LMAs by hromada type

Source: Darkovich and Hnyda 2023.

Different regions have taken different approaches to establishing LMAs. In Kherson region, for example, all local self-government bodies have been replaced by LMAs. By contrast, in the Donetsk, Luhansk, and Zaporizhzhia regions, where the fighting and the level of occupation are the same, some occupied hromadas still have local self-government bodies.

The establishment of LMAs compromises local self-governance. Often, the heads of these administrations are not elected by the hromada they now govern. Consequently, they may lack an understanding of the local context, be devoid of a supportive executive team, and have no experience of governing the hromada. Moreover, LMAs are able to ignore the needs and interests of local governments and exclude them from the process of solving important issues for the hromada, weakening the political leadership of hromadas and diminishing these actors’ interest in active participation in socio-political life. This, in turn, can negatively impact the involvement of stakeholders and local politicians in fundamental political processes.

To address these issues, we make the following recommendations:

- Explicit Rules of Establishment: To reduce the existing heterogeneity of practices for establishing LMAs, the Verkhovna Rada should clearly define and prescribe indicators for assessing the capacity of a local self-government body (LSB) to perform its functions by amending the law.

- Appoint Local Leaders: The President should seek to install locally elected leaders as LMA heads. This would improve representation and help to maintain continuity with the existing self-government of hromadas, including retaining the support of executive teams.

Overlap between LMA and LSB in the Same Hromada

When a municipal military administration is established, the head of the LMA approves its structure and staffing. It is registered as a separate legal entity and budget management body from the existing mode of local self-government. The military administration exercises power for the duration of martial law and 30 days after the termination thereof.

However, part II of Article 10 of the Law “On the Legal Regime of Martial Law” allows the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, upon the proposal of the President, to authorize the head of the military administration, in addition to the powers conferred on the LMA, to exercise the powers of the elected self-government’s executive committee and the mayor. In other words, there are two formats for the functioning of LMAs (see Table 3).

Table 3. Formats of LMAs

Source: Darkovich and Hnyda 2023.

In situations where not all functions of the LSB have been transferred to the LMA, the two bodies operate simultaneously in the same hromada. This creates uncertainty among residents as to who is responsible for different functions. In some cases, this has resulted in residents of the hromada blaming LSBs for policies that are outside the competence of local self-government.

To address these issues, we make the following recommendation:

- Enhance Citizen Communication: LMAs should implement robust communication strategies to inform citizens about changes to local self-government and the responsibilities of LMAs and LSBs going forward. This would ensure transparency and help citizens understand the roles of each institution.

Decline in Influence of Self-Governance on Regional and National Processes

Among our respondents, leaders of border and occupied hromadas indicated that their connections to—and collaboration with—the regional and district administrations had declined since the declaration of martial law. Communication has become more formal, with local leaders now receiving less information about project and grant participation possibilities and government financial programs from the regional and district authorities, which are the entities that meet regularly with donors and humanitarian assistance programs.

The “military” PIT discussion in November 2023 and the repeated postponement of a vote on the legislation necessary to support the military from the local budget, which was demanded from LSBs by activists and citizens, show that communication between the central government and hromada leaders is also far from perfect. Many hromadas perceive their reduced influence as a threat to a fair recovery process, fearing that party affiliations and nepotism at the regional level will influence the distribution of funding and jeopardize the recovery of individual hromadas.

To address these issues, we make the following recommendations:

- Engage with Regional Associations: A new tool for hromada representatives to interact with the central government, the Congress of Local and Regional Councils under the President of Ukraine, has been created, but some hromadas are not ready to discuss their problems in this format. Therefore, regional (oblast) military administrations and donors should also engage with regional offices of hromada associations, where a select group of hromada leaders provide information about problems and challenges facing hromadas.

- Create New Recovery and Development Offices: International partners’ resources can be used to develop a platform for interaction between hromadas and regional authorities. For instance, at the regional and hromada levels, Recovery and Development Offices have been created in cooperation with such international partners as the European Union, the Government of Sweden, and the United Nations Development Program.

Duplication of Functions in a Context of Local-Level Staff Shortages and General Overload

All hromadas are facing issues with staff shortages when it comes to conducting data collection for and answering requests from the regional and district military administrations. These difficulties are most apparent in the temporarily occupied hromadas (whose LMAs are in exile) and frontline hromadas, as many employees have left and the security situation, combined with a lack of funding, makes it hard to attract qualified specialists from further afield. Staff shortages have also compromised hromadas’ ability to work with donors and raise funds, as such efforts require both time and qualified specialists (preferably with English language skills). As a result, the hromadas that would benefit the most from donor assistance are also the least able to access that assistance. Finally, the vast number of requests for information submitted by DMAs and RMAs mean that the head of the hromada often requires multiple staff members to handle them, even though DMA and RMA requests are often identical.

To address these issues, we make the following recommendations:

- Establish Programs of Financial Support for LSBs and LMAs in Frontline Regions: Donors and state institutions should develop financial support programs that would include financial incentives for staff to take jobs in these high-risk conditions. Without such incentives, the acute staff shortages will render the effective functioning of local institutions impossible.

- Streamline RMA and DMA Functions: Region and district administrations need to review and harmonize the reporting and data requirements for LSBs and LMAs to reduce duplication of requests and functions. Introducing automated data collection systems would further enhance the efficiency and accuracy of reporting.

- Share Regional Experience: To improve communication and scale up successful practices between regional actors, employees of RMA economic development departments, regional development agencies, and regional offices for international cooperation should share their experiences with common problems. This should not be confined to meetings, but should also include summarizing successful practices/projects.

Unbalanced Resource Distribution

Temporarily occupied and frontline hromadas tend to receive fewer material resources than their counterparts further from the frontline. Donors often restrict their participation in recovery efforts and projects. Accordingly, some hromadas indicate that the current assistance from donors and the state is insufficient to support critical recovery needs, including materials and tools. Urban hromadas have done better at overcoming these challenges with resource allocation, as their leaders have often managed to develop personal connections with municipalities abroad and forge partnerships that have come with financial and practical support.

To address these issues, we make the following recommendation:

- Revise Donor Priority Policies: Donors should eliminate restrictions on the participation of frontline and border hromadas in projects important to maintaining the functioning of territorial communities. As the SeeD report “IMPACT OF WAR: Front Line Communities and Resilience” shows, the main priorities for these hromadas are their health, education, transport, and energy systems. Without special support from the state and donors, frontline territories will be unable to ensure the normal functioning of their communities, which will lead to complete depopulation.

The Alternative: Risk of Recentralization

In the absence of policy reforms, there is a risk of recentralization should the armed conflict persist. Not only may the state want to centralize resources to fight the enemy, but actors opposed to decentralization may seek to exploit the imposition of martial law as a pretext to return to the status quo ante (as described by the theory of “stubborn structures.”) Decentralization, the first phase of which ended only in 2020 with the adoption of a new administrative division and new economic opportunities for hromadas, may now be very sensitive to the attempts of “stubborn structures” to take advantage of martial law.

These challenges are not unique to Ukraine. Instead, they are rooted in the communist legacy of centralized and hierarchical governance. As Regulska describes in the case of Poland, post-communist leaders inherited highly centralized, overly bureaucratic, and cumbersome state structures. In the previous system, both political and economic decisions had been made exclusively in the upper echelons of the party-state apparatus through a paradoxical process of “democratic centralism.” Lower levels of the party-state apparatus, for their part, merely implemented these decisions.

In Ukraine, a centralized decision-making system existed at the subnational and local levels for more than 20 years before the decentralization reform began in 2014, making it difficult to break down existing “stubborn” structures and governance models.[2] Thus, there is now a very real risk of recentralization due to both “stubborn structures” and because the state might seek to increase centralization for the sake of efficiency.

Martial law and war present significant challenges for both local military administrations (LMAs) and local self-government bodies (LSBs). To sustain the success of decentralization reform in Ukraine, it is imperative to address these policy issues. By doing so, we can help preserve the integrity and functionality of Ukraine’s decentralized governance. Failure to do so, meanwhile, risks reverting to centralization or collapsing the decentralized system due to war-induced pressures and structural challenges.

*****

This memo is based on the Center for Sociological Research Decentralization and Regional Development Report “(De)Centralisation? Trends in the Interaction of Local Self-Government and State Authorities” and uses materials from the academic article co-authored by M. Rabynovych, T. Brik, A. Darkovich, M. Savisko, and V. Hatsko, “Ukrainian Decentralisation Under Martial Law: Challenges for Regional and Local Self-Governance,” which is currently under consideration for publication in a special issue of Post-Soviet Affairs.

Andrii Darkovich is a Researcher at the Center for Sociological Research, Decentralization and Regional Development at the KSE Institute.

Myroslava Savisko is Project Manager of the Center for Sociological Research, Decentralization, and Regional Development at the KSE Institute and a Erasmus Mundus Scholar.

[1] A Local State Administration is a subnational governmental institution at the oblast (regional) level, appointed by and accountable to the Central Government and President, whereas Local Self-Governments are elected by residents and accountable to them.

[2] This is our own argument based on Magyar 2019 and Minakov 2019.

Image credit/license