The implications of the Russian invasion of Ukraine will affect global security architecture for decades to come as Moscow continues to escalate the conflict. Meanwhile, countries located in the EU’s eastern neighborhood confront strategic dilemmas. As a frontline state in the “gray zone,” outside the safety of NATO’s security umbrella, Georgia faces the daunting tasks of pursuing Euro-Atlantic integration, strengthening its democratic resilience, preserving sovereignty, and avoiding Russian aggression at the same time.

Despite the show of Western resolve over Ukraine, officials in Tbilisi are forced to walk a thin line between being sensitive to Russian interests while not alienating the West. Georgia’s allies in the United States and Europe were surprised by Tbilisi’s rather passive foreign policy after the Russian invasion, especially considering that Moscow had demanded that NATO close the door on Georgia’s future membership as well as Ukraine’s. Georgia remains committed to its Euro-Atlantic aspirations, even formally applying for EU membership this year, although relations with its Western partners are cooling. This, along with its ambivalent position over the war in Ukraine, raises the question of whether the Georgian government is heading toward self-imposed Finlandization.

Tbilisi: Cautious or Accommodating?

The invasion of Ukraine illustrated that the Russian Federation is willing to use direct military aggression against its neighbors in order to restore its hegemony in the region. The Kremlin’s revisionist politics have a significant impact on regional security as well as Georgia’s vital national interests. In the early days of the Russia-Ukraine war, the reaction from the Georgian government was extremely cautious and self-restrained. It refused to join any Western sanctions against Moscow, dismissing them as unproductive. Despite voting against Russia in the United Nations General Assembly and the Council of Europe, it exercised diplomatic self-constraint. The reaction amounted to mild appeasement of Russia and deepened Georgia’s estrangement from the West.

It is puzzling why Georgian authorities, instead of actively working with Western partners not to get stuck on the wrong side of the new Iron Curtain, are self-imposing low-key foreign policy in this era of major geopolitical shifts. The impression that the Georgian government is seeking to improve relations with Moscow while being much more committed to solidarity with Ukraine is amplified by the presence of Russian troops in South Ossetia and Abkhazia. As they represent a constant threat to Georgia, Tbilisi tries to maintain a low profile in international politics and stay off of Russia’s radar. Several analysts even raised concerns about whether some of the Georgian government’s actions correspond to the “sincerity of the country’s Western aspirations.”

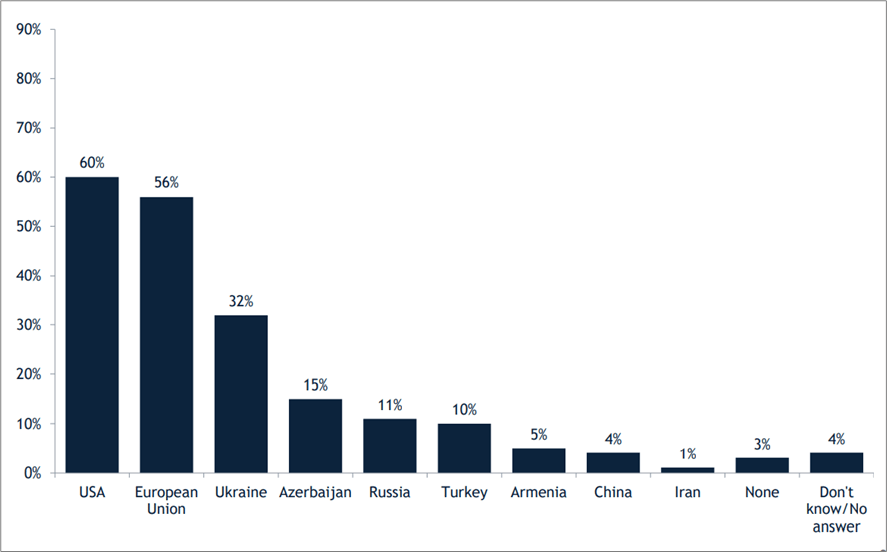

Another worrisome fact was that, unlike previous years, the Georgian Parliament failed to secure opposition support for a resolution passed in support of Ukraine. The ruling Georgian Dream (GD) party single-handedly passed a resolution that did not even mention Russia and was referred to as a “blank piece of paper” by a Western observer. It seems that narrowly defined national interests based on party interests and short-term political gains threaten the standing consensus on foreign policy, making its key focus rather vague and creating strategic ambiguity. This positioning of decision-makers in Tbilisi also goes against the wishes of the absolute majority of Georgians, as 96 percent of those polled think that the war concerns Georgians as well, and 86 percent think it is their war too. It also needs to be noted that after the United States and EU, Ukraine is perceived by the Georgian population as its main political ally (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Georgia’s Most Important Political Partners (June 2021)

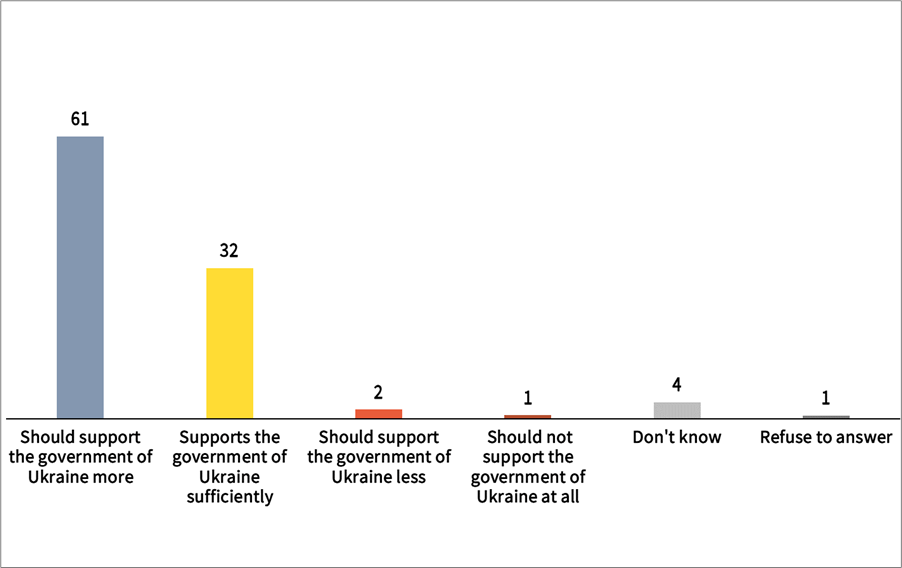

Additionally, a recent opinion poll suggests 61 percent of Georgians think that their government should do more to support Ukraine (Figure 2), and 66 percent that Georgia should join all or at least some of the established sanctions on Russia. Strong support for Ukraine’s cause among Georgians is also illustrated by the existence of the Georgian National Legion, comprised of volunteers fighting in the war zone.

Figure 2. Opinion of the Government of Georgia in Relation to the Government of Ukraine (Percent; March 2022)

In this context, it seems counterintuitive that the Georgian government moves even further from its Western strategic partners instead of more active involvement to defend the national agenda on the international level. The government appears committed to a long-term political crisis, in parallel with democratic backsliding and troubling relations with the West. Moreover, the government’s passive stance in international affairs significantly increases the risks of the country’s irrelevance on the global political agenda as well as its gradual isolation. If Russia manages to achieve its geopolitical goal—ending NATO’s open-door policy—the government’s behavior would directly affect Georgia’s foreign policy and security.

Pragmatic Policy or Russian Informal Veto Over Foreign Policy

These puzzling developments in Georgian foreign policy can be attributed to the “normalization” toward Russia that started in 2012. Unlike the previous United National Movement (UNM) government, which used harsh rhetoric toward the Kremlin and continuously focused on the threats coming from Georgia’s northern neighbor, the Georgian Dream government chose a more “pragmatic” approach toward Moscow. The essence of the ruling party’s policy is to avoid irritating the Kremlin and to maintain Euro-Atlantic aspirations while also trying to restore and strengthen economic, humanitarian, and trade links with Russia. This policy also aims to reduce antagonism between the West and the Kremlin when it comes to Georgia’s foreign policy. In recent weeks this (foreign policy) strategy went as far as accusing the Georgian president of breaching the constitution by her unauthorized visit to France.

Nevertheless, the GD’s foreign policy cannot be explained solely by external factors; internal political factors should also be considered. The change in rhetoric was important for the post-2012 ruling party to establish its political identity and distance itself from the previous government. As a result of this “pragmatic”approach, there was a noticeable increase in humanitarian and economic links between Georgia and Russia, especially in the tourism sector. Over the last few years, there is also a stable growth in Georgia’s trade with Russia, including electricity imports and money transfers, which intensifies anxiety in Georgian society over growing dependence on Russia. Georgians are unsure how this policy serves Georgia’s security interests, although there is a strong awareness that increased economic dependency on Russia makes the country more vulnerable to Kremlin blackmail. Moreover, amid heavy economic sanctions and clampdowns on dissent, Russian citizens are massively fleeing their country, including to Georgia (visa-free for one year), which has increased concerns among Georgians over a variety of possible implications.

The GD’s “appeasement” policy toward Russia could also be based on certain calculations that NATO would not be ready to militarily support Georgia in an armed conflict with Russia. President Zelensky’s harsh criticism of NATO over not establishing a no-fly zone in Ukraine might support this argument, which is important for the ruling party to shore up its domestic support. GD representatives often highlight that the party’s strategic governance managed to prevent adventurous politics against Russia, reducing the chance of future threats, as Georgia’s Western partners are not ready to militarily support the country against Russian aggression. The Georgian government’s position is further supported by the U.S. president’s stance in the wake of the ongoing crisis, stating that the United States is not considering sending its troops to Ukraine.

Is Georgian Foreign Policy Consistent?

These developments raise questions about the Georgian government’s decision to adhere to its pragmatic foreign policy. Although NATO and the United States might not consider direct military confrontation with Moscow over Georgia and Ukraine at this point, Tbilisi does not have any other security alternatives unless it reconsiders its foreign policy course. “Westward” is the only option for Georgia to maintain sovereignty and independence in the face of its aggressive northern neighbor.

The government’s policy creates the impression that under “normalization” politics, Tbilisi’s self-imposed restrictions would outweigh the benefits it would potentially receive under a more active “value-based” foreign policy. That impression is further strengthened by the fact that despite Georgia’s pragmatic politics, the Russian government has repeatedly halted direct flights to Tbilisi over the Russophobia argument, continued borderization along the administration lines of occupied regions, and done nothing to resolve the conflicts over Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

Simultaneously, Russian authorities are taking steps that might indicate their readiness to give “carrots” to Tbilisi in exchange for a “pragmatic” foreign policy (not joining sanctions, not providing assistance to Georgian volunteers, and forbidding entry to Georgia for some Russian opposition figures). To be more exact, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs made it clear that it was expecting “balanced” politics from Georgia. In parallel with its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian authorities opened the market for 15 Georgian and one Azerbaijani dairy companies, possibly as a reward for Tbilisi’s relatively neutral position in the conflict. It seems that by portraying Georgia as a situational ally, Moscow is trying to sow discord between Georgia and its strategic partners as this decision has political, not economic calculations.

These steps obviously go beyond the GD’s “normalization” politics. In addition to these developments, the Kremlin’s decision not to include Georgia in the list of unfriendly countries raises reasonable concerns in Georgia that Russia may already perceive the country as being under its indirect influence and hold an informal veto over Tbilisi’s foreign policy decision-making. If this is the case, regardless of whether President Vladimir Putin succeeds or fails in his bloody campaign in Ukraine, the Georgian government will face a strategic dilemma: give up its Euro-Atlantic course and exist with limited sovereignty and all the negative consequences that entails or face a military confrontation with Russia.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that there are no formal talks on Georgia’s Finlandization, the ruling party’s strategy, which focuses on very cautious and “pragmatic”foreign policy decisions, poses certain risks for the country’s Euro-Atlantic foreign policy choice. Those risks are further exacerbated by internal political crises, strengthened anti-Western political groups, and unstable relations with the West.

Inconsistency in Georgian foreign policy raises questions for the country’s strategic partners and gives Moscow hope since the neutrality of Georgia, as well as other Eastern Partnership countries, is an acceptable scenario for Russia. However, taking into consideration the Kremlin’s rhetoric toward Ukraine, one should assume that Moscow perceives Finlandization as a temporary step toward the gradual inclusion of Eastern Partnership countries in Russian-dominated organizations like the Eurasian Union, CSTO, etc. There is very little chance that Russia—a superior military power operating within its sphere of influence—is going to respect its neighbors’ neutrality.

Hence, the future status of Ukraine is a problem for Kyiv and Tbilisi. If Russia manages to acquire an informal veto over NATO’s open-door policy and halt eastern enlargement perspectives, it will lead to Georgia’s regional and international isolation. It is crucial for Georgia to be as active as possible in the international arena and actively engage in different strategic formats that ensure Western involvement in regional security. This is more important now as a consolidated West is united against Russian aggression, which creates momentum for the Eastern Partnership countries, including Georgia, to finally acquire an EU membership perspective.

Regardless of the war’s final outcome, its consequences will have a significant effect on regional and Black Sea security for decades to come. The Georgian government’s policy of accommodating Russia will be difficult to sustain—as well as dangerous to Georgian sovereignty—when the West and Russia are locked in a major conflict over Moscow’s unprovoked aggression against Ukraine. Tbilisi’s position confuses its Western partners, alienates its closest allies (including Ukraine), and strengthens Russia’s perception of Georgia deliberately returning to Russia’s sphere of influence. If the Georgian government does not adapt to changing circumstances, it will risk being isolated internationally and left alone with Russia.

Kornely Kakachia is Professor of Political Science at Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University and Director of the Tbilisi Georgian Institute of Politics. Shota Kakabadze is a Junior Policy Analyst at the Tbilisi Georgian Institute of Politics. This memo is based on a more detailed study coauthored by Kakachia and Kakabadze, “Creeping Finlandization or prudent foreign policy: Georgia’s strategic dilemmas amid the Ukraine crisis,” Tbilisi Georgian Institute of Politics, February 2022, published in Georgian.