The coronavirus pandemic in Russia posed the same myriad challenges as in many countries: a devastating loss of life, strained healthcare resources, and an economic crisis. In Russia’s case, the pandemic also came at a politically sensitive time during which the country voted on and passed a constitutional referendum. After initially banning foreigners from China and emphasizing the disease as a foreign threat in February 2020, the regions of Russia had adopted strict lockdowns, including digital pass systems, by late March and early April. Lockdown, however, did not last long. The government rapidly reversed course in June, opening up the country and making big vaccine promises in the lead-up to the referendum overhauling the constitution in July. Ultimately, the Russian response was an uncoordinated plan that devolved into a minimalist approach pinning its main hopes on a vaccine rollout. Outside observers and Russians alike are skeptical about the accuracy of official COVID-19 numbers, but even the official numbers have not been reassuring.

This memo addresses three important questions about COVID-19 in Russia: what Russians expect from the government, what they have gotten, and what they think about it. Russian public opinion combines low expectations, concern, skepticism, and acceptance. Surveys conducted in 2020 reveal that expectations for government-provided healthcare were already low. The government’s pandemic response was inconsistent and has relied heavily on a vaccine over prevention. The Russian public is concerned about COVID-19 and questions official numbers, but many still approve of the leaders’ response. In short, the Russian public as a whole is more or less satisfied with the government’s efforts. Despite a bungled response, there is little evidence that the pandemic crisis itself will significantly undermine support for Putin, United Russia, or the current regime.

What Do Russians Expect from the Government?

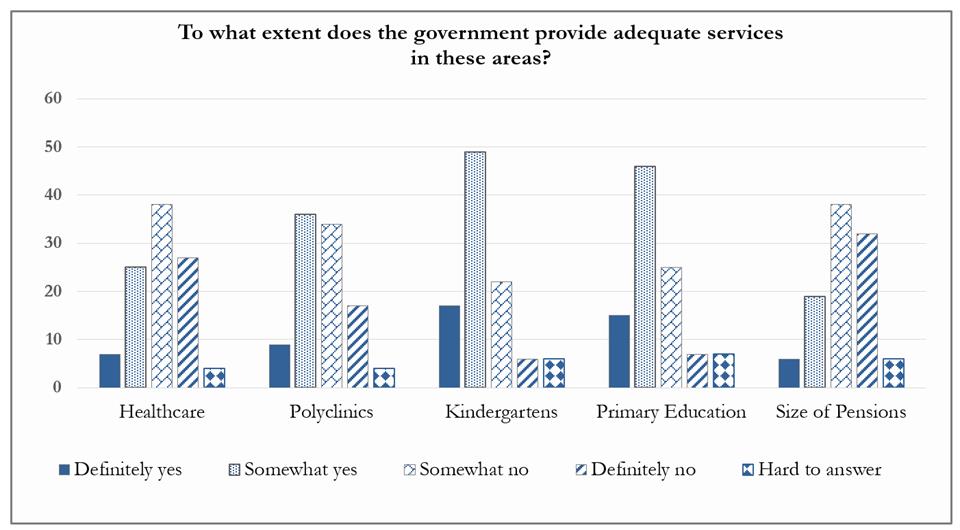

Survey data from February 2020 give us a better idea of what Russians expected the government to provide regarding social services right as the pandemic was beginning.[1] At the time of writing in January 2021, it appears that Russians did not expect very much, and their expectations were met. Figure 1 below shows the results of a question asking respondents to evaluate to what extent the Russian government provided adequate services in five different areas: healthcare, polyclinics, kindergartens, primary education, and the size of pensions. The possible responses included definitely yes, somewhat yes, definitely no, somewhat no, and hard to answer.

In relation to understanding public reactions to the government’s response to COVID-19, healthcare is one of the important dimensions. In the survey, the distinction between healthcare writ large and polyclinics is significant. The healthcare system includes hospitals and the system as a whole. Polyclinics are the primary care providers for most day-to-day healthcare provision. Furthermore, we can see that the responses differ for healthcare as a whole compared to the system of polyclinics, with the latter being evaluated somewhat more positively. For both healthcare and polyclinics, less than 10 percent of respondents said that the government definitely provides adequate care, reflecting a pervasive opinion that these services could be much better. About 25 percent of respondents thought that government-provided healthcare was somewhat adequate compared to 35 percent who thought polyclinic care was somewhat adequate.

Figure 1

Notably, the vast majority of Russians (68 percent) do not think that government-provided healthcare is adequate. Just under half of the respondents evaluate polyclinics as somewhat or definitely inadequate. By comparison, Russians are much more positive in their assessments of government-provided kindergartens and primary education. Even pension provision—an often contentious and hotly contested issue in Russia—is ranked more positively than government-provided healthcare.

What do healthcare expectations mean for how Russians might react to COVID-19 policies? Although speculative, there are two possibilities that stand out. First, low evaluations of government-provided healthcare could mean that Russians are primed to negatively assess the government’s response to the pandemic. Alternately, it may be that a low bar is easier to meet. If the Russian government’s response to COVID-19 outstrips low expectations, then Russians might be primed to be either positive or at least accepting of the government’s response.

Certainly, many governments around the world could have done better in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Russian response was not as strict or consistent as some of its European counterparts, but Russia also faces unique challenges in having a much larger population spread out over a federal system with a huge urban-rural divide in administrative capacity, socioeconomic conditions, and the quality of healthcare. Unsurprisingly, there is a great deal of regional variation in how well the pandemic has been managed. This raises important questions about what the government was able to do and how its citizens evaluated its response.

What Did Russians Get?

The Russian government provided a mixed response that has come recently to rely on promises of mass vaccination. Marlene Laruelle and Madeline McCann identified an early post-Soviet model of COVID-19 response, which relied on downplaying the threat. It is likely that this was at least in part a strategic decision based on the very real limitations of state capacity in some post-Soviet states like Russia and Belarus. Because officials were aware of the state’s very serious and real limitations in being able to respond to a health crisis, they opted instead to tell the public that the threat of COVID-19 was low.

Russia, like some other countries, followed four stages in its COVID-19 response in 2020.

Phase 1: downplaying and xenophobia. From February to mid-March 2020, the Russian government focused on COVID-19 as a foreign threat. Russian police and citizens harassed Asians in the country, and military transports from Russia to China were restricted. In February 2020, the government began restricting the entry of foreigners from China into Russia but also announced five vaccine prototypes. Even in early March, Putin was downplaying the threat, claiming false news reports were being distributed in Russia to incite panic. In March, the government announced a “non-working period” and the closure of some public places and buildings.

Phase 2: lockdown in some regions. In mid to late March, it quickly became apparent that COVID-19 was indeed a serious threat, and infections were rapidly rising, especially in urban areas. In April, 21 regions of Russia, including Moscow, introduced a digital pass system. Moscow instituted checkpoints to enforce the digital pass system. The municipality announced the building of temporary hospitals to treat COVID-19 patients.

Phase 3: reopening and vaccine promises. Beginning in June, Russian leadership quickly pivoted to reopening and promising a vaccine. This was an abrupt change from previous announcements by Moscow mayor Sergei Sobianin that lockdown would last until a vaccine was available.

Phase 4: second wave and vaccine rollout. An abrupt increase in infections was apparent beginning in September 2020. Schools in Moscow were shut down again, and COVID-19 infection numbers continued to rise through the fall and winter of 2020. The daily number of new infections being reported by The Moscow Times peaked on December 26, but thousands of new cases were being reported every day through January. The Sputnik-V vaccine is now being administered and bought by other countries but is in short supply in many Russian regions.

Many countries followed some variant of these 4 phases. The distinctive features of the Russian response were the early reopening in summer and the very early promises about the Sputnik-V vaccine. Ultimately, Russia does not appear to be rolling out its vaccine significantly earlier than other countries, but it was among the first to promise that the vaccine was coming. This reflects the government’s emphasis on the vaccine and not preventing the spread of infections. In all likelihood, the government chose this path as a strategic choice. The high inequality of care between urban and rural areas, the federal nature of Russian governance, and the variable administrative capacity of regions made it unlikely that Russia could enact and enforce a nationwide lockdown. Given this, the government did not even attempt a more coordinated response. This also meant, of course, that the Russian government accepted that many Russians would die before the vaccine could be developed, produced, and administered.

What Do Russians Think About It?

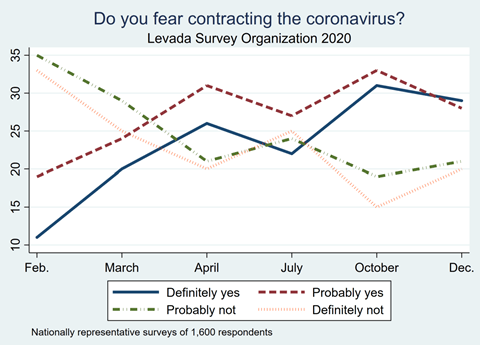

There is no major public backlash to the government’s handling of the COVID-19 crisis. Indeed, the only protests about the government’s handling of the pandemic have been a few anti-vaccine protests backed by the Communist Party in Moscow. Figure 2 shows the results of surveys taken throughout 2020 asking whether respondents fear contracting the coronavirus. In December 2020, the percentage of Russians who definitely or probably feared contracting the coronavirus was at nearly 60 percent, which is as high as it was in April. There is a notable dip in concern about contracting coronavirus in July when infection rates had declined.

In spring 2020, only 16 percent of Russians fully trusted official information about the coronavirus situation in Russia, while 38 percent somewhat trusted official information. More than a quarter of the population reported that they absolutely did not trust the official information. Despite the government’s reliance on a vaccine strategy, vaccine skepticism is also high. Surveys conducted by Levada from August to December 2020 indicate that 36-38 percent of Russians are willing to get the vaccine and roughly 60 percent are not.

Figure 2

Despite a fear of contracting the coronavirus and significant skepticism about official information, about 60 percent of Russians somewhat or completely approve of how regional leaders addressed COVID-19 in October 2020. This is the same approval rating of regional leaders’ responses that Russians gave in May, although many more respondents now say they somewhat approve of regional responses instead of completely approving. Approval of Putin’s handling of coronavirus in May was similarly high, with 60 percent of respondents completely or somewhat approving.

Furthermore, even in April 2020, many Russians were not working at home. Only 8 percent reported working at home more, 13 percent reported being fully remote, and 8 percent reported that they were on obligatory leave with pay. By July after the reopening, only 7 percent reported working at home more, 5 percent were fully remote, and less than 1 percent were on leave with pay.

Before the pandemic hit Russia in earnest, Russians were giving largely negative assessments of government-run healthcare. An important remaining question is if Russians are concerned and skeptical about the present situation, who do they hold responsible? And what are their expectations about what the government can actually provide versus what the government would ideally provide?

Conclusions and Looking Ahead

Much depends on how extensively and how quickly the Russian public will be vaccinated. The Kremlin has touted the Sputnik-V vaccine as among the best in the world. Recently, private clinics in Moscow attempted to get permission to administer the Pfizer and Modern vaccines before they were officially approved but were denied. Schools reopened for all schoolchildren on January 25, despite the still high number of daily infections being reported and the fact that the majority of teachers have not been vaccinated.

Before the onset, the Russian public’s expectations for the government’s response to a pandemic were primed to be low, and the government has largely met that low standard. Nonetheless, the ongoing loss of lives and economic devastation has been stoking some discontent with the government. As many countries struggle to address the pandemic, it may be likely, however, that Russians will come to blame the pandemic’s consequences not on leaders but bad luck. With the government’s response in keeping with general public expectation, major dissatisfactions far have not been provoked, and the pandemic crisis itself has not been significantly undermining support for the regime.

[1] This is an original survey question included on a survey conducted by the Levada Survey Organization in February 2020. Data are available upon request.