(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) On April 1, 2021, an Antonov AN-124 Russian aircraft landed in New York City’s JFK airport with cargo of personal protective gear and medical equipment. The Kremlin’s social media accounts went into overdrive, publicizing the shipment as Moscow’s “humanitarian gesture” using the hashtag #RussiaHelps. The U.S. government countered the narrative insisting that Washington had paid for the medical supplies. A week earlier, several Russian IL-76 military planes delivered medical equipment, pharmaceuticals, and epidemiologists to COVID-19-stricken regions of Italy in a humanitarian operation dubbed “From Russia with Love.” After Italy came Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and three dozen other countries, which received bilateral COVID-19 aid from Russia between March and December of 2020. International reactions to Russia’s humanitarian assistance have been mixed. Many Western countries accused Moscow of taking advantage of the pandemic to promote an image of Russia as a responsible international player. The Russian government has portrayed its assistance as acts of generosity to help countries suffering the consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak.

An analysis of Russia’s COVID-19 aid reveals several motivations for Moscow’s humanitarian largesse. While some of Russia’s aid has been tied to humanitarian objectives, it has also been an integral part of Moscow’s strategy for projecting power on the global stage and supporting diverse political objectives. Moscow’s use of humanitarian aid for geopolitical benefits, however, has not always translated into increased diplomatic or soft power influence. Neither has it played a critical disruptive role in the humanitarian system by itself. Nevertheless, jointly with the humanitarian activities of China that has used humanitarian aid as a foreign policy tool and prioritized bilateral and opaque mechanisms of state-to-state funding, Russia’s approaches to humanitarianism can undermine the basic principles of the international humanitarian system. These principles include humanity, neutrality, impartiality, transparency, accountability, and independence.

Russia’s Resurgence in the Humanitarian Field

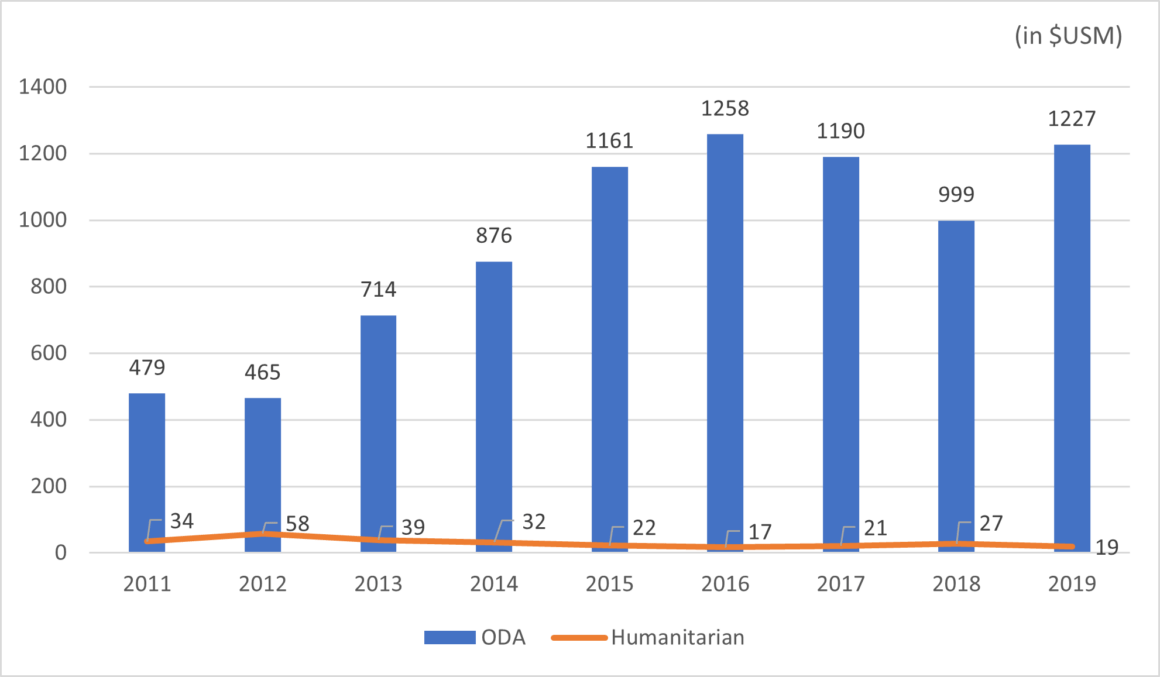

The Russian Federation is not a newcomer in the field of humanitarian assistance. The history of Russia’s aid programs goes back to the post-World War II period when the Soviet regime invested lavishly in various infrastructure projects in South Asia and the Middle East. Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, Russia curtailed its aid activities and became one of the major recipients of development and humanitarian assistance. The rapid growth of petroleum prices in the 2000s spurred economic growth in Russia that was able to free it from external financial dependence. Moscow once again became an international donor as its levels of official development assistance (ODA) nearly tripled between 2011 and 2016 (from $479 million in 2011 to $1,258 billion in 2016) according to the OECD (see Figure 1).

Between 2015 and 2020, humanitarian assistance accounted for about two percent of Russia’s overall aid and averaged about 0.002 percent of Russia’s GDP. In addition to bilateral assistance and humanitarian contributions to international agencies, such as the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Russia has provided support to various non-state associations, such as the Russian-Serbian Humanitarian Center in Serbia and the Switzerland-based International Civil Defense Organization.

The former republics of the Soviet Union have traditionally received most of Russia’s humanitarian assistance. However, the three largest recipients of Russian aid assistance since 2015 have been Syria, North Korea, and Palestine. The bulk of the remaining aid has gone to select countries experiencing humanitarian emergencies in the Middle East (Yemen, Lebanon), South Asia (Afghanistan), and Africa (Guinea, Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo), where Russia’s humanitarian engagement has increased in the last decade. Food security, health, and education have been the three main sectors of Russian humanitarian assistance, with the World Food Organization and World Health Organization being the top recipients of Russia’s multilateral humanitarian aid.

Figure 1: Russia’s Official Development (ODA) and Humanitarian Assistance

When the COVID-19 pandemic spread around the world, Russia began sending coronavirus test kits, masks, protective gear, ventilators, and medical personnel to virus-hit countries. Between March and December 2020, Moscow distributed COVID-19 assistance to nearly 40 countries in all parts of the world as well as to Abkhazia, South Ossetia, the occupied territories of eastern Ukraine, and Palestine. While all Russian neighbors tied to Moscow through membership in the Kremlin-led regional organizations received different volumes of medical supplies and other types of COVID-19 assistance, the bulk of the aid went to Italy, Serbia, China, Iran, Venezuela, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Syria.

In April 2020, the Russian Foreign Ministry announced that multiple African countries had requested Moscow’s assistance in the fight against COVID-19. Weeks later, Moscow had yet to provide such assistance, in stark contrast to China’s prompt deliveries of large consignments of medical supplies and equipment. In subsequent months, the Russian authorities announced COVID-19 aid disbursement to Algeria, Guinea, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Namibia, the South African Republic, and other countries, mostly in the form of coronavirus test kits produced by “Vector,” a state-run virus and biotechnology research center, and personal protective equipment. A handful of countries received ventilators and mobile medical clinics as well as Russian medical personnel sent to assist with the treatment of sick patients.

Russia’s COVID-19 aid allocations have led many experts to conclude that Moscow was strategically choosing its coronavirus aid destinations. In response, the Russian government and commentators accused the West of the relentless practice of demonizing Moscow and underscored the largely humanitarian intent for its coronavirus aid.

Mixing Humanitarianism with Geopolitical Considerations

Russia’s aid allocations have long reflected a mix of humanitarian and geopolitical motives. Both its first-ever concept on development assistance adopted in 2007 and the current concept on state policy in the area of international development assistance approved in 2014 link two of the nine goals of aid to humanitarian and developmental needs, such as poverty elimination and responding to humanitarian disasters. The other goals carry on with the Soviet legacy of using aid to influence global processes, strengthen Russia’s positive image, and facilitate economic cooperation and integration processes with neighbors.

Moscow’s COVID-19 aid distribution decisions continue with the trend. On the one hand, the majority of Russia’s aid has been sent to countries suffering from the COVID-19 pandemic’s rising death toll , as well as to countries with lower levels of development that limit their capacity to respond to the spread of infectious disease. The countries in Russia’s proximity and the members of Russia-led organizations were also consistently among the recipients of its COVID-19 assistance.

However, in the Soviet tradition of “aid for votes,” Russia has used aid to reward countries that have expressed support for its foreign policy priorities by siding with Moscow in the United Nations’ roll call votes. Russia has sent aid to most of the countries that voted against or abstained from voting on United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/262 adopted on March 27, 2014, in response to the Russian annexation of Crimea. This non-binding resolution called on states to steer clear of recognizing a change in the status of the Crimea region. It affirmed the territorial integrity of Ukraine and invalidated the 2014 Crimean referendum. On December 9, 2019, the United Nations General Assembly additionally adopted Resolution A/74/PV.41, condemning Russia’s temporary occupation and militarization of the Crimean Peninsula. Most of the countries that voted against the resolution and many among those that abstained from voting became the recipients of Russia’s COVID-19 assistance in 2020 (see Table 1).

Several other trends in Russia’s COVID-19 aid are further indicative of its non-humanitarian priorities for aid allocation. First, Russia has long viewed its international arms sales as key to its image as a world power and an essential conduit to its influence in global affairs. Aside from oil and gas exports, Russia’s main export commodity has been its advanced conventional weapons. Western sanctions have curtailed Russia’s arms sales by 22 percent in 2016-2020, and Moscow has sought to grow its global arms market in Africa and Southeast Asia. Since 2017, for example, the country has brokered military cooperation deals with more than 20 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Many of these countries, as well as those with long-term partnerships built on arms sales and commercial agreements (Algeria, Central African Republic, Egypt, Guinea, Morocco, etc.), received Russian humanitarian aid.

Table 1: United Nations Voting Patterns and Russia’s COVID-19 Aid

| “Against” UN GA RES 68/262 | Aid Recipient | “Against” UN GA RES A/74/PV.41 | Aid Recipient |

| Armenia | X | Armenia | X |

| Belarus | X | Belarus | X |

| Bolivia | Burundi | X | |

| Cambodia | X | ||

| China | X | ||

| Cuba | X | Cuba | X |

| North Korea | X | North Korea | X |

| Iran | X | ||

| Kyrgyzstan | X | ||

| Laos | |||

| Myanmar | |||

| Nicaragua | X | Nicaragua | X |

| Philippines | |||

| Serbia | X | ||

| Sudan | X | Sudan | X |

| Syria | X | Syria | X |

| Venezuela | X | Venezuela | X |

| Zimbabwe | X | Zimbabwe | X |

Second, Russia’s COVID-19 aid has trailed its oil and gas, transportation, and mineral extraction contracts. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, for example, humanitarian aid and cultural ties have been deployed in support of Russia’s advances in lucrative energy, transportation, and mineral extraction projects. Guinea has been rewarded with a sizable packet of COVID-19 aid due to the profitable economic ties between Russian aluminum magnates and former Guinean President Alpha Conde, who was deposed in a September 2021 military coup. Two other recipients of Russia’s COVID-19 aid, Angola and Zimbabwe, have allowed Russian companies access to the mining of cotton, cobalt, gold, diamonds, and other resources.

A correlation between the presence of Russia’s private military companies (PMC) and aid is another noticeable trend in Moscow’s COVID-19 aid allocations. Russia’s mercenaries have been active in Libya, Syria, the Central African Republic, Mozambique, and Sudan. In several of these countries, Russian security contractors have been seen delivering personal protective equipment, test kits, and ventilators in a public relations stunt designed to clean the tarnished image of the Russian PMCs accused of brutalities on the frontlines, election interference, and the suppression of demonstrators.

Conclusion

Russia’s international response to the coronavirus crisis is telling of its foreign policy priorities. While not completely deaf to the humanitarian concerns and capacity challenges of the countries affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, Moscow has nevertheless taken advantage of the humanitarian cause to advance its military cooperation, create new economic ties, and gain geopolitical support.

The Kremlin might have scored points by presenting itself as a responsible global power delivering much-needed medical supplies at a time of U.S. retrenchment. Its political gambles under the guise of humanitarian COVID-19 assistance were fleeting. When the pandemic hit hard at home, the Kremlin put its humanitarian ambitions on hold. Russia’s ability to translate its humanitarian contributions into political leverage has been further limited by global, regional, and country-specific factors, such as competition from China and self-interested local actors. When politics cripples decisions about humanitarian aid, the outcome is that the time-honored norm of humanitarianism loses its legitimacy and original purpose.

Yet, Russia’s meaningful humanitarian aid could be acknowledged by the international community and used to encourage greater transparency in Moscow’s humanitarian deliveries and greater engagement with international mechanisms for coordinating assistance. Greater international engagement, in turn, can lead to increased capacity and independence of non-state Russian humanitarian entities and a shift away from predominantly state-to-state funding. While the Russian government will lose a degree of influence over humanitarian aid efforts, the important trade-off for Russia will be an improved reputation on the global humanitarian stage.

Mariya Omelicheva is Professor of National Security Strategy at the National War College.

All views presented in this policy memo are those of the author and do not represent an official position of the U.S. government, Department of Defense, or National Defense University.

PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 727