Since the Wagner mutiny of June 2023, the role of paramilitaries in Russia has become a subject of intense scrutiny. Not only do such groups represent a diminution of the state’s monopoly on violence—and so raise the possibility of civil war or warlordism—but they also speak to Russia’s ability to wage a long-term war without resorting to another draft. This, in turn, has implications for the seeming paradox of the war’s continued popularity: so long as it is not affecting daily life, it is unlikely to generate much resistance. Yet the rise of such groups has not occurred overnight, and it is only now that the subterranean stream of violent paramilitarism has risen to the surface. This memo summarizes and extends a report previously submitted to SONAC, part of the UK Ministry of Defence, focusing on perhaps the largest and most consequential of these paramilitary groups, the registered Russian Cossacks. How do the registered Russian Cossacks illustrate ongoing paramilitarization?

We define paramilitarization as a concept that goes beyond simply the demand for paramilitary forces to act as forces on the battlefield. The concept also includes those entities that prepare young men—and in the case of Russia, the process is distinctly gendered—to work in military structures, whether official or not. This includes ostensibly educational exercises, institutions, and competitions promoting an ambient militarism that steels society for conflict. Both dimensions of the concept are important to explaining the resolve of Russia’s forces in the field. This memo presents the Russian registered Cossack movement as a case study of both tendencies within the larger paramilitary movement.

The Registered Cossack Movement

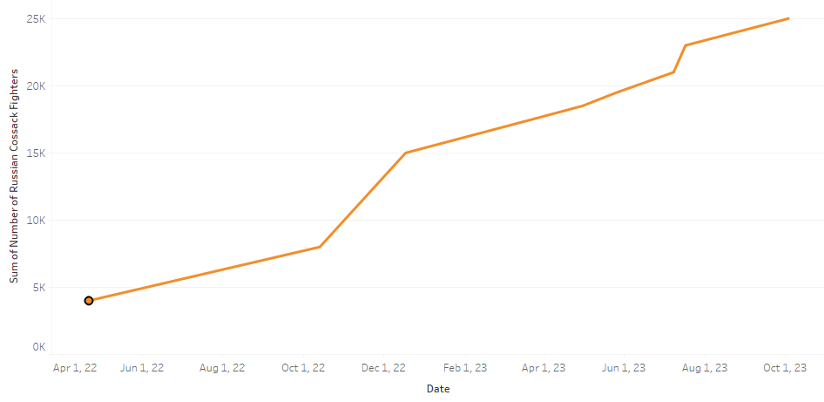

The registered Cossacks are an excellent case to illustrate demand and supply factors, both because they exhibit these tendencies in stark fashion and because they have heretofore been ignored by the Western media. Given the interest in private users of violence after the abortive mutiny of Prigozhin’s Wagner forces in June 2023, this neglect is all the more surprising. Yet as Figure 1 demonstrates, the Cossacks have contributed some 25,000 troops to Russia’s invading forces (taking into account leaves and rotations). News articles state that there are 146,000 registered Cossacks in Russia today: excluding the 29,000 students and 58,000 members who are over the age of 60, that leaves 60,000 in “prime” fighting age, making them the largest semi-autonomous armed formation in Russia’s Ukraine venture of which this analyst is aware. Likewise, the 29,000 students who are being prepared for service testify to how the Cossacks fulfill the supply side of paramilitary organizations.

Figure 1. Number of Russian Cossacks fighting in the war since February 24, 2022

The registered Cossack movement has evolved in tandem with the Russian regimes of the post-Soviet era. Upon their mobilization by descendants of the pre-revolutionary Cossack hosts that existed under the Tsar at the end of Communism, Cossacks opposed the Russian state and called for their own ethnic republic in the North Caucasus. There was even some discussion of autonomy for the Don region based on its Cossack heritage. The relationship, however, went “from confrontation to collaboration,” in the words of Russian scholar Olga Rvacheva, with the 1995 establishment of the Cossack register, under which individuals and organizations could sign up to perform state service. The register is an accounting of Cossacks who are ready, if called upon by the state, to perform a number of tasks in exchange for payment. While many ancestral Cossacks did not sign up to the register, one could suddenly become an “asphalt Cossack” (a derogatory term questioning the authenticity of the claim to be a Cossack) through service. Those services expanded in 2005 and 2012, and in 2018 the government established the “All-Russian Cossack Society,” which centralized the 12 voiskas (societies, hosts, or armies) that cover the territory of the Russian Federation. This is where the 25,000 Cossack volunteer soldiers fighting in Ukraine originated from, and it is those regional organizations that arrange educational activities for youth.

At the same time, the lands where the war is being fought hold a special meaning for those—both Ukrainian and Russian—who claim to be Cossacks. This exemplifies Arel and Driscoll’s (2022) description of the Ukraine crisis as a “civil war within the Russian-speaking world.” The importance of the Cossack archetype for Ukrainian national identity is well-documented. A meeting in Moscow of social Cossack organizations underlined the importance of the land for Russian Cossacks as well, describing Kherson, Zaporizhzhiya, and Dnipropetrovsk as “the land watered by the blood of our ancestors” and Russia’s invasion as a “holy war.” In harnessing such para-state organizations to serve its own ends, Moscow embraces and encourages the future development of paramilitaries.

Demand for Cossack Volunteer Fighters

Following the initial round of mobilization in September 2022, when Russia forced 300,000 men into military service, the Kremlin has been reluctant to launch a second round and is unlikely to do so in advance of the 2024 presidential “election.” To be sure, more men are needed at the front, which has led to creative schemes to increase the manpower of Russia’s army. We are already used to seeing videos of Russian military men trawling prisons and dangling the prospect of commuted sentences in exchange for service, but one underreported mechanism has been the BARS system. BARS (Boevoi Armeiskii Rezerv Strany, Special Combat Army Reserve) is a reserve system akin to the United States Army Reserve or the British Territorial Army. The system recruits men, many from the poorest regions, and offers them a lucrative salary to participate in hostilities. The salaries are advertised on the BARS website, but reports say that few salaries are paid as reported—and they are sometimes not paid at all. For instance, Yevgeny from BARS-5 fought in Ukraine for two months and was promised 410,000 rubles. He claims only to have received a little more than 32,000 rubles. A variety of other questionable “mistakes,” such as misspelling names and “losing” bank details, have also led to non-payment of promised salaries.

Likewise, the BARS website promises professional training and state media report that “the training of the BARS detachments is being carried out at eight training grounds by 845 military instructors with modern combat experience.” However, other reports suggest that the training actually given has been insufficient and the equipment sub-standard. Individuals who register for military service with BARS sign contacts with the Ministry of Defense, but their legal status is murky. The parties to the contract are “Volunteer” and “Management,” and no legal entities are named in the document. While recruits are not technically in violation of Article 359 (“On Mercenaries”) or Article 208 of the Criminal Code (On Participation in Illegal Armed Groups) because they are fighting in the interests of Russia, human rights lawyer Sergey Krivenko has claimed that the BARS battalions amount to “the creation of illegal armed groups by the Ministry of Defense.”

It is difficult to be certain of the number of BARS battalions fighting in Ukraine, but some of them are definitely staffed by Cossacks who get to name their battalions with Cossack symbols as a special privilege. The state-run (“registered”) Cossack movement thus plays an important role in the demand side of paramilitarization in Russia. The program was first announced by the Ministry of Defense in 2021 and by November 30, 2022, there were reportedly 20 such BARS units. Recent rumors suggest that as many as 32 BARS units are now in operation, with at least three coming from the armies of the LNR and the DNR. The most recent unit of which this analyst is aware is the BARS-32 unit, constituted by volunteers from the region of Zaporozhzhia. Of these 32 brigades, at least 18 are made up of “Cossacks” who signed up for state service even prior to the invasion. By region, three battalions are from the Krasnodar region (Kuban), three from Stavropol (Terek), two from Rostov (Don), one from Crimea (Black Sea), one from Orenburg, one from the Volga and Orenburg, one from Primorskii (Ussuriskii), one from the Trans-Baikal region, and one from the Union of Cossack Fighters of Russia and Abroad (as of June 7, 2023). There are also signs that the Russians are using the popularity of the Cossack idea in Southern Ukraine to recruit Ukrainian citizens to fight for Russia, as in the case of the Dnepr battalion. While many, possibly even most, of these recruits were members of Cossack organizations prior to the war, it is probably also true that some have enlisted in Cossack structures expressly to volunteer. Thus, erstwhile social-militant organizations are being drafted into official military service. Yet as the next section demonstrates, they also work to create a supply of recruits for future military ventures.

Supply of New Recruits for Paramilitarization

The concept of “paramilitarization” also contains what might be described as a supply-side dynamic. This refers to the preparation of primarily young men for participation in the military. By preparation, we mean both physical challenges designed to ensure young men achieve the requisite level of military readiness and psychological (or “spiritual”) preparation. These are primarily provided through the Cossack Cadet Corps, broader educational classes, and sports competitions, including those demonstrating martial strength. There is also a hard-to-measure tutelary effect on society, as frames of military glory strengthen resolve for a long conflict.

The Cossack Cadet Corps (Russian acronym KKK) is a separate institution from schools, which carry out regular pedagogical functions under a different model of education. According to longtime (now former) Cossack ataman of the All-Russian Cossack Society and current Duma deputy Nikolai Doluda, “It is impossible to carry out a full-fledged Cossack cadet education in a multidisciplinary educational institution, as is proposed by the Orenburg region. The ‘Cossack component’ presupposes a completely different regime, a different organization of the educational process, and different relationships in the team. A Cossack mentor is an obligatory figure here. Along with mastering the compulsory disciplines of the main educational program, the patriotic education of children, their knowledge and observance of Cossack commandments and awareness of what Cossack honor is, what Cossack brotherhood is, what service to the Motherland is, are also paramount.”

There are a total of 31 Cossack Cadet Corps. Astrakhan, Bryansk, Kurgan, Moscow, Novosibirsk, Penza, Samara, Kalmykia, Penza, Perm, Stavropol, and Sverdlovsk each have one. There are two KKK organizations in each of Voronezh, Volgograd, and Luhansk. Rostov has six organizations and Krasnodar seven. There are concrete plans to open new KKK organizations in Stavropol, Khabarovsk, Trans-Baikal, Krasnoyarsk, Irkutsk, Omsk, and Orenburg regions—making the KKK primarily a regional phenomenon. Although one imagines some variation in size between these organizations, the average appears to be around 500 enrollees.

These KKK organizations hold friendly competitions against each other. One competition that pits young “Cossacks” against each other is for the title of “Best Cossack Class.” According to the announcement, the competition has three rounds and team size is 14 students aged 11-16. In the first round, held online, participants choose between the categories of “Cossack Museum,” “Cossack All-Rounder,” and “Guardian of Tradition;” the 20 teams with the highest number of points advance to round two. Similarly, “the Union of Cossack Youth of Russia” participates in the “Ready for Work and Defense” (GTO) program, a Soviet-era relic that has been revived. Young people can earn their insignia for the GTO, designed to inculcate what Nikolai Doluda describes as “a desire for a healthy lifestyle, physical improvement and readiness to become a worthy defender of their Fatherland in the future,” through participation in Cossack organizations. Such quasi-martial activities prepare young Russians both mentally and physically for recruitment into the army or other military-adjacent structures.

At the regional level, too, there is a process through which the most promising recruits are identified. The all-Russian Spartakiade and the Cossack Flash competition took place in the village of Samordovo, Orenburg region, in September 2023. Cossack Flash takes the form of several competitive tests: Scout’s Stripe, made up of competitions in military-applied sports (including chess, mini-football, and drill training); the team competition Cossack Triathlon, in which young men compete in running, cutting vines with a sword, and fire training; and the Cossack song contest “At the Campfire.” This plethora of competitions help ensure the physical readiness of the Cossack reserve.

In addition, a system of Cossack education is being constructed throughout Russia. Existing Cossack kindergartens and schools are being supplemented with university-level training. From direct sources whose identity cannot be revealed for safety reasons, I can attest to plans to expand Cossack university education (including in the form of postgraduate degrees) across the entire country. Such education equips would-be Cossacks with the values and, increasingly, the training to go into the military.

The first cohort of Bachelor’s degree students enrolled in Razumovsky Moscow State University of Technology and Management (the First Cossack University) in 2023. The degree has four specializations: journalism, administration, teaching, and animal husbandry. The curriculum they follow combines “classical humanitarian education with practical and applied disciplines, as well as a separate block on the history and the culture of the Cossacks.” True to form, the Cossack authorities offer university students prizes in a competition titled “Cossacks in Service of the Fatherland.” One post suggests that there are now “15 ‘Cossack’ universities” in Russia, referring to those universities that have recruited a total of 800 students into specifically Cossack-themed programs for the upcoming academic year. The titles of such courses and associated activities suffice to illustrate the paramilitarization of Russian youth.

Conclusion

Cossack activities in Russia are a case study of the country’s ongoing “paramilitarization.” So-called “asphalt Cossack” (a mocking term for inauthentic Cossacks) institutions both provide men for service in Russia’s conflicts—including the “special military operation”—and prepare youth physically and mentally for future service. In this way, the Cossacks fulfill both the demand and supply sides of paramilitarization, doing so in a way that constructs para-state entities. Notably, while the Cossacks are only one of several organizations performing this function, they appear to have constructed a more comprehensive and developed web of institutions than the other cases of which I am aware. Perhaps this is a consequence of the persistence of indigenous Cossack populations in the region, which may make the archetype more authentic and appealing.

Richard Arnold is Associate Professor of Political Science at Muskingum University and a regular contributor to the Jamestown Foundation’s Eurasia Daily Monitor. His research interests focus on paramilitarization, sport, nationalism, and the Cossack movement in Russia and Ukraine.