This past January, residents of Troitsk, a research town (naukograd) of over 60,000 inhabitants to the southwest of Moscow, gathered to protest against the cutting down of a forest for a new 2,100–student school. The protest quickly escalated into clashes with workers leading to injuries. Beforehand, the residents petitioned the government, organized public rallies, and contacted officials at multiple levels to try to prevent the damage. The activists said they were not against the school but against clearing away the large green space. For their part, the authorities insisted that the construction was legal and “would not harm the ecosystem.”

Conflicts over urban development like in Troitsk have been flourishing across Russia over the last two decades. From Moscow’s controversial apartment renovations to Ekaterinburg’s mobilization against the location of a new church, the conflicts show the significance of urban development in the structuring of state-society relations. This memo identifies key dimensions of this mobilization—including intensity, duration, issues, and outcomes—through a new dataset that covers place-based conflicts in cities with over 1 million inhabitants (millionniks) covering 2010 to 2020. Differences across the cities and the political implications of the conflicts are also shown. The findings shed light on the rationale behind governmental initiatives developing “comfortable cities” (with higher-quality public goods) aimed at curtailing social unrest by pacifying urbanites.

Post-Soviet Urban Development in Russia

There have been dramatic changes in urban landscapes across Russian cities during the last two decades. Russian cities inherited much from Soviet times, from strategic planning documents that outline spatial development to deteriorating infrastructure, lack of green space, and large industrial areas within urban borders. Land commodification, economic growth, and low interest rates led to increased demand both for housing and business development. As regulations lagged and developers filled seats in municipal councils to control the agenda and the implementation of land use and development legislation, infill construction, encroachment on urban commons, and social housing sprawled.

Citizens responded to these developments with a wide repertoire of collective actions. In the late 2000s, protests over local issues constituted the bulk of contention, with some groups coordinating across cities. Some of the most resonant cases of urban protests took place in St. Petersburg (against the Okhta-Center skyscraper construction) and Moscow (against the toll road in the Khimki forest). The engagement of local residents with urban governance was further amplified by the 2011-2012 “For Fair Elections!” campaign, with groups and initiatives emerging like “Beautiful St. Petersburg,” “Tom Sawyer Festival,” and “Injured Novosibirsk.” These promoted more inclusive and accountable urban governance, transparent planning policy, and larger public investments in urban infrastructure and public spaces.

In an attempt to bring order to urban development, the central government adopted the Town Planning Code in 2004. It requires each municipality to develop a general plan that ties together strategic projections of socioeconomic and demographic trends with spatial development. The Code also incorporates the concepts of legal zoning and public hearings into the legal and institutional framework of urban development. It specifies the directions set by the general plan by assigning requirements to construction projects for every “functional area,” such as the purpose of buildings, the number of levels, construction density, etc. Land Use and Development Rules (LUDR) are usually adopted by the city council and provide specific guidelines for development projects. Their public hearings are an instrument for organizing consultations with citizens on construction projects as well as changes to general plans, land use, and development rules. Although hearing results are not legally binding, they constitute an integral part of the development process, offering a pretext to cancel projects that do not align with majority public opinion.

In theory, LUDR and public hearings should strengthen public participation and tame the appetites of developers and public authorities. In practice, however, substantial barriers exist for the public to engage in planning processes. For example, information about public hearings (agenda, place, and time) is rarely easily accessible, and developers often bring their supporters to boost their agenda and outflank oppositionists. With city executives able to circumvent hearings and developers often sitting on city councils, LUDRs can be bent in their favor.

Land-Based Conflicts in Russian Cities

Land-based conflicts are ubiquitous in Russian cities. Most conflicts stem from multiple loopholes in legislation and power imbalances that allow developers and public authorities to build alliances in pursuit of their own interests. Studies show that issues like infill construction, encroachment on urban commons (squares, parks, and embankments), and infrastructure projects have elicited intense responses and mobilized thousands of urban dwellers. Generally, for developers, finding and using a pre-zoned downtown spot to build a multi-level housing or office building is easier and more profitable than embarking on a greenfield project on the outskirts of town. Consequently, issues like infill construction in and near large cities became a part of the political agenda. For example, Communist Party candidate Anatolii Lokot’ highlighted infrastructure issues (bridges, metro stations) in Novosibirsk as his key talking points in his 2014 and 2019 mayoral campaigns. As an example of local differentiation, in Tyumen, infill construction is “prohibited” by LUDR.

To understand the scale and the depth of urban conflicts, we gathered data on land-based mobilization in millionniks. The data comprise cases that started in 2010-2014, some lasting just one month, others for almost ten years. Using multiple media sources, for each conflict, we reconstructed interactions among the key actors—citizens, public authorities, developers, and “third parties.” Consequently, the data represent sequences of dyadic interactions nested in the context of a particular conflict episode. This structure allows us to compare the mobilization across the cities.

Table 1 below presents the breakdown of the number of conflicts and interactions, the average count of conflict actions, and the mean duration for every city in the analysis. The largest cities lead the chart with over 30 conflicts each. Six cities occupy the middle of the distribution with 10-17 conflicts, and another six have fewer than 10 cases. The table also indicates that the city’s rank by the number of conflict episodes does not necessarily relate to the rank on other scales. In terms of the number of interactions, St. Petersburg is ahead of Moscow by 80, while Ufa had the most intensive conflict, one over the construction of the “Kronshpan” facility that resulted in the highest action-to-conflict ratio. On the other hand, Voronezh is distinguished by the highest level of conflict durability, with a mean duration of 2.5 years. In other words, there is substantial variation across the cities in terms of key features of conflict.

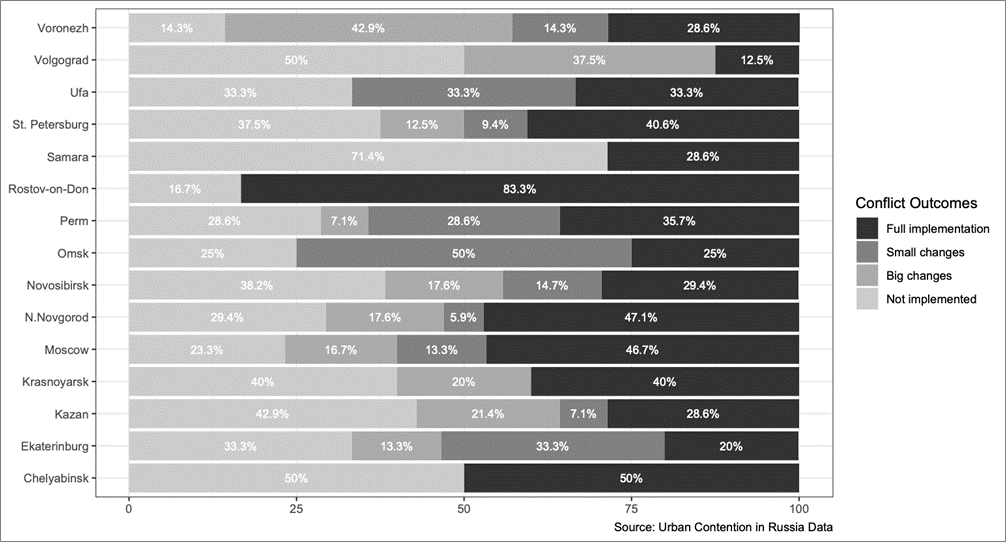

There is also important variation in the conflicts’ outcomes. Overall, we found that 74 (36 percent) of the projects being protested were fully implemented in the end vs. 71 (35 percent) that were canceled. Concessions were also almost evenly distributed, with 28 (14 percent) cases resulting in “small changes” to the projects and 32 (16 percent) in “big changes.” In sum, to our surprise, almost half of the projects were either canceled or substantially modified as concessions to protesters.

Table 1. Conflict Episodes in the Largest Russian Cities

Cities ranked first in each column are in bold.

| City | Number of conflicts | Number of interactions | Actions per conflict | Mean duration (in months) |

| Novosibirsk | 36 | 228 | 6.3 | 13.8 |

| Moscow | 34 | 263 | 7.7 | 12.8 |

| St. Petersburg | 33 | 343 | 10.4 | 14.7 |

| N. Novgorod | 17 | 191 | 11.2 | 15.1 |

| Ekaterinburg | 17 | 173 | 10.2 | 11.1 |

| Perm | 14 | 121 | 8.6 | 15.5 |

| Kazan | 14 | 105 | 7.5 | 13.9 |

| Krasnoyarsk | 11 | 70 | 6.4 | 10.5 |

| Volgograd | 10 | 78 | 7.8 | 17.3 |

| Voronezh | 7 | 61 | 8.7 | 30.4 |

| Samara | 7 | 43 | 6.1 | 15.1 |

| Rostov-on-Don | 7 | 24 | 3.4 | 10.2 |

| Ufa | 6 | 132 | 22.0 | 12.5 |

| Omsk | 4 | 28 | 7.0 | 11.3 |

| Chelyabinsk | 3 | 16 | 5.3 | 12.5 |

| Total/Mean | 220 | 1876 | 8.5 | 14.4 |

Across the millionniks, the exact mix can vary: Figure 1 below demonstrates that in Rostov, developers and authorities are very reluctant with almost all projects (6 out of 7) being fully implemented, and in Samara, the situation is the opposite. However, it is remarkable that overall there seems to be a balance between successful and failed mobilizations regardless of local context. Of course, media bias can make its way into these calculations because the quality of conflict coverage also varies across the cities. Nevertheless, these data show that, unlike qualitative studies that deem urban collective actions in Russia futile, in fact, citizens are almost equally likely to win or lose the fight against the powerful alliance of developers and public authorities.

Figure 1. Conflict Outcomes in the Largest Cities

Conclusion

What are the political implications of urban conflicts in millionniks? On the one hand, it is hard to see any direct electoral consequences regardless of the scale or intensity of mobilization. Most of the conflicts remain too small to change the balance of power and mobilize an electorally meaningful amount of voters against incumbent mayors or the ruling party. As a result, even if some collective efforts to preserve urban commons or prevent backyards from infill construction are successful, there is no guarantee that there will not be any further attempts to build over a local square or demolish an old merchant mansion in the downtown.

Nevertheless, the volume of urban conflicts allows us to look deeper into state-society relations in Russia. The character of mobilization implies that Russian urbanities care most about their personal space and are willing to fight over it even if the opposite side is much stronger. It contains NIMBY (“not in my back yard”) sentiments similar to those in protective residential communities around the world. Another point is that among multiple means to defend urban spaces, city dwellers largely rely on “elite-enabling” participation, which Danielle Lussier describes as collecting citizen feedback behind the scenes in a way that reduces dissatisfaction. But even these “enabling” interactions have political consequences as urbanities learn that the state is not as caring and responsive as it appears on TV.

The regime recognizes the challenge of quieting discontent urbanites. Cities are home to the majority of voters: Moscow and St. Petersburg together account for 10 percent of eligible voters, and in most other regions, citizens gravitate toward urban hubs. It is thus not surprising that the regime uses “renovation” programs to reward or punish city dwellers and develops nationwide programs that emulate successful policies in the capital. Hosting a diverse and resourceful population, Russian cities provide venues for coordinated actions, facilitate the development of dense social networks, and remain the site of major contention. While this contention falls short of transforming the regime, especially after February 24, 2022, it slowly changes state-society relations, reminding citizens that they are tied to particular places and forcing them to stand against the authorities.

Andrei Semenov is Senior Researcher at the Sociological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences. This memo was written before the unjustified Russian invasion of Ukraine. Data was collected under Russian Scientific Foundation grant, RSF № 18-78-10054-P (“Mechanisms of interests coordination in the urban development processes”).