Qazaqstan emerges as one of the most vulnerable countries to the consequences of climate change. According to the national hydrometeorological service Kazhydromet, the average annual temperature in the country increases by 0.33°C every 10 years. Global warming brings more extreme weather events such as heat waves, droughts, and floods, and exposes the country to multiple hazards. The country’s top leadership recognizes the importance of the issue: President Tokayev frequently mentions climate change as a key challenge that requires international cooperation, for example, at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization Plus summit in Astana in July and at the 78th session of the UN General Assembly. Qazaqstan signed the Paris Agreement on November 4, 2016, becoming the first country in the region to do so, and in 2023 adopted the national decarbonization strategy with the commitment to full decarbonization by 2060.

Yet, Qazaqstan lacks a comprehensive policy framework to tackle the consequences of climate change. In this memo, we argue that, similar to other Eurasian countries, powerful interest groups, deficiencies in intragovernmental coordination, low public salience, and lack of subnational autonomy prevent the largest Central Asian economy from making further improvements in climate governance. At the same time, the country has an advantage in scientific and civil society expertise, as well as connections to the key international players that might help to overcome existing challenges. Anticipating the Regional Climate Summit in 2026 in Astana, Qazaqstani authorities, civil society organizations, and international actors can do much more by leveraging the existing expertise and knowledge and taking “bold steps” towards “a sustainable future for all.”

Climate Change Governance in Qazaqstan

Despite the 2022 constitutional reform, which aimed at re-balancing between branches of power, the president remains at the center of decision-making in Qazaqstan. The chief executive sets the agenda and frequently intervenes in the operations of the national government. President Tokayev’s tenure has been marked by increased Qazaqstan’s engagement with global issues: apart from the “multivector” foreign policy established by his predecessor, he consistently emphasizes the need for regional and global cooperation. His position on climate change aligns with that of other developing countries: in his view, decarbonization measures should be balanced with development and modernization. For the domestic audience, the president also makes an effort to show the drastic consequences of climate change on the country’s economy and well-being. For example, following the devastating spring 2024 floods, Tokayev directly linked the frequency of natural disasters to rising global temperatures.

However, the strong presidential pro-climate rhetoric has been only partially translated into a cohesive policy framework. While Qazaqstan joined the 2015 Paris Agreement early on, its actual level of ambition remains rather moderate: the renewed 2023 commitment goals are a 15% “unconditional” reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions below 1990 levels by 2030 and a “conditional” 25% reduction. The same document lists reasons that complicate the achievement of these goals, including rising energy prices for consumers, lack of affordable financing for low-carbon projects, and interdependence with other countries in the region.

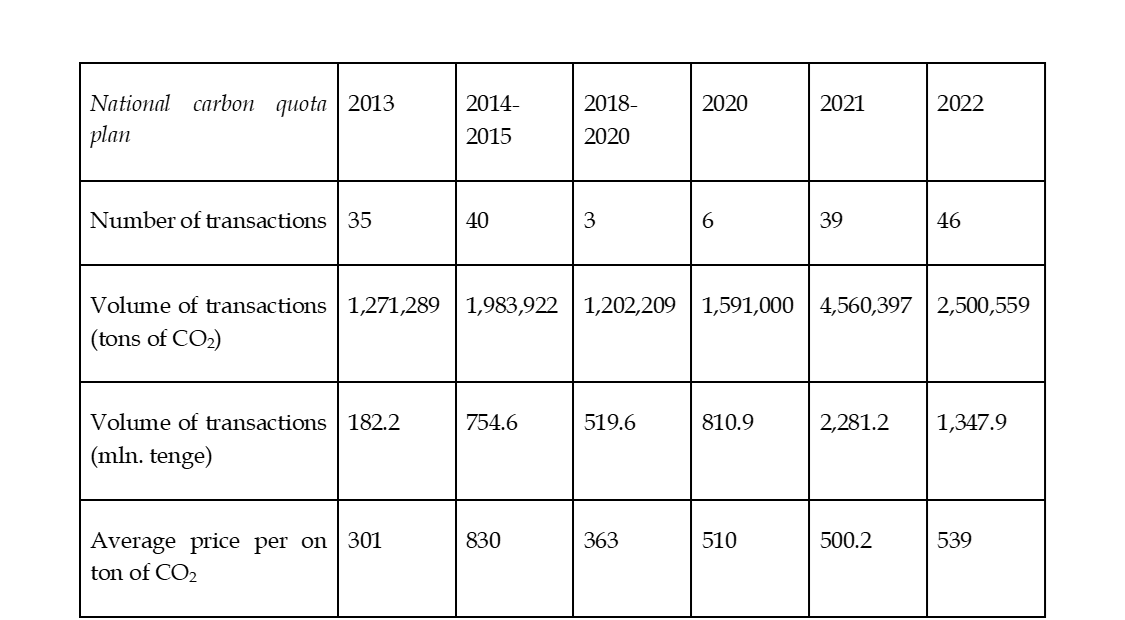

The government is responsible for implementing the Paris Agreement. In 2023, it adopted a strategy to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060, which includes a range of sectoral and cross-sectoral measures, including adaptation and carbon emission regulations. Some elements of this strategy have already been implemented; for instance, since 2013, the emission trading system (ETS) covering key sectors of the economy has been in place. The government determines the carbon quotas through the National Carbon Quota Plan, but at present the system is dysfunctional: the quotas are generous and provided free of charge, while the market price for carbon credits is very low (in 2022, the average price was 539 tenge or about $1.25 per ton, see Table 1).

Table 1. Dynamics of carbon emission trading in Qazaqstan. Source: АО «Jasyl Damu»,

The National Carbon Quota Plan is linked to the state regulations of GHG emissions and absorptions, which establish the national carbon budget and the carbon unit allocation procedure. There are plans to tighten these regulations starting in 2026, an especially important step given the implementation of the carbon adjustment mechanism by the European Union in the same year. Other international commitments include joining the Global Methane Pledge, an initiative to drastically reduce methane emissions to levels consistent with 1.5°C pathways, and launching the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), a mechanism to help decarbonize developing economies. The government has also initiated projects indirectly dealing with climate change such as “Green Qazaqstan” which aims to “create a favorable living environment for the population and improve the environmental situations.”

The central governmental actor with regard to climate is the Ministry of Environment, Geology, and Natural Resources alongside its Department of Climate Policy and Green Technology. The national hydrometeorological service, Kazhydromet, under the Ministry monitors the situation and provides scientific and technical expertise. Also under the Ministry, the Department of Climate Policy and Green Technologies was established in 2022, but so far it has made news only following the detention of its head in February 2024. The Department supports initiatives such as the launch of the Central Asian Green Tech Climate Hub, a subsidiary of AIFC Green Finance Centre, which aims at the commercialization of “green” technologies,. However, its specific role in climate governance is hard to determine. Other Ministries, such as the Ministry of Energy and the Ministry of Industry and Construction, also have their say in climate governance: both are concerned with the EU’s carbon taxation and address issues related to energy efficiency and transition to renewable energy sources.

As for climate adaptation strategies, the government prioritizes adaptation in strategies in agriculture, water resources management, forestry, and disaster risk reduction. Most attention goes to the first sector, for which the government has developed a separate “Plan for adaptation of agriculture to climate change for 2025-2034.” The Ministry of Environment announced the start of the National Adaptation Plan (NAP). In partnership with the UNDP and the Green Climate Fund, it aims to “integrate climate adaptation issues into strategic planning in Qazaqstan” In 2021, the Ministry issued a decree titled “On the rules of organization and implementation of climate adaptation process”, which assigns responsibilities for the monitoring, development, and implementation assessment to republican and regional authorities. However, its integration with NAP and other strategic documents remains unclear. The government also emphasizes the importance of international cooperation in the region, as reflected in the 2023 “Regional strategy on climate change adaptation in Central Asia.”

Climate Change and the Public in Qazaqstan

If the government is reluctant to strongly commit to the climate agenda, pressure from political and civic society might generate action. Given that the 2022 constitutional reform–at least on paper–gave more power to the parliament, one might expect a more active role for political parties in elevating climate change on the political agenda. Indeed, the dominant party, Amanat, employs no climate change agenda. While it includes some elements related to environmental protection, it lacks a cohesive vision and concrete proposals for addressing climate change issues. Additionally, Amanat officials often defer the responsibility for tackling climate challenges to younger generations, rather than taking immediate, comprehensive action. Other political parties do not mention climate change either: even “Baytaq” (The Greens) refers to climate change only in relation to education programs.

Media coverage of climate change is sparse and mostly emerges in relation to national emergencies. For instance, after the 2024 floods in several Qazaqstani regions, journalists of Cabar Asia, TengriNews, Azattyq, and InformBuro published articles relating the cataclysms to climate change (much like President Tokayev) and discussed the need for adaptation with experts. Additionally, seasonal abnormal changes in temperatures, as well as reports by international and national organizations, occasionally make the headlines, such as “Catastrophic changes. What threats does the climatic chaos pose to Qazaqstan?” and “Where the wind blows from global warming is changing the climate in the Aral Sea region.”

Out of more than 43,000 registered non-profit organizations, 1,329 (3%) fall within the “environmental protection” category, and 142 are members of the Association of Ecological Organizations. However, many environmental non-profits are either inactive or have never been active. Among these, only a small fraction addresses climate change. For instance, UNDP promotes sustainable agriculture and low-carbon technologies, helps to integrate climate goals in strategic planning, and organizes various competitions for students and specialists on topics like climate change and urban adaptation. UrbanForum Qazaqstan, one of the leading non-profits in urban affairs based in Almaty, offers public lectures by experts, eco-festivals, and forums in partnership with the corporate sector and local initiatives. The latter, however, often operate outside of the governmental framework and are frequently underfunded, relying on occasional support from corporate or international donors.

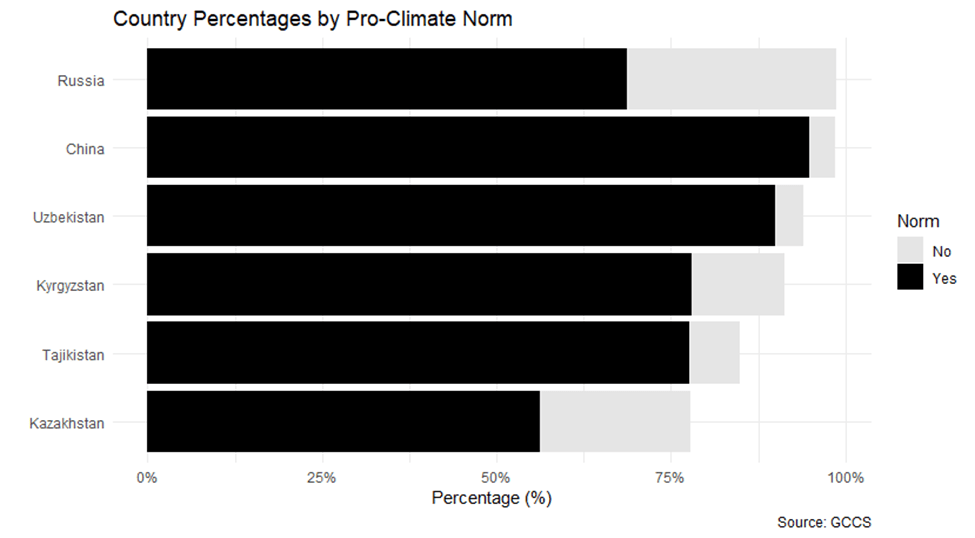

Alliances between media, NPOs, and the government aimed at raising public awareness of climate change occasionally spill into media contests such as “Change for Climate in Qazaqstan” by the UN, the “Climate Change Adaptation Measures in Qazaqstan” by the Regional Environmental Centre for Central Asia, and the ‘Climate Journalism in Central Asia’ project involve regional and national media. Despite these efforts, public opinion seems to lag. A recent Global Climate Change Survey (GCCS) indicates that only 45% of Qazaqstani citizens are willing to contribute 1% of their income to fight global warming, compared to the global average of 69%. Additionally, 78.7% believe that the government should do more – 11 percentage lower than the global average of 89%. Only 56% agree that their compatriots should “try to fight global warming”, compared to 86% globally, making it the lowest among Eurasian states (Figure 1). Systematic data on public attitudes towards climate change in Qazaqstan is absent, so it is hard to assess the overall mood. However, we can safely conclude the public and civil society are in the very incipient stages of engaging with the climate agenda.

Qazqastan and Global Climate Agenda

Qazaqstan has much at stake with the changing climate: changing weather patterns coupled with underdeveloped infrastructure and loose climate governance breed increased risks and fragility. On the one hand, Qazaqstani political leadership recognizes the importance of the issue and moves quickly to sign international agreements and develop national strategies. On the other hand, the level of international commitments is moderate at best, while decarbonization plans suffering from the lack of comprehensive legislative and policy framework.

The upcoming COP29 in Azerbaijan in 2024 and Regional Climate Summit Astana in 2026 present opportunities to advance the climate agenda on all levels. Qazaqstan has excellent financial, scientific, and technical expertise as well as extensive international networks; there is some experimentation on the local level with regards to raising awareness about climate change and building resilience; and the corporate sector seems to slowly but steadily recognize the benefits of decarbonization. Other nations in the region also pledge their commitment to the climate agenda, which is becoming a matter of international influence and bargaining. For Akorda to gain leadership, more efforts should be put into bringing together public and private actors and developing cohesive climate governance structures.

Andrei Semenov is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Political Science and International Relations at Nazarbayev University.

Akerke Akhmetova is an undergraduate student at the Department of Political Science and International Relations at Nazarbayev University.

Aizada Arapova is an undergraduate student at the Department of Political Science and International Relations at Nazarbayev University.

Aruzhan Kaparova is an undergraduate student at the Department of Political Science and International Relations at Nazarbayev University.