A woman lays flowers at the Katyn Massacre memorial.

► Several years ago Alexey Miller and I co-edited a volume titled, “The Convolutions of Historical Politics,” in which our contributors wrote about the uses and abuses of history in their countries of Russia and Poland, France and Germany, Ukraine and Turkey, China, and Japan. In recent years, history has become an inalienable part of political clashes, and “convolutions” have increasingly looked like “convulsions,” especially in the region of Miller’s professional interests (Russia and Eastern Europe). In his recent lectures and writings, Miller has even used the phrase “memory wars.” Below is our conversation about today’s “politics of history” in Russia and beyond. – Maria Lipman

Maria Lipman: You mentioned in a recent publication that the way memory is used has radically changed in the 21st century. What do you mean by that and why has it happened?

Alexey Miller: I was talking about a transformation of memory culture since the last decades of the 20th century. Back then, scholars observed in the “old” European Union a rise of what they described as a cosmopolitan memory culture. This culture assumed that discussions of the past should aim at reaching a consensus. In some sense, this consensus was built around the perception of the Holocaust, which came to be seen as the key event of the 20th century. Western European nations agreed that it was not just Germany, but all Europeans should share a responsibility for the Holocaust. This memory culture had its positive aspects, but it also had negative ones. At national levels, alternative approaches that appeared to challenge this consensus were censored and suppressed.

The term Geschichtpolitik, or “Politics of History” emerged in Germany in the context of an inter-German conflict and was used by those who condemned politicians’ interference in history. Their criticism was aimed at Helmut Kohl and his politics of a “spiritual and moral turn.” In fact, this protest against politicians’ interference in history was an element of political struggle – of attacks against Kohl by Social-Democrats.

Lipman: Who were his critics?

Miller: They were intellectuals and historians. And there were also historians on Kohl’s side. It is important that certain trends were suppressed at the national level if the proponents of the cosmopolitan discourse regarded them as a threat; a key element of that discourse in Germany was that Germans should be focused on their guilt, and only their guilt, not their sufferings or their pride and patriotism. In order to secure this perception, Western Europe adopted laws regulating conversations about the past. Such laws were passed not just in Germany. In fact, France was the first to pass a legal ban on Holocaust denial.

|

“Western Europe adopted laws regulating conversations about the past.”

|

This is the kind of memory culture that came to dominate in Europe. It included, among other things, textbooks co-authored by historians from different countries, for instance, a French-German combined book. The primary motive was that the memory should serve the purposes of reconciliation and repentance.

It should be noted that the “old” European countries were able to maintain relative dominance of the “cosmopolitan memory” because it suited their interests in the framework of a successful European Union that was secure in its future. And by the way, this was a very long process. Jacques Chirac admitted the involvement of French people in the Holocaust as late as 1995, 50 years after the end of WWII.

Lipman: What you are saying about “cosmopolitan memory” echoes Ivan Krastev’s recent book, After Europe, in which he mentions that the year 1968 had different meanings for Western and Eastern Europe. For the former, it came to be the triumph of cosmopolitan values. For the latter, it was a rebirth of the national spirit. Apparently, the transformation that you are talking about is a rejection of “cosmopolitan memory” as it was thought out in Western Europe. Does it have to do with Eastern European nations’ active engagement in nation-building following the collapse of Communism?

Miller: I think it’s more complicated because we’re talking about a clash of different memory cultures. In the framework of this clash, a memory culture that may be referred to as antagonistic begins to prevail in the 21st century. The reasons cannot be reduced simply to nation-building. It also has to do with international relations. Since Holocaust was the pivot of the “old” consensus, the countries of Eastern Europe integrating in the European structure – if they had been sincere and consistent – should have focused on the problems stemming from their own responsibility. In almost all those countries, local populations were involved in the Holocaust – some to a larger extent, some to a smaller extent – but either way their involvement was substantial. If they had admitted their own responsibility, they would have been unable to claim the role of a major victim, or even the main victim, in their own view.

|

“In almost all those countries, local populations were involved in the Holocaust – some to a larger extent, some to a smaller extent – but, as a rule, the involvement was substantial. And if they had admitted their own responsibility, they would have been unable to claim the role of a major victim.”

|

This claim was very important to them, not because of the needs of nation-building, but because they needed to carve out space for themselves in the European balance of forces. Obviously, they can’t claim a leading role based on their economic weight. They remain, up until this day, recipients of substantial economic aid. And which role is more appropriate if you’re seeking economic assistance? You should be a victim so the donor would feel his responsibility for your sufferings. This idea had been already stressed by Milan Kundera in his famous 1984 essay “The Tragedy of Central Europe” in which he claimed that the West had sanctioned the “theft” and suppression of Central Europe by the Soviet Union. And in the post-Communist period, countries of “new” Europe have sought to preclude the West from making foreign-policy “deals” that would compromise their interests.

Besides, to the countries of Eastern Europe, Russia was not a potential partner, it was the main threat, in part because some of those countries had relatively large Russian or Russian-speaking minorities, and in part because this became an element of political struggle. If you need to undermine your domestic Communist rivals, as well as the Russian minorities’ claims for citizenship and cultural rights, you present them as agents of Moscow. There was a range of motives, and as a result, Eastern European countries came up with their own vision of 20th-century history centered on the concept of totalitarianism. For, if the main issue, if the main tragedy is the Holocaust, then the Red Army that put an end to the Holocaust and liberated Auschwitz can’t be equated with the Nazis. But in a system centered on totalitarianism, “red terror” is no different from “brown terror.”

Lipman: But was there not a chance – at the early stages of post-Communist development – of Russia and Eastern European nations adopting a shared approach – that it was “our” common catastrophe that we are now trying to overcome, whether we call it totalitarianism, or communism, or whatever? Of course, Eastern European countries had been occupied, but they had their own communists and those who upheld those regimes.

Miller: I would say there were certain hopes that this trend might prevail. These hopes were entertained in Moscow. Early on, there was an idea that if we admitted the existence of the secret protocol attached to the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact and condemned it, this would pave the way for reconciliation. This was done back in 1989, still the Soviet Union, at the Congress of People’s Deputies. But when Russian-speaking people in Estonia and Latvia were denied their right of citizenship under the pretext that they were a legacy of the Soviet occupation, it became clear that not everyone was playing the same game.

|

“Looking at the Russian “policy of memory” we see that it was opportunistic.”

|

The Genocide Museum in Lithuania is not about the Holocaust, it’s about the Soviet occupation, and it was created in 1992. A room dedicated to the memory of the Holocaust appeared in this museum as late as 2011.

Looking at the Russian “policy of memory” we see that it was opportunistic. When Russia’s counterparts demonstrated an interest in a dialog, Russia joined in. Russian-Polish relations in 2009-10, under prime-minister Donald Tusk, can be a good illustration. But in the 1990s nobody in Eastern Europe was keen to commemorate shared sufferings under the sway of the Soviet Union; each nation commemorated its own sufferers.

Russian Prime-Minister Vladimir Putin and Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk commemorated the 70th anniversary of the Katyn Massacre in 2010.

Lipman: So not only was the political use of history not abandoned, it evolved as a non-stop confrontation in which history became a bludgeon used by countries to bash each other, especially in relations between Russia and the Baltic states, Russia and Poland, Russia and Ukraine. How did that happen?

Miller: The 2000s were marked by a gradual securitization of memory issues and a strong focus on these issues both at international and national levels. So when Russia seeks to condemn the Ukrainian movement of 2012-14, it associates it with radical Ukrainian nationalism of the 1940s-50s. When the North Stream pipeline is compared to the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact and this comparison is used as an argument against its construction, this clearly points to the securitization of memory. The use of memory has been operationalized.

Interpreting the 20th century defines our current understanding of Europe. Therefore, it is crucial that we get a clear idea of what the 20th century was about? Do we see Stalin and Hitler as instigators of WWII equally responsible for all its horrors? Or do we admit that the Red Army made a major contribution to putting an end to the Nazi terror? In the latter case, how can Russia be regarded as the main criminal of the 20th century and as a constitutive Other for today’s Europe?

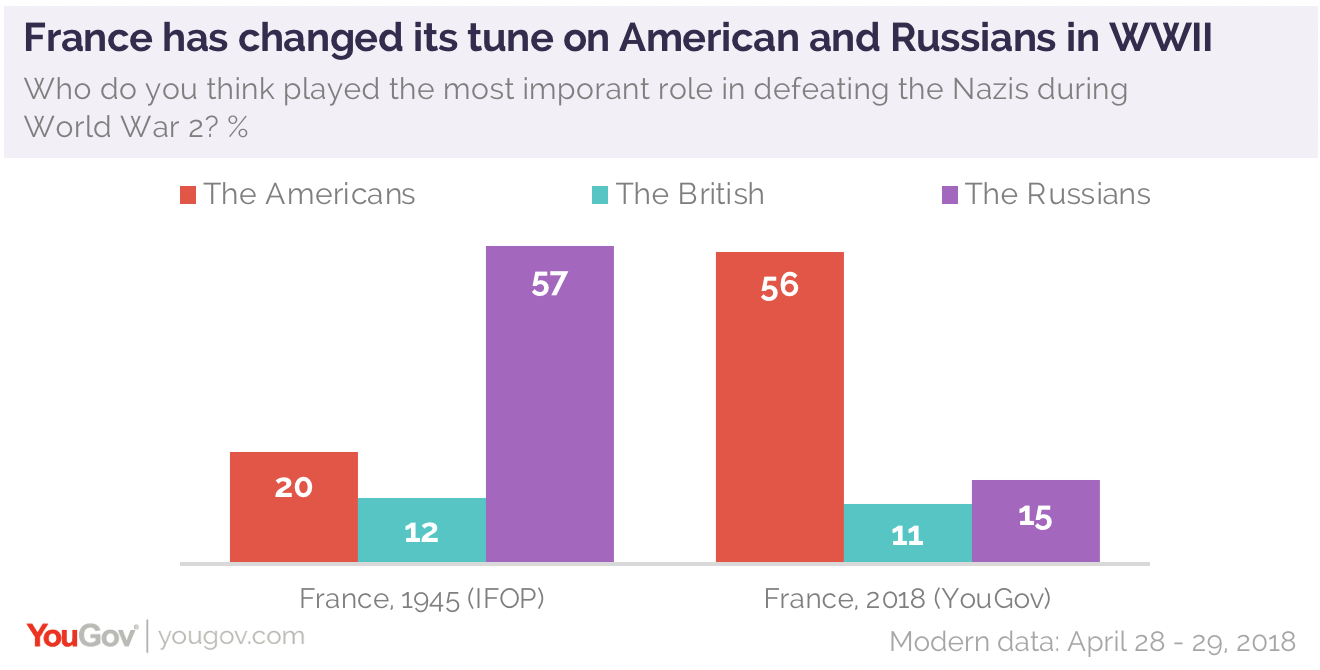

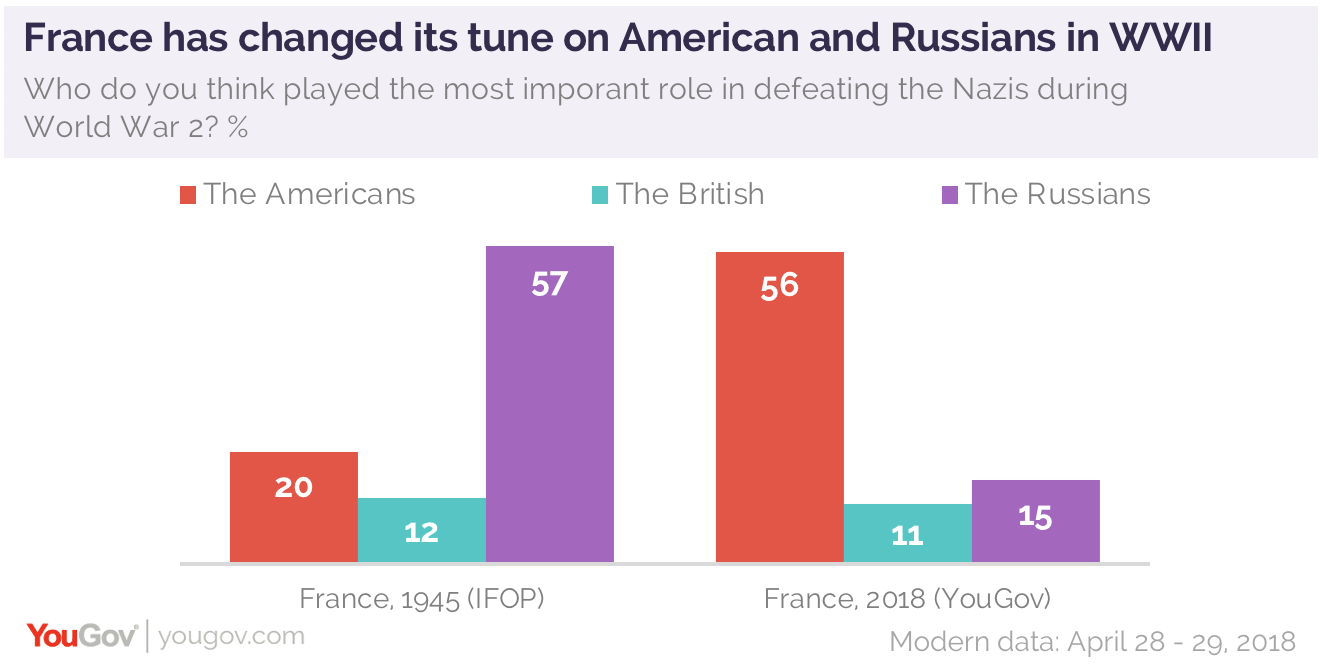

Lipman: It is worth mentioning that during the decades since the end of WWII the number of those in Europe who believe that Russia/Soviet Union made the largest contribution to the victory over Nazi Germany has sharply decreased. These days a common perception is that the contribution of the United States was the largest. There is comparative data on perceptions in France. And this is not because Russia and France are engaged in a hard confrontation.

Miller: There are few, if any, European countries that believe that the Soviet Union contributed the most to the victory. This shift in perception makes it very easy to explain to people in Russia that Europe is alien to Russia and that it is dishonest. And this also helps to understand why back in 2009, when speaking about the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, Putin said that “any form of collusion with the Nazi regime was morally unacceptable” and six years later he said that the pact “made sense from the point of view of security”.

“Without any doubt, we can rightfully condemn the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact made in August 1939. The year before France and England signed in Munich a well-known agreement with Hitler having thus crushed all hopes of creating a unified front of struggle against Fascism. Today we understand that any form of agreement with the Nazi regime was unacceptable from a moral standpoint and had no prospects from the point of view of practical realization.” – Vladimir Putin

|

“Every state has its own line, its own interest, or if you like, its own truth.”

|

The transformation of the politics of history in the early 21st century has rejected the notion that the dialog about the past between different groups and, first and foremost, between different states and nations should lead to reconciliation and alleviate tensions. This new concept (which, in fact, has always existed, but these days has come to the fore and gained legitimacy) has it that every state has its own line, its own interest, or if you like, its own truth.

A most striking example is a new law passed in Poland that makes talking about the Polish nation’s part in the Holocaust a punishable crime. Since Poland itself had been occupied, it is indeed unfair to blame the Polish nation as some still do in the US or Israel, but the law is being also used as a tool to suppress any discussion of Polish participation in Holocaust.

Lipman: These days Russia’s position is barely any different. Russia is bashing its enemies with its own “history bludgeon” just like they do.

Miller: After 2014, the approach to Russia as а bogeyman, the major enemy, etc., has naturally received a new boost and new legitimacy at the international level. And in Russia, the state realized that it did not have the necessary tools to pursue its own politics of memory and proceeded to develop such instruments, among them organizations that pose as NGOs, nongovernment organizations, but, in fact, are arms of the government. They draw on state funds and solve certain problems inside Russia as well as abroad. The operation of the Historical Memory Fund is mostly focused abroad; the Military Historical Society pursues a more aggressive policy as compared to the Historical Society, but all of them play in tune.

|

“The Church is the mastermind and curator of history park exhibitions in Russia.”

|

As the state grew more actively engaged in the domestic politics of history, the situation in Russia significantly changed. Firstly, the Russian Orthodox Church emerged as a highly active, effective and successful independent player. The Church is the mastermind and curator of history park exhibitions in Russia. [See the Point & Counterpoint article, The Russian Orthodox Church’s Conquest of the History Market.] These history parks’ narrative is different from that of the government, but they are not in an irreconcilable conflict with it. Secondly, the dramatic deterioration of relations with the West has dealt a very hard blow to any pro-Western lines in Russia, in particular, at the official level. While in 2013 the Russian Foreign Ministry doctrine spoke about “Russia, a European nation,” in 2016 the Foreign Ministry doctrine no longer had such an outlook. A dramatic revision of the “politics of memory” was launched, and the new system of foreign relations draws on this new “politics of memory.”

Lipman: In recent years, the state has been involved in many spheres that it had previously left alone, “historical memory” is but one of those spheres. And yet there is no sense that the government is pursuing a “single true line” or that everyone in Russia, from first-graders to professional historians, has to adhere to a single line and not deviate from it.

|

“The current Russian politics of memory is radically different from the one that existed in the Soviet Union.”

|

Miller: This is a very significant point. It should be understood – and this is especially important for foreign readers – that the current Russian “politics of memory” is radically different from the one that existed in the Soviet Union. Back then, politics drew on a dogma and the single true doctrine. Unlike that period, today, professional historians are practically free – one can write whatever one wants. Very diverse views can be expressed in the media. What the state is concerned about is not that everyone thinks alike. The Kremlin’s concern is that Russian people at-large receive messages that follow roughly the same line. And this goal has been successfully achieved. The state does not seek to correct historians’ minds. What it seeks instead is that those historians who share the state’s vision – whether voluntarily or for the money – be granted broader opportunity in order to influence the mindset of the Russian people.

|

“The Kremlin’s concern is that Russian people at-large receive messages that follow roughly the same line.”

|

Sometimes the government’s operation is fairly subtle. The centenary of the 1917 Bolshevik revolution was a characteristic example: the government consistently stayed out of the commemoration and left the field to a broad range of authors, conferences, exhibitions, publications, etc. One could do whatever one wanted. The only thing one was not allowed to say was to blame the revolution on Jews, although there are people in Russia who are willing to believe this.

Putin, for his part, picked an indirect way to make clear what he personally thought about the Bolshevik revolution. In 2017, Putin attended the openings of three monuments. The first one was a gigantic memorial to victims of political repression. The second was a monument to his favorite Tsar, Alexander III, in Crimea. The third was the reconstruction in the Kremlin of a commemorative cross to Grand Prince Sergey Aleksandrovich who had been assassinated on that spot. The original cross was torn down by Lenin himself – that is, Lenin personally took part in its demolition – and Putin personally took part in its reconstruction. This was a symbolic demonstration of Putin’s perception of the revolution, yet his position was by no means inculcated as the official one. The revolution was broadly discussed, and, although opinions were often conflicted, those debates did not lead to a “civil memory war,” which is certainly praiseworthy.

Lipman: In conclusion, we should probably say that the main point is not the actual historical events. Any popular idea of history is selective and focuses on just a few episodes and their interpretations. Obviously, those popular ideas are very superficial. If one seeks a fight and looks for a reason for hostility, one can always find it in history. But by the same token, one can find in history a reason to reconcile.

Miller: People in Europe are well aware of the clash of the cosmopolitan and antagonistic cultures of memory. They are also aware that it no longer makes sense to pursue the cosmopolitan culture of memory the way it had taken shape in the late 20th century. This has given rise to a new interesting trend, an attempt to offer a “third way,” a new approach that would be between those two memory cultures. An “agonistic” culture in addition to the antagonistic and the cosmopolitan ones.. what’s it like? It admits that in historical memory, as in other spheres of life, there may be a clash of opinions, a conflict. Yet, unlike the antagonistic culture, the agonistic one suggests that this conflict be manifested through a dialog based on mutual respect. Today we can only talk about the agonistic memory culture as a desirable option; its examples are not easy to find in real life. Probably one can find such examples at the level of local communities.

Alexey Miller is a Russian historian. His professional interests include histories of Russia, Poland, Ukraine, empire studies, problems of historical memory, and politics of history. He has authored several monographs and numerous articles and is actively engaged in public discussions of history and historical memory and its political implications in today’s world. He is currently the director of a Russian Science Foundation grant for research on politics of memory in Russia and Eastern Europe.