(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) In the past decade, Chinese universities have been inviting mid- and senior-level military officers from Central Asia and other countries in Eurasia. Chinese military education programs are especially attractive to officers from Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, which have limited access to Russian military training. For now, Russian military education still dominates in Central Asia, but in the long term, Chinese options are likely to become more attractive. By contrast, in Eastern Europe and the South Caucasus, officers are invited to professional military education (PME) options in the United States and Europe. Western, Russian, and Chinese academies offer different perspectives on global security and war, but only the Western programs expand critical thinking skills. If they are left with only Chinese and Russian options, Central Asian military leaders will be disadvantaged in comparison to others in the post-Soviet neighborhood.

The Chinese Option in Military Education

International military education exchange programs have long been a way for regional and global powers to build lasting collaboration with other nations. Military academies create transnational networks of alumni sharing similar perspectives on global and regional security. In the long term, exchanges in military academia seek to create globally integrated operations that can easily adapt to war’s changing nature. Since the end of the Cold War, Western PME institutions have dominated, generating such networks worldwide. But in Eurasia, and especially in Central Asia, military education in Russia continues to be the most prestigious route. Military schools in Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan also admit small numbers of students from Central Asia.

Most Central Asian military leaders have a degree from a Russian military academy. Kazakhstan Defense Minister Nurlan Ermekbayev graduated from the Red Banner Military Institute[1] of the USSR Ministry of Defense in Moscow shortly before the Soviet regime collapsed. His counterparts from Kyrgyzstan, Taalaibek Omuraliev, and Tajikistan, Sherali Mirzo, graduated from the prestigious Military Academy of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Russia in the 2000s. Most mid-level security officials in these three countries have also studied in Russia at some point in their careers.

Today, Russian military academies offer three different tracks: for 1) Russian citizens, 2) students from Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) member states, and 3) the broader world. Since Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan are not members of the CSTO, their students are provided the same level of learning materials as students from Africa or other regions. This experience can be alienating for Central Asian students. Non-CSTO students lack access to higher levels of sensitive information shared between the organization’s member states, such as joint planning and operations. Accurate data is hard to come by, but Turkmenistan now sends students to the Military Academy of the Republic of Belarus for Russian language education. Another emerging problem for Russian schools has been the decreasing levels of Russian language proficiency among younger cadets from Central Asia.This cuts off new generations of students from Moscow’s perspectives on regional security, including toward the wars in Ukraine, Georgia, or Nagorno-Karabakh.

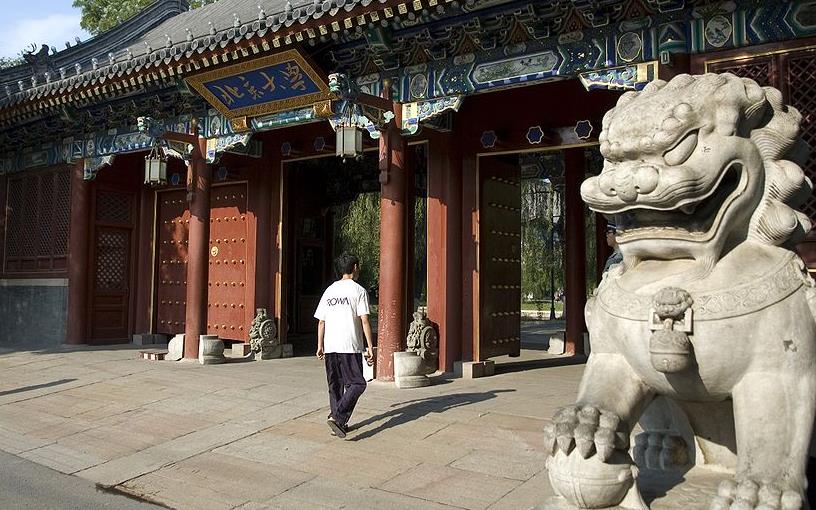

Meanwhile, over the past decade, China has been ramping up its military exchange programs. Nearly half of the 70 military academies operated in China admit foreign students. Only a few offer senior-level education. The College of Defense Studies of the PLA National Defense University (PLA NDU) is the highest level of foreign training for the Chinese People’s Liberation Army and accepts students from more than 100 partner nations, including Eurasia. The PLA NDU has pursued relationships with Latin American and African militaries. Inevitably, many of China’s partner nations also educated their senior military officers in the United States and Russia.

The PLA NDU is under the leadership of the Central Military Commission and is the only comprehensive joint command for the entire Chinese army. Its main task is to train foreign senior military officers, civilian officials, and some Chinese military officers, and it also conducts international exchanges and academic discussions on defense and security issues. In effect, the PLA NDU is part of the military diplomacy effort to boost China’s soft power alongside its global economic expansion.

Chinese civilian universities and military academies have been increasing collaboration with each other over the past decade. As part of Beijing’s military-civilian fusion policy, China’s military universities are developing ties with the private sector, especially technology firms, to ensure “that social resources are transformed into two-way interactive economic competitiveness and military combat effectiveness.” For instance, PLA NDU courses include discussions on military applications of AI technologies, something its Western and Russian counterparts may still be lacking. Along with increased PME exchanges, China seeks to portray the PLA NDU as a source of innovation and regional stability.

In the early 2000s, Beijing began to encourage Central Asian states to send their military officers to short-term courses in China. In 2014 it established the China National Institute for Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) International Exchange and Judicial Cooperation in Shanghai, which trained 300 officers from SCO countries in less than four years. As Beijing seeks to increase the enrollment of foreign students, universities have begun to actively recruit Central Asian military officers for Chinese programs. Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan now have senior military officials who have been educated in Chinese universities.

The university builds direct relations with leading military academies in Central Asia as well. The PLA NDU and the Armed Forces Academy of Uzbekistan are cooperating on educational exchanges. Some governments have carefully balanced enrollment among these three directions (Russia, China, and Western countries) to avoid tilting toward any one in particular. Chinese universities offer dozens of slots for students from Uzbekistan, but Tashkent only takes one-third of them. Students and staff of the Military-Technical Institute of the National Guard of Uzbekistan take Chinese-language classes to build proficiency in case they have an opportunity to study in China.

Although Beijing prioritizes building strong relations across the entire Asian region, Central Asian countries account for only a fraction of all military exchange interactions. Nevertheless, with China’s growing economic and security presence in the region, Chinese institutions may soon become as prestigious—if not more prestigious—than Russian academies. In recent times, the PLA NDU has offered higher stipends to students than Russian schools and allows more significant exposure to Chinese technological and scientific innovations.

Different Approaches

Western, Chinese, and Russian PME schools all provide a foundation in political science and security studies. But they differ in pedagogical methods and interpretations of international security. Russian and Chinese military schools examine security problems in depth but rarely consider their root causes. The curriculum skims military ethics and human rights. At the PLA NDU, for example, no student—Chinese or international—can criticize Beijing’s military operations or treatment of Muslim minorities. In contrast, PME programs in the United States encourage policy critiques and active classroom debate. U.S. military academic curriculum reflects general debates within academia and national political developments. For instance, in his commencement address at NDU in July 2020, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley apologized for accompanying President Donald Trump’s walk across Lafayette Square for a photo op after Black Lives Matter protesters were violently cleared away, saying that it “created a perception of the military involved in domestic politics.”

Graduates of Russian, Chinese, and Western military academies point out that although each host country openly seeks to advance its own strategies and operations in response to global security challenges, Russian institutions focus on the Kremlin’s vision of regional and global security and hybrid warfare. For its part, the PLA NDU’s curriculum is built on Sun Tzu’s ancient The Art of War, Confucius studies, and the theory of three warfares (public opinion, psychological, and legal). In Western PME schools, students study theories of war and morality according to Thucydides, Clausewitz, and other Western luminaries. The U.S. PME curriculum is also widely guided by the U.S. National Defense Strategy.

Furthermore, the greater separation between native and foreign students in both Chinese and Russian military universities limits opportunities for shared academic experiences. Due to Mandarin-language barriers among most foreign students, the PLA NDU offers courses in foreign languages, including in English, French, Russian, and so forth. According to Central Asian students who have studied in both U.S. military academies and at the PLA NDU, the main difference is the imaginary wall separating Chinese and international students—they rarely interact.

In contrast, Western PME institutions emphasize high collaboration between U.S. and international officers. According to a May 2020 “new vision” document published by the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, America’s growing military diplomacy is part of a larger goal of “Developing Today’s Joint Officers for Tomorrow’s Ways of War” and to “develop judgment, analysis, and problem-solving skills, which can then be applied to contemporary challenges.” The National Defense University in Washington, D.C., for instance, states its mission as educating “joint Warfighters in critical thinking and the creative application of military power to inform national strategy and globally integrated operations, under conditions of disruptive change, in order to conduct war.” As described by the university, its Chinese counterpart relies on “form over substance, top-down management, tight control of political messages, and protection of information about PLA capabilities.”

To date, the United States has hosted over 13,000 Central Asian military and civilian officers as part of numerous programs: International Military Education and Training (IMET) program, Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Germany, Foreign Military Financing (FMF), Combating Terrorism Fellowship Program (CTFP), International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement, and Section 1004 Counter-Drug Assistance. The IMET programs offer short, certificate-level courses and graduate programs across U.S. senior service institutions. They focus on partnership building, decision-making, strategic and critical thinking, and interoperability.

Washington has also recently increased the frequency of special forces training with Central Asian militaries. Hundreds of troops are trained annually in each country, adding up to over 1,000 U.S.-trained troops across the region. Furthermore, U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) and NATO forces hold annual Steppe Eagle exercises with Kazakhstan to enhance interoperability and peace support operations. In 2019, CENTCOM conducted joint military exercises in Tajikistan with Mongolia and Uzbekistan. Joint special-forces trainings were expanded under the Obama administration and continued at the same level under the Trump administration.

Still, an important distinction between U.S. initiatives in Central Asia and military education exchanges with Russia and China remains: short-term courses are just that—short. Longer programs are more successful in building long-term relationships between international officers, creating mutually shared experiences, and imparting a common body of academic thinking about security issues. Graduate-level education for senior officers may have a more immediate impact on building ties than exchanges involving junior officers.

Even in short-term course offerings, China may be gaining momentum. According to a report from the China Social Science Net, the PLA NDU has held annual international security seminars since 2002 to expand academic research exchanges with the international military community. The seminars aim at strengthening military exchanges, developing cooperation with countries around the world, and imparting a common approach to issues. It has received students from more than 90 countries, more than 1,300 delegations, and more than 12,000 foreign military and government officials, experts, and scholars. The PLA NDU maintains regular contacts with higher military academies in more than ten countries and has contacts with more than 140 countries’ militaries. In Central Asia, China has been participating in bilateral and multilateral military drills since the early 2000s.

While the influence of Chinese military academies is not as widespread in Central Asia as in other parts of the world, in the coming years, it may have more significant impact on the composition of military leadership compared to other countries in Eurasia. For example, Kazakhstan’s top defense leaders were educated entirely in Kazakhstani, Russian, Ukrainian, or Soviet (in Russia) institutions. Not one deputy minister or others in themilitaryleadership holds a Western degree. Most senior defense officials in Georgia, by contrast, have a traditional academic or PME degree from a Western institution. Furthermore, some top Ukrainian defense officials have been educated in Western programs—Defense Minister Andrii Taran has a master’s degree from the National Defense University in Washington. In short, unlike countries in the South Caucasus and Eastern Europe, Central Asian countries have lacked the same access to Western education, leading them to fall under increased Chinese military education influences.

Conclusions

PME exchanges are long-term commitments to international interoperability and alliance building. It takes years and multiple interactions to build transnational networks that would foster a similar understanding of security issues and allow interoperability. Chinese military education exposes Central Asian officers to a broad range of perspectives, undercuts Russian dominance in military education, and competes head-on with Western short-term programs. Western PME institutions need to pay attention to Chinese universities’ expanding recruitment efforts to offer opportunities that neither Russian nor Chinese counterparts can match. Namely, critical and academic approaches to understanding security by discovering the root causes of security problems, open-ended discussions, and academic liberties. More Central Asian military and security officers should be invited to U.S. and European PME institutions, building and adding value to regional alliances with Central Asian counterparts.

Erica Marat is Associate Professor at the College of International Security Affairs of the National Defense University in Washington, D.C. The opinions implied here are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of the National Defense University, the Defense Department, or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

[1] Official name: Военный Краснознамённый институт Министерства обороны СССР.