(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) How have citizens’ attitudes about the state and its capacity to deliver public goods changed during an especially fraught period caused by the COVID-19 pandemic? This memo focuses on the experiences of three post-Soviet countries (Estonia, Georgia, and Ukraine), exploring how trust in and satisfaction with the state have changed since the beginning of the pandemic and the potential implications for legitimacy and geopolitical stability going forward. Concerns relating to the possible destabilizing effects of this pandemic are especially acute in at-risk countries bordering antagonistic neighbors, where the threat of regional conflict is high; all three of our case studies are in that category, having experienced kinetic and/or cyberattacks from the neighboring Russian Federation. Presented here are evaluations of state capacity over 2020-2021 via COVID-focused surveys, which indicate that citizens’ views about faith in institutions rise and fall with citizens’ respective government’s ability to manage crises. Such changes in public viewpoints create potentially actionable inroads of political maneuvering by influential powers.

Appraising Governmental Deliverables

States cannot successfully function in the long term if they lack legitimacy, or the consent of the governed, and such consent is to a large degree incumbent upon the delivery of the elements of human security (such as healthcare, education, a livable income, and the ability to participate in the electoral process) via what is generally known as state capacity. The concept of state capacity is traditionally subdivided into categories, including coercive, extractive, and bureaucratic. While the names of these subtypes sometimes vary, the categorization is generally consistent. Coercive state capacity encompasses the ability of the state to defend itself from external and internal threats and includes actors such as the military and law enforcement. Extractive state capacity covers the ability to generate revenue and includes tax authorities. Our concern here is with bureaucratic state capacity, which encompasses the provision of human security.

The Central Eurasian State Capacity Initiative (CESCI), funded by the Office of Naval Research through the Minerva Research Initiative, has been evaluating state capacity, resilience/stability, and legitimacy since its launch in 2019, focusing on the experiences of Estonia, Georgia, and Ukraine. To probe how effectively these vulnerable governments have been in bolstering human security during the pandemic, CESCI conducted COVID-focused surveys (PACE) and included questions on omnibus surveys conducted by local survey organizations in the three target countries. The surveys include questions about trust in and satisfaction with selected institutions and organizations that provide different forms of state capacity. The surveys discussed in this memo were conducted in spring 2020, spring 2021, and summer/early fall 2021.

The surveys provide valuable insights into public views about the state, but the responses must be interpreted in perspective and, in some instances, with caution. First, national-level metrics from a variety of sources show how our three countries rank consistently from highest (Estonia) to middle range (Georgia) to low (Ukraine) in terms of human development and governmental effectiveness. For example, the widely-cited Human Development Index and the Worldwide Governance Indicators both position our cases in that order. Baseline levels of trust and confidence vary across countries and across state actors in roughly that same order.

Some differences in the wording of our survey questions between the PACE surveys and the omnibus surveys also require a nuanced interpretation of the results. The questions about trust were consistent across all of the surveys. We asked: “For each of the items below, please tell me on a scale of 1-5 how much you personally trust each of the institutions, where 1 means very low or no trust and 5 means complete trust.” However, our questions about satisfaction varied. In our PACE survey, we asked respondents, “How would you rate the job each of the following is doing responding to the Coronavirus pandemic?” on a 1-5 scale. In the omnibus surveys, we did not specifically identify pandemic performance and modified the questions to read, “For each of the items below, please tell me on a scale of 1-5 how satisfied you are with the performance of each of the institutions where 1 means not satisfied and 5 means completely satisfied.”

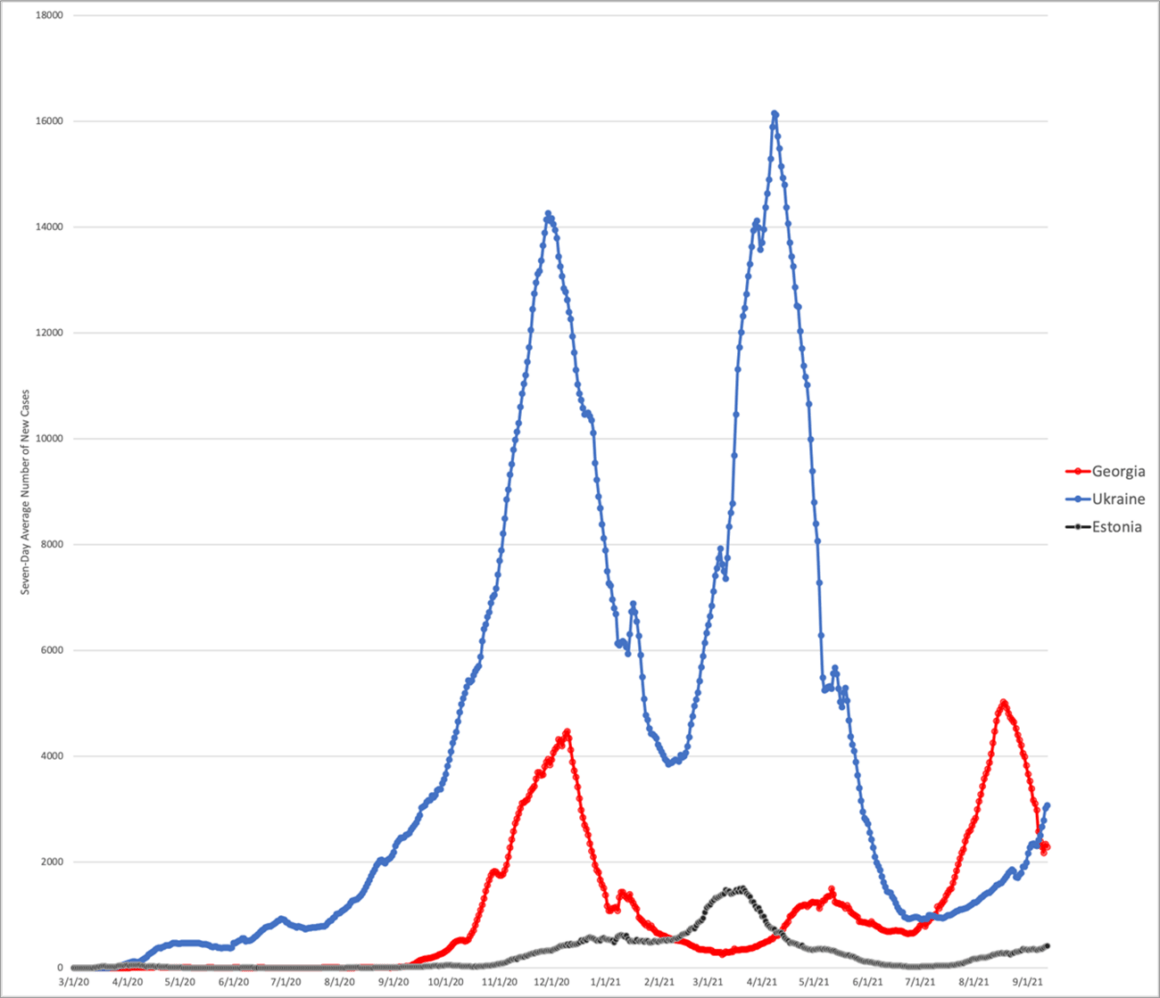

Further, cross-national comparisons of government responses to COVID-19 must take into account the fact that, as shown in Figure 1, each country experienced waves of the pandemic at different times and at different levels of severity, so citizen trust and/or satisfaction with the state could be directly influenced by conditions on the ground at the time the surveys were conducted. Indeed, the three countries differed slightly in the timing of the pandemic’s onset, with Ukraine experiencing a significant upturn in cases in late summer 2020, Georgia in late fall of that year, and Estonia commencing a sustained upward infection trajectory in the early months of 2021. Ukraine and Georgia subsequently were hit by even higher second peaks.

On-the-ground conditions are likely to have influenced respondent perceptions of institutional performance, even if the questions are not framed around pandemic responsiveness. The PACE surveys predate major COVID-19 outbreaks and serve as a good baseline. The first set of omnibus surveys was fielded immediately after Estonia’s highest peak outbreak; after Ukraine’s initial spike and as its second (and highest) outbreak was occurring; and after Georgia had experienced its first peak, making these responses relevant to immediate, almost real-time concerns about the virus’s impact. The second set of omnibus surveys captures the period after each country had experienced a major surge in reported cases (for Ukraine two such events) and before Georgia’s second spike, serving as a data point for populations that had emerged from a major outbreak.

Figure 1: New Cases of COVID-19, 7-Day Moving Average

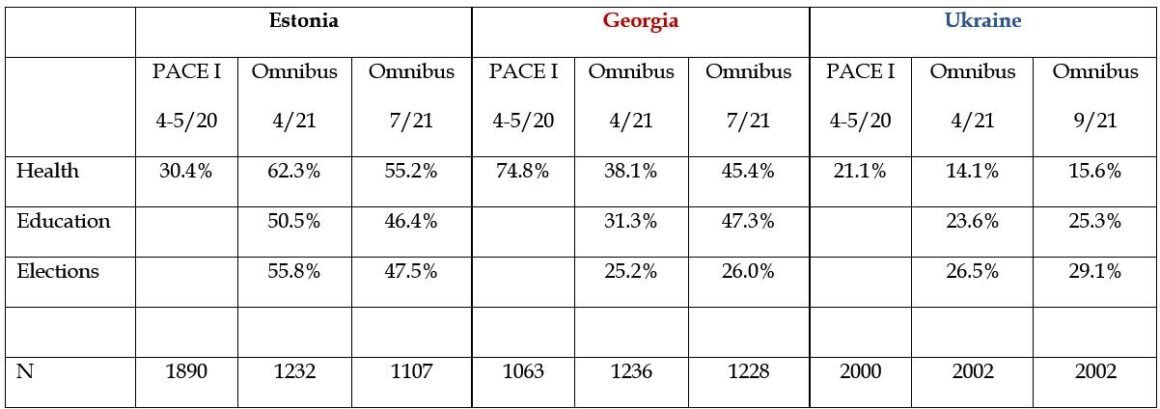

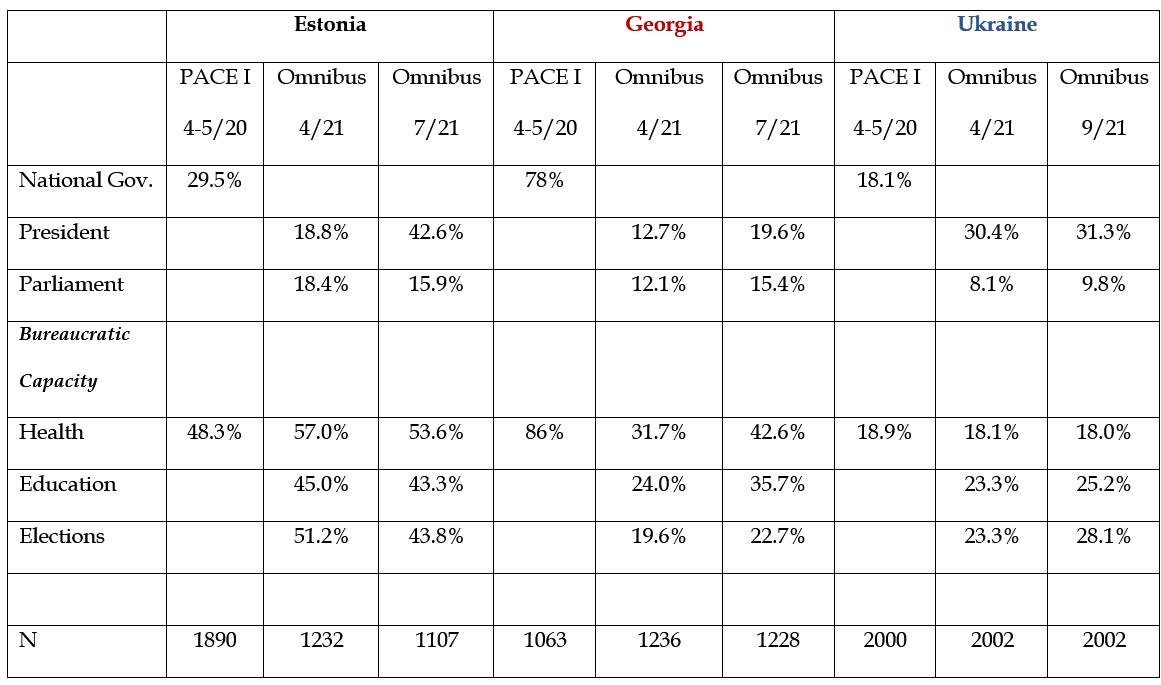

With these caveats in mind, to what extent do trust and confidence in the state vary across countries, among different forms of bureaucratic state capacity, and over time during the pandemic? Table 1 presents responses to the level of trust in institutions among the cases, with responses regarding satisfaction with the performance of the same institutions detailed in Table 2.

Table 1: Trust in Selected Bureaucratic Capacity

Table 2: Satisfaction with Selected Institutions

Estonians report higher levels of both trust and satisfaction in government than respondents in Georgia and Ukraine, while Ukrainian respondents consistently report the lowest levels of both trust and satisfaction among the three countries. While it is perhaps a reasonable generalization to rank the countries from the most trusting/satisfied (Estonia) to the least trusting/satisfied (Ukraine), with Georgia situated in the middle, rank-ordering is not perfectly consistent across all responses items or across all surveys.

Among agencies that generate bureaucratic state capacity, perceptions of education and elections are generally stable within each of the countries. However, attitudes about healthcare are not stable, and this particular pattern is likely associated with the effects of COVID-19. In the early stages of the pandemic, Estonian respondents’ trust in and satisfaction with the health system was relatively low. While it did not reach the nadir of Ukraine, a lower percentage of Estonian respondents trusted/were satisfied with healthcare than respondents in Georgia. This is probably because of an early (March 2020) modest outbreak in Estonia that precipitated the advent of unpopular quarantine conditions. In this specific context, public dissatisfaction is not surprising. In an analogous way, Georgian attitudes are more positive during the PACE survey—prior to its initial wave—than in later surveys after the pandemic had struck with a vengeance and attitudes about the efficacy of the Georgian health care system had deteriorated.

Ukraine is in a class of its own when it comes to citizen attitudes about governance and state capacity delivery. Although there are slight declines in both trust and satisfaction as the pandemic spread and intensified, the takeaway from our survey responses is that COVID-19 made a bad healthcare situation worse. This is in keeping with other surveys that have long demonstrated the negative attitudes that Ukrainians hold about their government, including the 2019 Gallup poll that found that Ukraine had the lowest level of confidence in government in the world, and a 2020 survey that showed trust in state agencies in that country is low and declining.

While limited in time and scope, our survey responses suggest several implications regarding citizen attitudes about the state during a societal crisis. The fragility of trust and satisfaction in institutions is also evidenced by temporal variation in attitudes about healthcare. Estonian respondents were more negative about the healthcare system in the early stages of the pandemic, whereas Georgians were more positive in early 2020. But data from 2021 suggest a reversal in attitudes, with Estonia’s health institutions enjoying stronger trust and satisfaction than Georgia’s. This change in attitudes coincides with changing conditions on the ground; Estonia experienced an early outbreak and then stabilized, while Georgia delayed the virus’s initial progress and suffered enormously when the contagion struck with full force.

Not unexpectedly, given its higher human development rankings, Estonia has made more extensive progress in disease mitigation and vaccine distribution than the other two countries discussed here, results that are evident in data on COVID mortality and vaccination rates. At the time of writing, Estonia manifests around 115 coronavirus deaths per 100,000 population, whereas Ukraine is at 162, and Georgia is at an extremely high 270. Both Georgia and Ukraine are currently experiencing a concerning third wave of coronavirus infection, which adds yet more cases and deaths. It is too early to draw a confident causal connection to the changes in attitude in either a positive or negative direction, but trust in and satisfaction with healthcare tracks with the course of the disease in our subject countries.

What Lessons Can Policymakers Take from These Data?

While the analysis is preliminary, the data suggest that attitudes about trust in and satisfaction with institutions fluctuate with their ability to manage crises. In terms of geopolitical stability, this creates opportunities for hostile neighbors to undermine institutions—especially weak ones—by exacerbating crisis situations.

Across the globe, the recent spread of disinformation via social networks and the challenges of COVID-19 pandemic management challenge governments and elevate concerns about the ability of states to maintain legitimacy. Actions that build public confidence in institutions are critical, especially in light of new revelations from the Pandora Papers about questionable actions by prominent politicians in Georgia and Ukraine that are likely to further degrade perceptions of legitimacy. In the short term, international assistance with investments in healthcare infrastructure is particularly needed in Georgia and Ukraine, which have lagged far behind Estonia in vaccinations. As the CESCI research team noted in an earlier publication, if the elements of human security are lacking or deteriorating, sovereignty might be at stake, especially if countries, such as Estonia, Georgia, and Ukraine, are situated in a geopolitically vulnerable position and subject to direct military threats from the Russian Federation.

Ralph Clem is Professor Emeritus of Geography and Senior Fellow at the Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs at Florida International University.

Erik Herron is the Eberly Family Distinguished Professor of Political Science at West Virginia University.

The research for this memo was supported by a U.S. Department of Defense Minerva Research Initiative Grant (Office of Naval Research; N00014-19-1-2456).

PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 729