(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) Democratic transitions initially tend to bring about higher levels of political corruption. This is well documented globally, and most post-Soviet states are no exception. Increased political corruption, or the use of public office for private gain, is a discouraging reality for local activists and international organizations promoting democracy. Citizens of states where full democracy is not achieved—a common occurrence nowadays—must live with greater corruption indefinitely, often souring their views on democracy. The good news is that bolstering legislative and judicial constraints early in the democratic transition can minimize increases in corruption. This is evident by comparing democratic transitions in Estonia, Kazakhstan, and Armenia. The importance of legislative and judicial constraints to curtailing corruption is also demonstrated with global data in an article that colleagues and I published.

Why Legislative and Judicial Constraints Are Most Helpful

Democratic transitions—extraction from the former regime and the introduction of civil liberties and competitive elections—can bring about many changes in institutions and rights, whether they ultimately succeed in producing full democracy or not. Of these changes, legislative and judicial constraints on the executive are most useful in abating corruption. Let’s first examine the logic of this.

A legislature constrains the executive when its members can question, challenge, and investigate the executive. A judiciary constrains the executive when lower and higher courts are independent, and the judiciary can ensure the executive complies with courts’ decisions and the constitution. These constraints are more effective than other institutions and rights at minimizing corruption that comes with a democratic transition because they hinder the initiation of corruption schemes. A single corrupt act typically involves officials from different government offices. When legislative and judicial constraints on the executive exist, members of parliament and judges themselves adhere to the law, making it more difficult for the executive to convince them to engage in corruption and thus hindering illicit schemes.

By contrast, other changes that accompany democratic transitions tend to facilitate corruption. The initial expansion of freedoms of expression and association makes it easier to engage in corruption. Less restricted communications and greater transparency about government operations enable officials, bureaucrats, and citizens to more readily identify opportunities and collaborators for corruption. An end to the social atomization of the nondemocratic era makes it easier for potential collaborators to interact and hatch corruption schemes.

Only when the freedoms of expression and association are very strong does their power to hold government officials accountable outweigh their tendency to facilitate corruption. A high level of freedom of expression allows media outlets to investigate possible corruption and provides citizens with the information necessary to punish corrupt officials. A high level of freedom of association enables collective action in response to information about political corruption. These accountability mechanisms, in turn, deter government officials from engaging in corruption. Freedoms of expression and association must reach very high levels to curtail corruption, whereas even growing judicial and legislative constraints on the executive begin to have a positive impact. Now, let us examine how this unfolded in three post-Soviet states.

Varied Levels of Constraints in Estonia, Kazakhstan, and Armenia

The different experiences of Estonia, Kazakhstan, and Armenia demonstrate the impact of legislative and judicial constraints on corruption. Estonia significantly strengthened constraints, and the level of corruption dropped. Kazakhstan did not, and corruption grew. Armenia experienced each scenario—minimal constraints at the time of independence and significant constraints at the time of the 2018 revolution—and corruption levels increased and decreased, respectively. For all three states, the story begins in the late 1980s, when these territories were republics in the Soviet Union.

Estonia

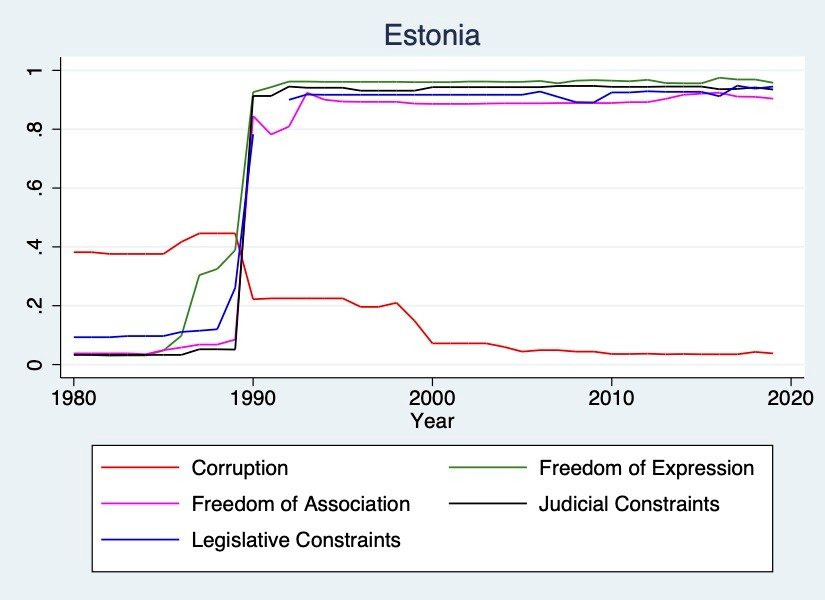

Legislative and judicial constraints emerged early and not only minimized but actually reduced corruption in Estonia. The March 1990s elections to the republic’s Supreme Soviet were relatively free, meaning that its new members were accountable to voters, rather than just the “executive,” in this case the Communist Party. This accountability empowered members of the Supreme Soviet to act as a check on the executive. The constitution of newly independent Estonia, adopted in 1992, further strengthened legislative constraints on the executive. The constitution mandates free and fair elections for Estonia’s parliament, the Riigikogu, thus continuing the body’s accountability to voters and its role as a check on the executive. The constitution gives members of the Riigikogu the right to question government ministers: the prime minister and other ministers must regularly attend parliamentary sessions in order to answer legislators’ questions about the executive branch’s actions. The Riigikogu also has the right to force any minister, the prime pinister, or the entire government to resign through a vote of no confidence. Accountable to voters and independent of the executive branch, members of the Riigikogu have used these measures to constrain the executive. The strengthening of legislative constraints with Estonia’s democratic opening is evident from the blue line in Figure 1.[1] The break in the line reflects the transition between the Supreme Soviet and Riigikogu.

Figure 1. Constraints, Freedoms, and Corruption: Estonia

In its early years, Estonia’s freely elected legislature also strengthened judicial constraints on the executive, depicted with the black line in Figure 1. The legislature passed the Courts Act and the Legal Status of Judges Act in 1991, which, along with the new constitution, empowered the judiciary to act as a check on the executive. These measures created independent lower and higher courts and helped ensure that the executive complies with courts’ decisions and the constitution. They did so by mandating that judges be appointed for life, restricting executive activities that could influence court decisions, and granting constitutional review authority to Estonia’s Supreme Court, according to Estonian legal scholar Jaan Ginter. Estonia has also established a public prosecutor’s office independent of the executive, and this office has been effective in prosecuting corrupt officials.

The significant legislative and judicial constraints Estonia imposed on its executive branch not only prevented an increase in corruption but also helped reduce corruption from the Soviet era, as is evident from the red line in Figure 1. The initial small increase in freedom of expression contributed to an initial bump in corruption, as corruption schemes became easier to plan. But, the then-high levels of freedom of expression and association that Estonia quickly reached helped reduce corruption. (See the green and purple lines in Figure 1.) They enable citizens, media, and civic groups to hold government officials accountable for corruption, which also deters government officials from engaging in illicit activities.

Kazakhstan

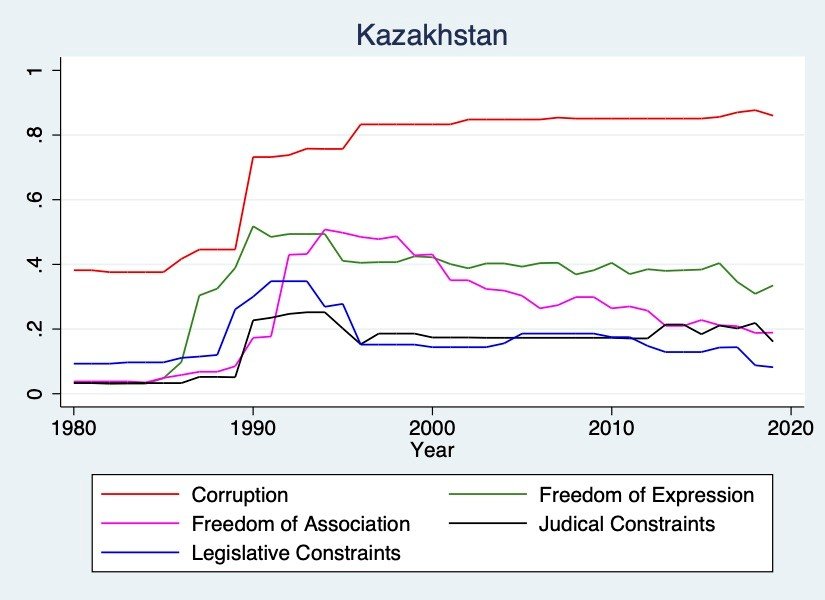

Unlike Estonia’s parliament, Kazakhstan’s has not served as a check on the executive or created effective judicial constraints on the executive. The Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic also experienced more competitive elections to its Supreme Soviet in March 1990 than it had in the past. From that point, however, the state’s path diverged from Estonia’s. Kazakhstan’s first elections to its parliament, the Supreme Kenges, in 1994 were not free and fair. Election authorities disqualified numerous opposition candidates, and a quarter of the seats were essentially appointed by the president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, according to a report by the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe. Due to the nature of their selection, most members of parliament were beholden to Nazarbayev rather than the voters. Consequently, legislators did not exercise their rights to constrain the executive. The new constitution, adopted in 1995, further impeded legislative constraints on the executive. It undercut any balance of power by shifting authority to the executive. The new constitution gave the president the right to dissolve the parliament for multiple reasons, including when it does not approve the president’s nomination for prime minister. The development of only minimal legislative constraints on the executive in the late Soviet era and their erosion beginning with the 1994 elections are depicted with the blue line in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Constraints, Freedoms, and Corruption: Kazakhstan

Loyal to the president, members of the Supreme Kenges did not establish judicial constraints on the executive, as their counterparts in Estonia did. In fact, the distinction between the judicial and executive branches is murky in Kazakhstan. Prosecutors, who are members of the executive, have judicial privileges, including the right to delay sentences in favor of probation, according to a human rights report. Kazakhstan’s weak judicial constraints are evident from the black line in Figure 2.

Because strong legislative and judicial constraints on the executive have not developed in Kazakhstan, corruption increased with the democratic opening in the late Soviet era and has remained high. This is depicted with the red line in Figure 2. Low levels of freedom of expression and association, evident from lines green and purple in Figure 2, facilitate corruption schemes: they are not strong enough to hold government officials accountable for or deter them from illicit activities.

Armenia

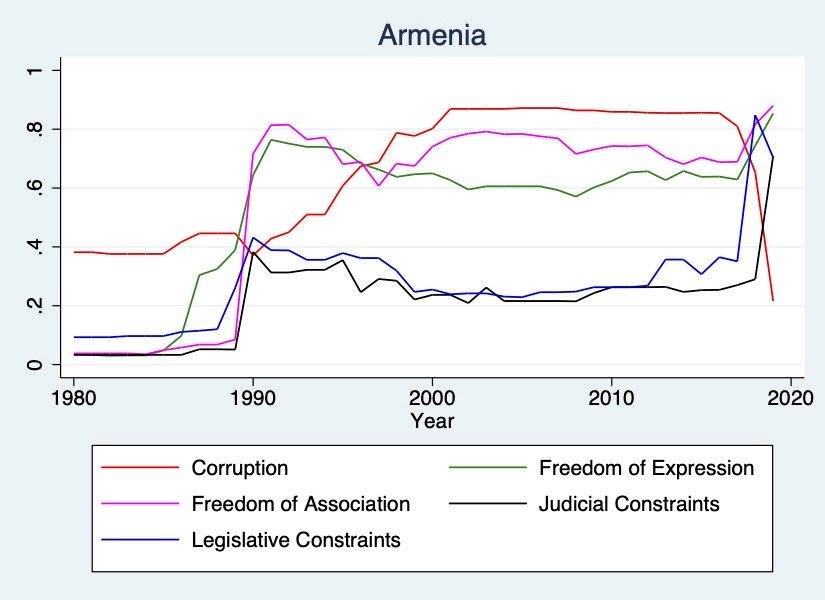

As in Estonia and Kazakhstan, the spring 1990 elections to the Supreme Soviet of Armenia established a body that was more independent of the Communist Party and thus had some ability to constrain the executive. While the climate of political liberalization enabled judges a bit more autonomy, no significant reforms to the judiciary were undertaken. The minimal legislative and judicial constraints were not sufficient to prevent President Levon Ter-Petrosyan from consolidating power and eroding these constraints, as Nazarbayev did in Kazakhstan. (See blue and black lines on the left half of Figure 3.) His government banned the main opposition party and interfered with elections to the new Armenian National Assembly in 1995 so that they were not free and fair. Without free and fair elections, members of parliament were not accountable to voters and did not effectively constrain the executive. The judiciary also did not constrain the executive during this period. The new constitution, adopted in 1995, codified executive control over the judiciary rather than establishing judicial independence. The president was head of the body that approved most of the candidates for judgeships, according to Armenian legal advisor Grigor Mouradian. With neither significant legislative nor executive constraints on the executive, corruption steadily grew, reaching a high level in 2000 and lingering there, as is evident from the red line in Figure 3. Having only moderate levels of free expression and association, as depicted by the green and purple lines in Figure 3, also fueled the corruption. Moderate levels facilitated the hatching and execution of corruption schemes but did not empower media and civil society organizations sufficiently to constrain the executive.

Figure 3. Constraints, Freedoms, and Corruption: Armenia

Change began, however, nearly 20 years later. The quality of the 2017 parliamentary elections improved as a result of a new electoral code, according to a report from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. With a more freely and fairly elected parliament, legislators began to constrain the executive. In February 2018, they adopted a new judicial code that created judicial constraints on the executive. The code establishes the independence of the judiciary from the executive and requires judges to report any attempted interference with their work.

The National Assembly took the most drastic measures against the executive as part of the Armenian Revolution, which began with protests in March 2018. Member of parliament Nikol Pashinyan became a leader of the protests, which rejected President Serzh Sargsyan’s efforts to extend his rule by becoming prime minister. These protests emboldened other members of the National Assembly to support Pashinyan and ultimately select him as prime minister. This revolutionary activity further established the National Assembly as a more independent body capable of checking the executive. Following the strengthening of these legislative and judicial constraints on the executive, the level of corruption has dropped dramatically in Armenia. The right side of Figure 3 depicts these trends.

Armenia’s experience shows the benefit of establishing strong legislative and judicial constraints on the executive at the beginning of a democratic opening. It also demonstrates that moderate levels of freedom of expression and association are not sufficient to hold government officials accountable and thus reduce corruption. As the green and purple lines in Figure 3 show, these freedoms remained at moderate levels in Armenia from the late Soviet era until the revolution. Because these freedoms now approach the highest possible levels, they too will help hold government officials accountable and curtail corruption.

Conclusion

In abating corruption that accompanies democratic openings, Estonia since 1990 and Armenia since 2018 are success stories, whereas Kazakhstan is not. Estonia’s and Armenia’s experiences demonstrate that even with initial democratic transition, people do not have to suffer higher levels of corruption. The key is to introduce legislative and judicial constraints on the executive as an early step in the transition. Economic and cultural factors also influence corruption levels in states, but these political institutions can have a significant impact on curtailing the corruption accompanying democratic openings.

Kelly McMann is Professor in the Department of Political Science and Director of International Studies at Case Western Reserve University, and Project Manager for Subnational Governments at Varieties of Democracy. The author thanks Faheem Ali for his research assistance.

[1] All figures use the indicators Legislative Constraints on the Executive Index, Judicial Constraints on the Executive Index, Political Corruption Index, Freedom of Expression and Alternative Sources of Information Index, and Freedom of Association Thick Index from the Varieties of Democracy dataset, v. 10.

PONARS Eurasia Policy memo No. 734