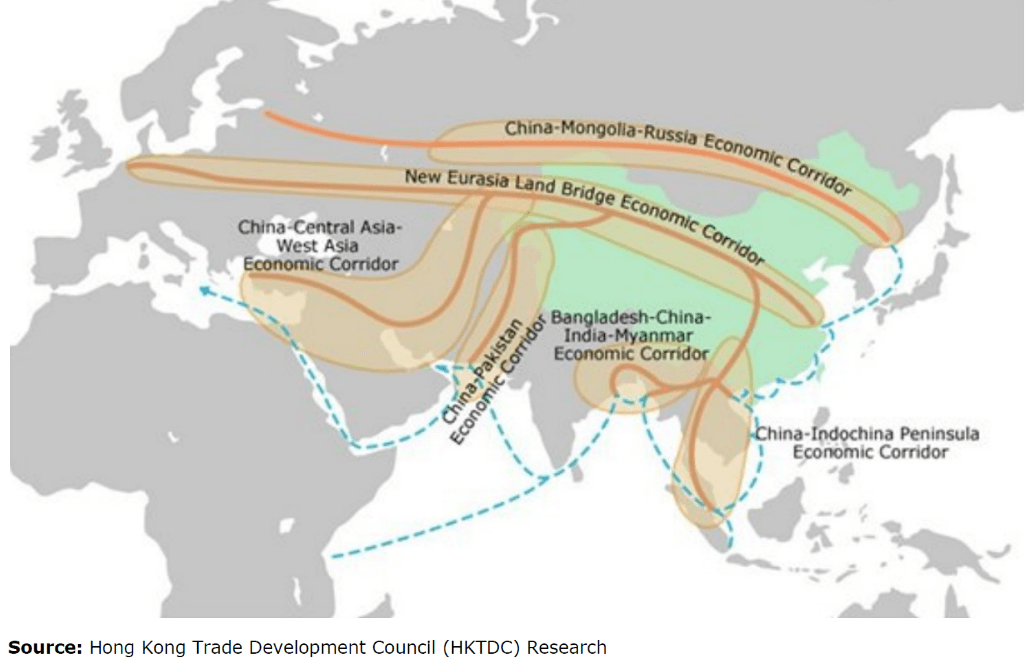

(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) First and foremost, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a $550 billion project designed to relieve China’s industrialized zones of surplus output and grow its less developed Western regions. Yet, its strategic and political-economic effects make it a geopolitical event. Strategic because the initiative forges powerful new foreign policy tools for China, for example: logistical control of trade routes (see Figure 1), an internationalizing yuan, leverage in debt resolution, and diversification of energy sources. Political-economic because the project’s scale and open-access structure will shape European and Eurasian growth. As it absorbs some countries and not others, the BRI will create its own political economy of integration and divergence.

In Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), the cases of Hungary and Serbia offer contrasting early experiences of the BRI’s geopolitical effects. Argued here is that their different transitions from communism help explain the contrast. Hungary embraced market reform earlier and more completely than Serbia and those reforms integrated its manufacturing industry into European supply chains. That enabled its rise as a high value-added intermediary to Chinese flows, buffered from the strategic and political economic influence of the BRI by Single Market membership. By contrast, Serbia’s entry into European supply chains and institutions was constrained by limited reform. This has shaped its role as a low value-added transit economy with weaker institutional leverage and worse terms of trade. The contrast between Hungary’s BRI-illiance and Serbia’s BRI-ittleness captures a tectonic shift in Europe: a new rule-maker economy challenging the EU’s competitiveness and the attractiveness of its accession policy.

Figure 1: The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Taps Europe

Hungary: Bitter at the Root, Sweet at the Fruit

The Hungarian transition can broadly be described as integration through reform. In the years around 1990, Hungarian leaders initiated major structural changes to the planned economy. In 1993-94, they responded to debt and inflation pressures with a thorough program of privatization. This transition allowed Hungary to lead the CEE region’s integration into Northern European manufacturing value chains. This integration determined the favorable terms according which Hungary now engages with China.

Hungary began its rapid climb up the value chain soon after the Antall government tackled the debt and inflation pressures of 1993-94. A highly effective program of macroeconomic stabilization and privatization saw the private sector rise from 20 percent in 1990 to 80 percent of GDP in 1998. Key to this success was a track record—growing since 1990 but with important historical antecedents—of gradual structural reforms: firming up property rights; loosening control of state-owned enterprise (SOEs); strengthening bankruptcy and supervision frameworks; decentralizing wage-setting and bargaining; and supporting labor mobility. By the mid-1990s, Hungary accounted for half of the capital inflows to the CEE region.

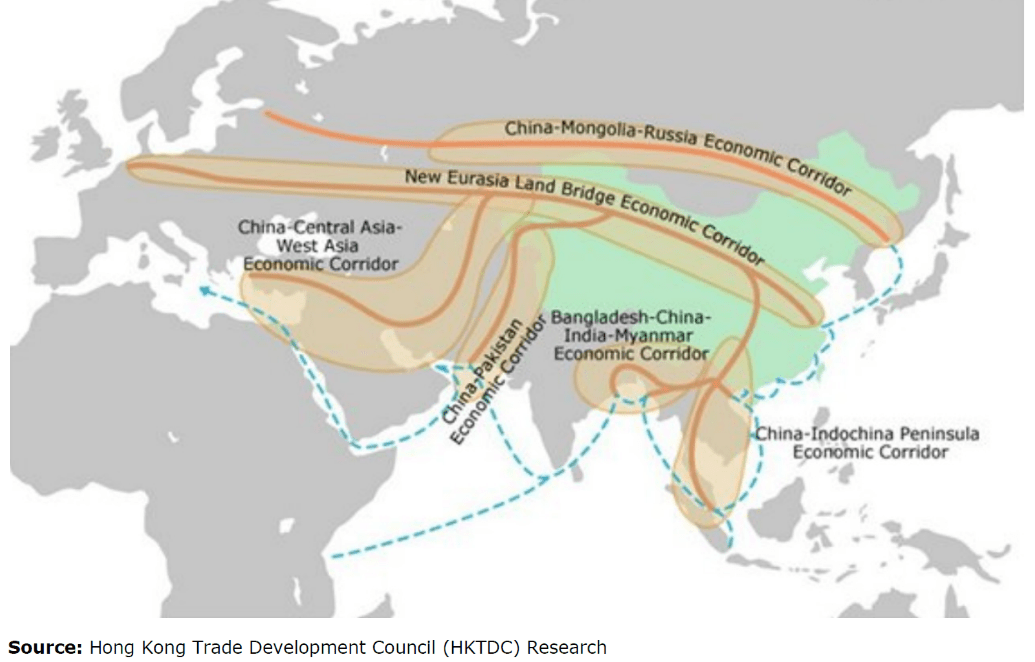

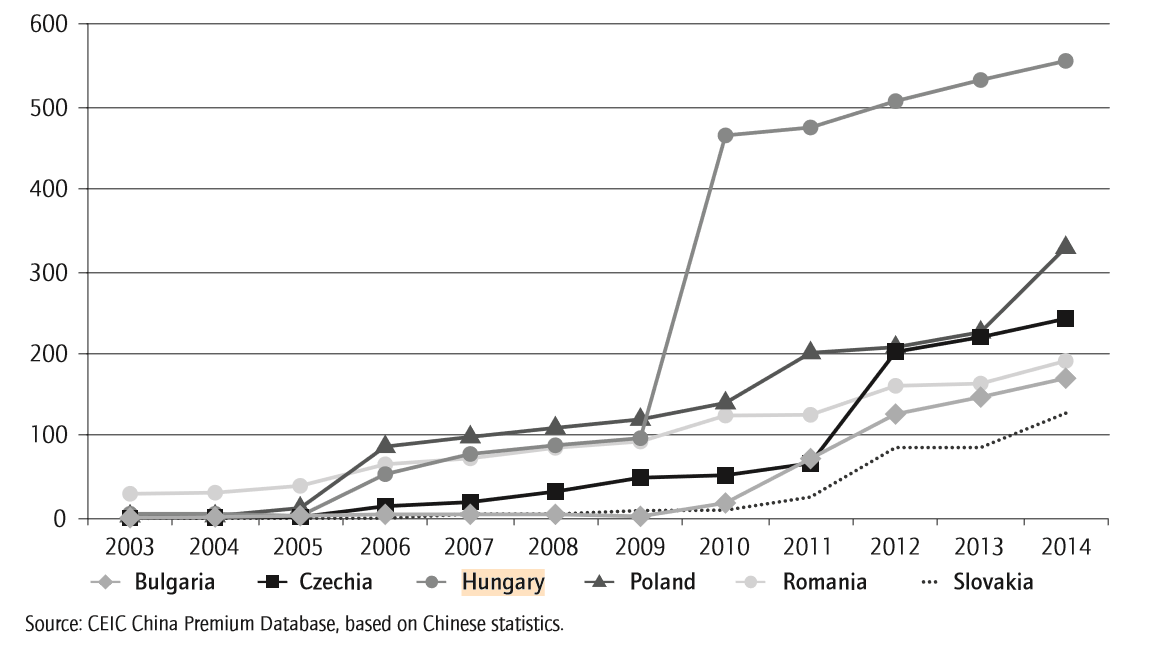

As part of this success, Hungarian firms lead the CEE region’s incorporation into Northern European manufacturing production lines (see Figure 2). German, Austrian, and Northern Italian manufacturers roamed Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Poland (the C4) for opportunities to offshore core factory production. Hot on the heels of production integration came credit, new technology, standard-setting EU-wide industry associations, the Commission’s facility for regulating common health and safety, and the EU’s social welfare norms. This regional integration was the original platform from which Hungary engaged Chinese trade. Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) into Hungary rose distinctively from a low base upon its accession to the European Union in 2004.

Figure 2: Hungary’s Integration into German Value Chains

Source: “Hungary: Trade in Value Added Database,” OECD, 2015

The Budapest government was accordingly first among the CEE states to make the cultivation of bilateral ties with China a strategic priority. It put Chinese relationships at the center of its foreign policy in 2011 as part of a wider strategy of the incumbent Orbán government to rebuild Eastward relations and reduce economic and political dependence on Western Europe. This strategic pivot has been followed over time by an array of cultural and political symbolism and an active and successful effort by the Hungarian government to draw Chinese FDI (see Figure 3).

Symbols notwithstanding, a decomposition of Sino-Hungarian trade shows the crucial role of the European Single Market in attracting and determining the content of Chinese flows. Bilateral trade is mainly intra-industry, suggesting the preponderance of value-chain interests. The factory acquired by a leading Chinese auto-parts manufacturer (Yanfeng) supplies German and Italian car brands. Huawei operates in European manufacturing and logistical hubs from Hungary, with factories, warehouses and a logistical headquarters that supply the European market with its products. Moreover, a cursory analysis of inputs from China and outputs to Germany supports this relationship. Most Chinese exports to Hungary are basic electrical components and most Hungarian exports to Germany are high-tech intermediate electronic inputs. In short, local factories and workers add—and therefore earn—high value to Chinese inputs and investment flowing through Hungary into the Single Market.

Figure 3: Hungary’s Absorption of Chinese FDI

The Single Market in turn shapes the strategic limits of this lucrative bilateral relationship. The oft-raised question of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s support of China’s foreign policy in the Council (for instance on the South China Sea) illustrates this. Hungarian divergence from Brussels’ orthodoxy has, first of all, been much more forceful in areas beyond Sino-Hungarian relations. Secondly, there is little evidence beyond such PR coups of Hungary spending real political capital in the Council to advance Chinese causes. On the key actionable EU policy of FDI screening, Hungary’s opposition was weak. The Orbán government may cultivate strategic allegiance with China, but it is under no illusion that its value as an ally is in fact as a functional Single Market and council member.

This reality evidently constrains the political economy effects of Chinese flows. Everything from the texts of Sino-Hungarian bilateral investment treaties (BITs), to workers’ rights, to health and safety in joint business operations, must comply with EU standards or risk losing wider Single Market access. The recent European Commission investigation into the poor procurement process of the Chinese-funded Budapest-Belgrade railway underlines this point well. With the threat of pan-EU punishment, the Chinese contractor quickly froze construction plans and the Hungarian government re-ran its tenders immediately.

Serbia: The Unbearable Lightness of Being One of China’s Junior Partners

Serbia’s more gradual transition from a planned economy eroded its historic regional competitive advantage in manufacturing and positive terms-of-trade position. Currently, Serbia accounts for almost half of trade with China in the West Balkans, and that trade is almost exclusively tilted toward imports. Chinese FDI in Serbia is concentrated in big-ticket and politically sensitive infrastructure and energy projects. In contrast with Hungary’s, there are early signs of this more skewed relationship leading to greater institutional divergence between Serbia and the EU.

By 2000 (after the Yugoslav wars), Serbia was at a strategic phase of transition not dissimilar to Hungary’s ten years prior. Both were exiting a command economy qualified by tolerance of private enterprise and ties to the West. Both were encumbered by critically large current account deficits and debt-to-GDP levels. Both were oriented toward heavy industry. Indeed, in spite of its wars, in 2000 Serbia was outpacing its Western Balkan neighbors in GDP growth. The post-war Serbian government espoused similar priorities to Hungary at the equivalent point, of privatization of inefficient SOEs, labor market reform, and currency and debt sustainability.

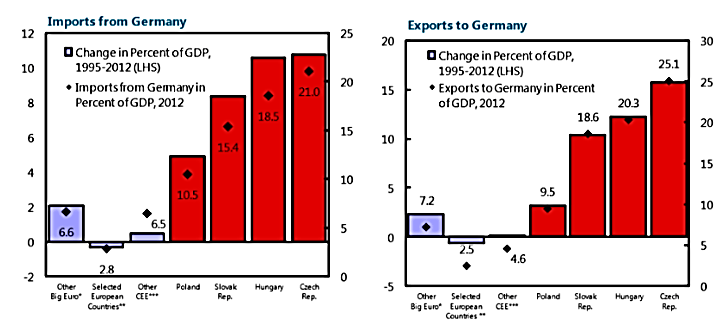

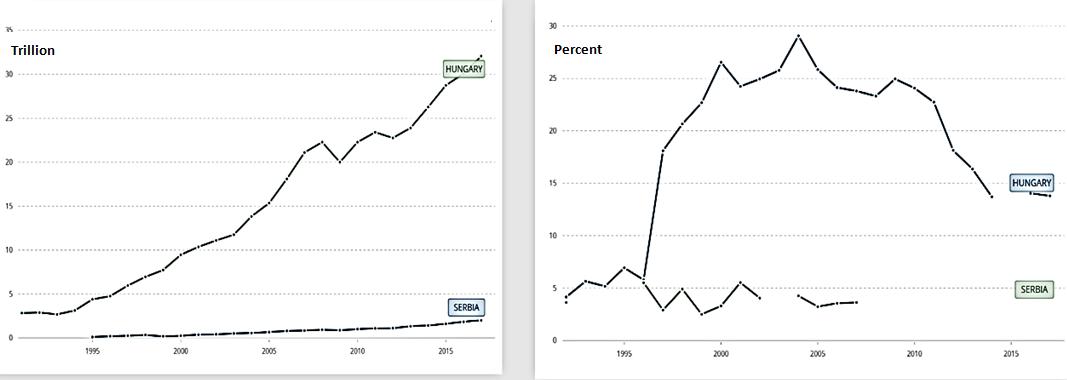

Yet several factors hampered this trajectory. Firstly, Serbian growth was concentrated in non-tradable sectors: retail, communications, and transport. Quite contrary to Hungary’s experience integrating into German supply chains and then climbing up the value chain, Serbian industrial value declined. Serbian exports were consequently a fraction of what Hungary had achieved at a similar point in transition.

Figure 4: Exports as Capacity to Import & Share of High-Tech Manufacturing

Source: World Bank

Secondly, a captured approach to public spending prioritized wealth extraction and clientelist transfers to public sector employees over growth-enhancing investment. Evidence for this appears in corruption scandals, the slow pace and poor results of privatization and the low untick of FDI. Moreover, wage growth throughout the 2000s remained above productivity growth. Productivity, in turn, did not benefit from the rapid transfer of technology and integration into Western Europe (and notably Germany’s) system of supply chains and voluntary industrial norms that accounts, in part, for Hungary’s transformation (See Figure 4).

Serbia’s strides toward EU accession have not fundamentally altered this structural challenge. It was only in 2012 that Belgrade was able to move forward a Stabilization and Association Agreement signed with the EU in 2007 and achieve candidate status to the EU. The European Commission considers Serbia only “moderately prepared,” or less, for accession on most of its criteria and has only closed negotiations in two of its 35 accession chapters. The processes of accession have not led Serbia to meaningfully integrate into European supply chains. This can be seen by the overall worsening of Serbia’s trade balance before and after transition, absolutely and relative to Hungary’s. It can also be seen in Serbia’s inability to expand exports to the key partner in the region’s global value chains, Germany.

It is therefore no surprise that whilst Serbia accounts for almost half of trade with China in the West Balkans, the lions share of that trade’s value is produced (and, therefore, earned) in China. Chinese FDI in Serbia is concentrated in two big-ticket infrastructure and energy projects: the Serbian section of the Budapest-Belgrade railroad project and the construction of the Mihajlo-Pupin Bridge across the Danube in Belgrade. Others have been agreed in principle and are being drawn up in practice: a 45 km highway linking Serbia with its Western Balkan neighbors; a plan to construct a new metro system in Belgrade; and a project to electrify Belgrade’s bus system. A Chinese firm has invested in Serbia’s first windfarm and there are also reports of a Huawei contract to support the Serbian government’s information software and overhaul the national telecommunications system.

In contrast to Hungary’s experience, the absence of Single Market leverage appears decisive for the political economy effect of this relationship. Unlike Sino-Hungarian ones, Sino-Serbian BITs, contracts, and projects follow terms more favorable to Chinese standards and juridical procedure. For instance, the Chinese state-owned EXIM bank was awarded a contract via private and exclusive tender to renovate the Serbian thermal power plant Koslolac in 2014. Not having an EU grade environmental impact assessment, the renovation violates the EU Energy Impact Assessment (EIA) directive. This directive has been integrated into Serbian law as part of the country’s accession commitments. Yet because Serbia is not an EU member, the breach stills falls outside of the European Court of Justice’s punitive power. Such examples are common in the energy and commodities sectors.

China-led divergence is not yet significant enough to shape Serbia’s strategic position as an EU applicant. Yet there are considerable leverage implications, for instance, of Chinese investment in Serbian steel. The single acquisition of the Smederevo steelmaker, in 2016, accounts for a rise in China’s share of Serbian FDI of from 3.5 percent to 9.2 percent. The steel mine is the largest in Serbia, is highly inefficient, and is politically sensitive due to a powerful union presence. The large foreign currency loan attached to it weighs on Serbian foreign exchange commitments. Given current debt levels, it would be an early candidate for restructuring in the event of a downturn and a large depreciation of the Serbian dinar.

Conclusions

These early experiences suggest that CEE countries’ relationships to the BRI depend meaningfully on integration into global supply chains and into the EU. Serbia’s relative slowness on these two fronts shaped its current role as a low value-added transit economy and a political and economic rule-taker. Hungary’s regional economic and political integration made it a high value-added intermediary to Chinese flows and counterbalances the weight of China’s strategic influence and political economy.

In closing this analysis, it is worth noting that the BRI is in its infancy. The trade corridors it creates over time will amplify the effects described here, and this leads to two broader conclusions. First, the BRI presents a long-run challenge to EU neighborhood and accession policy. Rising Chinese imports, credit, and infrastructure investment in Serbia will diminish (though are unlikely to replace) the incentive structure of accession policy. The EU is no longer the only shop in town.

Second and relatedly, this analysis provides context to the Franco-German-Polish initiative to overhaul EU competition policy. The proposed reform envisages rewriting state-aid and anti-trust policy to permit the emergence of larger European multinationals in telecommunications, railways, energy, and so on. The BRI dynamics discussed in this memo clearly motivate the initiative: Chinese SOEs outcompeting their European counterparts for tenders; their greater size and consequent higher appetite for risk-taking (making them at times the sole supplier of large infrastructure project that will not generate profits for decades and that EU institutions like the European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development shun); and consequent risk of regional strategic and regulatory divergence.

Sebastian de Quant is a graduate of the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at Johns Hopkins University and an Associate at Political Alpha.

[PDF]

Homepage image credit.