Readers of the Western press might think that the only paramilitary or mercenary forces participating in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are Yevgeny Prigozhin’s Wagner group and Ramzan Kadyrov’s Kadyrovtsy. Yet this is far from a complete picture. This memo adds nuance to our understanding by highlighting another group, the Russian Cossacks. Data shows that the Cossacks are a growing component of Russian forces in Ukraine, with over 15,000 fighters in the warzone and hundreds of thousands more to draw on. The diversity of Russia’s forces is important to keep in mind for anyone interested in a speedy resolution to the war as well as informed speculation about what will follow. The existence of multiple groups of “specialists in violence” suggests that one plausible scenario for post-war Russia could be civil war.

Western Myopia

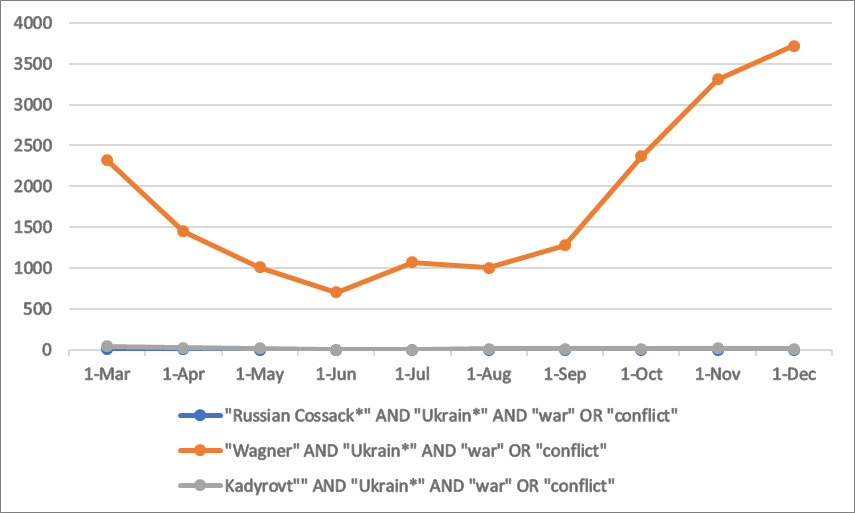

With the exception of a couple of analysts (see my articles here and here and Paul Goble’s here), Western observers are silent about the role of the Russian Cossacks in the war. Using the content of newspaper articles as a proxy for the attention of Western analysts, Figure 1 shows the result of searches on LexisNexis for terms related to the Wagner, the Russian Cossacks, and the Kadyrovtsy. The Kadyrovtsy are included as another well-known and sometimes-publicized group who were discussed at the beginning of the war but seemed to have faded. There are other tiny groups of fighters ranging from the Rusich movement, the Russian Imperial Legion, neo-Nazis, and foreigners like Syrians, but these groups do not merit attention due to their minuscule numbers. As can be seen in the figure, Wagner has received, by far, the bulk of Western attention, and the Kadyrovtsy and Cossacks hardly register.

Figure 1: Western Attention on Component Parts of Russia’s Forces

The search had to specify “Russian Cossack” because the Cossack archetype is also an important element of Ukrainian national identity, and many Ukrainian warriors define themselves as “Cossacks.” This constraint notwithstanding, there were only 28 references to Russian Cossacks in the ten months under study, versus 152 for the Kadyrovtsy and a whopping 18,234 for the Wagner group. Thus, it is fair to conclude there is certain myopia on the part of Western analysts regarding the composition of Russian paramilitary forces in Ukraine.

The Number of Russian Cossacks

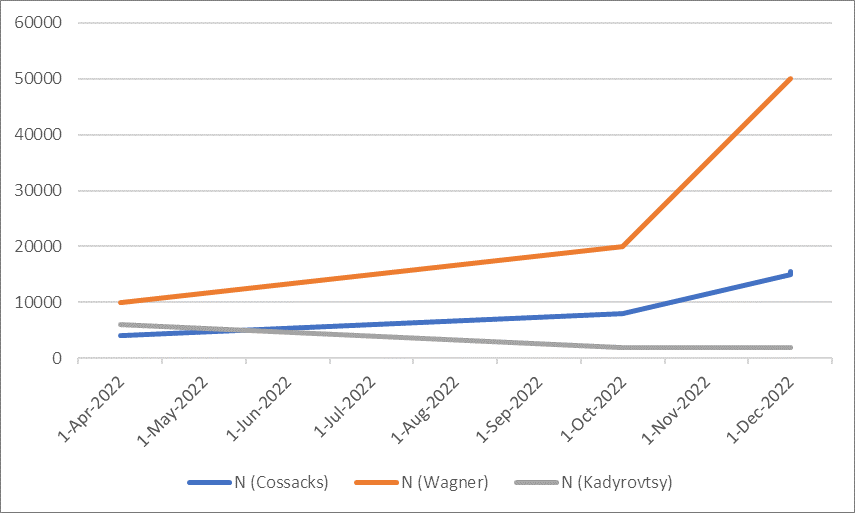

To make the case that the Cossacks are worthy of our attention, I compared their numbers with estimates of the quantity of Wagner troops and Kadyrovtsy in Ukraine. As no one really knows exactly how many troops are in Ukraine from each group, I used estimates from experts for Wagner and the Kadyrovtsy instead. The Cossack numbers, however, are self-reported in articles on their central website, and various news reports describe their military activities. One such report details how Cossack units “such as Don, Terek, Iset, and Listan, as well as military personnel of the so-called Union of Cossack soldiers of Russia and abroad” control the Kinburn Peninsula on the shore of the Black Sea near the mouth of the Dnieper river. Dozens of Cossack “volunteers” in this area have been awarded medals by the Russian president, and major shelling continues from this location toward Ochakov and Mykolaiv. Figure 2 below shows the differing number of troops from each entity since the start of April 2022.

Figure 2: Estimates of Russian Paramilitary Groups in Ukraine

As can be seen in the figure above, the number of Wagner troops (at 50,000) in Ukraine is the highest and underwent a steep spike following Prigozhin’s prison recruiting campaign. The Kadyrovtsy remain at very low levels, being noted more for their brutality than their effectiveness.

At the time of writing, there are purportedly 15,500 Cossacks in the warzone, and the number has been increasing steadily over time. There are reasons to believe this increase will be more sustainable than that of Wagner. First, there is a larger reserve on which to draw: some 750,000 Cossacks are listed on the state register (officially registered Cossacks receive uniforms, ranks, stipends, and privileges). Second, many Cossacks are motivated by both a (distorted) version of patriotism as much as money. In contrast, Wagner’s troops are mostly motivated by financial incentives or getting out of prison early. Third, there are already signs that prisoners are refusing to go and fight for Wagner as they realize safety in prison is preferable to risking life on the battlefield.

Priming the Hosts

News from Russia suggests that the authorities are preparing the Cossacks for a bigger role in the war. In Siberia, far from the conflict, the movement is opening “training centers for the preparation of volunteer Cossack brigades” from the Siberian, Irkutsk, and Yenisei Cossack groups. While early in the war, Cossack volunteers on the battlefield were mainly drawn from the Krasnodar and Rostov regions—close to Ukraine—recruitment has been occurring from further afield. The All-Russsian Cossack Society website reports that volunteers have been coming from Sakhalin and Primorsky in the far east. A fighter from the Sakhalin-Kuril Cossack Society said:

“We were the first across the country to come to the military enlistment office, because the daylight hours on Sakhalin begin earlier than anyone else. The Cossacks themselves expressed their desire, and wrote applications to get here. To participate in a special operation, I personally do not need high motives. I am here for my brothers, for my family.”

This speaks to the point that Cossack troops are likely to be much more highly motivated than their Wagner peers. Such sentiments might not be replicated verbatim across the 12 Cossack hosts (voiska) in Russia, but they are surely shared by a significant number of Cossack volunteers. Indeed, much has been made of the religious component of the war and how the Kremlin has enlisted the aid of the Russian Orthodox Church, but for the Russian Cossacks, the war does indeed have an additional poignancy.

The lands of eastern Ukraine, where the war is being fought, are sometimes seen as the birthplace of the Cossack archetype, with the region of Zaporizhzhia as the site of the Cossack fortress (sich) in the 16th century taking an analogous position as a civilizational line of divide like Jerusalem or Kashmir. Noting the close identification of Russian Cossacks with Zaporizhzhia is not endorsing their views, but it does support the notion that they will be among Russia’s most motivated troops. Of course, the Cossack archetype is also important to ordinary Ukrainians, and the majority of Ukrainians to whom the author has spoken about the Russian Cossacks say that they are not genuine Cossacks, a legacy of Russian propaganda from a bygone era.

The Birth of a “Sub-Ethnos”?

Russia’s Cossacks are split into “free” Cossacks, who claim the identity by virtue of descent, and “registered” Cossacks, who perform duties on behalf of the Russian state. All available evidence indicates that the Russian Cossacks fighting in Ukraine are “registered.” In the strange Russian taxonomy of ethnicity invented by the Eurasianist intellectual Lev Gumilev in the 1980s, the Cossacks are a “sub-ethnos” of the greater Russian ethnos, meaning basically a related people but with their own specific biological factors, customs, and traditions. (They were initially allowed to register as “Cossacks” on the Russian census in the 1990s, but that option was removed in the early 2000s.) While the validity of Gumilev’s taxonomy is debatable, to say the least, it could not even by its own logic apply to those who become Cossacks by virtue of services rendered. Yet such is the conflation around the term that the registered Cossacks also are covered by it, and the reasons lie in the origins of the state-organized movement.

Repressed under the Communists, the early 1990s saw a period of grassroots Cossack revival. In 1995, the government launched the Cossack register designed to bring them into alignment with state structures, but it was not until 2005 that the types of service Cossacks were able to perform for the state expanded greatly. At that time, the Cossacks were organized into ten separate hosts covering Russia’s territory—the Don, Kuban, Terek, Orenburg, Volga, Siberian, Yenisei, Zabaykalsky, Irkutsk, and Far Eastern. The year 2007 saw the creation of a separate host, the Central Cossack host (including Moscow). The Black Sea Cossack host was added in 2015 and included Crimea.

Further reform in 2012 again expanded the list of Cossack duties and opened new connections to the Russian Orthodox Church. The movement was centralized in 2018 with the creation of the All-Russian Cossack Society headed by Nikolai Doluda—the former chief (ataman) of the Kuban Cossacks. As a sign of Doluda’s importance to the regime, there is evidence that he knew in advance about the timing of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Today, there are plans to introduce a 13th host in northwest Russia (St. Petersburg and Kaliningrad) as well as some discussion of creating Cossack structures in newly-annexed Ukrainian land after the war, similar to what happened in Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts.

The last point is crucial because it suggests, as with the point made above about Russian Cossacks being probably more motivated, a focus on the status of Zaporizhzhia in Cossack mythology. The region of Zaporizhzhia is home to the river island of Khortytsa, the ancestral home of the Cossacks and the location of the sich before it was razed by Empress Catherine in 1775. Most of the Cossacks were resettled in the Krasnodar region, with a few relocating to the mouth of the Danube. The conceit that Cossacks are an integral part of Russian history is demonstrated by President Vladimir Putin’s deranged essay, “On the historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” from July 12, 2021, where they are mentioned no fewer than five times.

Yet, as has been mentioned above, Ukrainians guard the idea of the Cossacks and claim it as integral to their nation. Such contestation plausibly lends the current conflict the air of an ethnic conflict—or, more precisely, a conflict for ethnicity and which goes some way to explaining the casual nature with which Putin has been targeting Ukrainian civilians. This also suggests that Cossacks represent a sizeable pro-war constituency in Russia.

Russia’s Cossacks: Quo Vadis?

The Russian Cossacks are, therefore, an important component of Russia’s armed forces but one that has hitherto been overlooked by most analysts of Russia’s war in Ukraine. Their existence suggests two further lines of inquiry, which should be at the forefront of analysts’ minds as the war continues.

First, Russia’s military and paramilitary troops are not monolithic, and as outlined in this memo, there are many different groups and subgroups within it. Further research might ask what other groups exist, why there are so many fractures, and what this suggests about the limits of Putin’s power. One possibility is that various armed segments serve as a kind of krisha (roof, or protection racket) for powerful individuals in Russia in the event Putin leaves or dies. Prigozhin has Wagner, Kadyrov, his eponymous thugs, and Zolotov, the national guard. The political figure closest to the Cossacks is “Orthodox Oligarch” Konstantin Malofeev, who sponsors them and promotes them through his Tsargrad television channel. The implication is that a power struggle could determine succession and could lead to a second civil war. Russia has unclear political succession rules, ethnic grievances, and an increasingly armed populace, among other simmering issues. In a country with nuclear weapons, the eventuality of domestic clashes must be taken seriously (see my article here).

Another implication that has not really been seriously touched on yet by any scholar or analyst of whom I am aware is the latent potential of Russia’s “free” Cossack movement. The “free” Cossacks were included on the Captive Nations List of 1959 in the United States, and some emigres dreamt of an independent Cossackia (see examples here and here). More recently, ancestral Cossacks tried to form their own republic in the 1990s and, for a long time, were in confrontation with the government. Sources known to the author suggest that in the event of a collapse of central Russian authority, as has been outlined in the previous paragraph, the “free” Cossacks might again start their activism for a homeland state. Another possibility is that affinity for Ukraine runs more deeply among such Cossack groups than that for Russia, and so they become a kind of internal fifth column. Until Western analysts start paying more serious attention to the Cossacks, however, any development from among their ranks will continue to surprise us.

Richard Arnold is Associate Professor of Political Science at Muskingum University.