Elvira Nabiullina was appointed head of the Russian Central Bank in 2013 with a mandate to clean up Russia’s deeply fraudulent banking sector. (source)

► Banking has increasingly become nationalized in Russia, raising concerns that all private banks may be forced from the market within 10 or 15 years. In the short run, this consolidation enables the government to continue funding its numerous and expensive commitments and thereby maintain social and political stability. David Szakonyi discusses the political consequences of this creeping nationalization of the Russian banking sector and warns that they may be less auspicious in the longer term.

Through all the gloom of Russia’s stagnating economy, one bright spot has been the prudent macroeconomic policy coming from the Central Bank. Under the leadership of Elvira Nabiullina, Central Bank policymakers have helped navigate the country through the treacherous waters of international sanctions, volatile oil prices, and downward pressure on the ruble. Perhaps, more importantly, they have overseen a widespread cleanup of the country’s fraught banking sector. Hundreds of Russian suspect private banks have had their licenses revoked, while regulators have provided massive bailouts to at-risk financial institutions such as Otkrytie and Binbank.

Nonetheless, a dark cloud hangs over this positive news. As the clean-up winds down, state-owned banks now control over two-thirds of the total assets in the sector. What is more, many of these leading state-owned banks are rapidly expanding their presence in other dynamic industries such as IT and retail, indirectly enlarging the Russian government’s footprint within the economy. This piece explores the many political consequences of the consolidation. Concentrating banking resources in the hands of the state provides a sturdy safeguard against political and financial destabilization. These banks can strategically step up their lending activity in the run-up to competitive elections as well as facilitate tighter control over political financing. The creeping nationalization of the banking sector can have large downstream effects on the ability of both companies and political parties to compete in Russia.

Sanitizing Banks

|

“Millions of dollars, often times stolen directly from depositors, had been stashed abroad under the guise of fictitious consulting contracts and loans that would never be paid back.”

|

The Russian banking sector had long been due for a shake-up. For years, the banking sector has occupied a profitable but gray niche in Russia’s emerging market economy, offering the new capitalist class opportunities to evade taxes, send their capital abroad, and procure cash for privatization schemes. But rampant mismanagement and sometimes outright corruption has resulted in a flurry of non-performing loans and speculative, risky transactions. Policymakers have long worried that problems within the banking system pose a serious threat to Russia’s economic stability.

When former Minister of Economic Development Nabiullina took over the Russian Central Bank in 2013, her mandate was to immediately clean up the sector. As regulators probed deeper into individual bank balance sheets, the depth of the fraud sparked fears of systemic failure. Hundreds of banks had massive holes in their capital structures. What made matters worse: millions of dollars, often times stolen directly from depositors, had been stashed abroad under the guise of fictitious consulting contracts and loans that would never be paid back. Capitalizing on a variety of bank document links, international journalistic investigations have regularly exposed elaborate money laundromat schemes leading back to unscrupulous Russian banking practices. For officials serious about reducing capital flight and even repatriating some of the money that had fled, going after the compromised intermediary banks was a logical place to start.

Nabiullina has won praise from many, both in Russia and abroad, for several bold new approaches to cleaning up the sector. Smaller banks lost their licenses and were allowed to fail, while temporary administrators were brought in to fix some larger entities deemed too systemically significant. Later on, massive bailouts from the government were used to recapitalize targeted banks and return them to profitability, and hopefully back into the hands of private investors.

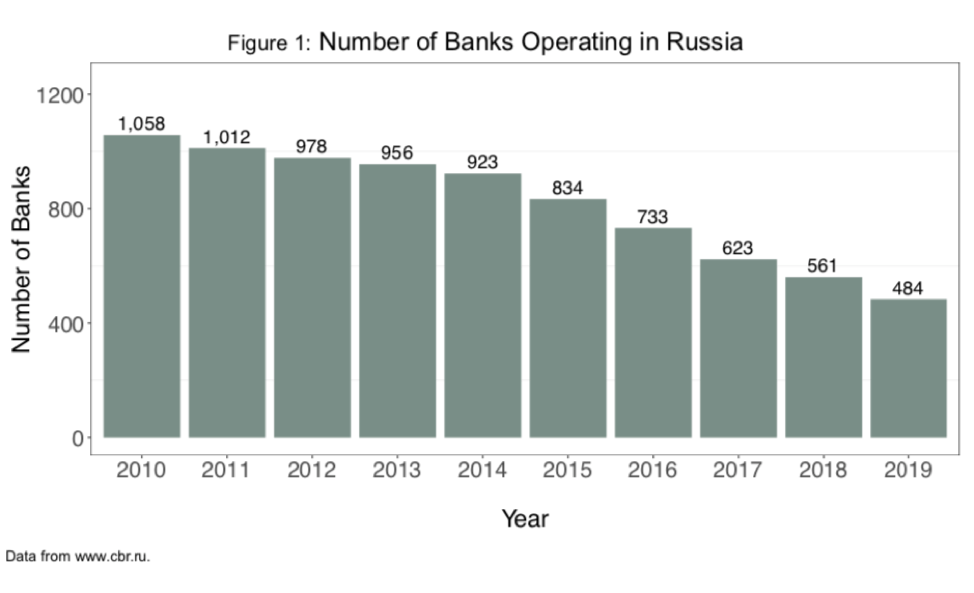

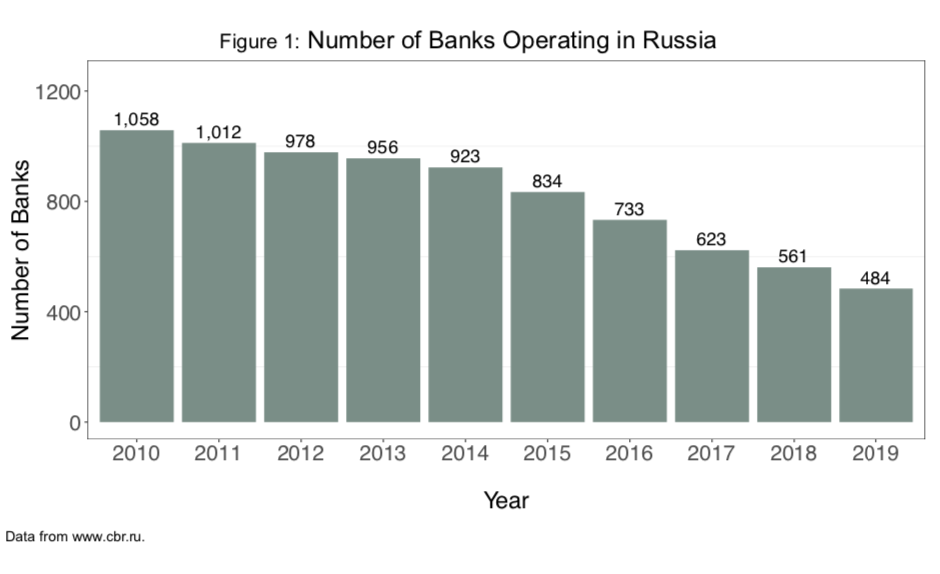

Figure 1 plots the contraction in the banking sector accelerated by the banking cleanup. From 2010-2019, the number of banks operating in Russia has fallen by 54%, from 1,058 to 484, with the sharpest decline occurring since 2013. Compare those numbers to the previous decade when only 20% of the banks operating in 2001 had lost their licenses by 2010.

The crackdown has produced some surprising casualties. In April 2019, Central Bank officials revoked the license of a small regional bank in Ivanovo that was primarily owned by former U.S. Congressman Charles Taylor (R-NC); the bank was suspected of having violated money laundering regulations and artificially inflating its capital. In 2017, oligarch Gleb Fetisov, a former member of Russia’s Federation Council, was temporarily jailed on accusations of having stolen $11 million in deposits after exiting the failed My Bank. It seemed few were untouchable.

These moves have not come without costs. Indeed, analysts are still trying to calculate the bill imposed on the Russian government. One estimate from last year put the total price tag since 2013 at over 6 trillion rubles, a little more than twice what the government plans to spend on the military in 2019. Why so high? Most of the money went to reimburse customers through Russia’s federal deposit insurance program. And in many cases, the liquidated banks had been completely looted by investors, leaving the state with worthless assets.

State-Owned Banks Alone at the Top

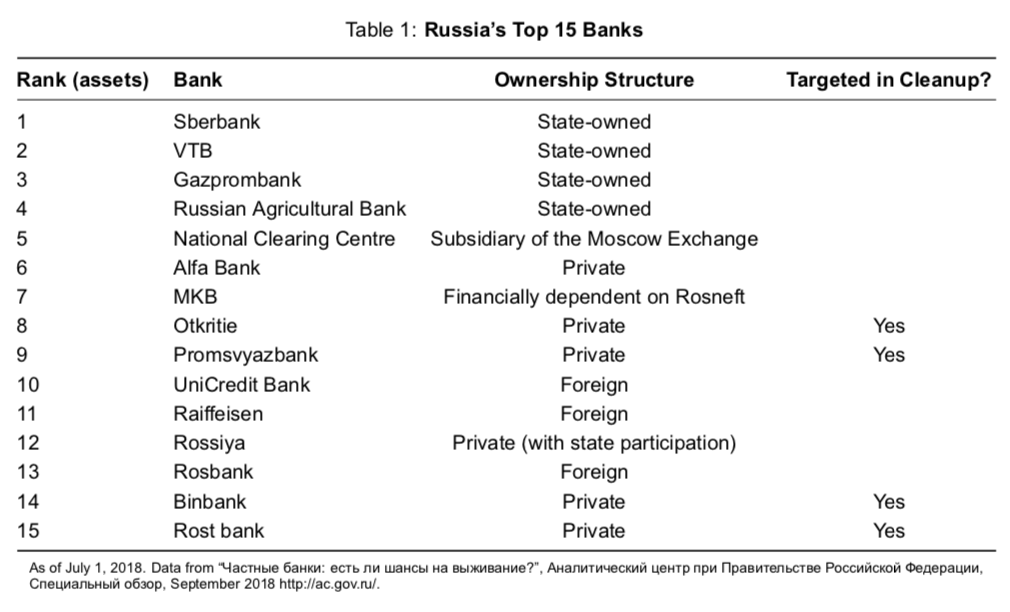

Besides the financial commitments, recent concerns about the scope and nature of the cleanup have centered on the distribution of ownership within the sector. Table 1 lists the top 15 banks still operating in the country as of July 2018. Four of the top six private banks in the country have been nationalized; two of these, Otkrytie and Promsvyazbank, had been listed among the ten largest banks operating in the country. This is in addition to the hundreds of small private banks that have lost their licenses since the crackdown began.

The overall banking market has thus sharply tilted in favor of banks currently owned by the Russian government. The top four state-owned banks listed in Table 1 alone now control over 55% of the total assets in the sector. In comparison, the country’s largest private bank, Alfa, controls just 4% of assets. This itself may not last long. In December 2018, Alfa co-founder Mikhail Fridman announced that a deal in principle had been made to sell the bank to either state-owned VTB or Gazprombank. So far, no details have been released, but the deal could spell the final demise of large private ownership in the sector.

|

“The largest private bank, Alfa co-founder Mikhail Fridman announced that a deal in principle had been made to sell the bank to either state-owned VTB or Gazprombank.”

|

A recent report by the think tank Analytical Center for the government of Russia sheds more light on just how much the crackdown has affected the public-private sector divide within the banking system. Given the negative attention surrounding the clean-up, many borrowers, both firms and individuals, now view private banks as less reliable and trustworthy financial actors. To attract customers, private banks have had to raise the interest rates on savings accounts, which creates a drag on profitability. As of September 2018, state banks accounted for over 80% of lending to corporate entities and 70% of lending to individual persons. With international majors such as Morgan Stanley, Deutsche Bank, and Credit Suisse all reducing their presence in Russia, state-owned banks also enjoy fewer obstacles to dominate the investment banking market.

Beyond capitalizing on their collateral and regulatory advantages, state banks have joined the mergers and acquisitions fervor at work in many Russian sectors. By the end of 2018, VTB had announced plans to acquire majority stakes in three smaller rivals—Vozrozhdeniye, Sarovbisnesbank, and Zapsibkombank—helping it enlarge its regional footprint. Hopefully, history will not repeat itself: VTB’s disastrous hostile takeover of Bank of Moscow in 2011 wound up costing the Russian government $13 billion in bailouts.

The Politics of State Control Over Banking

Russian authorities have been careful to avoid talk of nationalization within the banking system, referring instead to the Central Bank’s actions as temporary steps taken to stabilize the situation. Back in the 2000s, the government takeover of Russia’s leading industrial giants in natural resources, defense, and heavy industry spooked investors, foreign and domestic alike. Officials instead point to the many praiseworthy achievements with regards to combatting money laundering and enforcing transparency in a banking sector rife with corruption. But until private investors can be found to take over the bailed-out banks, the government will be left with plum majority stakes and near complete control over the system.

Creeping nationalization brings with it a host of political consequences. First, independent financial capital often generates political diversity. Economic elites around the world bankroll alternative political actors that challenge the status quo offered by the regime. After all, political parties require substantial funding to buy advertising time, pay activist salaries, rent offices, and broadcast their platforms to voters. In research on political coalitions in Africa, Leonardo Arriola has drawn attention to the importance of private ownership within the banking sector for helping pay these costs and for promoting political competition. When African governments liberalized their banking system, businesspeople with access to private financial capital began funding political challengers.

|

“The government could push through loan forgiveness programs to ease economic pain and secure much-needed votes in competitive elections.”

|

We are in the midst of a reverse trend in Russia. As banking becomes more nationalized, the Kremlin gains the unlimited capacity to control the financing of political parties and any projects deemed political. Banking oligarchs from the 1990s like Mikhail Fridman appear content to move onto international pursuits. Gleb Fetisov caught the unwanted eye of law enforcement authorities coincidentally after he declared plans to start a political party. New players such as Oleg Tinkoff have conspicuously stayed out of politics. And there appears to be little daylight between the views of the Kremlin and the powerful heads of the state-owned banks, such as Andrei Kostin of VTB and Yuri Kovalchuk of Rossiya Bank. The pool of politically active capital is weighted heavily toward one side.

Beyond preempting the rise of the well-resourced opponents, state control in the banking also helps the government weather downturns in popularity. Some of this activity is explicitly geared to win elections. Economists have linked Putin’s ascent to power in the March 2000 elections to increases in regional corporate lending by Sberbank. Funneling extra cash to firms before elections helped incentivize employers to mobilize their workers to turn out to the polls. With a presidential succession potentially in the works in 2024, these tactics could accelerate. Millions of Russian workers already face pressure from their bosses to vote for regime-sponsored candidates. If employers cannot turn to private lenders for financing, they may be unable to resist the political strings attached to loans from state-owned banks.

State control over the banking sector also can facilitate lending to certain sectors of the economy where the workforce might be peeling back its support from the regime. For example, state-owned banks could step up loans to agricultural firms working in hard-hit rural regions and single-industry towns which still have not recovered from the 2008 economic crisis. This type of pre-electoral manipulation is significantly harder for journalists and political challengers to detect, but can keep voters employed and positively inclined towards the government.

New Economic Juggernauts

With Russian state-owned banks now redoubling their efforts to attract individual consumers as clients, new opportunities for political interference also could crop up. To stimulate the construction sector and help solve housing issues, the government already offers subsidized mortgages run through the commercial banking sector. Concerns are growing that the median Russian household is sinking underwater in personal debt. The government could push through loan forgiveness programs to ease economic pain and secure much-needed votes in competitive elections. We saw similar tactics being used to great effect during the last national elections in Georgia. A coordinated program for strategic lending to state-owned enterprises and retail loan forgiveness would complement the elaborate spending plans within national projects that Kremlin officials have trotted out to shore up popular support and kickstart anemic economic growth.

Less well-appreciated are the repercussions that the rise of state-owned banks will have far beyond the financial services sector and electioneering. Over the past decade, state-owned banks in Russia have invested billions to diversify into different sectors of the Russian economy. We are already seeing the emergence of vast, diversified holding companies, backed by a seemingly endless capital supply and regulator-approved “hunting licenses” that extend the Kremlin’s hand into sectors once thought off-limits for the government.

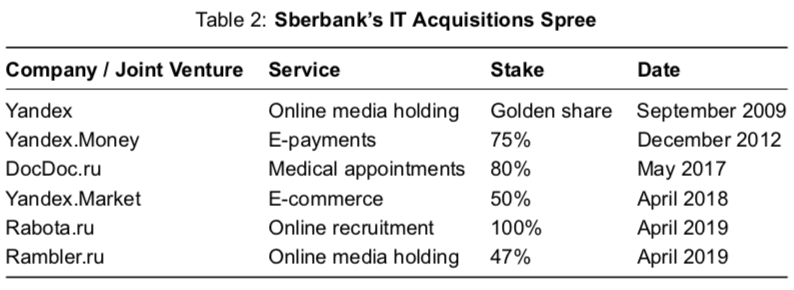

Let’s begin with the IT industry. The country’s largest bank by assets, Sberbank, has made no secret of its desire to become an internet company. Since 2009, it has held a golden share in Yandex, meaning it can block large equity sales of Russia’s largest technology company and search engine. As Yandex has expanded into different market segments, Sberbank has stepped up to help foot the bill. A $1 billion joint venture to develop the online marketplace “Beru” has been billed by Sberbank CEO German Gref as the “Russian version of Amazon.”

Table 2 documents the bank’s growing interest in the IT sector, including the latest acquisition of a large stake in Rambler.ru, which boasts many of Russia’s popular media entities such as LiveJournal and Lenta.ru. Sberbank is even rebranding as “Sber” (the way Sberbank is referred to in informal speech) to mark this pivot towards IT. Investors have not always looked kindly on this expansion. Just rumors of Sberbank potentially purchasing a 30% stake in Yandex sent down shares of the latter company by as much as 10% in October 2018.

Not to be outdone, another state-owned bank, Gazprombank, also has worked to get in on the IT market boom. In late 2018, Gazprom announced plans to develop a new blockchain tech partnership with Megafon and Rostec, Russia’s massive state-owned defense conglomerate. Another joint venture with Sberbank will focus on voice and facial biometric systems and professional data processing.

|

“In completing the Rambler sale, Sberbank would exert direct or indirect control over two of Russia’s most prominent, homegrown IT companies. With that ownership comes access to limitless personal data on personal citizens.”

|

It’s still too early to evaluate all the potential consequences of the country’s largest banks fully owned by the Russian government that are developing a strong interest in building IT empires. In completing the Rambler sale, Sberbank would exert direct or indirect control over two of Russia’s most prominent, homegrown IT companies. With that ownership comes access to limitless personal data on personal citizens. The building blocks of the sovereign Runet may have less to do with kill switches and content blocking, and more with the incorporation of big tech into state hands.

VTB has charted its own diversification course, with an emphasis on picking off several assets owned by influential oligarchs. Following the arrest of Ziyavudin Magomedov in late 2018 on racketeering and embezzlement charges, VTB took over stakes in several of his most lucrative companies, including a grain trader and a freight transport company, to settle the oligarch’s outstanding debts to the bank. Shortly thereafter, VTB announced plans to buy a grain terminal located in Novorossiysk, giving it control over the transport logistics of one of Russia’s fastest growing exports. VTB also appears to be one of the beneficiaries of Oleg Derispaska’s divestment from Rusal in 2018 under pressure from the U.S. government: the state-owned bank accepted Rusal shares in exchange for outstanding debt.

All of this followed on the heels of VTB’s groundbreaking purchase in early 2018 of 29% of shares in Magnit, Russia’s second largest retailer, from its founder Sergei Galitsky. Here again, we see a state-owned bank pushing the envelope with significant investments into several of Russia’s most profitable sectors: metals, agriculture, and retail. Nationalization of key assets is being accomplished indirectly but mirrors the patterns first observed in the 2000s.

A Chance to Reverse Course?

Amidst the backdrop of growing concentration, the Federal Antimonopoly Service has largely stayed on the sidelines and has not yet been directed to use its antitrust mandate at reforming the banking sector. The litany of reform “road maps” trotted out have done little to level the playing field between state and private banks. For instance, it remains to be seen how regulators plan to evaluate tiers of banks based on their size, rather than ownership. Government officials appear to accept that the benefits from keeping tight ownership control over the lending giants appear to outweigh the substantial risks.

|

“Government officials appear to accept that the benefits from keeping tight ownership control over the lending giants appear to outweigh the substantial risks.”

|

Last year at a conference of private bankers, alarms were raised that if the Central Bank refused to intervene to curb the power of the state-owned majors, all private banks could be forced from the market within 10-15 years. Sberbank already eats up the lion’s share of profits within the sector. Analysts urged regulators to place strict restrictions on the market share that state-owned banks could hold in different segments. Calls have even made been to break up the big banks themselves, though it’s anyone’s guess what kind of capital holes might be discovered in that scenario.

In the short-term, allowing this consolidation to unfold will continue to stabilize the financial sector, as well as the broader political system, for the many reasons outlined above. However, history is a guide for what happens if proper regulation and oversight of large state-owned banks lag their expansion. VTB alone has received five bailouts from the Russian government since 2008, helping it survive throughout crises, inflicted both externally and internally. Moving forward, there may not be enough money to go around to fund all of the Kremlin’s expensive commitments.

David Szakonyi is Assistant Professor of Political Science at George Washington University,. He is also a Research Fellow at the International Center for the Study of Institutions and Development at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, and an Academy Scholar at the Harvard Academy for International and Area Studies.