(PONARS Policy Memo)The oil price shock that began in mid-2014 has continued to reverberate in Azerbaijan, sending the economy into deep recession and negative real GDP growth rate (-2.4 percent in 2016). Declining volumes of oil production, which peaked at 1 million barrels a day (b/d) in 2010, and impending depletion of petroleum reserves over the next 15-20 years, alerted the government of the need to boost the non-oil sectors of the economy. In a series of national development plans and strategic road maps, the authorities pledged their commitment to diversify.[1] However, there are two paramount factors that stand in the way of Baku’s plans: domestic “petrodollar recycling” and U.S. strategic disengagement from the region. The former is when externally generated oil surpluses are “sunk” into local real estate and infrastructural development projects, which then discourages movement of capital into non-oil sectors. The latter means a loss of strategic importance and attractiveness to foreign investors. Low commodity prices and President Donald Trump’s alleged isolationist outlook do not bode well for Azerbaijan’s intent to reorient and diversify its economy.

Recycling of Petrodollars

The last (and final) major oil boom cycle (2005-2014) in Azerbaijan’s history generated a spectacular $125 billion in state oil revenue for the state oil fund (SOFAZ). Intended as a savings and stabilization fund, this sovereign wealth fund has so far been able to set aside some $35 billion, or 28% of these total assets as strategic reserves, with the rest being injected into the national economy.

The way Azerbaijan has been consuming and investing its oil earnings follows a “recycling of petrodollars” model. This activity refers to the inward and outward flows of dollar-denominated oil proceeds between oil-exporting countries and the rest of the world. When oil prices are high, large cash surpluses can be invested in foreign assets or spent on imports of goods and services; when commodity prices tumble, oil exporters move the money back home to smooth out foreign exchange losses and cover domestic capital needs. The only way in which Azerbaijan’s “recycling” differs from that of the Gulf States is that Azerbaijan seems to have recycled most of its oil earnings at home rather than into global financial markets.

Throughout the oil boom years, Azerbaijan pursued less than a cautionary fiscal policy, embarking on an extravagant spending spree in apparent disregard of its own fiscal rules. In the domestic market, the biggest winners were the construction and real estate infrastructure development sectors; the cost of urban renovation alone between 2012-2015 is estimated at $18 billion. Up to 35 percent of the annual state budget during the oil boom years was allocated to infrastructure and construction projects.

A circle of local construction firms, subcontractors, banks, and offshore shell companies linked to powerful figures from within the elite network serves as the main channel of petrodollar recycling. The extent to which an oil exporting country has the capacity to spend all the oil receipts at once represents that country’s absorptive capacities. Investment was hard pressed to go toward human capital, which in Azerbaijan is marked by generally low levels of vocational-technical training and higher education, and rather high levels of technological backwardness. Spending on a few, but capital-heavy, infrastructure projects had the advantage over human-capital intensive projects in that it avoided the dispersal of capital outside the core elite, allowed for the feeding (and appeasement) of competing patronage networks, and enabled a more controlled process of petrodollar recycling. The unintended consequences, however, are rising youth unemployment and a “youth bulge” that might eventually burst because the closed political system lacks the safety valves necessary to release demographic pressures.

Azerbaijan’s SOFAZ was another channel to recycle petrodollars through both budget transfers and the acquisition of foreign capital assets. The foreign assets of SOFAZ include fixed income, bonds, equities, gold, and real estate. Its conservative asset policy generated a modest 1.2 percent return on investment (the Fund’s revenues from asset management totaled only $425.4 million in 2015). The downside of this channel is that it does not contribute to job creation domestically and therefore amplifies the youth bulge.

Agriculture Wiped Out

Azerbaijan’s capital investment approach unleashed the forces of Dutch Disease syndrome. As large sums of oil-generated foreign exchange were converted into the national currency, the real exchange rate appreciated, wiping out nascent private businesses outside the energy sector. As a result, today, oil and natural gas still account for about 90 percent of total exports and 30 percent of GDP (this is discounting for oil-boosted construction and services).

Agriculture and manufacturing have over the past decade been decimated by pressures from the appreciating Manat (Azerbaijan’s currency) and a lack of funding. It would have helped had a portion of funding gone to agriculture, which would have vastly dispersed wealth outside of the elite-centered money-recycling network. Agricultural production, a traditional sector believed to hold the most promising comparative advantage and potential to generate non-oil export revenues, declined and instead the (non-export oriented) non-tradeable sectors such as services (hotels, restaurants, banks) and construction grew, in keeping with Dutch Disease syndrome. According to official statistics, the share of agriculture in the GDP fell from 16 percent in 2000 to 9 percent in 2005 and to 6.2 percent in 2015 while the share of non-tradeable construction almost doubled from 6.5 percent in 2000 to 12 percent in 2015. Light industry (textiles, processing of foodstuffs) suffered as well due to outdated equipment and insufficient investment.

A major policy shift is usually successful when there is a strong constituency pushing for reform. Due to Soviet legacies, Azerbaijan’s private sector outside the oil industry has been weak and toothless against the wealthy elites who have high stakes in the oil sector. A smaller number of private sector entrepreneurs are often linked to the political elites, are dependent on state support, and do not possess the independent power base necessary to advocate for reform. For the ruling elites, large sunk costs associated with domestic petrodollar recycling make economic diversification economically unattractive and politically cumbersome even though higher diversity in exports would make the economy less vulnerable to oil price and volume volatility in the long run.

Real Estate Mirage

As in many Gulf countries, oil rents were used by Azeri elites and oligarchs to boost their real estate projects and their business interests in the construction and services industries. The plan of modernization articulated and pursued by the Baku government was remarkably similar to the one embraced by the Gulf states, which included a vision in which the state would facilitate turning Baku into a modern metropolis and a major transportation hub with high-rise buildings, modern shopping malls, luxury boutiques and techno-parks, all of which would presumably provide the state with sufficient fiscal revenue when it runs out of oil in 15 to 20 years.

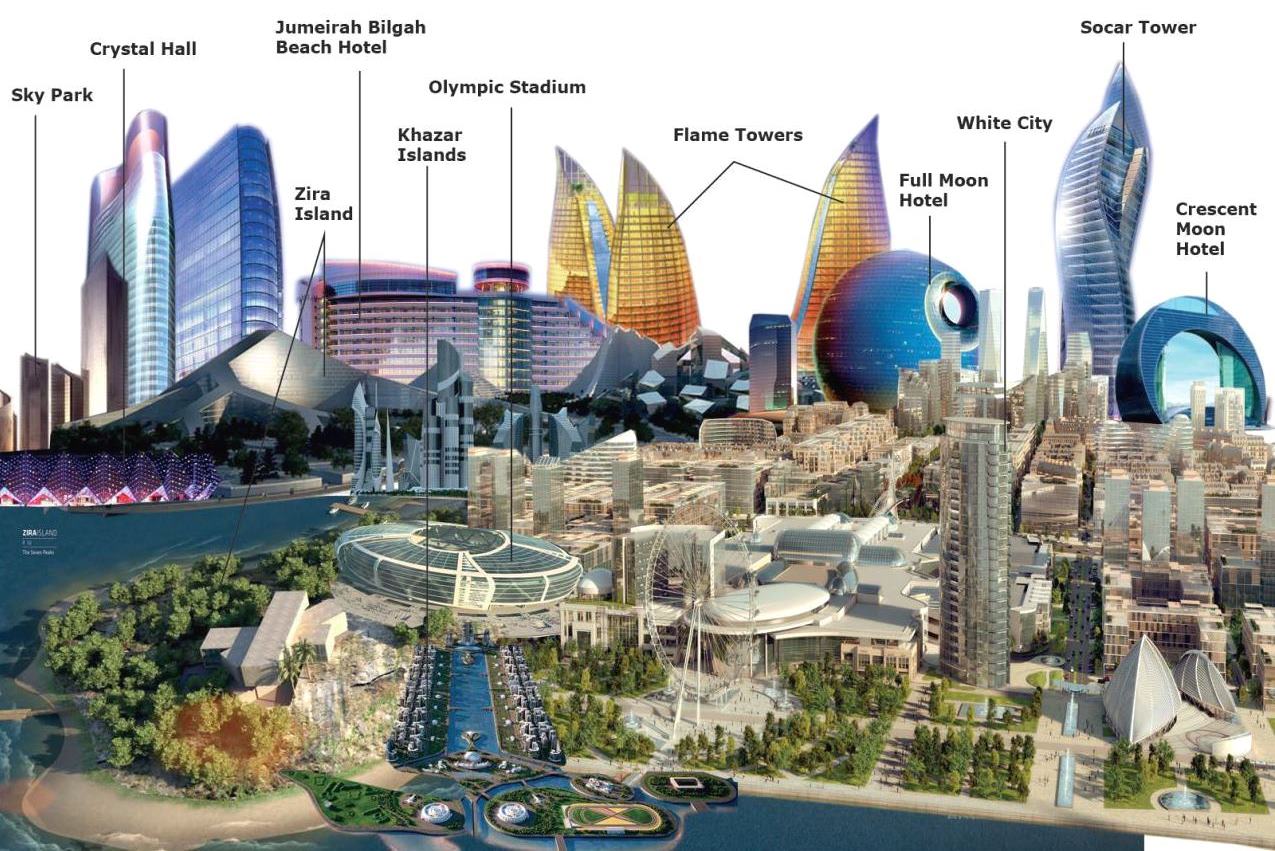

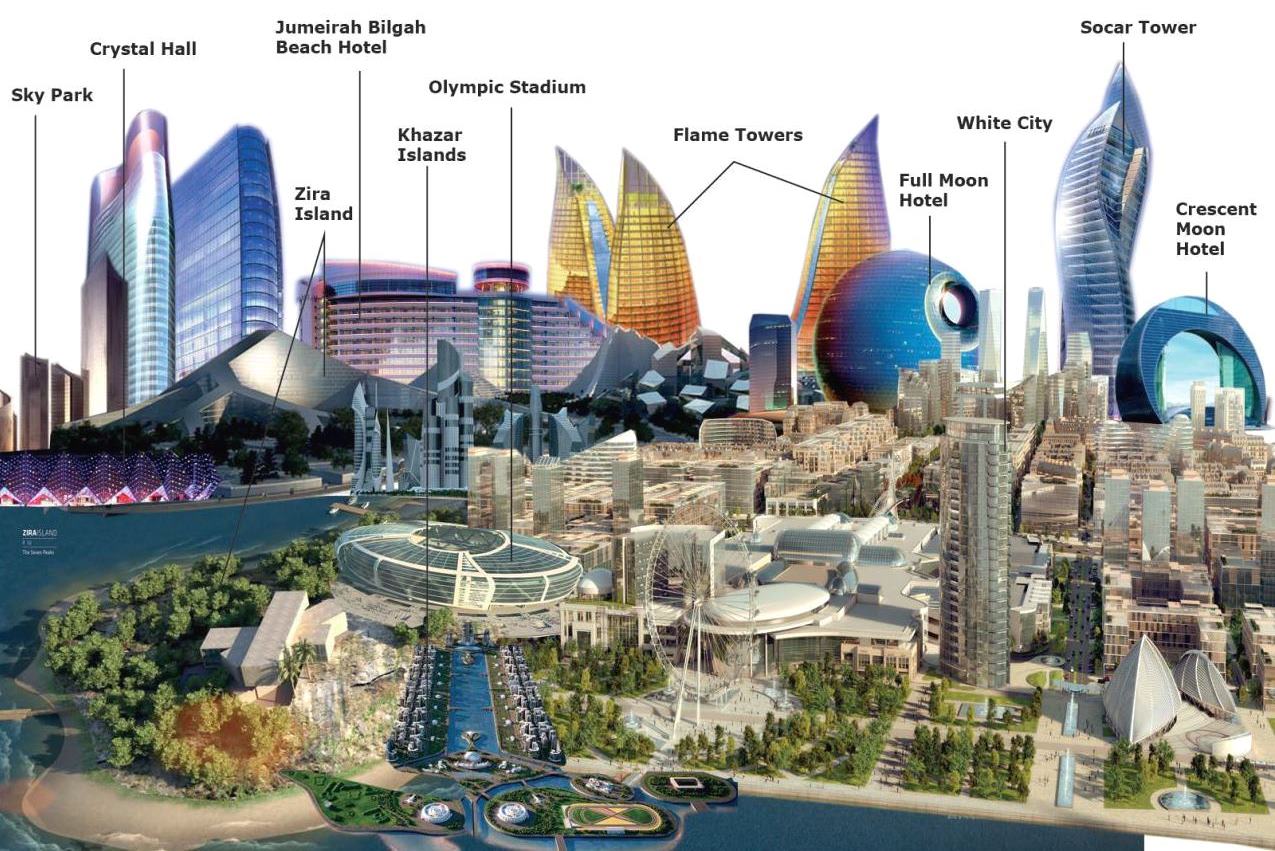

The unusually long period of high oil prices between 2004 to mid-2014 provided a conducive environment to realize this vision. First, the idea was to upgrade infrastructure (roads, highways, gas stations, airports). Then, new residential complexes (such as White City and Port Baku Residence), skyscrapers (such as Flame Towers), five-star hotels, and expo centers were to be built (see Figure 1). Later, the emphasis would be placed more on capital-intensive projects such as techno-parks, real-estate development, and logistic/transportation facilities, such as a new seaport and a new rail link to connect Azerbaijan to Turkey. (Of note, as a sign of grand plans, in 2013 an Azerbaijan-owned satellite built for $230 million by a US-based company was launched into orbit).

Figure 1. Baku’s Urban Skyline Circa 2020

Source: Francisco Colom, Emma Gabalda, and Vicente Plaza

White elephant projects are favorite petrodollar recycling schemes. They have no life without preferential state support and would go out of business under normal competitive conditions. A good example is Khazar Islands, a $100-billion real estate project that would have consisted of “an archipelago of 55 artificial islands in the Caspian Sea with thousands of apartments, at least eight hotels, a Formula One racetrack, a yacht club, an airport, and the tallest building on earth (“Azerbaijan Tower”). Launched toward the end of the oil boom cycle by the Avesta Concern company that has an obscure ownership structure, it was completely abandoned once oil surpluses faded through 2015-16.

International Linkages

Foreign capital tends to flow into places that enjoy Western strategic interests. Over the past five to six years, the U.S. government has been losing its interest in Central Asia and the Caucasus while Russia has been trying to reassert its dominant role. As Fiona Hill and her colleagues noted:

“2010 marked the end of the long phase of focused U.S. attention, including in Caspian energy development. As political and commercial attention shifted from the export of Azeri oil to the export of gas to Turkish and European markets, the United States ceded the stage in regional energy diplomacy.”

This disengagement will likely continue under the Trump administration given his isolationist rhetoric regarding U.S. foreign policy and his personal sympathy for Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Low oil prices will dampen foreign investment in the Caspian region. Structural changes in global energy markets, with a notable increase in supply from new producers in the Americas (including the United States), may also discourage investment in overseas markets. As global financial flows bypass the region following the loss of strategic importance, there is a high risk that Azerbaijan will be further marginalized. Attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) is further exacerbated due to the landlocked position of the Caspian Basin. The region is generally considered a high-risk environment due to its distance to end-users in the West. Azerbaijan’s non-oil white elephants, such as automobile plants in Nakhchivan and Ganja or the techno-park in Pirallahi, are unlikely to be attractive either.

When domestic sources of cash are in short supply, oil-producing states can turn to international investors or lenders. So far, alongside burning through more than two-thirds of its currency reserves in 2015, Baku turned to international loans to finance its gas transit plans, growing its balance of payments deficit and, thus, has been piling up debt. In recent months, the government borrowed $1.73 billion from Asian lenders (ADB and AIIB) and $400 million from the World Bank to finance the expansion of the Shah Deniz II gas field and for the construction of the TANAP Gas Pipeline (aka Southern Gas Corridor) which is estimated to cost $45 billion.

Azerbaijan fears losing the United States as a crucial source of foreign investment that the country desperately needs to complete its planned regional energy transit and logistics hub megaprojects embodying the government’s vision of a post-oil future. When a region’s strategic importance decreases, oil states are often pushed to reform to attract additional foreign investment. U.S. engagement, whether conditional or not on reform, is needed to attract FDI. This may explain why no effort was spared and large sums of oil money have been used to boost the country’s image abroad through an aggressive political marketing campaign and lobbying activities in the United States.

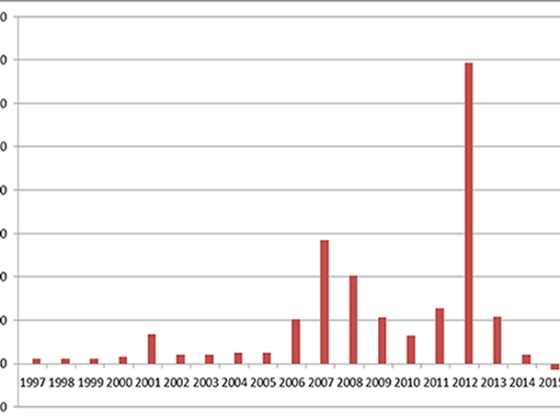

From 2012 to 2016, Azerbaijan hosted several major entertainment and sporting events, including the Eurovision Song Contest, European Olympic Games, and Formula 1 Grand Prix. In the United States, the Azeri government has hired lobbying firms (such as the Podesta Group) to promote its interests in the U.S. Congress. Most recently, amid falling oil prices, the Azerbaijan state oil company, SOCAR, funded and gave expensive gifts to ten Congress members and their staff to participate in a trip to Baku.

In December 2016, following the victory of Donald Trump, the Azerbaijan embassy in Washington threw a Hanukkah party with the participation of the influential American Jewish group, Conference of Presidents, and chose the Trump Hotel in Washington, DC, to host the event. The timing was picked carefully to occur the day after Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu paid a visit to Baku.

Conclusion

More than a decade into the “second oil era,” diversification remains a major challenge for Azerbaijan. The odds are, however, stacked against diversification. Much of its domestically recycled petrodollars are mostly sunk costs that cannot be converted back into investable capital to promote alternative sectors should the government proceed with major reforms. Compensatory capital can only come from external sources, but on this front, too, recent developments are not in Azerbaijan’s favor.

The United States has been effectively disengaging from the broader region, leaving Russia to reassert its regional prominence. Loss of Western strategic interest will drive away the region’s attractiveness to foreign capital. With Trump’s victory, the U.S. interest and role in the region is likely to diminish even further. Azerbaijan will thus be hard-pressed to diversify, and its diversification drive is unlikely to receive the support it needs from state-dependent private sector elites.

Farid Guliyev is a Research Associate at the Eurasia Extractive Industries Knowledge Hub, a regional focal point of the Natural Resource Governance Institute at Khazar University, Azerbaijan. From September 2016 to February 2017, he was a Fulbright Scholar at the Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies (IERES) at the George Washington University.

[PDF]

[1] See: Long-Term Oil Strategy (2004), Vision 2020 (2012), and a series of strategic roadmaps announced in December 2016 covering the financial sector, agricultural development, ICT, logistics, trade, and other sectors.