The Azerbaijani establishment is in a bind. With two neighbors (Turkey and Georgia) now oriented toward the EU and three (Armenia, Russia, and Kazakhstan) opting for the Customs Union (CU), Azerbaijan is trying to balance between the two for as long as possible. Tilting either way has its pros and cons; neither offers a win-win situation.

The Pros and Cons of the Customs Union

At first glance, the CU would appear the preferable choice for Azerbaijan. Baku’s membership in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) has not brought anything negative to Azerbaijan. On the contrary, it eased Azerbaijani-Russian relations after a tense period in the early 1990s and, with its visa-free regime, addressed the problem of high unemployment in Azerbaijan by allowing for massive labor migration to Russia. Joining the CU now would increase the ability of Azerbaijani products to penetrate neighboring markets. In addition, the import of cheap Russian food products would decrease prices and benefit a large share of the population.

However, the overall cost of joining the CU is far greater than these benefits. Azerbaijan’s largest trading partner is not Russia but the EU. In 2011-2012, between 48-52 percent of Azerbaijani exports went to the EU, while between 26-32 percent of Azerbaijani imports came from there. Azerbaijan exported mainly energy resources and imported machinery, vehicles, textiles, and foodstuffs. Joining the CU would not alter the structure of Azerbaijan’s imports, but it would raise the cost of vital products as it would force Azerbaijan to impose CU-level tariffs on various goods.

Moreover, free trade with the EU would be less damaging to Azerbaijan’s agricultural sector. The cost of agricultural products in the EU is comparatively high, and at least not less expensive than Azerbaijani products. With transportation costs, it will not be profitable for EU states to export agricultural products to Azerbaijan. This is not the case with Russian, Belarusian or Kazakhstani agricultural products. Imports from CU members could destroy Azerbaijan’s agriculture sector, which employs about 40 percent of the country’s workforce.

Azerbaijani political and economic elites oppose CU membership. In December 2012, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev said that Azerbaijan did not see that joining the CU (or the Common Economic Space) made economic sense (although he stressed that once Azerbaijan sees the benefits of any association, it would join without hesitation). At the same time, joining the CU would undermine the position of many local oligarchs, who are very close to the government and who reap considerable benefits from the Azerbaijani economy’s monopolistic nature. While oligarchs in Armenia and, to some extent, Kazakhstan and Ukraine have business interests in Russia, Azerbaijani-based oligarchs have their businesses concentrated in Azerbaijan and Turkey. For these oligarchs, joining the CU raises the specter of the economic “Armenianization” of Azerbaijan—the swift buying out of the economy by Russian oligarchs and companies. Ethnic Azerbaijani oligarchs who live in Russia, like Lukoil president Vagit Alikperov and billionaire Telman Ismayilov, do not have sizeable business interests in Azerbaijan. They have little ability to influence the Azerbaijani political establishment to move toward the CU.

The Azerbaijani public is also not so keen on the CU. The October 2013 Biryulevo ethnic riots in Russia electrified Azerbaijani society and became a source of anti-Kremlin feelings. In early October, an Azerbaijani migrant in Moscow, Orkhan Zeynalov, fatally stabbed a Russian citizen, Yegor Shcherbakov. A few days later, a crowd of Russian nationalists provoked riots and led to the destruction of the Biryulevo market, where many migrants work. Zeynalov was arrested, but his humiliating detention and interrogation, as well as the anti-migrant hysteria that surrounded the case, sparked a wave of negative emotion in Azerbaijan. Although many Azerbaijanis understood that the harsh circumstances of his detention were meant to extinguish the massive protests in Moscow, they greatly damaged Russia’s reputation in Azerbaijan. Many Azerbaijanis (experts included) considered the case against Zeynalov to be a fabrication designed to put pressure on Baku to join the CU. Some politicians in Moscow have used the Zeynalov case as justification to call for introducing a visa regime with Azerbaijan (as was the case with Georgia back in 2006-2007).

Controlling travel and deporting Azerbaijanis from Russia would lead to even more tension. According to Russia’s last census, there are over 600,000 Azerbaijani citizens in Russia. Unofficial estimates put the number at up to 2 million. These migrants account for a large share of financial transfers from Russia to Azerbaijan. According to Ruslan Grinberg, director of the Institute of Economics of the Russian Academy of Science, private remittances sent from Russia to Azerbaijan amounted to $1.8-2.4 billion a year in 2009-2010. Although this is not a large share of Azerbaijan’s GDP, it is a major factor in poverty reduction, especially in rural areas. Surprisingly, however, the Azerbaijani government has not shown much concern about this. Azerbaijani ambassador to Russia Polad Bulbulogly has even noted that Azerbaijan is ready to institute a visa regime with Russia, if the latter insists.

Although media attention toward the Zeynalov case has waned, it is hard to underestimate its impact on Azerbaijani perceptions of Russia. Seeing how Russian law-enforcement agencies treated one Azerbaijani citizen was enough for many to conclude that the Russian-led CU is not for them. The ghost of Russian xenophobia and nationalism will continue to cast a shadow on ordinary Azerbaijanis’ perception of Russia. The episode also further spurred greater official interest in forging a closer relationship with the EU, where Azerbaijani citizens have not been treated with humiliation and deprivation.

Eventually, Kremlin officials began producing statements trying to pacify the tense mood. Mikhail Shvydkoi, special presidential envoy for international cultural cooperation, told journalists in Baku that relations with Azerbaijan are one of the priorities of Russian foreign policy, and that this policy does not depend on isolated, especially criminal, incidents.

European Union: Pros and Cons

Cooperation with the European Union is one of Azerbaijan’s foreign policy priorities. For the EU, Azerbaijan’s strategic location and European dependency on gas and oil make it a valuable partner. For its part, Azerbaijan looks to the EU as a market for its resources and with the hope that the EU can become a force to counterbalance Russia in resolving the Karabakh conflict. In the past, EU assistance has been critical to Azerbaijan; since 1991, the EU has provided 333 million euros to Azerbaijan in technical, humanitarian, emergency, and food assistance. There are many benefits to deeper cooperation with the EU via an Association Agreement. EU investments in the non-oil sector may also be critical for Azerbaijan’s efforts to diversify its economy.

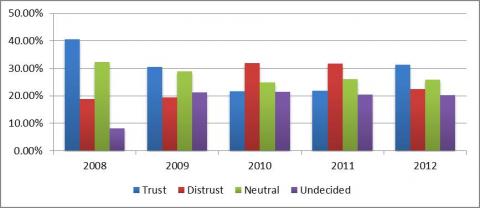

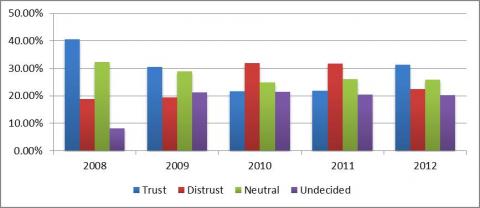

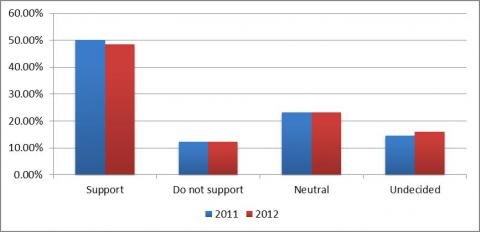

A more active EU policy in Azerbaijan could win the hearts of many. The Azerbaijani public has traditionally regarded the EU with a comparatively high level of trust. In 2008, around 40 percent of respondents trusted the EU while under 20 percent did not. The Russian-Georgian warand the financial crisis had a negative impact on the Azerbaijani level of trust in the EU. In 2010-2011, the percentage of respondents who distrusted the EU grew to a record 30-33 percent while the percentage of those who trusted the EU dropped to almost 20 percent. Only in 2012 did the level of trust in the EU again surpass the level of distrust, reaching 32 percent versus 22 percent. Still, many Azerbaijanis are either neutral or undecided. At the same time, almost 50 percent of Azerbaijanis surveyed in 2011-2013 have consistently supported the country’s membership in the EU. Only 11 percent are against such membership, while significant numbers are still either neutral or undecided.

Table 1. Trust toward the EU

Table 2. Support toward becoming an EU member.

There is, however, one major problem with EU association that makes the Azerbaijani elite uncomfortable: the EU’s constant criticism of human rights violations, corruption, and the absence of reforms in Azerbaijan. The Azerbaijani establishment understands that continued movement toward the EU will force Azerbaijani elites to pursue significant reforms in public administration, respect human rights, and open up local markets. This all leads to the further democratization of the country, something that could undermine the current government over time. Thus, the Azerbaijani elite is ambivalent in its approach toward EU-led projects. It wants to be part of these projects but without significantly changing the country’s system of governance. Nonetheless, the government is continuing to negotiate a large-scale partnership agreement with the EU that envisions various aspects of cooperation including trade and political partnership.

Conclusion

Azerbaijan is left with the option only to procrastinate. Azerbaijani elites understand that their country’s future lies with greater integration into Europe. Sooner or later, Baku will opt for deeper cooperation. For now, however, the costs are too great. As for the CU, Baku does not wish to openly ignore Moscow’s interests; it hopes to bide its time until the CU discredits itself. In the worst case, Baku may opt to sign some kind of political declaration promising to keep its markets open to Russian goods and services.

The situation may change after the twin TANAP and TAP gas pipeline projects across Turkey and southeast Europe are implemented. Azerbaijan will then become a vital partner for the EU and a major component of its energy security. This may lead Baku to believe this will lead to greater economic and security guarantees for the country and its elites, dampening concerns about the consequences of closer integration with the EU. Until that time, Azerbaijan walks a thin line between the EU and the CU, as the EU focuses its integration efforts elsewhere and Russia attentively watches its every step.

[View PDF]