In the runup to the 2021 Russian parliamentary (Duma) election, the Russian Central Election Committee announced a series of changes to the voting process, including the introduction of electronic voting in several regions and an extended, three-day voting period. Critics condemned these changes, arguing that they increase opportunities for falsification away from the public eye. However, these administrative changes did not generate the same level of public condemnation as more overt forms of electoral manipulation, such as carousel voting or ballot box stuffing. According to a September 2021 poll by the Levada Analytical Center, the vast majority of Russians (68 percent) were supportive of the extended election period. While opinions were split on the introduction of electronic voting—46 percent were supportive of it compared to 41 who were not—less than half of those who expressed concerns with the online system cited the potential for falsification as the reason for their concern. Overall, Russians viewed the 2021 elections as being slightly more fair than the parliamentary elections five year prior; 14 percent of Russians stated that the 2021 elections were fair, compared to 10 percent for 2016.

Perceptions of the fairness of the voting process impact support for governments and their leaders and may ultimately lead to collective action that can destabilize regimes. However, it is not the mere presence of electoral manipulation that impacts attitudes toward the regime. Instead, the type and visibility of fraud matter. When manipulation violates “the rules of the game” and is viewed as worse than usual, it influences perceptions of the ruling power. Less overtly fraudulent practices—such as the expanded voting period and introduction of online voting—are not as likely to be perceived as leading to falsification and, therefore, are less likely to incite public ire while still providing opportunities for authorities to unduly influence results.

The 2011 Parliamentary Election

All fraud is not created equal. To understand how the visibility of electoral manipulation has influenced political attitudes in Russia, we must go back to the 2011 parliamentary elections. Widespread allegations of manipulation and fraud marred that December 4 election. Local and international media reported serious irregularities in the voting booth before and after the election. Numerous cases of ballot stuffing and carousel voting were caught on camera and posted on YouTube. Election observers were barred from witnessing the sealing of ballot boxes, activists were harassed, and local websites that attempted to expose the fraud were subject to cyberattacks. These, along with other forms of manipulation, led the OSCE to conclude that the election was subject to “undue influence of state authorities” and that the state “did not provide the necessary conditions for fair electoral competition.”

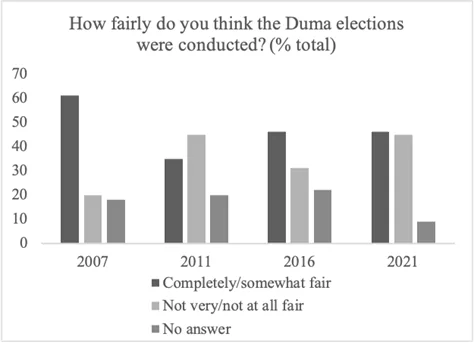

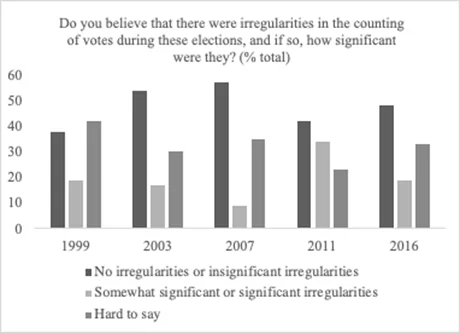

Importantly, the election was perceived as being more unfair than the previous parliamentary elections. Forty-five percent of Russians viewed the 2011 parliament elections as being not fair or very unfair, compared to 20 percent for the 2007 parliament elections and 31 percent for the 2016 parliament elections, according to public opinion polls (see Figure 1). Similarly, 34 percent of Russians thought there were significant irregularities in counting votes in the 2011 parliament elections, compared to 9 percent in 2007 and 19 percent in 2016 (see Figure 2). The 2011 parliament election was also considered to be more dishonest than the subsequent 2012 Presidential election: According to Levada Center estimates, approximately 60 percent of respondents thought that the presidential election was fair, while only 27 percent believed it to be partially or completely dishonest.

Figure 1: Fairness of Parliament Elections

Figure 2: Irregularities in Parliament Elections

While electoral manipulation allowed United Russia to maintain a narrow majority in the parliament, it gave rise to one of the largest protest movements in Russia’s independent history. Ultimately, the regime was able to maintain its hold on power, and Vladimir Putin was reelected for a third term as president in 2012. But the public reaction to allegations of electoral manipulation took authorities by surprise and compelled them to take steps to convince the public of the integrity of the electoral process. Following the 2011 parliament elections, authorities introduced transparent ballot boxes and web cameras in polling stations, placing some constraints on the opportunity for overt electoral manipulation.

Does Electoral Manipulation Impact Trust in the Regime?

But did this perceived egregious manipulation influence attitudes toward the regime? In an ongoing study, I find that electoral manipulation in the 2011 parliament election had a noticeable and significant impact on trust in Putin for select groups.

Leveraging a nationally-represented survey that took place before, during, and after the 2011 parliament election and 2012 presidential election in Russia, I was able to examine how allegations of electoral fraud in the parliament election shifted public confidence in Putin. Directly following the parliament elections (and before the subsequent protests), trust in Putin decreased by ten percentage points compared to pre-election levels—a change attributed to the allegations of visible and blatant fraud. By comparison, there is no evidence of shifts in public attitudes following elections with “average” levels of fraud, such as the 2012 presidential election. Rather, trust in Vladimir Putin decreases when the public perceives electoral manipulation to be worse than usual.

However, not all Russians are equally swayed by allegations of electoral manipulation. Electoral fraud appears to influence trust among people with weak to no political affiliation, such as those who express weak to indifferent support of the ruling party, United Russia. On the other hand, individuals with strongly-held political affiliations do not appear to be swayed by this new information. Regime supporters are less likely to update their beliefs when presented with new, negative information about the government. Regime opponents are more likely to already hold beliefs that manipulation occurs during elections. Rather, those in the middle—who do not have strongly-defined views of the government—are more likely to change their views when presented with information about allegedly high levels of electoral fraud.

Business as Usual?

In non-democracies, authorities frequently rely on electoral manipulation to secure victory and achieve their desired results, particularly when they do not expect to win elections otherwise. But reliance on manipulation can further erode support for authorities, which may, in turn, require the use of even more manipulation to remain in power. However, fraud is only likely to depress views of the regime if the public views the manipulation as being worse than usual. Ballot stuffing, carousel voting, and harassment of election monitors—a few common manipulation tactics—are highly visible to the public and are, therefore, more likely to harm the attitudes of the regime. But all forms of manipulation are not equally visible to the public or even viewed as having the potential for falsification in the first place. Instead of relying on these tactics, authoritarian regimes can use administrative tools—such as increasing barriers to entry, barring oppositional candidates over technicalities, shifting voting periods, or moving to online elections—to subtly manipulate elections, thus limiting the potential costs of fraud.

The most recent parliamentary election in Russia in 2021 exemplifies this shift to less visible forms of manipulation with the introduction of extending voting periods and online voting. According to the head of the Central Election Commission (CEC), Ella Pamfilova, these changes were adopted in order to decrease the risk of COVID-19 infection by reducing overcrowding at polling stations. In reality, these changes benefitted regime candidates, increasing opportunities for ballot stuffing and decreasing the transparency of an already opaque voting process. In Moscow, several opposition candidates who were in the lead lost the election after delayed online votes came out heavily in favor of the ruling party candidates—a result, opposition leaders argue, that owes to the rigging of online votes. According to the CEC, these changes are here to stay.

Conclusion

Experts have argued that the 2021 parliamentary elections were among the most falsified in Russia’s history. Yet the elections were viewed by the Russian public as being as fair as prior ones, in part because the majority of Russians do not see these more obscure tactics as increasing the potential for falsification. In short, the type and visibilityof fraud matters.

The shift to less public and overt forms of manipulation presents new challenges for opposition candidates and leaders hoping to mobilize the public. The changes to electoral procedures ahead of the 2021 parliamentary election were widely seen as a trial run for the upcoming 2024 presidential election—one which appears successful. Despite the allegations, calls to protest following the alleged falsification of online voting results in Moscow were met with limited fervor. Since then, these changes have been enshrined into law, furthering opportunities for the Kremlin to manipulate election results away from the public eye.

To combat these electoral innovations, opposition leaders will first need to raise awareness about how these tactics can create opportunities for falsification by authorities. Tampering with electronic votes through an opaque online system is simply less conspicuous than video footage of poll workers stuffing ballot boxes with votes in favor of Kremlin-backed candidates or harassing independent observers at the polls. The recent crackdowns on the opposition, non-governmental organizations, and the media—repression that has escalated since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022—presents even more challenges to combating Kremlin narratives around these processes. However, there may be some hope: While activists may be unable to reach those with firmly-held political convictions, individuals with weak political affiliations may be more open to messaging that contradicts the dominant, Kremlin-backed narrative.

Hannah Chapman is the Theodore Romanoff Assistant Professor of Russian Studies, and Assistant Professor of International and Area Studies, at the University of Oklahoma.