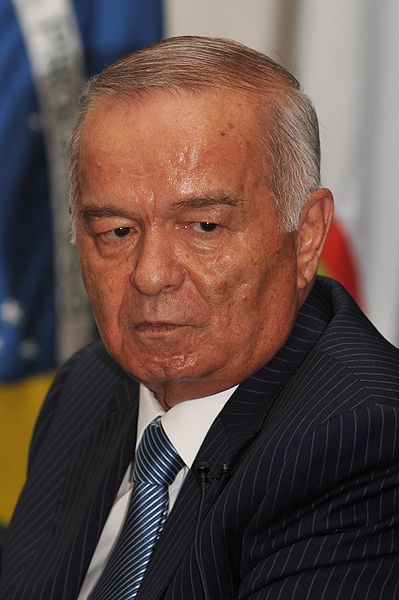

Rumors that Uzbekistan’s 75-year-old president, Islam Karimov, has suffered a heart attack have recently set off speculation of a looming succession struggle in Central Asia’s most populous country. Whether or not these are true–and they have been denied by some close to the president–they highlight how the “stability” that such rulers claim their systems produce can be transitory, potentially leading to civil strife or even civil war. And age is not their friend.

When both formal and informal power is highly concentrated in the hands of a single patron such as Karimov, and when no actual monarchical system is in place to govern succession, he becomes indispensible to the system: Emerging expectations of his departure can open up the possibility of a major battle among insider political networks who both want to claim presidential power for themselves but who also (perhaps even more importantly) fear its winding up in the hands of a rival.

Crucially, it is not just the actual removal of the leader that can cause such problems, but advance expectations that this is likely to occur soon: Better to act now than when it’s already too late. But how to judge? When there are no meaningful term limits or elections, age becomes increasingly important in shaping expectations of a leader’s potential departure. With rising age, reports of possible infirmities become more credible. Such reports also become more ominous, raising the specter of succession and intensifying rivalries within the president’s system, which also makes such rumors more tempting for opposition forces to spread. Round numbers increasingly become reminders of such problems: For the first time I can recall, for example, Russian analysts began discussing Putin’s health as a serious issue as he turned 60 last year–speculation that was (equally tellingly) demonstratively rejected by major TV programming showing a vigorous Putin lifting weights and swimming. Of course, leaders can hope to be as lucky as Zimbabwe’s Mugabe, ruling until at least age 89. But the fates of Mubarak, Qaddafi, Saleh, and Ben Ali in the 2011 “Arab Spring” well illustrate the dangers that age can pose for non-democratic leaders, making their regimes increasingly vulnerable to shocks, though clearly many other factors influence leaders’ political longevity as well.

How well have post-Soviet leaders held onto power after reaching age 70 in office? Shevardnadze (Georgia) and Smirnov (Transnistria) were ousted amidst succession-related ruptures in their own elite. Aliyev (Azerbaijan) barely managed to hand off power to his son before passing away. The only other two in either recognized or unrecognized states to reach this milestone since then, Karimov and Nazarbaev (Kazakhstan), have faced increasingly intense speculation about succession–and especially in the case of Karimov, frequent rumors of ill health. Nazarbaev is helped by high genuine popular support, though even that may be waning now in light of some recent developments.