(PONARS Policy Memo) Vladimir Putin’s new presidential term is shaping up to be the most complicated of his political career. According to the Russian Constitution, he is not allowed to become president again in 2024. Finding a solution for this problem is a major issue for the Kremlin. Either there will be a transition of power or Putin will prolong his rule by making constitutional changes. The uncertainty and vulnerability of this situation is exacerbated by two negative factors: the continuing stagnation of the Russian economy and the country’s partial isolation in the international arena. These two circumstances help explain the outsized significance the Kremlin attached to the 2018 presidential elections, the results of which need to sustain Putin’s legitimacy until the 2024 milestone. In this perspective, it is important to scrutinize the election results and comprehend the particular mechanisms that enabled Putin’s electoral victory. The Kremlin could not rely on, as it had before, “political mobilization” techniques related to its international agenda. Instead, the leadership implemented an “administrative mobilization” formula in workplaces in order to achieve its targeted numbers of both turnout and votes.

Elections Results and the Regime’s Dynamics

Both the results and mechanisms used during this election differ from previous ones in a few significant ways. First, they differ in figures. From 1991 until 2001, the winners’ outcome in presidential elections was in the range of 52–58 percent. These figures reflected the comparative competitiveness of elections, even if they may not have been democratic or fair. This competitiveness echoed political splits in society, competition between elite groups, and comparatively high levels of civic and media freedom. In 2004–2012, the incumbents’ outcomes were in the range of 64–71 percent and reflected the evolution of the political regime to the type that Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way described as competitive authoritarianism. It was characterized by the stable dominance of one political and elite coalition, the reduction of political freedom, and soft repression of the opposition (which had occasional support from elite groups and was able to lean on the minor but relevant sector of independent media). Putin’s 2018 winning figure of 77 percent support, however, seems to be distinctly in the pattern of hegemonic regimes whose election results range from 75 to 100 percent (and that also engage in violence against civic freedoms and hard repressions against the opposition and already-marginal independent media). In other words, with Putin’s 77 percent of the vote, Russia seems to be catching up with various Central Asian elections, which have at times been characterized by election results of around 90 percent.

From “Three Russias” to “One and a Half Russias”

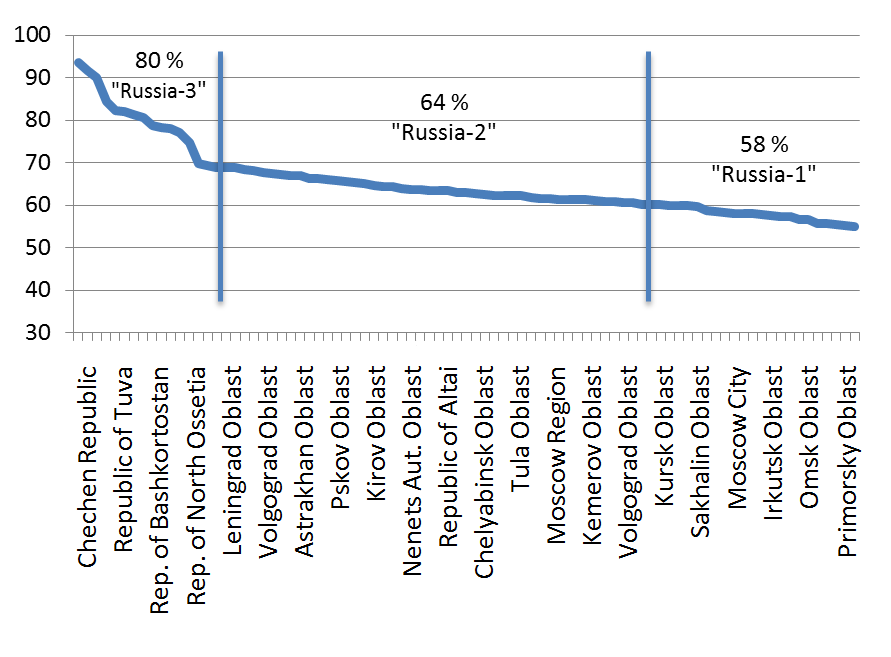

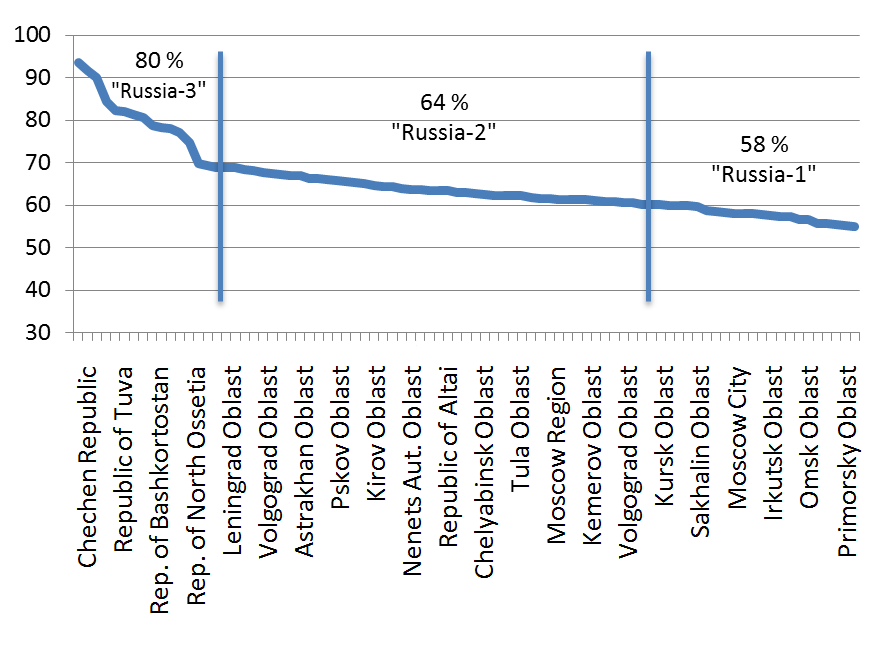

One might discern three types of electoral patterns coexisting in Russia’s electoral profile. Figure 1 presents a selection of the average results of incumbents over 2004–2012 in presidential elections in Russia’s regions arranged on a descending scale. The vertical lines in the figure separate the “Three Russia” types, which coexist electorally, from “Russia-3” on the left to “Russia-1” on the right. On the left, we see that the set of regions has much higher outcomes for the incumbent, about 80 percent on average, with turnout near 80 percent. In the middle we see outcomes of about 64 percent, while on the right, the outcomes are lower, in the interval of 55–60 percent.

Figure 1. Average Votes for the Incumbent in the 2004, 2008, and 2012 Presidential Elections in the Russian Regions

The “Russia–3” regions consist of mostly national republics and some Russian regions that have conservative political and electoral cultures. In these areas, one will not find independent observers at polling stations, independent local media providing coverage, and very few civic activists and organizations. “Russia-3” tends to produce extremely high levels of both turnout and votes for the incumbent. This is likely assisted by huge manipulations and falsifications. Of note, the rare interventions of independent observers at polling stations in “Russia-3” demonstrate that the turnout and outcomes do not differ much from the rest of Russia.[1] In any case, people in this category do not view elections as an institute of political participation.

The regions on the right side of the figure can be defined as “Russia-1.” They are mostly regions that have large urban agglomerations, local organizations of opposition parties, independent observers, and some local independent media. Opposition candidates and parties here tend to receive some votes and the level of falsification is significantly lower than in “Russia-3.” Whereas mass falsifications provoke no scandals and protests in “Russia-3,” they occur in the “Russia-1” districts, as happened in 2011 during the anti-government protests. This category has a more advanced political culture.

“Russia-2 is a sort of mixture of two within the same region. An example is the Nizhegorod region. While in Nizhny Novgorod, the regional capital with four million people, one can find results and turnout very similar to that of Moscow and other “Russia-1” regions, some districts, or regional “backwaters,” voted closer to the model of “Russia-3.” These “three Russias” functioned in a stable and predictable way in both the presidential and parliamentary elections over the 2003–2016 period.

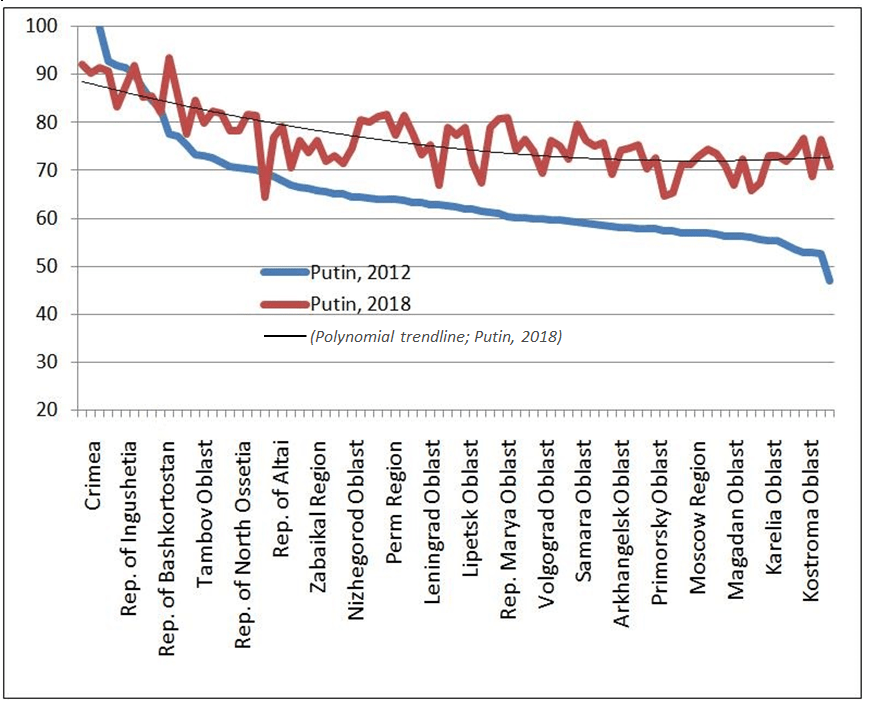

Taking a closer look at the 2018 presidential election results (see Figure 2), the difference between “Russia-1” and “Russia-3” shrank—the chart’s descending tail on the right almost disappears, as shown by the 2018 red line (and its associated black polynomial trendline). Assessing Putin’s victory in absolute figures, one can see that voter turnout was almost the same as it was in 2012 (71.8 million in 2012 and 72.3 million in 2018, excluding Crimea and Sevastopol) while Putin’s vote total exceeded his 2012 mark by 9.6 million (excluding Crimea and Sevastopol). Additionally, more than 6 million new votes came from “Russia-1.” How can this be explained?

Figure 2. Votes for Putin in the 2012 and 2018 Elections in the Russian Regions

Two Possible Explanations: Mobilization or Manipulation

There are two main hypotheses that can explain the 2018 voting scenario, which seems to have morphed “three Russias” into “one and a half Russias.” The first hypothesis, supported by the Kremlin and some independent analysts, claims that Putin’s popularity increased after Russia annexed Crimea, embarked on wars in eastern Ukraine and Syria, and entered into major confrontation with the West. This hypothesis suggests that those who voted for the opposition before had voted for Putin this time. The variation in support for Putin from different social/demographic groups narrowed. Indeed, the election outcomes correspond to Putin’s approval rating: in 2012 it was about 62–65 percent and the election outcome was 65 percent while recently it has been about 80 percent corresponding to Putin’s 77 percent vote win.[2]

The alternative hypothesis supposes that both election outcomes and poll results are biased. Opinion poll results may be biased alongside the worsening of the “opinion climate” (people who are more critical of the authorities and Putin are less inclined to respond to pollsters[3]) while election results may be distorted through two main types of manipulation: direct falsification and “compulsory voting” (or administrative/ workplace mobilization). It is therefore worth paying attention to some strange voting behavior such as the widespread changing of voting station locations in some regions and “early voting” influxes on election day.

When assessing the range of possible manipulations, it should be mentioned, first, that the volume of “abnormal voting,” as estimated via Russian physicist Sergei Shpilkin’s statistical method and interpreted as direct falsifications, did not increase but even decreased in this election.[4] “Abnormal voting” is estimated to have occurred in 8.5 million of the votes in the recent election. Some evidence and statistical clues suggest that while reducing direct falsifications a little, the Kremlin used new techniques of manipulation to increase turnout and votes for the incumbent. This mechanism of “compulsory voting” could at least partly explain not only the higher turnout but also the unusually loyal electoral behavior in urban regions.

A “Five-Touch” System of “Compulsory Voting”

Many analysts predicted lower turnout in this election than in previous cycles. They expected the turnout to be no less than 10 percentage points lower than in 2012. The Kremlin was also heavily focused on the turnout problem. To increase turnout, a colossal “five-touch” information system program was launched. It included the appointment of “responsible persons” in regional and local administrations who coordinated with the owners and directors of large enterprises to make sure they “encouraged” their employees to take part in the elections.

The program was presented like an informational campaign, but regional guidelines that were seen by journalists in Nizhny Novgorod demonstrate that it was more than just information and encouragement. The guidelines mention the duties of regional enterprise managers, who were supposed to draw up lists of employees, monitor their arrivals at voting stations, and submit turnout data to local administrators by 4 p.m. on Election Day. Thus, the Kremlin created a new infrastructure of employers’ and local government administrators’ responsibilities for people’s participation in elections.

Independent observers reported the mass effect of organized voting at polling stations. To control their participation, people were forced to change which polling station they visited, some were brought to stations on buses, some enterprises announced that Sunday was a “work day” (in order to make sure they showed up to vote), and, as observers reported, people en masse photographed their ballots to have proof of their voting participation for their supervisors.

It is difficult to credibly assess the scale of the “compulsory voting” scheme. But so-called “early voting” numbers on election day provide some indirect evidence. Observers remarked that there was unusual overcrowding at voting stations during the morning hours. For instance, the Central Election Committee reported at noon that turnout was about 5.5 percent higher at that point than in the 2012 elections. In some regions, the peak “early turnout” occurred at 3 pm. Taking into consideration that expected turnout was projected to be lower than it was in 2012, the effect of early voting may be even higher, up to 7–8 percent of all registered voters. In other words, from six to nine million more voters than expected came to polling stations in the early part of the day. Basically, this indicates that as part of the Kremlin’s “five-touch system,” employers were obliged to make sure their staff voted and they had until 4 pm to report the turnout of their employees.

Administrative Mobilization Instead of Political Mobilization

Broadly speaking, the “compulsory voting” system demonstrates the new quality of authoritarian institutions in Russia. First, before, people’s decision to vote was not a matter of administrative control. Second, previously, the Kremlin did not steadily push for a centralized administrative-corporate voting machine (consisting of local administrators and owners/managers of large enterprises). The “five-touch” voting control system essentially “de-privatized” the regional electoral machines that had earlier been the exclusive responsibility of governors, as regional politics specialist Alexander Kynev points out.

“Compulsory voting” methods differ from ballot-stuffing maneuvers. It is not about direct state coercion but “soft enforcement” whereby voting becomes a matter of corporate loyalty. People were not forced to vote for a particular candidate, but a certain politically loyal bias was present due to the fact that voters often had to submit to their employers a picture of their ballot as proof of participation.

The main aim of the Kremlin was not to force people to vote for Putin but to participate in the election. Not more than 50–55 percent of voters in “Russia-1” and “Russia-2” voted in the previous 2012 presidential elections. Some of those non-voters did not vote because they had not seen any appropriate alternative candidate (so-called ‘informed indifference”) but most did not vote because of low awareness of, and involvement in, any political agenda. Among this group are the less educated and lower qualified employees of large industrial enterprises. These people might be bound by corporate pressure but are indifferent to political participation because they do not see how elections provide accountability over the authorities (so-called “uninformed indifference”). There are also cases of people from “Russia-3” residing in “Russia-1” or “Russia-2” areas, which affects voting participation and patterns. The nub is that the Kremlin managed to replace contingents of “Russia-1” and “Russia-2” non-voters (those on so-called “voters’ strikes” who did not vote to express their protest against a non-competitive and unfair election) with those who usually do not vote because they tend to be “unaware” and “uninvolved.”

Certainly, a variable to take into consideration was Putin’s sluggish election campaign this time around, which supports the notion that administrative mobilization rather than political mobilization was used. Putin did not really conduct an election campaign at all this time. For example, Golos observers noted that there was hardly any television news coverage of Putin campaigning.

It is noteworthy that Putin did not undertake any foreign policy actions in the key pre-election timeframe, nor did he highlight any other foreign policy courses, as a way to increase political mobilization. It appears that the Kremlin’s opportunities for this kind of mobilization are exhausted. As a January 2018 Levada Center survey found, the main answer to the question of: “What is the biggest obstacle to the successful development of the country?” was: “Authorities give too much attention to foreign policy issues and not enough to domestic ones” (31 percent of respondents chose this answer, followed by “corruption” at 18 percent). Therefore, a traditional political campaign focused on a “rally round the flag” mobilization effect would have probably annoyed people and not been productive.

Conclusions

In sum, “abnormal voting,” interpreted as falsification using the Shpilkin method, provided over 8.5 million votes for Putin. Without these manipulations, the vote for Putin would have been about 70 percent with a 55 percent turnout. While these numbers would make for a convincing victory, it would be a repetition of similar victories—Putin in 2004 and Medvedev in 2008—but with lower turnout, which would have jumpstarted expert and societal discussions about the reasons voters were “de-mobilized.” It seems that the Kremlin felt the lower, actual numbers, would have been insufficient for the extra-legitimacy that Putin needs as he confronts the challenges ahead of international isolation, economic stagnation, and a transition of power.

The recent election demonstrates that there is a strengthening of authoritarian institutions taking place in Russia as Putin enters his fourth term. New techniques of manipulation were used in addition to some of the old ruses, but foreign policy actions were not used to get out the vote. The Kremlin coordinated with regional/local administrations and with the heads of major enterprises to organize systems of “compulsory voting” primarily via citizens’ employers. Thus, it resolved the unfeasibility of mobilizing on foreign policy issues by applying purely administrative mobilization procedures at the workplace.

Kirill Rogov is Senior Research Fellow at the Gaidar Institute for Economic Policy and Political Analyst at the Liberal Mission Foundation, Moscow.

[PDF]

Also see: Putin’s Reelection: Capturing Russia’s Electoral Patterns: A Discussion with Kirill Rogov, Point & Counterpoint, June 7, 2018.

[1] See: “Phantom voters, smuggled ballots hint at foul play in Russian vote,” Reuters, September 20, 2016; Alena Sadovskaya, “Vydumannye rezul’taty” (“Fictional Results”), Kavkaz Realii, March 19, 2018.

[2] Approval rating figures are from the Levada Center’s monthly Currier Survey.

[3] See: Kirill Rogov, “Public opinion in Putin’s Russia. The public sphere, opinion climate and authoritarian bias,” NUPI Working Paper No. 878, 2017; Kalinin Kirill, “The social desirability bias in autocrat’s electoral ratings: evidence from the 2012 Russian presidential elections,” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, Volume 26, 2016.

[4] See: Dmitry Kobak, Sergey Shpilkin, and Maxim S. Pshenichnikov, “Statistical anomalies in 2011–2012 Russian elections revealed by 2D correlation analysis,” physics.soc-ph, May 17, 2012; Sergey Shpilkin, Alrxander Kynev, Gleb Pavlovsky, and Kirill Rogov, “Anatomiya Triumfa,” Inliberty, March 27, 2018.