The Russian invasion of Ukraine sent ripples through the Caucasus, where frozen conflicts linger in Georgia and its breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which have been controlled and recognized as independent by Russia since 2008. The political repercussions of the war resonate, affecting the tenor and content of political discourses and decisions across the region. Preoccupied with its attack on Ukraine, Moscow slightly loosened its grip on South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Irredentism developed, of which the postponement of a referendum in South Ossetia in May to join Russia has been the most important political event. This action provoked an official statement from the Abkhazian leadership rejecting any possibility of Russia’s annexation of Abkhazia, or reintegration with Georgia for that matter.

With Moscow embroiled in war and stress, regional stability may be disrupted, and the United States, Georgia’s ally, may become more involved, perhaps echoing the Ukraine context. Already, in response to the possibility of a Russian annexation in the region, the U.S. Embassy in Tbilisi issued a statement reiterating Washington’s “strong support for Georgia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity within its internationally recognized borders.” This begs the question: What are the similarities and differences between Moscow’s conflicts here and its war on Ukraine? Both involved premeditated and direct military attacks. To be sure, the main similarity has been President Vladimir Putin’s desire to keep territorial disputes alive to prevent former Soviet republics from gravitating toward the EU and NATO. The main difference is that Russia did not annex any Georgian territory, as it did in Ukraine, and local elections have produced fairly elected Abkhazian and South Ossetian leaders, whereas Moscow appoints the leadership in its Ukrainian-occupied territories.

2022 Russia-Ukraine War vs. 2008 Russia-Georgia War

In its Ukrainian and Georgian wars, Russia prepared, advanced, invaded, occupied, and then recognized the independence of the breakaway territories or annexed them. However, there are distinctions and chronological differences. The 2022 Russian recognition of Ukraine’s Donetsk and Luhansk regions took place just before the Russian invasion, serving as a pretext for the war, while the 2008 recognition of South Ossetia and Abkhazia took place at the end of the war, as an outcome. The 2014 annexation of Crimea took place after the Euromaidan revolution that ousted president Viktor Yanukovych and involved Russian troops. The main difference was Russia’s quick victory in 2008 over Georgia in contrast to its unsuccessful 2022 blitzkrieg in Ukraine.

Washington has avoided direct participation in both conflicts, concerned about escalation and the possibility of Russia’s use of nuclear weapons. In terms of the U.S. role, both wars included imposing U.S. sanctions against Russia, supporting Georgian and Ukrainian territorial integrity, and providing weapons to both. However, in terms of the main differences, Washington has given far more weapons to Ukraine than Georgia, and it has imposed far more severe economic sanctions on Russia in 2022 than it did in 2008 (see Table 1).

Table 1. Similarities and Differences in Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine and Georgia

| Ukraine | Georgia | |

| Russia | ||

| The Kremlin openly prepared its invasion in advance, including by handing out Russian passports in the region | Yes | Yes |

| Russia occupied the breakaway regions | Yes | Yes |

| Russian troops reached the capital but failed to take it | Yes | Yes |

| There was fear of Russia using nuclear weapons | Yes | Yes |

| Russia recognized the breakaway territories | Before invasion | After invasion |

| How long the war lasted | Months or more | Five days |

| Russia annexed a breakaway territory | Yes | No |

| United States | ||

| The US acted as an ally of the invaded country | Yes | Yes |

| Economic sanctions on Russia | Massive | Limited |

| U.S. and NATO military help | Defensive: provided defensive weapons | Offensive: sent battleship to Black Sea |

On the ground, both Georgia’s and Ukraine’s breakaway regions announced their independence and/or expressed willingness to join Russia, but they differ ethnically, politically, and internationally. While Ukraine and Russia fight in Crimea, Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson over land and the East-West orientations of the predominantly Slavic people, the Ossetian and Abkhaz populations are ethnically distinct from both Georgians and Russians.

Internationally, six countries recognized the independence of Abkhazia and three recognized South Ossetia, while no UN member state apart from Russia has recognized the newly annexed Ukrainian territories. Also, Abkhazia came to officially oppose the idea of its annexation by Russia, while the Ukrainian breakaway regions’ Moscow-appointed leaders confirmed their will to join Russia. Additionally, Abkhazia was reluctant to recognize the independence of the Ukrainian breakaway regions but did (See Table 2).

Table 2. Similarities and Differences between Russia-Supported Breakaway Regimes in Ukraine and Georgia

| Ukraine | Georgia | |

| Russia occupied the breakaway regions | Yes | Yes |

| Breakaway regions announced independence | Donetsk 2014 Luhansk 2014 | Abkhazia 1999 South Ossetia 2008 |

| Breakaway regions proposed to join Russia | Yes | South Ossetia 1992 and 2006 Abkhazia 1995 |

| Georgian breakaway regions recognized by other breakaway regions | Yes: in 2014 | Yes: in 2006 |

| Ukrainian breakaway regions recognized by other breakaway regions | Yes: in 2014 | South Ossetia: in 2014 Abkhazia: in 2022, after Russia’s all-out invasion |

| Other countries recognized breakaway regions | No | Yes |

| There is a large Russian or Ukrainian ethnic population in the breakaway region | Yes | No |

| Russia annexed a breakaway territory | Yes | No |

| Russian controls the regional elections | Yes | No |

| Breakaway regions trying to establish relations with countries besides Russia | No | No: South Ossetia Yes: Abkhazia |

| Breakaway regions proposed to join the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) | No | No: South Ossetia Yes: Abkhazia 1993 |

| Breakaway regions proposed to join Russia as an independent associated member | No | No: South Ossetia Yes: Abkhazia 1991 and 2001 |

South Ossetian and Abkhazian Reactions to the Russian Invasion of Ukraine

Russian actions in and around Ukraine reverberated in Georgia’s breakaway territories, eliciting distinct reactions concerning regional security issues.Both Abkhazia and South Ossetian officials have demonstrated pro-Russian positions since the beginning of the war. However, the initial official statements from the regions slightly differed in timing and style. Sukhum(i)[1] selectively used Kremlin propaganda and avoided radical anti-Georgia and anti-Ukrainian terminology, as well as stressed regional interests. For its part, Tskhinval(i) fully re-enforced Kremlin propaganda, pushing radical anti-Georgian and anti-Ukrainian messages while also promoting upcoming local presidential elections.

Compared to Tskhinval(i)’s overeager attitude, Sukhum(i)’s actions were more self-restrained in recognizing Luhansk and Donetsk and seeking changes in economic relations with Russia. Also, the Abkhazian leadership was more careful in offering military assistance to Russia and never provided it, while South Ossetian leaders organized volunteers dispatched to the war under the South Ossetian flag, though these later deserted and returned home, causing a political scandal. Both regions have hosted refugees from Ukraine’s breakaway regions.

When the war commenced, South Ossetia and Abkhazia also expressed concerns about and took measures against a possible effort by Georgia to militarily restore Tbilisi’s control over the regions. Later they assessed the threat of what they call a Georgian invasion as low, allowing part of the Russian occupational forces to relocate to Ukraine.

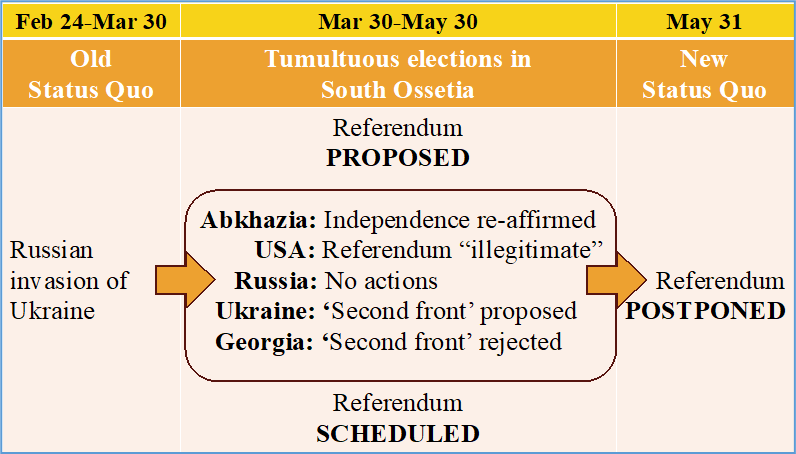

Moscow’s decision to organize a referendum in the occupied Ukrainian territories to join Russia created waves in other breakaway territories. On March 27, 2022, Luhansk leader Leonid Pasechnik announced a referendum on joining Russia, but later that day clarified that he misspoke. Meanwhile, Donetsk leader Denis Pushilin made a statement that his territory should join Russia, but not before the end of the ongoing military actions. Echoing the Ukrainian breakaway regions, on March 30, Ossetian leader Anatoli Bibilov proposed a referendum to join Russia, but the statement was received with mixed responses domestically. Bibilov argued that joining Russia would have two strategic benefits for South Ossetia: resolving its economic problems and becoming a step toward future unification with Russian-run North Ossetia into one region (called Ossetia-Alania), although the Kremlin never responded positively to any of those proposals (see Table 3).

Bibilov lost his reelection bid in May 2022 after a five-year term, and the new South Ossetian president, Alan Gagloyev, postponed the referendum indefinitely. While the South Ossetian proposition to join Russia was pending, it forced Abkhazian President Aslan Bzhania to denounce the possibility of Abkhazia following South Ossetian steps and to state that Abkhazia would remain an independent country in its relations with Russia.

Table 3. South Ossetian Referendum Turmoil in 2022

When Russian formalized its annexation of Ukrainian territories on September 30, the Abkhazian and South Ossetian presidents both reacted positively, promptly congratulating the pro-Kremlin leaders in Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson. The only difference between the two Caucasian addresses was that Abkhazia’s Bzhania talked at the same time about the independence of his territory on that same day, September 30, which is Abkhazia’s Day of Independence.

Future Trends

The Russian-Ukrainian war disrupted dynamics in the South Caucasus region. It highlighted Abkhazian insecurities, making them publicly reject the idea of a Russian takeover, and it triggered a South Ossetian referendum proposal and a postponement to join Russia. Altogether, a somewhat new status quo took hold in the region with the following characteristics:

- Russian reluctance to annex Georgia’s breakaway regions.

- South Ossetian preference for joining Russia and disinterest in improving its relationship with Georgia.

- Abkhazian preference for independence and openness to improving its relationship with both Georgia and Russia.

- Georgian commitment to non-military means in its ties with the breakaway regions.

- Reaffirmed U.S. support for Georgia’s territorial integrity.

This status quo will likely last until the end of the Russian-Ukrainian war unless interrupted by a dramatic change (see Table 3). Russia’s efforts to preserve the status quo in South Ossetia and Abkhazia might initiate the process of their reintegration with Georgia economically, though Russian political influence will remain an external factor out of the control of Tbilisi. Preserving the status quo is very likely for Abkhazia, reinforced by the fact that Abkhazian law now allows Georgian Abkhazians to receive citizenship (among cooperative ideas in healthcare and economics). Maintaining the status quo in South Ossetia is also more likely now that the project of a referendum on joining Russia has been canceled. Finally, any Georgian reintegration with South Ossetia and Abkhazia would be enhanced by resolving the problem of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), providing “broad autonomy,” and making economic investments.

Conclusion

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has invigorated Washington’s concerns about Moscow’s views and violent actions toward post-Soviet states and peoples. This is salient, considering that the territorial integrity of Georgia remains a U.S. foreign policy regional priority. Any Russian, homegrown, or U.S. action could contribute to more strife, the status quo, or even Georgian territorial reintegration. We may see a revival of Tbilisi’s “broad autonomy” proposition for Abkhazia (with some Western support) or a renewed Tbilisi effort to join the EU and/or NATO. However, any encouragement of military actions by any side would probably lead to discord, and it is unlikely the United States would openly interfere, harkening to Moscow’s goals in feeding territorial disputes. Nonetheless, Georgian membership in the EU and/or NATO would provide the people in South Ossetia and Abkhazia with better choices, such as between achieving higher living standards and higher security if they “integrate” with Georgia versus remaining in isolation and stagnation under Russian occupation.

[1] The terminology reflects both Georgian and Abkhazian/South Ossetian spelling to indicate the politically charged language use in the former Soviet Union.

Sufian Zhemukhov is Associate Research Professor of International Affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs at the George Washington University.