A Schizophrenic Mixture of Repression and Appeasement Marks Executive Succession In Kazakhstan

On June 2nd Kassym-Jomart Tokayev was inaugurated the second president of Kazakhstan. After Nursultan Nazarbayev resigned his post on March 19, 2019, acting interim president and long-time loyalist Tokayev run against six opponents. The list of presidential candidates included a woman, an opposition journalist, a communist, a trade union leader, an agrarian party candidate, and an ethno-nationalist. Throughout the campaign, the candidates avoided divisive social issues, such as staggering inequality, rural poverty, and the bilateral relationship with Russia. The government banned independent opinion polls, which made it impossible for analysts to assess the popularity of candidates and preempted the opposition’s attempts to coordinate the protest vote.

According to the Central Electoral Commission, Tokayed received 70% of the popular vote. The second-place contender, journalist Amirzhan Kosanov, congratulated Tokayev on his victory before the election official announced the final vote tally, a move that frustrated government’s critics and alienated Kosanov’s supporters. Despite the record numbers of independent election observers, social media and internet-based news sources reported significant violations, including ballot stuffing, intimidation, and forgery. Unsanctioned rallies and protests that took place on June 9-12th were quelled by an overwhelming show of force and the indiscriminate arrests of protesters and bystanders. At face value, elections were a simple formality in the government-orchestrated power succession. Yet there is strong evidence that the government took this election quite seriously, perhaps more seriously than most observers would agree. Indeed, Tokayev’s government employed a wide array of measures to stay in power by searching for new sources of legitimizing this exclusionary political regime.

A New Repertoire of Kazakh Electoral Authoritarianism

The 2019 elections were unprecedented in many aspects: for the first time, Nursultan Nazarbayev, who had occupied the chief executive office since late Soviet times, was not on the ballot. The electoral campaign was marked by explicit efforts to demobilize the electorate. This departs from the previous practices of pro-regime mobilization. The public received mixed signals about the limits of political expression that the government was willing to tolerate. This preempted heated policy debates but empowered independent domestic civil groups to organize effective monitoring in about 20 percent of pooling stations nation-wide. On June 14, civil groups announced they will challenge election results in court. According to observers, officially reported votes for Tokayev largely overstated his documented support at the voting booths. Despite a few reports that western provinces, in fact, had close elections, there is no indication that Tokaev’s opponents had a real chance of beating him at the polls. With the government’s tight control of information, lack of organized opposition, and a general sense of political apathy on the part of the population, the abuse of the electoral process looks quite unnecessary. Election officials inflated Tokayev’s vote to avoid the second round which would create additional opportunities for popular mobilization. Elections were rigged not to secure Tokayev victory, but to ensure his win by a large margin.

Preemptive Measures to Ensure Tokayev’s Victory

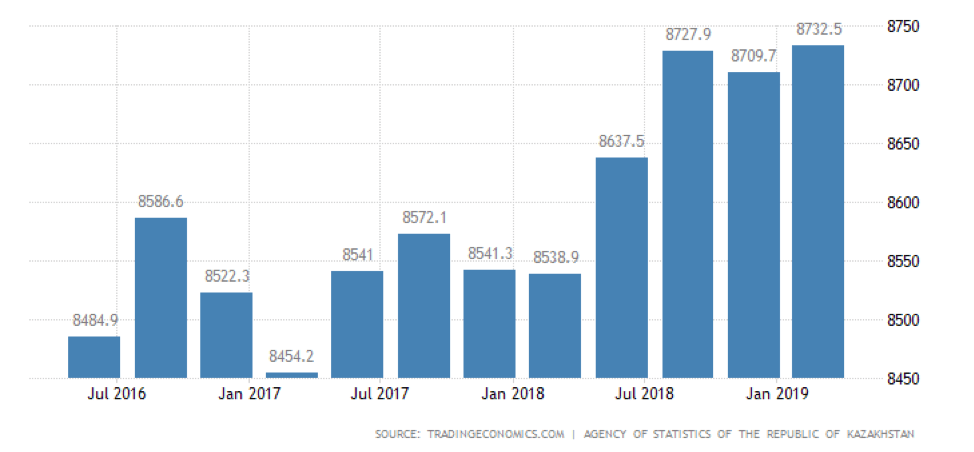

As with the previous elections, in 2019 Kazakhstan relied upon policy mechanisms to improve economic conditions leading up to the elections. Recent research shows that incumbents holding elections in authoritarian regimes might use government policy to manipulate economic conditions. Masaaki Higashijima, for example, analyzed 131 electoral autocracies and concluded that authoritarian leaders “hold manipulation of economic policy in their toolbox” to “convey a credible signal of their ability to mobilize popular support.” Kazakhstan’s short-term economic statistics reveal that the electoral campaigns coincided with nontrivial decreases in unemployment and inflation. According to the Statistical Agency of RK, the number of employed persons in Kazakhstan increased by 22.8 thousand or ¼ percent of total employment in the first quarter of 2019 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Employed Persons, Thousands

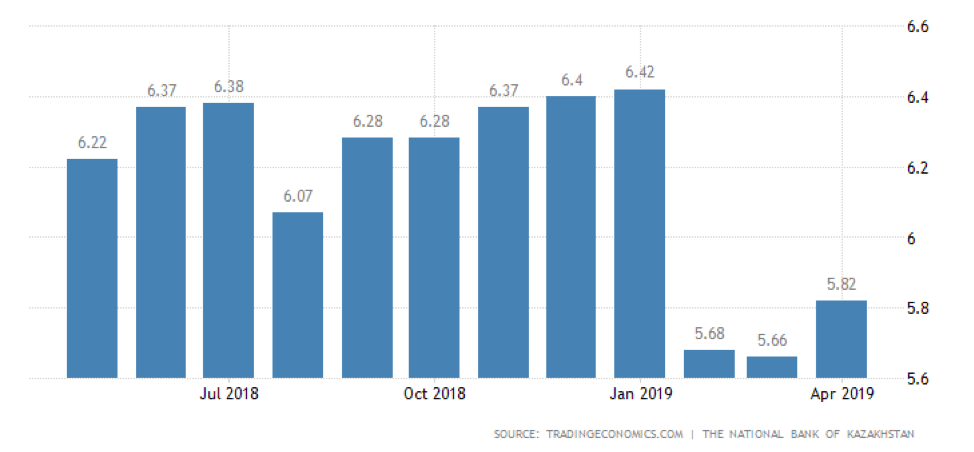

Total employment increased 2.3 percent from the same period in 2018. Moreover, the rate of inflation reported by the National Bank dropped from 6.42% in January to 5.8% in April (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Kazakhstan Core Inflation Rate, %

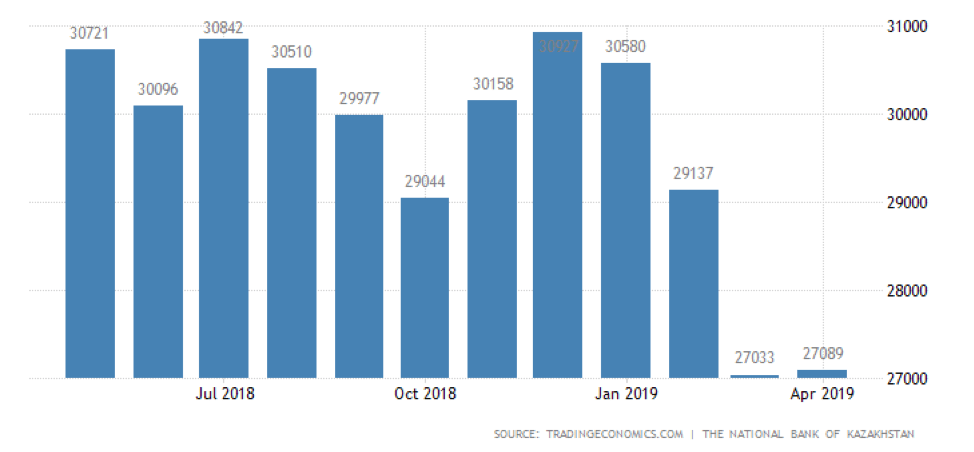

As with any other short-term election-related government policies, these improvements likely resulted from the boost in short-term government spending. The observed drop in currency reserves held by the National Bank (Figure 3) indicates this is likely the case.

Figure 3: Foreign Exchange Reserves in Kazakhstan, USD Million

Maintaining Authoritarian Rule After Nazarbayev

The government’s disproportionate use of repression prior and following these elections suggests that the regime was not confident in the effectiveness of its censorship, fraud, and economic policy tactics. After Nazarbayev’s resignation in March, police quelled a number of citizen’s protest. The official state media was not shy reporting detentions of protestors and lawsuits against activists, signaling that a much-awaited political liberalization is not happening. After elections took place, the government-banned Democratic Choice of Kazakhstan (DCK) party and civil activists called protest rallies in Almaty and Nursultan. Despite their modest size and peaceful nature, protests were met with a massive display of force. The June 12th protests had been preempted by closures of businesses and public venues, police blockade of Nursultan, and armed military vehicles in Almaty. Military and police forces largely outnumbered protestors and were called in preemptively with no protest activity in the site. Electoral fraud and excessive show of force had contributed to the public’s frustration with the newly elected president.

These schizophrenic tactics of Tokayev’s government show that in the period of executive succession Kazakhstan’s authoritarian regime is searching for new sources of legitimacy. Nazarbayev’s rule was maintained by limited uses of violence thanks to his cunning political tactics, personal charisma, and cult of personality. Nazarbayev’s exit from power requires finding new ways of legitimizing the regimes’ exclusive claims over the distribution of natural resource wealth and growing social inequality. Its attempts to boost the economy and demobilize the public prior to elections and its resort to electoral fraud and repressive measures suggest the government is not confident in its ability to seamlessly transfer presidency from Nazarbayev to his successor.