(PONARS Policy Memo) For Georgia, the enacting of an Association Agreement with the EU in the summer of 2016 was a pivotal moment in cementing its strategic bonds with Europe. The agreement, which lowers trade barriers and promotes democratic reforms, undeniably marks an important course for Georgia’s foreign and security policies. However, even as officials in Tbilisi talk about the irreversible nature of Georgia’s Europeanization, Georgia-skepticism exists among some EU member states, stalling Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic integration and moderating its European ambitions. Rather than pinning the blame for this on the Europeans, Georgia should acknowledge it did not work hard enough on building ties over the past decade with European partners that same way it did with the United States. While close relations with Washington are essential, Tbilisi needs to be proactive with specific EU member states to help them overcome any lingering reservations. Specifically, Georgia must consolidate its links with Germany, the country that has the most persuasive powers in European affairs.

Two Images of Germany: Reliable Partner and Spoiler of Dreams

Georgians have a built-in understanding of how the Ukrainians feel living under Russian pressures and they see in a positive light Germany’s efforts trying to end the Donbas conflict. Chancellor Angela Merkel faces new elections in September 2017, while in the United States, a new administration came to power that heralds (apparently) a more isolationist policy in global affairs. Thus, with the possible “withdrawal” of the U.S. presence in the region, it would be wise for Tbilisi to pay more attention to Germany’s perceptions and inclinations.

Georgia and Germany have had very good cultural, economic, and political ties for two centuries. This year, Georgia will hold festivities for the 200th anniversary of the first German villages settled in Georgia. Germany was the first European country to recognize Georgia after it gained independence in 1991 and to establish an embassy in Tbilisi. During Georgia’s civil war at the break-up of the Soviet Union, Germany was one of the first countries to provide humanitarian aid and support for reconstruction. Relations were especially close during former Georgian president Eduard Shevardnadze’s term. A former Soviet foreign minister who played a prominent role in the reunification of Germany, Shevardnadze had a special “German connection” with former German leaders Helmut Kohl and Hans-Dietrich Genscher. Berlin also showed consistent support and solidarity for Georgia in the aftermath of Russian aggression in 2008, as well as during the process of negotiating, signing, and ratifying Georgia’s Association Agreement with the EU.

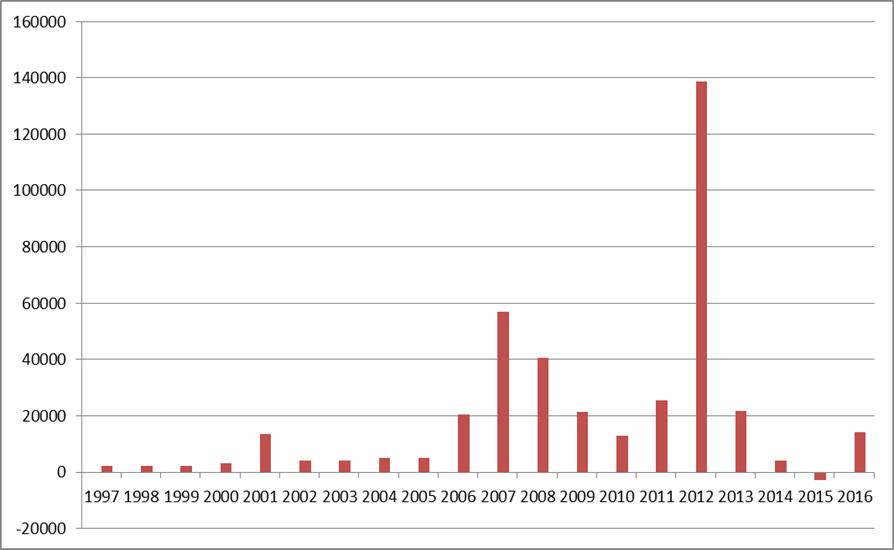

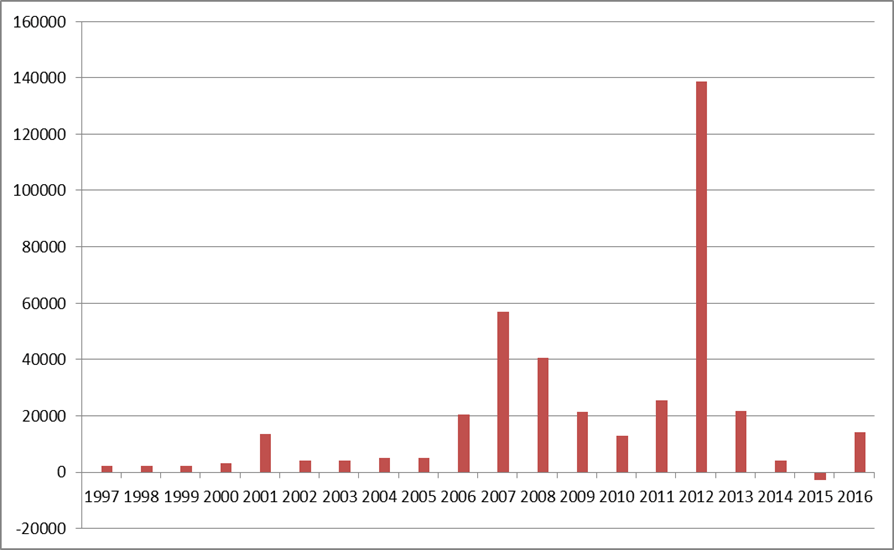

Both Germany and the United States have become the main international guarantors of Georgia's sovereignty over the last two decades. Overall, Germany is currently Georgia’s sixth-largest trading partner and is interested in diversifying its energy routes, including through the East-West transport and energy corridor. Interest in Georgia's investment environment should not be underestimated. In 2015, trade between Germany and Georgia amounted to about $480 million. Georgia has often been a recipient of high levels of German Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. German FDI in Georgia (US$, 1997-2016)

Source: National Statistics Office of Georgia

As high-level bilateral relations strengthened, it was anticipated that trade relations would transform into a strategic relationship similar to the U.S.-Georgian partnership. Germany was expected to become a political patron for Georgia’s quest for Euro-Atlantic integration. However, this did not come to pass. After the departure of Shevardnadze from Georgian politics, the Tbilisi-Berlin nexus weakened. As it turned out, bilateral relations were based mostly on personal relationships and had never been meaningfully institutionalized. As a result, while formally maintaining good working contacts, Georgian-German political relations in recent years have fluctuated, with both experiencing sharp Russian pressures.

Russian-Georgia Conflict and Downgrade of Bilateral Relations

Starting in 2005, amid Georgian-Russian antagonisms, Germany’s relations with Georgia markedly downgraded. The decline was precipitous but it did not occur suddenly. Georgia’s Rose revolution, with Mikhail Saakashvili enjoying strong support from the George W. Bush administration, drastically changed Georgian foreign relations, pushing for a more ideological and less pragmatic policy.

Under Saakashvili, Tbilisi was in the U.S. basket and neglected its European partners, including Germany. The country made a strategic miscalculation believing that if it could garner U.S. support for Georgia’s integration into NATO, then other Western allies would follow suit and automatically support Georgia’s case. However, the 2008 NATO summit in Bucharest confirmed this miscalculation, as Germany and France pressured NATO members not to offer a Membership Action Plan (MAP) to Tbilisi—effectively blocking Georgia from joining the Alliance. While Berlin argued that such a step was necessary to decrease friction with Moscow, Europe’s rejection may have emboldened Russia to “invade” Georgia because it exposed Western timidity.

The stunned silence in Berlin following the war in Georgia was a huge blow for bilateral relations and for Georgia’s transatlantic ambitions. Berlin not only refused to punish Moscow for its military aggression, it put forward what it dubbed a “modernization partnership” only weeks after Russia illegally recognized Georgia’s breakaway regions. As public opinion in Germany tilted toward the Russian version of events, Georgia perceived that Germany was pacifying Moscow’s neo-imperial instincts. Of course, Tbilisi realized that German politicians and businesspeople had close relations with Russia and its lucrative market opportunities—and that these aspects were more important to Berlin than a tiny Black Sea country with unclear European allegiances.

After the Russia-Georgia conflict, bilateral relations suffered from misconceptions about each other’s behavior. Georgians saw Germany as a reluctant partner or spoiler, partly influenced by a Russia-first policy. About 30 percent of the natural gas in the German market is imported from Russia. Former German chancellor Gerhard Schröder’s 2005 acceptance of Gazprom’s participation in the Nord Stream project (a pipeline between Russia and Germany) showed Germany’s “commitment” to Russia, further leading Georgians to question Germany as a reliable, strategic partner. Moreover, Germany’s skeptical stance about NATO enlargement reinforced this impression, on the part of Georgian elites, that even if Saakashvili’s liberal reforms were well received, no one in Europe was ready to risk war with Russia on behalf of Georgia’s transatlantic aspirations.

With the accession to power of the political coalition Georgian Dream in 2012, bilateral relations became more stable. The Dream’s pragmatic policies and more accommodating approach toward Russia was a better fit with Berlin’s strategic interests. The new Georgian government also maintained a strategic partnership with the United States, but believed, at the end of day, that Georgia should join the EU, so Tbilisi started to cultivate a more EU-centered foreign policy. Hence bilateral relations became more intensive, including high-level visits between Germany and Georgia.

Georgia’s deepening relations with Germany had special importance in the context of implementing the Association Agreement with the EU and the substantive package that was at last offered by NATO. However, it was Germany that reportedly took the lead in 2015 in delaying the agreement on easing Schengen-zone travel requirements for Georgians. Even though Georgia had fulfilled all of the EU Commission’s technical demands, Germany cited a crime spree as the reason for waiting.[1] This resulted in Georgians having lower levels of trust in Berlin and, more generally, a rise in Euroscepticism in the country.

Moving Forward: Managing Expectations

Germany’s support of Georgia is essential for its progressing integration with the EU and with NATO. Georgian elites still have to make better inroads with Berlin’s policymakers. Even though Tbilisi seeks a closer relationship with Germany and aspires to become a full-fledged member of both the EU and NATO, it is not clear that Germany is prepared to take a dedicated role in upholding Georgia’s objectives. On May 21, 2015, Merkel stated at the Bundestag that the Eastern Partnerships are “not an instrument of the EU’s enlargement policy,” adding that the EU should not trigger false expectations for its eastern partners in this regard.

While Germany does not principally object to Georgia joining NATO, Berlin has no clear concept of how to deal with Georgia’s strategic aspirations to become part of Western institutions. Because Germany remains unconvinced about Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic future, especially in regards to granting Georgia a NATO MAP, it feels more comfortable in fostering sustainable economic development in Georgia and supports the long-term Europeanization of Georgia through various projects.

Tbilisi has Euro-Atlantic integration as its near-term objective. The long-term strategic decision to move closer to the EU and NATO is non-negotiable for Tbilisi and has the strong support of the Georgian people (NDI polls show about 72 percent of Georgians support closer ties with the EU). Furthermore, because Russia denies the European Union Monitoring Mission any access to Georgia’s breakaway regions, Germany’s continued support to the Mission is appreciated by the Georgian leadership. Tbilisi also expects unwavering support on initiatives to normalize relations with Russia, but not at the expense of compromising Georgia’s territorial integrity and sovereignty. Moreover, after a (generally) successful visa liberalization process with the EU, Georgians have the anticipation that they may be able to access the EU labor market, as it represents the main channel for immediate improvement in the life of ordinary Georgians.

Conclusion

German attention and support play an important role in Georgia’s Europeanization process. Berlin, together with its European partners, creates uncertainty about Georgia by exercising some ambiguity about the country’s European prospects. At the same time, Georgia’s government, think tanks, and academic communities are committed to Europe (for the most part) and therefore the onus is on Tbilisi to pay more attention to the Tbilisi-Berlin nexus, comprehend any German/European reluctance, and propose solutions to upgrade Georgia in the list of EU foreign policy priorities. While it remains to be seen what direction the new U.S. administration will take toward post-Soviet countries, strong transatlantic support could be crucial to revive a German-Georgian strategic partnership. If the new U.S. administration is particularly keen on sharing the burden of global crisis management, it could “outsource” some tasks to Germany, its most important partner in Europe, prompting Germany to take the lead in areas such as Georgia’s Europeanization project. The Georgian public sees Germany’s changing Russia policy as sobering, and they feel that Germany’s strong support for Georgia’s Western aspirations is essential, if not vital, for the future of their country.

Kornely Kakachia is Executive Director of the Georgian Institute of Politics and Professor of Political Science at I. Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University.

[PDF]

[1] Media reported that the reason Germany kept Georgia at arm’s length was because of the migrant crisis and criminal activities (burglaries) committed by Georgian nationals in Germany.