As Russia’s war in Ukraine raged last year, Russia and China were getting closer in trade and diplomacy. China’s trade turnover with Russia reached new highs, and China became one of the main destinations for Russian oil and gas. While Beijing has been turning down most of Moscow’s requests for supplies of weapons and munitions, it did provide diplomatic cover for Russia’s invasion. China has also proposed a vague “12-point” blueprint for terminating Russia’s war in Ukraine while trying to convince Kyiv and European capitals of the need for a peace agreement that would leave much of Russia’s Ukrainian acquisitions in the Kremlin’s hands. Yet, China’s mediation has not been outright rejected by Ukraine or the West. Indeed elsewhere, in March 2023, Beijing achieved a broadly recognized victory as a mediator, having successfully brokered the restoration of diplomatic relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

As many observers note, though, the war in Ukraine has served to highlight the confines of their expectations and limits of their partnership. China disavowed prior knowledge of President Vladimir Putin’s plan to attack Ukraine and has steadily refrained from throwing its full weight behind him. And Beijing has openly discouraged Moscow from contemplating the use of nuclear weapons. With casualties continuing to climb, in April 2023, the Chinese ambassador to the EU even downplayed the “no-limits” Sino-Russian partnership formula as a mere figure of speech. To what extent does rational calculus underlie pre-war and current discrepancies in their positions? Despite the mutual intention to connect more, we can see that much of the mutual disappointment results from the socio-cultural mismatch in Russian-Chinese bilateralism. While some research shows that the impact of their culture and identity differences has been minimal in some cooperative spheres, the respective leaderships and bureaucratic governments have well-known dissimilar aspirations leading to reoccurring mutual expectation failures.

Imperfect Friends

Signs of a less-than-perfect alignment between Moscow and Beijing have consistently lingered. Moscow has long sought a stronger commitment from China in support of its gambits vis-à-vis Washington and its allies—with China usually obliging rhetorically. Russo-Chinese partnership declarations seemed to get more far-reaching every year, while Putin and Xi appeared to exhibit increasing personal sympathy over time. China and Russia pursued the same strategic goals of counterbalancing the United States and its alliances in Europe and Asia, and the sides’ economic complementarity and political regime similarity were undeniable.

However, many of Moscow’s expectations were not being met by Beijing. China never recognized Russia’s annexation of Crimea or the “independence” of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. China did not publicly accept the Kremlin’s key justifications for the war against Ukraine, refused to provide it with weapons, and has not helped it evade sanctions. Beijing has very little enthusiasm for multilateral arms control efforts. Most surprisingly, Chinese companies have been reluctant to pursue strategic investment in the Russian economy beyond the oil and gas sectors—in contrast to major European firms that were prepared to invest in Russian infrastructure or purchase large amounts of natural gas from Russia before its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Speaking from over 50 years of international experience, Henry Kissinger, in April 2023, dramatized the puzzle of the Sino-Russian quasi-alliance by suggesting that he had “never met a Russian leader who said anything good about China” or “a Chinese leader who said anything good about Russia.” While hardly more than a figure of speech, Kissinger’s statement highlights the obvious fact that China and Russia represent two atypical civilizations—historically, linguistically, politically, and economically.

Compared to the links between the Arab world and China, for example, which have had multiple centuries of shared history, Sino-Russian interactions had been relatively minimal before the mid-19th century. Today, it is hard to find another extensive land border in the world that separates societies so differently on so many counts. It is, therefore, natural to consider the hard and soft identity discrepancies as the main sources of limitations on the Sino-Russian partnership.

The Impact of Culture

All in all, the culture-driven factors in their discussions and negotiations do not require justifications in terms of calculable costs and benefits. In contrast to a “rational” belief in a decisionmaker’s ability to calculate outcomes and the need to be guided by such calculus, culture is “sub-rational” in that it uncritically relies on tradition. From that perspective, trying to “calculate” makes little sense because the world is too complex, so we should instead stick to time-tested routines, even if they look suboptimal. Because the difficulty of prediction and the futility of rationality is hard to break or overcome, the impact of culturally determined factors may significantly impact all spheres of human activity, including interaction by representatives of different cultures through negotiation.

What is the record of interference of culture in Sino-Russian relationships and the limits it may have imposed on the rapprochement between Moscow and Beijing? A rare multi-year study by Tariq Malik at Liaoning University published in 2021 compared the Chinese and Russian styles of negotiation and showed that the two negotiation cultures were in no way incompatible or even substantively different. Apparently, Russian and Chinese negotiation styles converged on most key parameters, such as the proclivity of the sides to avert risk, proceeding from an agreement on general principles, avoiding emotionalism, and viewing negotiation as a win-win game. Both cultures considered negotiation primarily as a means of maintaining a positive dynamic in relations with counterparts—as opposed to the imperative of reaching a deal. The report showed that Chinese and Russian negotiators tended to diverge on informality in negotiation (the Chinese approach was more formal), with a greater preference for indirect communication on the Chinese side and the Chinese negotiators’ penchant for spelling out detail in agreements—as opposed to making deals on general terms.

In a linked dimension, it is worth exploring the impact of the core aspects of Chinese and Russian foreign policy identities on the potential for mutual understanding, trust, and deal-making. Identity pre-disposes a country for a certain—appropriate—behavior that may not be aligned or compatible with the preferred behavior patterns of that country’s prospective partners. For example, the U.S. identity as an economically effective liberal democracy proselytizing its successful experience worldwide proved to be incompatible with Russia’s post-Cold War identity as a personalist regime system exhibiting haphazard foreign policy behavior. This discrepancy in no way justifies Russia’s slide toward authoritarianism or its aggression against Ukraine but only illustrates the compatibility of core identity aspects in shaping inter-state relations.

Unlike America’s identity, the key aspects of China’s self-perception—leadership in the Global South and centrality in the Asia-Pacific—have not diminished the prospects for a quality Sino-Russian partnership. Moscow realized it would not be able to match Beijing’s economic promises to the developing world and refrained from direct competition. Instead, Russia capitalized on its longstanding partnerships with such majors as India or Brazil, while in Africa, Moscow focused on several key countries—for example, the Central African Republic or Libya—by offering their strongmen relatively inexpensive security deals and supplies of weapons (critical to the strongmen’s survival).

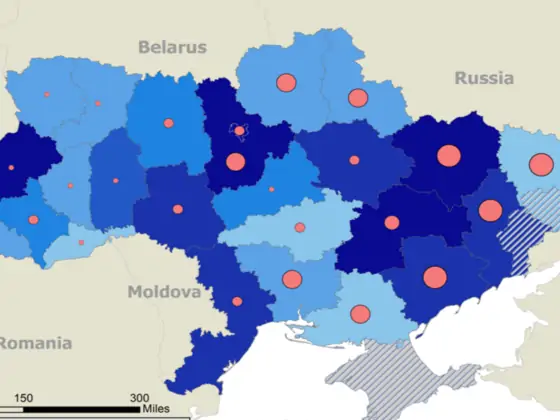

China’s quest for status as an indisputable leader and guarantor of order in Eurasia-Asia-Pacific has not been a poisoning ingredient in their bilateralism. We can recall that the Russian Empire annexed part of Chinese Manchuria in the late 1850s, but China’s reformist leader Deng Xiaoping decided to drop large-scale territorial claims on the Soviet Union. Instead, Deng focused on negotiating feasible small-scale border adjustments that allowed both countries to announce, by the mid-2000s, a final settlement of their bilateral territorial issues. The resolution of Sino-Russian border disputes was subsequently leveraged by pro-China public-relations campaigns in Russia. Public attitudes toward China among Russians thus improved dramatically: while in 1995, 21 percent of Russians had a “bad” attitude toward China, and only 48 percent had a “good attitude,” in December 2022, 6 percent had a “bad” attitude, and 87 percent had a “good” attitude.

A personalistic regime with its own sense of mission in foreign policy has been a constitutive part of both Chinese and Russian identity since at least the early 2010s. While Putin has been increasingly fixated on maintaining unchallenged influence over Ukraine and post-Soviet Eurasia, Chairman Xi stepped up efforts to assert China’s privileged status toward its Southeast Asian neighbors while extending “belts and roads” further afield. In pursuit of these costly objectives, both leaders tightened the screws domestically, quashing organized dissent, and carried out massive brainwashing campaigns.

Interestingly, over the last century, shared missionary authoritarianism identity has been conducive to rapprochement between Beijing and Moscow, the most notable example being a strong personal chemistry between the two totalitarian leaders, Mao Zedong and Joseph Stalin. In the words of Tong Zhao and Dmitry Stefanovich in an American Academy of Arts and Sciences report, “China has traditionally emphasized the importance of building trust through a top-down process.” Once Putin did away with the post-Soviet political reform momentum, mutual understanding and trust began to strengthen on a personal level between Putin and Xi. Authoritarianism so far has been the bridge bringing China and Russia closer together politically—even if it fails to unlock the full potential of bilateral, economic-focused engagement.

Calculated Self-Restraint?

While there has been little, if anything, in Chinese and Russian negotiation cultures or identities that should overly complicate their interaction, there has equally been nothing that should facilitate it. The actual limits on the partnership have been imposed by Russian and Chinese policymakers themselves.

First, it has long become common for Chinese businesspeople to consistently complain about Russia’s bureaucratic maze. While that maze is largely a result of rational bureaucrats eliciting bribes, it has also been abetted, if not blessed, by Russia’s top leadership. The Kremlin rationally calculates that reining in the bureaucracy would endanger the nationwide mode of governance, which provides loyal bureaucrats with a mandate to enrich themselves with impunity.

Second, while seeking to expand their influence on their respective neighborhoods, Moscow and Beijing have been operating on different schedules. Unlike Beijing, which aims to shift the global balance of forces by the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 2049, Putin’s Kremlin has been playing a shorter game. Moscow’s invasion planning horizon needed the West to accept Russia’s terms relatively quickly. Such divergence manifested itself in the Kremlin’s rushed and unexplained assault on Ukraine that appeared to have caught China unprepared. The difference in the two country’s approaches was documented already in the autumn of 2008 when, according to former U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, amidst a global financial crisis, Moscow proposed that Beijing sell large amounts of China-held U.S. treasury bonds—sparking immediate and massive financial turmoil in the United States. The idea fell flat on the Chinese leadership, given the high degree of economic interdependence between China and the United States.

Finally, a massive structural Chinese economic presence in Russia has never been politically acceptable to the Kremlin because it would entail a significant role for China in the Russian economy and politics. Such a scenario would endanger Russia’s notorious patronal system of governance, which requires a top-down distribution of benefits in exchange for loyalty. In this political framework, only the designated patron can be allowed to disburse benefits, while the existence of independent economic lobbies cannot be tolerated. Nonetheless, from a broad view, the war has already prompted articles about how Moscow is becoming a junior partner under Beijing’s clout.

On the Chinese side, the unwillingness to invest in Russia beyond oil and gas and some consumer goods seems to be a result of a deliberate choice of priorities. Top Chinese economic planners have never been impressed with Russia’s rates of economic growth and the prospects for its role in the world economy beyond supplies of raw materials. So far, China has prioritized investment in Europe, Southeast and South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East. Among other takeaways, it means that cultural or identity discrepancies have not impeded Chinese foreign investment anywhere, including Russia. Negotiating structural economic interdependence between China and Russia has been difficult mainly because of rational bureaucratic interests.

Conclusion

Overviewing the obstacles to Sino-Russia cooperation before and during Russia’s war in Ukraine highlights the general reason why authoritarian states find it difficult to engage in “deep negotiation” about far-reaching economic deals and alignments. Such deals either create unwanted autonomous centers of political and economic gravity within those authoritarian countries or compromise the ideological agendas that authoritarian leaders use to justify their rule. For example, how can Russia be “completely sovereign”—as its leaders have suggested it should be—if large investors from other countries are allowed to pull the strings in Russian economics and politics?

Finally—and relevant to the prospects of Sino-Russia relations beyond Russia’s war in Ukraine—there is likely a significant potential for economic engagement between Beijing and Moscow if Russia were to evolve toward a rule-of-law pluralistic society rather than a patronal national-security state. That potential may be unlocked once Russian bureaucracies see as their mission their country’s prosperity instead of self-enrichment and advancement of whichever policy their patrons fancy.

For many decades, it has been common among analysts globally to scare the United States and its allies with the strengthening of the Sino-Russian quasi-alliance: unless Washington becomes more attentive to Moscow’s interests and aspirations, Russia is going to fall irreversibly into China’s embrace. But in fact, what we have been observing so far have been suboptimal conditions for full-scale Sino-Russian economic engagement. Their interdependence may begin to flourish if there is at least limited political transition in one or both counterparts.

Mikhail Troitskiy is Professor of Practice at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.