Over the past half year, Russia-watchers have been parsing the country’s draw toward its Soviet past. Could an underlying part of this nostalgia involve the benefits of socialist economics? The older generations in Russia, Ukraine, and the rest of the former USSR, remember the reliable provision of wages, salaries, state stipends, and pensions. Despite its harsh downsides, the USSR did adhere to a socialist-rule-of-thumb that the income of the highest paid worker should be no more than ten times greater than that of the lowest paid. Vladimir Putin has at least paid lip service to a certain degree of income equality. The appeal of this—regardless of the reality—may be one driver of his popularity and the political movements we see in Crimea and eastern Ukraine. To better understand this, an element of economics should be re-visited: the merits of and relationship between “income equality” and “equal opportunity.” Vladimir Popov looks at the theory and evidence.

Market dynamics

There is a view that competitive capitalism left to itself without any government regulation can ensure a fair and stable distribution of income and an “optimal” degree of inequality. This concept assumes that all economic agents (the owners of labor, capital, land, and intellectual property) get remuneration equal to their marginal productivity, which results in social harmony. Only market imperfections, such as credit constraints and a lack of access to education, resulting in unequal opportunities, can create “unreasonable inequalities.”

Unfortunately, this is not the case. While unequal opportunities for individuals may be the primary reasons for income differentiation, there are others as well. Even if opportunities are equal for everyone, a market economy does not guarantee a stable and fair distribution of income. Left to itself, a market economy may drift toward ever greater inequalities, which is why we need special government efforts, policies, and oversights to cope with undesirable trends.

“Unequal opportunity” accounts for over 70% of income inequality

Branko Milanovic, a former World Bank economist and an authority on income distribution, estimated in 2008 that very basic and largely uncontrollable factors (i.e., country of residence and the income of your parents) determine 70-85 percent of the differences in individual incomes throughout the world, leaving very little flexibility for individuals to alter their fates.[1]

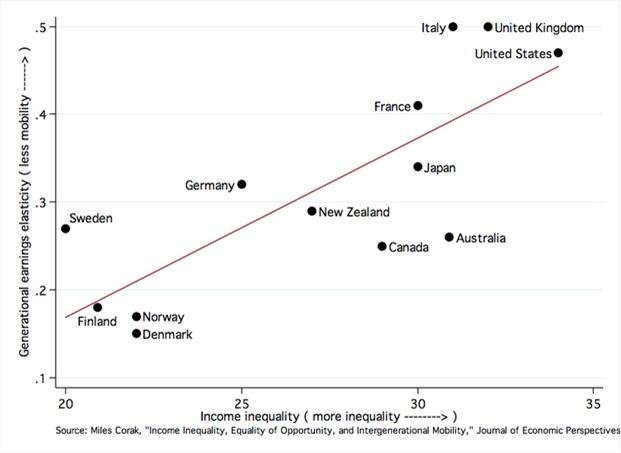

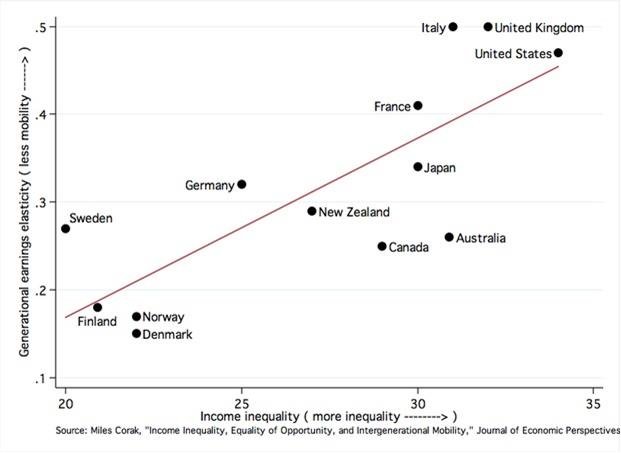

In 2012, Michael Corak, a labour economist, traced the relationship between inequality in income distribution (also known as the “Gini coefficient,” which measures inequality on a scale of 0-100 percent) and the correlation of income levels between parents and children. He drew a chart that later became known as the “Great Gatsby curve,” which shows that in unequal societies, children’s income levels are tied closely to the income levels of their parents.

Thus, inequality is self-perpetuating: for someone born into a poor family, the chances of escaping poverty are worse in those countries with a highly uneven distribution of income.

Fig. 1. The “Gini coefficient” and correlation between childrens’ and parents’ income in 1985

But even if all individuals had equal opportunities (equal starting positions, equal education, equal health, etc.), their income would still not be the same. Differences in income partially reflect differences in talent and job performance, but there are other factors as well.

Why identical twins have different incomes

“Why have you achieved more than others in life?” is a standard question often posed to celebrities. Their typical response usually includes a combination of genetics and hard work but also an acknowledgement that luck played a big role.

The idea of luck as a key factor can be examined through the case of identical twins. Identical twins have the same genes, were raised in the same families, and most likely had the same educational opportunities, but they often have very different lives—and incomes—later on and rarely die at the same age or of the same causes.

Therefore, even when “equal opportunity” exists, it does not mean that all differences in outcome are pre-determined. As Joseph Stiglitz wrote, “Markets, by themselves, even when they are stable, often lead to high levels of inequality, and outcomes that are widely viewed as unfair.”[2]

Equilibrium in the market emerges only due to deviations from the equilibrium, these deviations are a rule rather than the exception due to constant supply and demand shocks, and during these deviations producers could either receive windfall profits or be unable to recover costs.

Consider a shock, like the 9/11 terrorist attack, which greatly increased the demand for national flags in the United States. Flag prices increased, the producers of flags made high profits out of thin air, and patriotically-minded citizens were forced to pay high prices that were far higher than the production costs. Hardly any economist, even neo-liberal, would consider this fair.

Or consider the trend of inequality between producers over a period of time: large companies have the advantage of scale and scope and ceteris paribus (all things being equal) are better suited to surpass their competitors. From this perspective, the trend in the perfect free market would be to drift towards one huge super-company controlling everything with one individual controlling this company (ironically, this sounds like the socialist centrally planned economy). If it does not happen today, it is due to anti-trust legislation, progressive taxation, social programs, and other counterweighing policies.

Global secular patterns of income inequality

We are not sure why income inequalities grow. Simon Kuznets hypothesized that there is an inverted U-shape relationship between economic growth and inequality—it increases at the industrialization stage, when the urban-rural income gap rises, and declines later with the rise of the welfare state.[3]

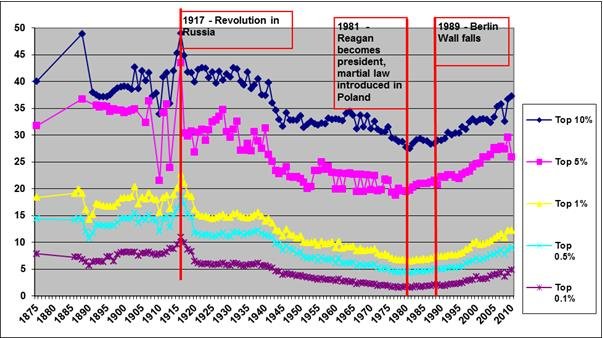

However, current empirical research does not find much support for the existence of Kuznets’ curve. The long term dynamics of inequality seem to be such that it increased between the years 1500 and 1900, probably reaching an all-time peak in the early twentieth century (fig. 2) and only started to decline after WWI and the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the 1980s, it then again began to rise (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Income shares of the top 10, 5, 1, 0.5 and 0.1%, average for 22 countries[4]

Source: Facundo Alvaredo, Anthony B. Atkinson, Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, The World Top Incomes Database, http://g-mond.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/topincomes, April 25, 2012.

Thomas Piketty, author of Capital in the Twenty-First Century, a 2014 bestseller about global inequality, argues that the tendency of “inequality” to rise is because the rate of profit is higher than the rate of economic growth. He believes that rising inequality is a long term (and ongoing) trend caused by an increase in the ratio of wealth (capital) to output—this has been labeled as “patrimonial capitalism.” (I will provide a critique of Piketty’s arguments in an upcoming comment on this site.)

An alternative but compatible view is that these dynamics of inequality were actually caused by the 1917 revolution in Russia and the emergence of the USSR and other socialist states. Why? Socialism had free education and free healthcare with very low income inequalities. This system acted as a counter to global capitalism, especially between 1917 and 1982, when the global socialist system was relatively dynamic and it was catching up with the West in terms of economic indicators. When socialism lost its dynamism during the 1970s and finally collapsed, the inherent growth of income inequality in capitalist states resumed.

Either way, it does not look like long term trends in inequality can be explained by unequal opportunities alone.

In conclusion

The perception of fair, justified, or reasonable inequality in income distribution is very much a matter of judgement in different times, nations, and cultures. Still, I would say, to ensure fair income distribution we need to rely not only on the equalization of opportunities hoping that perfect markets will take care of the rest, but on special government actions—from, to begin with, progressive taxation to stimulating workers' participation in corporate ownership and profits.

———–

Also see in this series: Vladimir Popov, How the Soviet Elite Lost Faith in Socialism in the 1980s, Nov. 19.

———–

[1] Branko Milanovic, “Where in the world are you? Assessing the importance of circumstance and effort in a world of different mean country incomes and (almost) no migration,” The World Bank, WPS4493, January 2008.

[2] Joseph E. Stiglitz, The price of inequality: how today's divided society endangers our future (New York : W.W. Norton & Co., 2012), 9.

[3] Kuznets, S. Economic Growth and Income Inequality. American Economic Review 45 (March 1955), pp. 1–28.

[4] These include: Argentina, Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Mauritius, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Tanzania, UK, and the United States – in all, around half the global population.