Since the 1990s, Russian citizens living abroad have been able to vote in Russian elections for president and parliament as well as in constitutional referendums. With the large-scale exodus of Russians following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the diaspora is becoming a significant voting bloc.[1] Its newest members’ relative youth and dissatisfaction with life chances in Russia raise questions about the level of support for President Vladimir Putin in foreign precincts during this month’s presidential election.

In anticipation of that election, this memo examines the electoral behavior of the Russian diaspora in the previous presidential election, which took place in 2018, with a primary focus on precincts in the West.[2] It illustrates that the voting behavior of the almost 500,000 Russian citizens who cast ballots abroad depended heavily on the country to which they had emigrated, with democratic settings not necessarily undercutting support for Putin. Indeed, whereas support for Putin was much lower in the UK and the Netherlands than among voters in Russia, Russian citizens in a number of European democracies—among them Germany, Greece, and Estonia—were significantly more likely than their fellow citizens in Russia to vote for Putin. Variations can be attributed to the media landscape, the integration of the Russian population into the host country, and the origins of the Russian community in a given country. The identified voting patterns may, if repeated later this month, have implications for the continued use of aggressive soft power tactics in the Baltics and the possibility of annexation of frozen conflict zones.

The Russian Electorate in Western Europe Votes Differently by Country of Residence

For social scientists, the Russian vote abroad represents an intriguing natural experiment in voting behavior that can provide insights into how persons socialized in hybrid or authoritarian environments make political choices in democratic settings. The literature on voting behavior suggests that the environments in which citizens are imbedded as adults, whether at work, in a neighborhood, or in a region of the country, have the potential to reshape the political values they acquired earlier in life, in institutions such as schools and families. Thus, significant exposure to an open society, with its competitive elections and freer media, should produce a Russian electorate in democratic states that differs in its political preferences from voters in Russia itself.

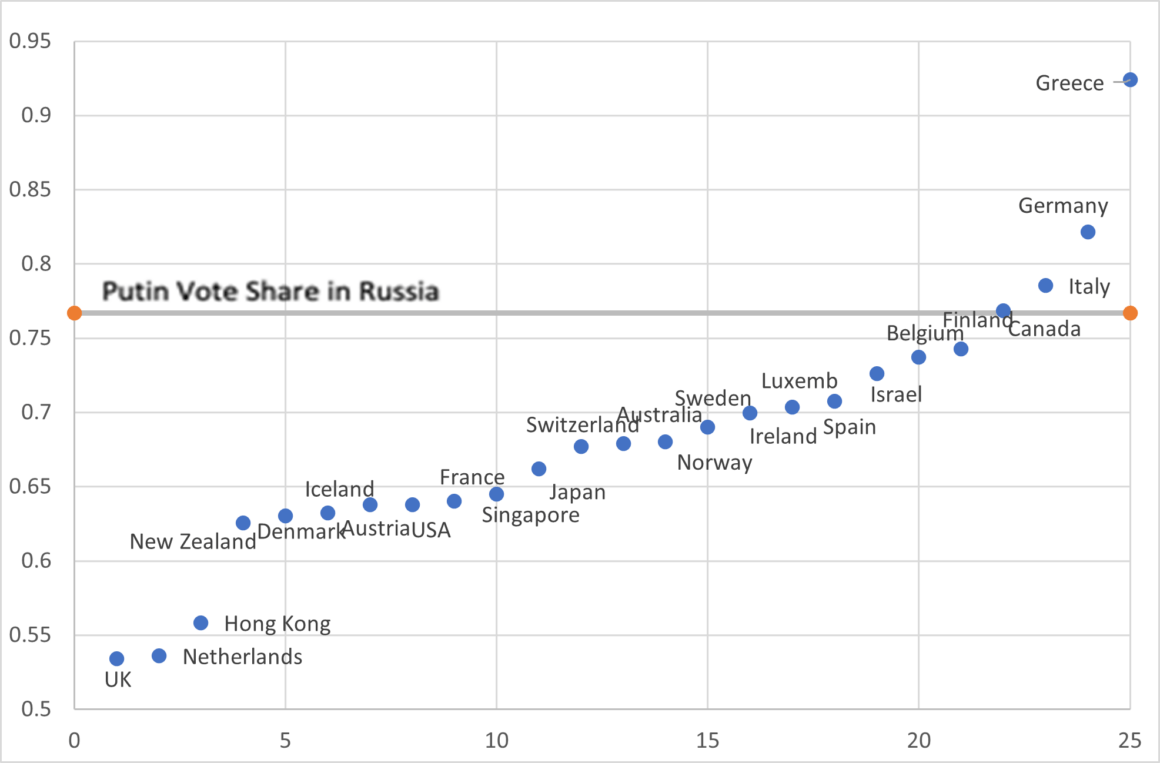

If one takes the Western-based[3] Russian diaspora as a whole, the results from the 2018 Russian presidential election would not appear to confirm this hypothesis. Russian voters casting their votes in democratic states were almost as likely as their fellow citizens in Russia to vote for Putin (74.2 percent vs. 76.7 percent). However, these aggregated results mask dramatic differences in Russian voter preferences by country of residence. Because Russian voters in Germany represented fully one-third of all Russians voting in the West in 2018 (27,503 out of a total of 82,558 votes), the average level of support for Putin by country was well below the 74.2 percent figure noted above (see Figure 1). In other words, all democratic environments are not alike in their impact on voting from abroad in Russian elections.

Results from the 2018 presidential election illustrate the wide disparity between the voting behavior of Russians in the Netherlands and the UK, at one extreme, and those in Germany and Greece, at the other. Whereas in the former countries, only 53 percent of voters cast ballots for Putin, in the latter countries 82 percent and 92 percent of voters did so. Thus, Russian voters in Germany and Greece expressed significantly greater loyalty to the country’s authoritarian leader than did domestic Russian voters.

Another way of assessing the voting behavior of Russians in democratic countries is to tally the number of what might be termed “protest votes,” which in our definition would be ballots cast for the arguably systemic-opposition candidate, Ksenia Sobchak. Predictably, the protest vote is generally inversely related to Putin’s vote share, so we find that although Sobchak received well under 2 percent of the vote among those voting in Russia itself, almost a quarter of Russians casting their ballots in the Netherlands and UK chose Sobchak. At the other extreme, only 7 percent of Russians voting in Germany preferred Sobchak, while in Greece she received a lower share of the vote than in Russia proper (1.56 percent vs. 1.68 percent).

Figure 1. Putin’s Share of the Vote among Russian Citizens Living in the West, 2018 Presidential Election

Explaining the Variations in Russian Voting Behavior in Western Europe

How does one explain these wide variations by country in the voting behavior of Russians living in Western Europe?[4] A serious exploration of that question is not possible in this short memo, but several factors seem to be at work. The first is the overall favorability of the population of the host country toward Russia, which shapes and is shaped by the local media landscape. A 2018 poll by the Pew Research Center found that while 15 percent of the Dutch and 22 percent of the British had a favorable view of Russia, the figures were 35 percent in Germany and 52 percent in Greece. Thus, consumers of traditional media in the Netherlands and the UK would encounter coverage of Russia and its leadership that is more critical than that provided in equivalent outlets in Germany and Greece.

Of particular importance in Germany are vibrant Russian-language media outlets, as well as German-language media, that serve as important conduits for information and disinformation originating in Russia. For example, studies in recent years have revealed the extent to which the Russian state has used German- and Russian-language traditional media, as well as social media, to undermine support among Russian emigres for mainstream German parties and to buttress support for the right-wing Alternative for Germany (AfD), which has close ties to Russia. In Greece, the media reflect the perspectives of a significant portion of the population, which has, for historical and cultural reasons, traditionally exhibited an affinity for Russia. For example, a recent Europe-wide poll showed that whereas only 9 percent of Dutch respondents believed that the Russian invasion of Ukraine was “unacceptable but understandable,” the figure in Greece was 34 percent.

A second factor explaining the divergent results across Europe is the level of integration of the Russian population into the host country. Russian emigres in countries like the Netherlands and the UK appear to be more integrated into the host society than their counterparts in Germany. In fact, one study argued that it was difficult in the early 2000s to speak of a visible Russian community in London and Amsterdam.[5] The level of integration is itself a reflection of a third set of factors, such as the size, density, and origins of the Russian population. Unlike in the UK and the Netherlands, a sizable portion of the Russian population in Germany and Greece are returnees to their ethnic homelands, that is, many are “Russian Germans” or “Russian Greeks.”[6] This background promotes a self-perception of a community apart, which may create stickier identities than individual or family linkages to the homeland alone. Unfortunately, the absence of individual-level data on these and other issues—like length of time in country, frequency of travel to Russia, language knowledge, financial status, and reasons for emigration—make it difficult to reach firm conclusions about the factors that make Russian voters abroad more or less likely to cast ballots for Putin.

Putin Enjoyed Exceptionally Strong Support from Russian Voters in Eastern Europe and Frozen Conflict Zones

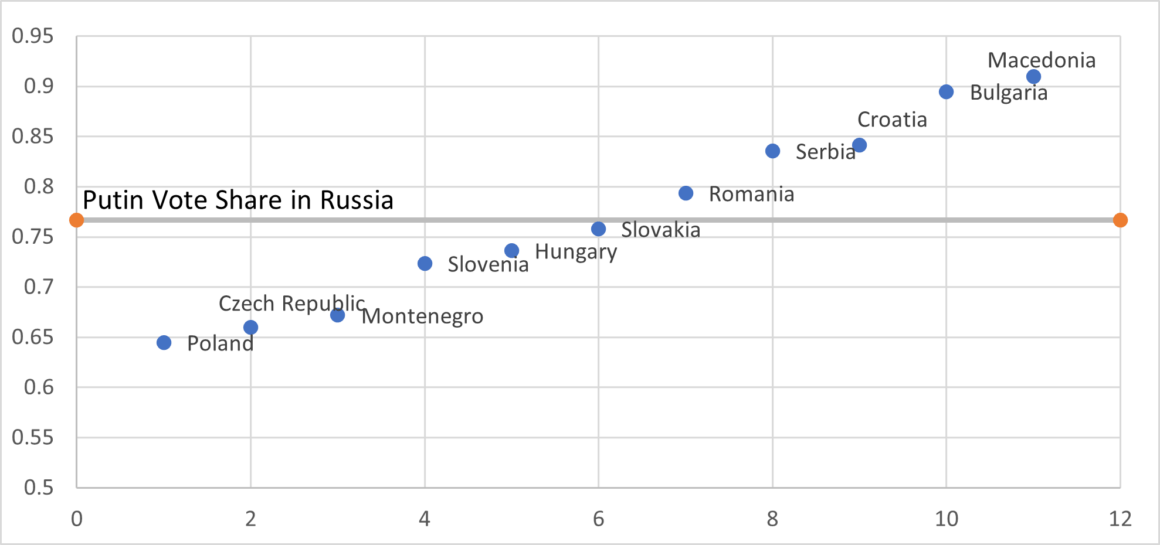

If the results of the 2018 presidential elections in Western Europe may not have alarmed Putin and the Russian leadership about the incipient formation of an opposition voting bloc abroad, the outcome in Eastern Europe may actually have been encouraging for the Russian president and his entourage. As Figure 2 illustrates, levels of support for Putin among Russian voters in a few countries in the region—most notably Poland and the Czech Republic—were somewhat lower than in the domestic electorate. Russian voters in the remainder of Eastern Europe, however, showed little sign of dissatisfaction with the Russian leader, and in several countries, such as Bulgaria and Macedonia, the results approached the levels of support found in presidential elections in the autocracies of Central Asia. Particularly striking was the fact that Russian voters in Croatia supported Putin at a slightly higher level than their neighbors in Serbia.

Figure 2. Putin’s Share of the Vote among Russian Citizens Voting in Eastern Europe, 2018 Presidential Election

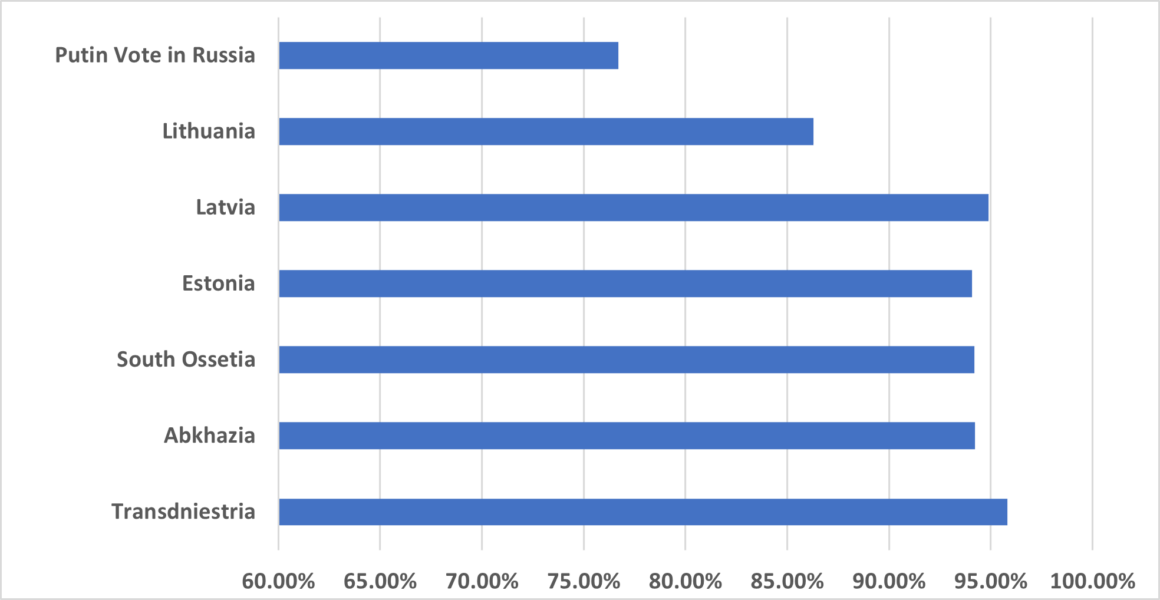

The 2018 results from Russia’s immediate periphery—the Baltic and the frozen conflict zones of Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Transnistria—would have been especially heartening for Putin, and potentially worrying for the West. In all but Lithuania, where the ethnic Russian community is significantly smaller than in its two Baltic neighbors (5 percent of the population vs 25 percent in Estonia and 33 percent in Latvia), Putin received well over 90 percent of the vote (see Figure 3).[7]

It is, of course, impossible to know the effect that the war in Ukraine will have on the voting preferences of Russian citizens in these areas when they cast their ballots later this month, but a repeat of these results could serve as an additional fillip to those in Russia who favor further expansion, whether by hybrid or traditional warfare in the Baltic, or the formal incorporation into Russia of the frozen conflict zones of Transnistria, South Ossetia, and Abkhazia. At a minimum, if this pattern is repeated in the March 2024 presidential election, it would legitimate the continued use in this region of aggressive soft power tactics associated with Russkii mir and related initiatives.

Figure 3. Putin’s Share of the Vote among Russian Citizens in the Baltic and Frozen Conflict Zones, 2018 Presidential Election

Conclusion

We do not yet know how the recent wave of Russian emigres will reshape the country’s diaspora. Two years ago, it was tempting to think that Russian citizens involved in the mass exodus of the early 2020s—many of them young Russian men—represented a group that was turning its back on authoritarianism, literally and figuratively. Yet early indications are that the new emigres are not particularly anti-war or anti-Putin but are instead motivated primarily by the age-old logic of sauve qui peut. To fully understand the attitudes and behavior of this new wave of Russian emigres, we must await in-depth surveys of this group, but the results from foreign precincts in the Russian presidential election of March 15-17 may provide an early indication of whether there has been a change in the attitudes of the expanded Russian electorate abroad toward their long-serving president.[8]

Unfortunately, the Russian government has taken preventative measures to limit voting abroad by reducing the number of electoral precincts by 25 percent (from 393 to 300) and by prohibiting online voting. Moreover, given that voting takes place in Russian consulates and embassies, which are considered the territory of the Russian Federation, emigres who are under indictment or even under suspicion back home will have every incentive to refrain from voting. Although Mikhail Khodorkovsky was willing to vote in Russian embassies in earlier elections, the heightened level of repression that has followed the full-scale invasion of Ukraine may well discourage many Russian citizens abroad who have been openly critical of Putin and the war in Ukraine from participating in the March 2024 presidential election.

Eugene Huskey is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Stetson University. He has published widely on presidencies, bureaucracies, and elections in Eurasia as well as on Soviet and post-Soviet legal affairs.

[1] According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia, in 2018 1.86 million Russian voters lived abroad. An estimated 1 million persons have emigrated from Russia since the beginning of 2022.

[2] The data here are drawn from 393 precincts abroad, whose results were reported on the website of Russia’s Central Election Commission. There is much to learn from a careful study of the precinct-level results from Russian voters abroad across the globe.

[3] I use the term “West” broadly, to include the US, Canada, European democratic states, Australia, and New Zealand, plus Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Israel.

[4] Within-country variations by precinct are not dramatic, though in a few cases they are significant. In Germany, for example, the lowest levels of support for Putin were found in the two Berlin precincts, which registered 73 percent and 76 percent support for Putin, in contrast to cities like Bonn and Hamburg, where over 88 percent voted for Putin.

[5] Helen Kopnina, East to West Migration: Russian Migrants in West Europe, Ashgate, 2005. Subsequent research has pointed to some community-building efforts in Britain, which depend in part on initiatives directed by the Russian state.

[6] Of the estimated 2.5 to 3 million Russian speakers in Germany, over 1.3 million were born or have parents who were born in Russia, and over 500,000 hold dual German and Russian citizenship (presumably this latter group represents the repatriated Russian Germans).

[7] It is important to distinguish between ethnic Russians who are Estonian citizens and Russian citizens who live in Estonia. The literature suggests that the former often have little contact with Russia and have developed a sense of civic loyalty to Estonia. Russian citizens in the country who vote for Putin, on the other hand, could be considered a fifth column. The numbers of citizens of the Russian Federation in Estonia are relatively small but not insignificant in a country of 1.3 million persons. 28,000 Russian citizens in Estonia turned out to vote in the 2018 presidential election.

[8] I say “may provide an early indication” because it is uncertain whether the results will be accessible, as they have been in earlier elections, on the website of the Central Election Commission of the Russian Federation. Since the launch of the full-scale invasion, I have been unable to access the site.