► The September regional elections, held in Russia against the background of discontent caused by pension reform, became a kind of “stress test” for the political system. This test has demonstrated that the political system is relatively stable, yet simultaneously fragile and vulnerable vis-à-vis substantial challenges. This article is a summary of a detailed report on Russia’s regional elections edited by Kirill Rogov and published by the Liberal Mission Foundation in Moscow. Contributors to the report include Alexander Kynev, Nikolay Petrov, Kirill Rogov, Sergey Shpilkin, and Natalia Zubarevich.

This year’s regional election results were somewhat of a sensation. For the first time since 2007, the United Russia (UR) party, the Kremlin’s legislative arm, failed to gain a plurality of the vote in three regional legislatures. UR’s average result declined to 38 percent, down from 46 percent in the previous election. In single-mandate districts, the proportion of UR victories has declined from 92 percent in 2015-16, to 87 percent in 2017, to 72 percent this year. In four regions out of 22, the incumbent heads of the executive branch lost their elections. The “executive vertical” thus suffered defeat in seven out of 38 key campaigns. The population of the territories where elections were held amounts to over 45 percent of the total Russian population, making the September results representative of Russian citizens’ electoral sentiments. The geography of the Kremlin’s electoral failure is skewed toward the Far East, yet—as the examples of the Vladimir and Ulyanovsk Oblasts indicate—these failures are not region-specific.

|

“The administrative machine tightly controlled access to the race, barring unwelcome candidates and party slates from appearing on the ballot.”

|

In the course of the campaign, the administrative machine tightly controlled access to the race, barring unwelcome candidates and party slates from appearing on the ballot. The “systemic opposition”—the Communist Party (KPRF) and Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s Liberal Democrats (LDPR)—was fully amenable to informal deals and “fixed games” with representatives of the executive branch. Those alternative candidates who had solid electoral potential either withdrew from the race or were not nominated by their own parties.

Such tactics were repeatedly used in earlier campaigns. The Kremlin had relied on restricted access to the race, ensuring that the “appointed” leader ran against a hand-selected weak contender. Not only were unwelcome candidates barred from the race, but certain groups of voters also did not come to the polls because they did not find any of the candidates appealing. From there, the mobilization of administrative resources and ballot-box stuffing helped secure the Kremlin’s electoral dominance. In 2018, however, these technologies failed in a number of regions.

Election rigging is an important—and habitual—technology used by the Kremlin. A statistical assessment of “abnormal voting” (which serves as indirect evidence for electoral fraud) demonstrated that on the average, “abnormal votes” in gubernatorial elections amounted to about 25 percent of all votes cast for the incumbent, a figure that rose to 30 percent for party-slate elections. Regional variations, however, are quite significant.

The possibilities and scope of rigging, however, are limited in regions that have advanced electoral cultures, comparatively developed civil society structures, and diversified elites—that is, those in which residents of a large urban center account for a significant proportion of the total population. Besides, as the experience with the September runoffs has shown, large-scale fraud may become practically impossible if, for whatever reason, voters are mobilized and turnout grows rather high.

“Buying votes” by radically increasing budgetary social expenditures and social payments may be effective and contribute to solid victories by regional heads (this was the case in Moscow and Magadan Oblasts, where indirect evidence pointed to low election-rigging). Yet this instrument does not work if there is conflict among local elites or if the incumbent’s initial rating is very low (as was the case in Khakasia).

The failure of the heads of four regions—Khabarovsk and Primorsky Krais in the Far East, Khakasia in Eastern Siberia, and Vladimir Oblast in European Russia—to win re-election in the first round was the main sensation. Before this, a runoff election has happened only once, in Irkutsk Oblast in 2015, since direct gubernatorial elections were reestablished in 2012.

In the highly contested gubernatorial election in Primorsky Krai, UR incumbent Andrey Tarasenko (right) was announced the winner. His Communist rival, Andrey Ishchenko (left), challenged the results claiming that they were rigged. The results were canceled and a new election called for December.

Most concerning for the Kremlin is likely the escalation of protest voting in the four runoffs. The strategy of creating a secure advantage for the favored candidates of the “executive vertical” by picking “technical” rivals failed due to the rise of protest sentiments. After the favored incumbents lost the first round, turnout rose abruptly in the runoff: voters came to the polls determined to cast their ballots against the incumbent. As a result, the “technical” candidates emerged as the winners, with twice as many votes as the defeated incumbents. The failure of the “power vertical” candidates to win in the first round undermined their “overwhelming advantage” and became a mobilizing factor for discontented groups.

|

“After the favored incumbents lost the first round, turnout rose abruptly in the runoff: voters came to the polls determined to cast their ballots against the incumbent.”

|

A major cause of discontent was the pension reform announced in early summer 2018, which caused an abrupt worsening of the social mood and attitudes toward the government. This, of course, cast a shadow over the 2018 campaign. The balance of “right/wrong track” assessments in public opinion surveys dropped to just slightly positive, close to zero. Significantly, this balance was negative in the group of middle-aged, and especially pre-retirement, Russians.

What was unusual in this year’s elections was that the intentionally low turnout and restricted access to the race reinforced the “systemic” opposition parties, the KPRF and LDPR. As the Kremlin artificially restricts the “menu” of political parties, those voters who come to the polls are limited to several conservative constituencies, collectively amounting to 22 percent of registered voters. These constituencies include loyal conservatives, who vote for UR, and opposition conservatives, namely the nuclear electorates of KPRF and LDPR.

In the gubernatorial election in Vladimir Oblast, UR incumbent Svetlana Orlova (left) lost in the runoff to LDPR contender Vladimir Sipyagin (right).

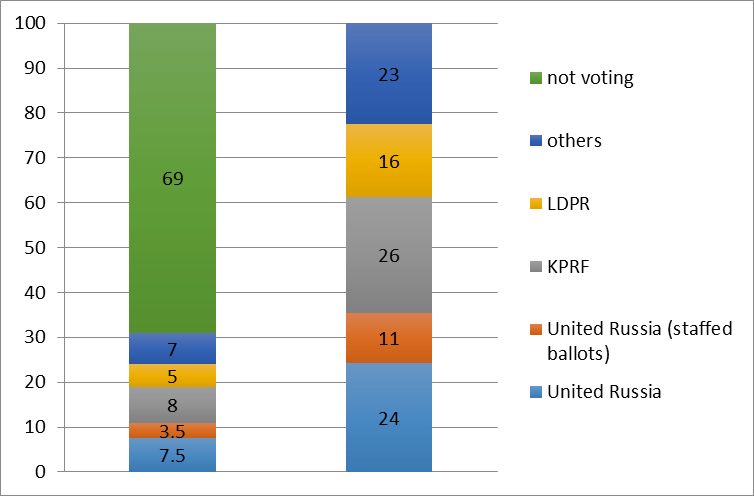

When liberal-minded and centrist voters did not turn out to vote, the weight of the systemic electorate dramatically increased. In September, the average results of regional legislative elections can be estimated as follows: UR gained about eight percent of registered voters and ballot-stuffing for UR amounted to another 3.5 percent of registered voters, for a total of 11 percent for UR. Eight percent voted for KPRF and five percent for LDPR. Pension reform and other factors responsible for a decline in loyalty to the regime led to the defection of a fraction (about 3.5 percent) of loyal conservatives from UR to KPRF or LDPR. Thus, unlike at the turn of the 21st century, in 2018 the LDPR and KPRF emerged as rather strong rivals of UR, capable of defeating it in a number of races.

Figure 1. Average Results in the Regional Legislative Elections of September 2018

Percentage of registered voters (left) and those who came to the polls (right)

Pension reform was not the only factor responsible for the erosion of public support for the authoritarian Kremlin and the escalation of protest in the runoffs. Several factors played a role, first and foremost the continued decline in real wages and people’s real incomes in most of the regions where elections took place. Citizens appeared to have been reconciled to diminished or stagnant incomes after 2014, but in 2018 they were hit hard by a new deduction from their future incomes—which they had formerly deemed secure.

|

“Citizens appeared to have been reconciled to diminished or stagnant incomes after 2014, but in 2018 they were hit hard by a new deduction from their future incomes.”

|

Another factor contributing to the September failures was rising tensions between the Kremlin and the regions, especially the regional elites. After consolidating the regime’s political and electoral positions in 2014-2016 and further empowering its repressive institutions, the Kremlin has pursued a hard authoritarian approach toward regional elites. This has included pointedly arbitrary appointments of acting governors (who then virtually automatically become the “elected” heads of their regions) and repression—or threats of repression—against regional elites, which essentially amounts to “external management” of the regions.

As long as the Kremlin’s electoral positions were strong, this hard policy, despite increasing tensions among elites, did not face direct resistance. Moreover, when the center was popular, this policy was often supported by local constituencies, who regarded it as “purging” their regions of corrupt leaders. But the runoff votes demonstrated that even a relative weakening of general support for the Kremlin may exacerbate the “friend or foe” opposition and lead to collective discontent with the center among both ordinary people and regional elites. The Kremlin may ignore the people if it enjoys the support of regional elites. Equally, it may ignore regional elites if it can draw on solid public support (as was the case in 2015-17). It is hardly possible, however, to ignore both.

Overall, the current situation does not yet amount to a crisis, and the election results do not present a direct threat to the regime. With the September elections behind it, the Kremlin continues to demonstrate relative external status-quo stability. Yet at the same time, regional races revealed the internal fragility of the political system, its vulnerability vis-à-vis an abrupt, unpredicted escalation of protest. This appears to send an alarming signal: the regime may be not as unassailable and rock-solid as it once seemed, while the potential of protest consolidation may have been underestimated.

|

“Regional races revealed the internal fragility of the political system, its vulnerability vis-à-vis an abrupt, unpredicted escalation of protest.”

|

During Vladimir Putin’s two decades in power, there have been two episodes of substantial destabilization characterized by a decline of trust in the regime (and Putin personally) combined with electoral weakening and mass protests. The first took place in late 2004-05 and was provoked by the “benefits for cash” reform and the cancellation of gubernatorial elections. The second unfolded in 2011-12, when Putin’s return to the Kremlin caused discontent among educated urbanites and part of the elite. In the former case, an exceptionally beneficial economic situation enabled the regime to overcome the destabilization; in the latter, the Kremlin resorted to a broad conservative mobilization, hardened authoritarian practices, and an abrupt shift in its foreign policy course.

Just how the Kremlin will respond to the current destabilization episode will become clear in the coming months. One thing may be said with certainty: whatever measures the Kremlin decision-makers opt to take, they will be guided by the overarching goal of adjusting the political system to the “problem of 2024”—when Putin’s fourth presidential term expires.

Kirill Rogov is a Member of the Supervisory Board of the Liberal Mission Foundation (Moscow), Senior Research Fellow at the Gaidar Institute for Economic Policy, and a Member of the Council on Foreign and Defense Policy.

Also see: Putin’s Reelection: Capturing Russia’s Electoral Patterns: A Discussion with Kirill Rogov, June 2018.