Moscow Mayor Sergey Sobianin

► Moscow is Russia’s wealthiest city with the largest concentration of highly-educated and critically-minded Russians. But the Moscow mayoral election is just as non-intriguing as all other regional races to be held in Russia on September 9. Russian experts—Natalia Zubarevich, Alexey Titkov, and Denis Volkov—talk about the Moscow economy, the “urban growth machine” built by Mayor Sergey Sobianin, and the perceptions of Muscovites.

The second Sunday in September is Russia’s common election day. This year it falls on September 9. A number of regions will elect their local legislatures and about two dozen regions will hold gubernatorial elections. One of them is Moscow, where residents will have an opportunity to cast their ballots in the mayoral election.

Common to all these races is the virtual absence of contestation. The result is preordained: the pro-Kremlin United Russia party, which has a solid majority in the assemblies of all 80-plus Russian regions, is sure to reassert its dominance in those regions where elections will be held on Sunday. In the case of gubernatorial elections, victory is sure to go to candidates of the Kremlin’s choosing, usually the incumbent (or acting) governor.

Moscow is no exception. Although it is Russia’s wealthiest city, with the highest concentration of highly educated, well-informed, and critically-minded Russians, the mayoral election is almost entirely devoid of any intrigue: incumbent Mayor Sergey Sobianin is sure to win in a landslide. Some of those who had sought nomination were barred from running at earlier stages, apparently deemed unwelcome by the Kremlin. The ballot will contain four names in addition to Sobianin’s, but none of these candidates is serious competition for the incumbent mayor.

Muscovites are no more concerned about the virtual lack of electoral choice than their compatriots in other Russian regions. It is broadly assumed that this is the way the Kremlin has designed it and trying to change it is pointless. The obvious cost for the Kremlin is that a relatively low number of people will bother to go and vote: what is the point of voting if the result is already known? But the government does not mind low turnout.

The only element of this election causing intrigue is pension reform, namely the raising of the retirement age, announced by the government in June. The reform prompted almost unanimous discontent among Russians; numerous, albeit not too large or radical, street protests were staged across the country, including in Moscow. United Russia’s favorability rating declined, as did Putin’s approval rating, which had been hovering at or above 80 percent ever since the incorporation of Crimea into the Russian Federation.

About ten days before the common election day, Putin addressed nation on television, promising a number of measures to soften the blow. Appropriate revisions are almost sure to be made in the final version of the pension reform law. According to a poll by the WCIOM agency, the president’s address has served to reduce the population’s willingness to participate in protests. But even before Putin’s address, the same agency had predicted, on the basis of its August poll, that Sobianin would gain about 70 percent of the vote in the Moscow mayoral contest.

Below, Natalia Zubarevich, Russia’s leading expert on the economies of the Russian regions, writes about Moscow’s economic advantages and the way Mayor Sobianin’s team manages Russia’s largest urban agglomeration. Alexey Titkov of the Higher School of Economics talks about how Sobianin’s policies differ from those of his predecessor, Yuri Luzhkov, and describes the “urban growth machine” Sobianin has built. Denis Volkov, of the Levada Center polling agency, shares his observations about Muscovites’ public opinion.

Moscow City Hall

What has Moscow Mayor Sobianin’s Team Achieved?

Natalia Zubarevich, Director of Regional Programs, Independent Institute of Social Policy

Three key factors define Moscow’s economic development. The first is the huge competitive advantage the capital enjoys as the largest urban agglomeration in Russia. The second is Russia’s highly centralized government, which draws financial, human, and other resources to the capital. These two factors remain the same regardless of who holds the office of Moscow Mayor. And finally, there is the third factor: the quality of city management. Sobianin’s team announced the following priorities: developing Moscow’s transport infrastructure, bogged down in traffic jams; reasserting control over the construction industry and developers to put an end to infill construction; and increasing the tax revenues controlled by the city. Another—unstated—priority was to cut the cost of social commitments and related budgetary expenditures, which had been inflated under former mayor Yuri Luzhkov.

These priorities have been achieved, and sometimes even overachieved. Control over the construction industry was established soon after Sobianin became mayor, through the process of reviewing hundreds of construction permits. In 2017, the Moscow government announced a costly “renovation” program. [Editor’s note: “Renovation” envisaged the demolition of several thousand five-story apartment buildings, known as Khrushchevki after Nikita Khrushchev, who introduced the mass construction of these housing units. The residents of Khrushchevki were told that they would be relocated to what the authorities said would be better housing. See the image below/right of the public protests.] the main goal of which was to keep the increased budget revenues in Moscow and prevent them from being appropriated by the federal government. The renovation will be conducted, for the most part, by the construction department of the city government and funded from the city budget; this will dramatically strengthen the role of the city government in the Moscow construction market and contribute significantly to its virtual nationalization.

Moscow is the richest of Russia’s 85 regions, but the credit for this should not go to the Moscow mayor’s office. Thanks to its status as the Russian capital and the advantages of the Moscow urban agglomeration, the revenues and expenditures of the Moscow budget amounted to 20 percent of the total expenditures and revenues of the Russian regions in 2017. This enables the Moscow government to invest massive funds in the development of the capital’s transport infrastructure. But it is still Sobianin’s team that has concentrated budgetary funds for the achievement of these particular goals: Moscow spending on its transport systems amounts to two-thirds of the budgetary funds that the Russian regions as a whole allocate to transport.

The concentration of population and business in the Russian capital adds to its investment attractiveness. Moscow accounts for over 12 percent of total investments made in Russia; this is about the same as the collective investment raised in the two major oil-producing regions (Khanty-Mansi and Yamal-Nenets autonomous areas of the Tyumen region). But in Moscow it is the city budget that has become the driver of development: budgetary investments account for about one-quarter of total investment in Moscow. This helped Moscow to get over the economic crisis of 2014-2016 without suffering a decline in investment (in Russia as a whole, investment dropped by 12 percent during the period between 2013 and 2016). In 2017, Moscow had 13-percent investment growth.

In addition to the development of transport infrastructure, the Moscow government has conducted a large-scale beautification program. The results are highly impressive, but the costs are still an issue. In 2017 and the first half of 2018, Moscow expenditures on beautification amounted to 11 percent of its enormous budget. This is comparable to total expenditure on Moscow schools and kindergartens—or the budget of Tatarstan.

The Moscow government managed to significantly increase budget revenues from property and small business taxes; this was achieved by conducting a cadastral appraisal and a revision of the system of small business benefits. However, it is only in the past two years that property tax revenues have grown faster in Moscow than in Russia as a whole. In 2015-2018, Moscow has boasted a more-than-20-percent annual increase in tax revenues on aggregate income (tax paid by small businesses). The city government managers can certainly take credit for that, yet in a gigantic and wealthy city such as Moscow, businesses have good development potential and can easily pay more taxes.

It should be pointed out that property and small business taxes account for relatively small shares of Moscow budget revenues (8 percent and 4 percent, respectively). The largest sources of tax revenues are personal income tax (40 percent in 2017) and profit tax (36 percent). The question then arises: if the Moscow budget is so heavily dependent on income taxes, why are Muscovites’ opinions not taken into account when decisions about city development are made?

The Moscow budget’s social spending was rather harshly cut: although revenue was growing, in 2014-16 education and health expenditures did not rise or even decreased. Educational institutions were enlarged (by forced mergers) and the number of hospitals was reduced. Social welfare expenditures grew a little faster, but even so the special supplements to Moscow pensions were reduced. The pension supplement had been introduced by the previous mayor of Moscow, Yuri Luzhkov, yet under Luzhkov it was calculated based on the minimum subsistence level [which was raised annually in order to compensate for inflation], whereas under Sobianin it was capped in ruble terms. This enabled the Moscow government to cut the cost of the supplementary pensions: under Luzhkov Moscow retirees were assured of 10-percent supplements to their government pension, and in 2016, under Sobianin, those supplements were reduced to 6 percent.

In 2017, as the presidential and mayoral elections approached, the Moscow government changed its policy and increased social spending. The dynamic of the first half of 2018 is especially revealing: the social expenses of the Moscow budget went up by 16 percent. Of these, social payments to the population rose by more than 25 percent; healthcare expenses, including the territorial fund of сompulsory health insurance, went up by 15 percent; education allocations increased by 13 percent; and allocations for culture and cinematography grew by 34 percent. The growth rate of social expenses in Moscow is significantly higher than the Russian regional average, with healthcare expenses the only exception.

To sum up: the policy of the Moscow government is to develop the city, its infrastructure, and its urban environment. Unlike other regions, it has the funds to do so. Other priorities—improvement of tax collection and the quality of management—are also being realized, though some problems remain. As for various social programs and the needs of Muscovites, the city government usually remembers them only at election time. And then it spares no expense, since additional spending on “the electorate” is not much of a burden on the capital’s enormous budget.

Tverskaya Street, Moscow

Public Opinion in Moscow

Denis Volkov, Head of Applied Sociological Research Department, LEVADA Center

Maria Lipman: How are Muscovites different from the rest of the Russian population and what perceptions do they share with their compatriots?

Denis Volkov: In Moscow, people are better informed, they show more interest in news; the percentage of those who draw on multiple news sources is higher in Moscow than elsewhere in Russia. But this does not mean that Muscovites’ political attitudes are different from those of Russians at large. A majority of Muscovites approve of President Putin’s policies. Those who do not are not too numerous compared to the total population of the capital. Not infrequently, however, they get vocal about their disapproval. Besides, in Moscow they have less fear, and in recent years they have gained the experience of organizing protest rallies.

On the whole, however, the mood is more tranquil—or quiescent—in Moscow than in the country at large. Muscovites have fewer grievances than Russians who live in other regions. They realize their privileged situation and appreciate their special status; in focus groups, we hear them say that this is the way it should be.

Lipman: What do Muscovites think of Mayor Sobianin and his initiatives?

Volkov: Sobianin was not popular to begin with, but public perceptions of him gradually improved (only about 30 percent had a positive view of him at the time of his appointment in 2010; that number reached 50 percent this year. The number of those who think negatively of Sobianin has declined from 15 to 9 percent). A majority of Muscovites tend to have a neutral or positive attitude toward Sobianin, but this positive perception does not imply admiration.

There is a special category of Muscovites who dislike him: those who refer to themselves as korennye moskvichi [Editor’s note: “Native Muscovites”—those who were born in Moscow or can boast several generations of Muscovite ancestors] and resent the ongoing massive renovation/beautification initiated by Sobianin. People in this group commonly say, “This is not my Moscow. The environment has changed too much.”

In focus groups, we generally see a positive trend when people talk about concrete issues: they commonly admit some improvements, though of course not on every issue; some problems have just grown less pressing.

One example is public transportation: our respondents say that Moscow public transport has improved, but they still complain about traffic jams. Mayor Sobianin’s concrete initiatives are seen rather positively, even those that provoked street protests by smaller groups, such as the construction of new churches in public parks or the demolition of retail kiosks (about one-third of the Moscow population disapproved of the demolition, but the majority thought it was a good idea). [Editor’s note: In 2016 the Moscow authorities demolished dozens of kiosks selling basic food, flowers, etc. The goal, according to Moscow officials, was to bring order to city planning and get rid of the kiosks, which were deemed unappealing or unhygienic. But the demolition was conducted with complete disregard for the property rights of the kiosk owners, many of whom had perfectly valid permits and, as a result of the demolition, lost significant investments they had previously made.]

Public rallies staged in recent years may have mobilized groups of Muscovites around various causes, but of course, percentagewise these groups were tiny. Even more importantly, unlike the protests of 2011-12, which brought together about 100,000 people (also a tiny minority percentagewise), and enjoyed broad support among non-participants, these days Muscovites at large show much less sympathy for street protesters.

Also, unlike the 2011-12 protests, which had political leaders—or at least prominent political figures—the participants in recent protest rallies do not welcome political activists. They hope that the authorities will redress their grievances, and their goal is therefore to “make an agreement with the government.” And indeed, sometimes the authorities make certain concessions. [Editor’s note: This is arguably the way people perceived the softening of pension reform by Putin in late August, less than two weeks before election day.]

Another cause of protests was Sobianin’s “renovation” initiative, which saw passionate protests staged by those who saw this initiative as a forced resettlement that encroached on people’s rights. Subsequently, however, passions subsided, and the actual residents of the 5-story high buildings were the least likely to express outrage. In fact, they were all for the relocation, as soon as they realized that they would not be resettled by force to some god-forsaken place.

The introduction of paid parking remains a problem. Despite official statements that paid parking zones have been expanded in order to alleviate traffic problems, Muscovites refuse to see it this way. Instead, they believe that the government simply “wants our money.”

The problems that have not been solved and remain the most common causes of Muscovites’ complaints include traffic jams and access to high-quality health care; the latter is further aggravated by the prospect of later retirement. People commonly complain that they may not live long enough to reach the (raised) retirement age, and even if they do, they will be in poor physical condition and badly in need of medical care that will remain too costly and/or inaccessible.

The perception of labor migrants has softened somewhat. 2013, the year of the previous mayoral race, was the peak of migrantophobia. Aleksey Navalny, who ran against Sobianin in that campaign, made migrants his main theme. The problem of migrants figured fairly large in that campaign as a whole, further aggravating Muscovites’ negative perceptions of “people from the Caucasus” and labor migrants from Central Asia.

Navalny subsequently toned down this rhetoric and has since stopped talking about it altogether.

At the official level, discussion of migrants has also been mostly avoided. The government realizes that Russia cannot do without migrants and tries not to raise this issue. This may be one reason why the problem no longer looks as grave as it used to. Another reason may be the economic crisis followed by a recession. The economic decline means there is lower demand for migrant labor. In focus groups, people do not sound friendly toward migrant workers, but they admit that “migrants have become fewer.”

The deepening confrontation with the US may also have had an effect: the sharp rise of negative sentiments toward America has superseded, as it were, negative feelings toward labor migrants, pushing the migrant problem to the background.

Natalia Zubarevich mentioned recently that the number of migrants has been growing again, but our surveys have shown that people are no longer as furious as before; they may simply have become used to seeing labor migrants around. In 2017 our data showed that migrantophobia had dropped to its lowest level since 2009; according to a very recent Levada poll, however, in 2018 negative sentiments toward labor migrants have begun to rise again.

Moscow fared better than most other Russian regions during the economic decline of 2014-15. The city’s sheer size helped Muscovites adjust to lower living standards. Beginning in mid-2016 and throughout 2017, perceptions of the economy improved overall, and particularly in Moscow. Putin’s election to a fourth term in spring 2018 boosted people’s morale and produced a surge of optimism. But this optimism has begun to fade away, especially since the announcement that the retirement age would be raised.

Lipman: What is your sense of this September 2018 Mayoral Election?

Volkov: The most important factor in this election is the virtual absence of challengers to the incumbent mayor, Sergey Sobianin. This means that whatever discontent exists, there is nobody to take advantage of people’s negative sentiments. Opposition figures were barred from running some time ago, and have generally been silent of late.

To those critically-minded Muscovites who have a negative perception of Putin, Sobianin is part of Putin’s political establishment, and they have a negative attitude toward Sobianin as well. Sobianin keeps a relatively low profile and this probably helps him maintain a reasonably positive image. Compared to his predecessor Yuri Luzhkov, who was highly visible, Sobianin who does not have Luzhkov’s charisma, keeps a relatively low profile, and this probably helps him maintain a reasonably positive image.

In our survey of April-May 2018, about 30 percent of Muscovites were willing to vote for Sobianin in the September mayoral election; other candidates (including those who were later barred from running) gained about 1 percent each, with Navalny no exception. Muscovites say they want a candidate who “will solve their problems” or “has something to offer”—apparently they do not see Navalny this way.

The lack of competition is generally not seen as a problem. The general attitude is not enthusiastic but quiescent: “I suppose I ought to do it” was a common answer to the question of whether respondents were going to go and vote. The overall number of those willing to come to the polls is not too large, but unlike in 2011-2012, when angry sentiments gave rise to mass protests, today there is no strong antagonism toward voting for the incumbent; the general mood is that of acquiescence.

The announced raising of the retirement age will likely affect turnout, however. There is a desire to show the authorities: they took away our early pensions, so we will get them where we can and ignore the election. Yet since there is no alternative to Sobianin, this will not have a substantial effect on the election result. The authorities need the loyal to turn out, and they don’t care too much about the rest.

A few weeks before the election, Sobianin, apparently seeking to placate Muscovites, announced that as of August 1, pensioners in Moscow and the Moscow region will be assured of free use of commuter trains. This initiative has been well noticed and is much appreciated.

September 9 Voting Information (For One of About 3,500 Moscow Precincts)

Russian Authorities: Always Hedging Against Unexpected Developments

Alexey Titkov, Associate Professor, School of Political Science, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow

Lipman: Moscow Mayor Sergey Sobianin is sure to win, yet all his “non-systemic” or reasonably autonomous opponents were still barred from running. Why is there not even an appearance of contestation at this year’s mayoral election?

Titkov: Moscow is a large agglomeration. The way the campaign is managed and “the filters” are used here depends on the Kremlin, not on the city authorities. (Introduced back in 2012, “filters” require that prospective candidates collect the endorsement signatures of a certain number of lower-level municipal deputies in order to be nominated; such “filters” are designed to bar unwanted candidates.)

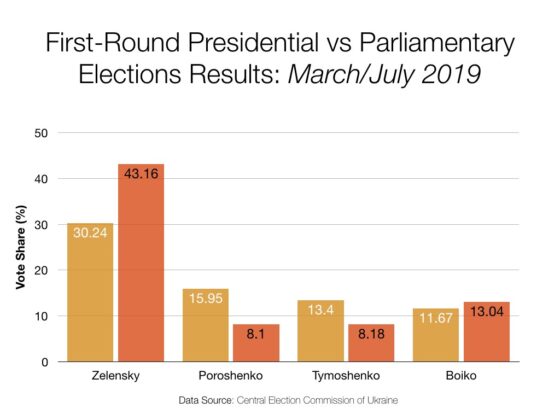

The election is uncontested. This is the scenario that is currently playing out in about two dozen gubernatorial races all across Russia. In the 2013 regional elections, the scenario was different. The Kremlin was experimenting with granting access to the electoral campaign to non-systemic candidates. This was the case in a few regions, including Moscow. In other regions, this scenario had successful outcomes for the Kremlin, but in the Moscow mayoral election Aleksey Navalny gained 27 percent of the vote. This was unexpected—an obvious failure for the Kremlin decision-makers—and they took the experience of 2013 into account.

For this year’s elections, the Kremlin opted for non-competitive campaigns. This decision has to do, in part, with the relatively large number of young and inexperienced technocrats in gubernatorial offices. The Kremlin strategists decided to provide a “sheltered” regime for them. For the Moscow mayoral election this year, the Kremlin’s main priority is to lower the risk and avoid any hazardous developments.

Regardless of the character and mood of the Moscow voters and however reliable the election designs may seem, the actual vote might produce an unexpected result. Remember the latest municipal elections. It seemed that the Kremlin organizers had picked an ideal time: with the election scheduled for September, the campaign was inevitably shortened, since in July-August many Muscovites leave on vacation. However, this also created the risk that fewer of Moscow’s loyal voters would be mobilized (since they would be more likely to be at their dachas) than the regime’s opponents (younger, urban voters more likely to be having fun in the city). The Moscow electoral districts had been carefully rearranged in a way that benefitted the pro-mayor vote—and yet in critically important districts the opposition candidates performed well. That experience showed that granting access to non-systemic candidates is always risky. The authorities always need to hedge against unexpected developments.

Lipman: Sobianin has a decent approval rating. Unlike Putin, whose broad public support is largely symbolic—as the embodiment of the Russian state, rather than as a well-performing chief executive—Sobianin appears to have earned his approval rating by being an effective city manager. How would you describe his performance?

Titkov: If we put aside the authoritarian political environment, Sobianin is a standard, recognizable type of a successful politician in an urban constituency. A mayor like that can be found in London or New York City. Sobianin’s Moscow has a functioning “urban growth machine” that consists of the city administration, big business, developers, etc., who support each other; their interests are compatible and their operation is generally beneficial for city residents.

One example of how the urban growth machine works is the construction of the Moscow Сentral Circle line—a newly-built train line connecting former industrial zones. This is a project that is attractive to developers, while for residents the new line is a convenient addition to the city transport infrastructure.

The distribution of winners and losers from Sobianin’s government’s policies is not unfamiliar to Western/American urban “growth machines.” In 2015, Sobianin’s government launched a mass demolition of retail kiosks, mostly located near metro stations and selling basic food and a variety of small items. This initiative outraged the small traders and kiosk owners. Sobianin’s 2017 “renovation” program, aimed at tearing down 5-story-high apartment buildings and relocating their residents, produced a large—though still small on the scale of the city, which has about 12 million residents—well-organized and radical group of discontented Muscovites who protested against this program.

But public discontent was a cost the government was prepared to accept: the renovation program had obvious benefits for the developers and those dwellers who believed that they would be relocated to higher-quality apartments. [Editor’s note: the program has not yet been implemented and we do not know whether their expectations will be met.] And these benefits apparently outweighed the discontent. Thus, on the one hand, by offering incentives and rewards to developers, trading organizations, etc., Sobianin has built an efficient “urban growth machine,” but on the other, his policies have also generated risks by alienating certain groups.

A large megalopolis, such as Moscow, a city of federal scope, always has well-organized groups capable of staging protests, and the government regards them as a risk. It may not be a serious problem if an opposition candidate gains 10 or 15 percent of the vote in the mayoral election (this is how much the communist candidate and the one nominated by “A Just Russia” may gain between them on September 9), but 100,000 people in the streets can seriously interfere with the political agenda, even if the actual number of people is smaller. This is exactly what happened back in 2012 after 100,000 people joined the protest rally in Moscow.

Lipman: What are the similarities and differences between Sobianin and his predecessor, Yuri Luzhkov?

Titkov: Luzhkov’s “power base” consisted of pensioners and public sector workers: teachers and doctors. [Editor’s note: The introduction of the market economy has not changed the position of medical professionals—the majority remain on the government (state or regional) payroll.] They were grateful to Luzhkov because their needs and interests were taken care of, and they were assured of better services than those “beyond the Moscow beltway.”

Sobianin draws on other constituencies, and doctors and teachers feel disadvantaged in comparison to the Luzhkov period. Their discontent is mostly quiet, however. [Editor’s note: Regarding Sobianin, compare with Natalia Zubarevich’s “cutting the costs of social commitments… that had been inflated under former mayor Yuri Luzhkov.”]

What makes the two mayors similar is the way they use media to their benefit. When Luzhkov was Moscow mayor, free district papers extolling his performance were stuffed in people’s mailboxes, even outside campaign season. Sobianin, too, relies on solid media support.

Sobianin encourages investment in projects that are highly visible, such as the reconstruction of the city center and the beautification of city parks, so that people will see that he works for them. That being said, Sobianin’s construction and beautification projects endanger historical monuments and buildings, and this often creates discontent among those in Moscow who are concerned about historical landmarks, etc. This constituency, however, accounts for a small minority.

The Kremlin’s policy toward Мoscow holds that the Russian capital city must live better—at least, living standards should not decline, regardless of what the situation is like elsewhere in Russia. Moscow should remain the magnet for anyone with high ambitions. This policy is driven by the idea that Russia needs to have a city of global scope, and emphasis is placed on developing Moscow without any restrictions. Since the 2000s, Kremlin policy has also implied that Moscow should be compared—or “compete”—not with other Russian urban centers, but with the largest global cities. For now, Moscow lags behind Shanghai, London, or Amsterdam as an economic, financial, or urban planning center.

Lipman: What are your thoughts about the Moscow election and pension reform?

Titkov: The announced pension reform comes at a cost and has raised the risk of people taking to the streets. On September 2, the communists, together with a “left coalition,” staged “People against the pension reform” rallies [see image below/right] around Russia, including Moscow, but their protests failed to attract many people and were in fact even smaller than similar rallies staged in July, at the start of the street protests against raising the retirement age.

Aleksey Navalny called for a rally right on election day, September 9, but the city authorities refused to issue a permit for his rally, and Navalny was sentenced in late August to a 30-day prison term. Last year, Navalny’s non-sanctioned rallies brought together a maximum of 5,000 or 10,000 people. Those street actions were focused around anti-corruption or the demand, in the run-up to the presidential election, for free elections and a transfer of government power. This time, there are likely to be fewer participants. For the radical youth, who constitute Navalny’s main supporters, pensions are not such a burning issue, while disappointed adults are generally more moderate and unwilling to take the risk of joining an unsanctioned rally.

The campaign has not been especially intense, to say the least, mostly reduced to ads calling for people to come to the polls; it will hardly become more intrusive during the final few days before the election.

For the Moscow government, as well as the federal authorities, 30-percent turnout or a little more will likely be sufficient. Even in the 2013 mayoral election, which was competitive, the turnout was not too high. The authorities can always explain that people were not anxious to come to the polls, either because they are generally contented or because it was a sunny day and many left for their dachas.

If turnout is less than 20 percent, then this may be seen as a crisis of legitimacy, but the likelihood of such low turnout is small.

In other Russian regions, local administrators are sometimes engaged in a kind of competition: which governors will be able to provide high turnout The expectation is that those administrators who provide comparatively high turnout will be rewarded, while those whose regions demonstrate relatively low turnout will be punished. As a result, the head of the region becomes nervous and urges his regional electoral commission to deliver a higher result; not infrequently, election officials lack the needed skills and opt for primitive rigging, which may lead to a public scandal. But I have never heard about this kind of “competition” among Moscow districts. In Moscow, attempts to raise turnout are risky: they may deepen voters’ exasperation. That is why district heads do not push local election officials to ensure higher turnout. [Editor’s note: However, during the last days of the campaign the city authorities apparently grew concerned about the turnout level and intensified their effort to encourage people to come to the polls. Muscovites were bombarded by text messages reminding them about the election day sent by the city electoral commission and even through online banking apps. Additional precincts were opened in the countryside, so those spending the weekend at their dachas would still be able to cast their votes.]

Pension reform is thus the only factor in this election that can qualify as intriguing. Both the Communists and members of “A Just Russia” have been quite active in trying to take maximum advantage of public discontent over pension reform.

There is a risk of repeating the 2011-12 Duma campaign: at that time, United Russia was losing support, while the Communists and “A Just Russia” were gaining votes. This time around, the Communist candidate and the candidate nominated by “A Just Russia” might gain more than 10 percent—this will be good for both parties because they will preserve their relative prominence, but will be of basically no harm to Sobianin.