► Thanks to the rapid development of mobile Internet, practically every young Russian is an Internet user, regardless of whether he or she lives in a large urban center or in the provinces. The “digital gap” between the youth and other generations is quite significant, but this hardly means that young Russians are a substantively different constituency in terms of their political views or civic engagement, says Levada Center Sociologist Denis Volkov in an interview with Maria Lipman.

Maria Lipman: What is your take on the “grassroots modernization” that has become a trendy issue among experts and scholars in Moscow?

Denis Volkov: I prefer to talk about the rise of civic activism. My sense is that although such a rise is hard to deny, these changes are qualitative rather than quantitative. Such a dynamic in public opinion is very hard to trace. The compatible polling data that can be found indicates that the number of Russians who take part in civic activities may be growing, but if so, only insignificantly. On the other hand, looking at the amount of donated money, we see significant growth in individual donations. People are donating more. In all likelihood, this is due to the changed character of charitable donations: people used to donate clothes and other items, but it may have become easier for them to donate money.

In addition, charitable organizations and funds have become more professional—I mean funds such as Nuzhna pomoshch (Help Needed) or Podari Zhizn (Give Life); there are, of course, others. These organizations have learned how to raise funds, set goals, and organize campaigns, and this has enabled them to achieve improvements in whole sectors, such as hospices that largely rely on charitable donations. Charitable organizations have managed to attract as donors not only individuals but also businesses.

Lipman: You’re talking about donations and charitable work. Do you see changes in civic activism of other kinds—even if that change is qualitative, not quantitative?

Volkov: Other kinds are very hard to measure: when we ask people about these matters and discuss them in focus groups, we see that people are generally unwilling to talk about it. I wouldn’t say they do not understand what we are asking, but they simply do not regard their activity as civic or charitable, much less as actions that might help to change the situation in the country. It is hard to get them to talk: they often tell you that they do not take part in anything of this kind, but after you have talked to them for a while, such activism comes up. It is not that they believe it’s inappropriate to talk about it, it is just not done. And people certainly do not regard what they do as a way to achieve serious change—rather, they see it as personal: if they do some kind of charitable work, they do it for themselves “because I like to do it,” and that is seen as the right attitude.

|

“People certainly do not regard what they do as a way to achieve serious change—rather, they see it as personal.”

|

Lipman: Why do you think people are unwilling to talk about their donations?

Volkov: I believe it is because this kind of activity is relatively new. For the 70 years that the Soviet Union existed, it was impossible to do charitable work. Any attempt to organize, no matter how small-scale, was considered suspicious and even dangerous. In the late Soviet Union, it was no longer so scary, but it was certainly not encouraged by the state.

Before the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, there had been serious improvements; charitable work and civic activism were on the rise. But then this was terminated. These days, such activity is in an early stage: it has only been 20 or 30 years since the collapse of the Soviet system and that is not long enough. Nor does today’s government encourage such efforts. After the Law on Foreign Agents was adopted, Russian funds and the charitable community were terrified, so now they tend to keep a low profile and constrain themselves. Only a very few organizations are willing to articulate that their goal is to achieve serious change. Meanwhile, there is a strong sense in society that “whatever you do, you’ll never achieve serious change.” So, on the one hand, this kind of activism is new, and on the other, civic activism—and especially what is referred to as “advocacy” (there is no such word in Russian)—is aimed at impacting government decision-making. According to the Foreign Agents Law, such effort qualifies as “political activity,” and engagement in “political activity” is highly unwelcome. Therefore, supporting a civic initiative is a bit scary. You never know whether an organization that you have supported with your donations may be labeled a “foreign agent” and whether you might be punished somehow for supporting something inappropriate.

|

“There is a strong sense in society that “whatever you do, you’ll never achieve serious change.“

|

Lipman: Are the qualitative changes you mentioned more common among young people?

Volkov: Based on polling alone, I cannot draw a definitive conclusion that this is a phenomenon characteristic of young people. It depends on the kind of activism. If we are talking about taking part in an organization’s activities, by supporting them or volunteering, then the young are more active, especially young residents of large urban centers—they indeed stand out. But when it comes to donating, middle-aged Russians donate more often simply because they have the money; if we’re talking about the parish or religious community work, women of a certain age are the most common category. Parents’ associations, of course, consist of those who have children. Overall, the young are not much more active than others. If we look at activism more broadly than socio-political activism and include neighborhood sports teams, choirs, and sports organizations, then the young will be more noticeable.

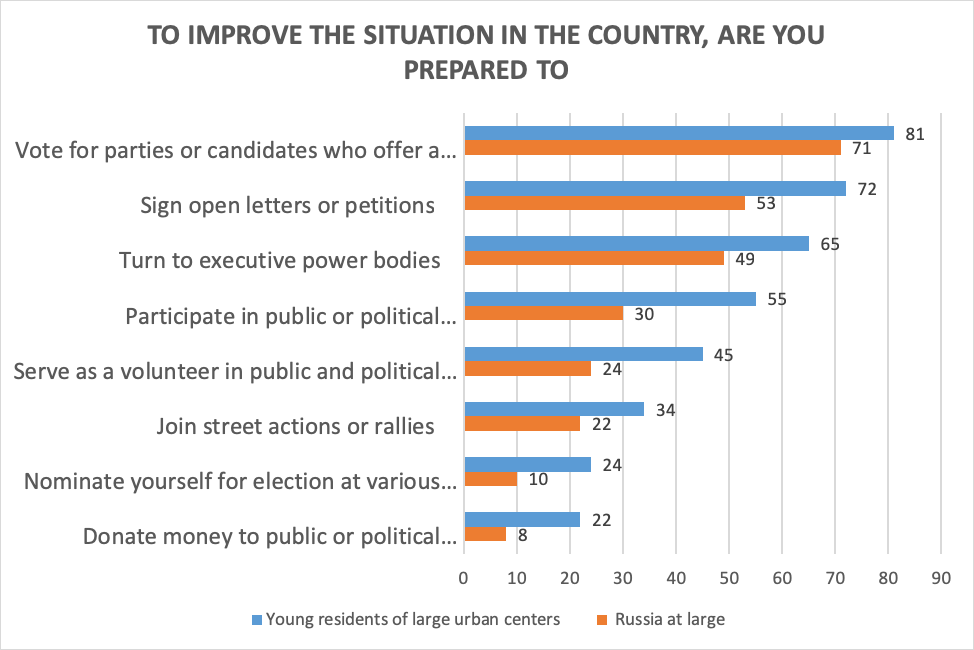

Figure 1

December 2018, young Russians (telephone and Internet poll) – September 2018

Lipman: Your figure 1 shows comparative data on civic activism among urban youth and the Russian population at large. Your question includes the phrase “to improve the situation in the country”—and yet you say that people do not regard their activism as a means to improve the situation in the country?

Volkov: This wording was our client’s choice. And after conducting that survey we decided to compare the results with the data on the country at large. It should be noted, however, that in the survey of youth we drew on telephone and online polls, and that might explain why the results are so high. We were experimenting and realized that in a telephone poll, questions on civic activism produce higher results. Yet the data on the population at large used in this comparison was based on our traditional method of door-to-door polling.

Lipman: Indeed, in some questions the difference between urban youth and the population at large amounts to 20 or 25 points… You have also conducted surveys of youth that included a broader range of questions. What is your definition of “youth” and how large is this age group?

|

“Youth are not of primary importance to the government because they are relatively few, have fewer connections, and more often than not do not vote.”

|

Volkov: In our surveys, the 18-25 age group is the youngest. It is a small group, under 10 percent of the population. Therefore, while the thinking and behavior of this group is, of course, interesting and important, it is not very significant on the national scale. In its policies, the government mostly has in mind those of retirement age—a loyal and much more numerous group than the youth. Based on many parameters, a somewhat younger age group is similar to the pensioners. Youth are not of primary importance to the government because they are relatively few, have fewer connections, and more often than not do not vote. Therefore, the government may “forget” about them for a while. During the mass protests of 2011-12, it was not just about protesting—people felt optimistic, eager to do something. In theory, that was a moment when the government could have joined forces with the younger generation and achieved something for the country. But the government chose instead to suppress that drive.

Lipman: Still, youth appear to attract much attention from experts and media—in Russia and abroad—who associate certain hopes with them. What is your sense of the mood of this group, even if it is small? What makes them substantively different—or maybe not so different—from “adults,” their parents’ and grandparents’ generations?

Volkov: The main difference is Internet use. Thanks to the rapid development of mobile Internet, practically every young person is an Internet user, regardless of whether they live in a large urban center or in the provinces. This is true of most countries, not just Russia: young people easily master state-of-the-art technologies. The largest gap in the use of technologies is between the youngest and the oldest. The middle-aged are also learning to use them, but very slowly.

Thanks to their digital skills, youth use alternative sources of information, first and foremost the Internet. This makes it possible to say that young people are freer, even though the government increasingly interferes in and imposes restrictions on the Internet, and the idea of a “sovereign Internet” frequently comes up in government discourse. Still, the difference between the youth and others is quite significant, but this hardly affects their political views because young Russians barely have any, as they themselves readily admit. Again, low interest in politics is a universal characteristic of young people, not just those in Russia.

|

“The difference between the youth and others is quite significant, but this hardly affects their political views because young Russians barely have any, as they themselves readily admit.”

|

This difference may be seen as sowing the seeds for change that may or may not occur in the future. For the present, young Russians’ political opinions—whether on Russia’s role in the Ukrainian conflict or Russian military engagement in Syria—are similar to those of the older generation and, therefore, not dissimilar from government propaganda and Russia’s official stance. My understanding is that the older generation watches TV and not too many question what the TV says because few alternative sources of information are easily accessible. Young people pick up their views from older people because they do not have much interest in these matters. If they did, they would probably look elsewhere for information. As a respondent in our focus groups summed it up: “I’d rather surf the Web for something useful rather than news.”

Lipman: Do you think this phrase characterizes the perceptions of the average young person today?

Volkov: I think so. We see it in public opinion polls as well as in focus groups. When we talk to people under 25, TV almost never comes up. We don’t necessarily ask them whether or not they watch TV—what matters is that they almost never mention TV, whether specific shows or TV personalities. This is different among those in the 25-35 age range: in this group, TV is mentioned frequently. This does not mean that the young do not watch TV at all—about half of them still do—but they turn to the Internet more frequently.

Lipman: I was surprised, when looking at your question about popular TV hosts, to find that youth mention those who have been on the screen for 10 or even 20 years—the same ones who are popular with their grandparents and parents…

Volkov: Who else is there? I would also point out that in the public perception, “a journalist” is most likely somebody whom they see on TV. When they hear the word “journalist,” most respondents do not think about people who are concerned with objectivity or credibility; they think of a face on the screen.

Lipman: Are there any new names that have emerged recently that are mentioned alongside veteran TV celebrities?

|

“For some of today’s young Russians, an Internet figure can be as respected as the host of a prime-time news show.”

|

Volkov: Yes, when young people were asked to name journalists whose opinion they respect, about 4 or 5 percent mentioned Yuri Dud’. [Pictured at right, Yuri Dud’ is a 32-year-old journalist who launched his own YouTube channel in 2017 where he interviews prominent Russians. His daring, often arrogant manner and personal, sometimes insulting questions have won him huge popularity. His channel has about 4.5 million regular subscribers.] Older people practically never mention him, but an equal number of young people mention TV veterans such as Vladimir Pozner or Dmitry Kiselev. So for some of today’s young Russians, an Internet figure can be as respected as the host of a prime-time news show. For the rest, and especially for the elderly, news and talk-show hosts on the federal TV channels remain unchallenged.

Lipman: Some liberal online publications identified the new genre of long, in-depth YouTube interviews—Dud’s channel being one outlet for these, but there are also others—as an important media trend in 2018. Is it fair to say that people at large do not notice such trends?

Volkov: Yes, this may be an important trend for journalists, but hardly for people at large.

Lipman: Can you recall anything in your focus groups with young people that was unexpected to you as a sociologist with substantial experience of conducting surveys of Russian society?

Volkov: A couple of years ago, my colleagues and I were struck by the large gap in Internet use. It was at that time that the Internet had outpaced TV among the young. We did not pay attention to this factor until Aleksey Navalny’s rallies of 2017. The fact that those protest rallies brought together a large number of very young people threw sociologists, as well as other experts and the media, into a ferment. Youth became the center of attention. From our point of view, however, the difference between young people and the rest of the Russian population is exaggerated. The fear experienced by law enforcement when very young people took to the streets was unjustified, and the expectations of those who hoped for change were also exaggerated. As I mentioned, our data do not suggest that young Russians are a substantially different constituency that is politically engaged and takes part in civic activism, although it is true that Navalny is the kind of politician who enjoys support, first and foremost, from the young—this much we also see in our surveys.

|

“The fear experienced by law enforcement when very young people took to the streets was unjustified, and the expectations of those who hoped for change were also exaggerated.”

|

Lipman: The young are more likely to support Navalny, but not too many support him even among the young, correct?

Volkov: This is true! But he was able to attract the young and concentrate their support around himself, and that produced a misleading effect. I want to emphasize again that they are less interested in politics than society at large.

Lipman: Is there a differenсe between young people and older Russians in terms of their perceptions of the West?

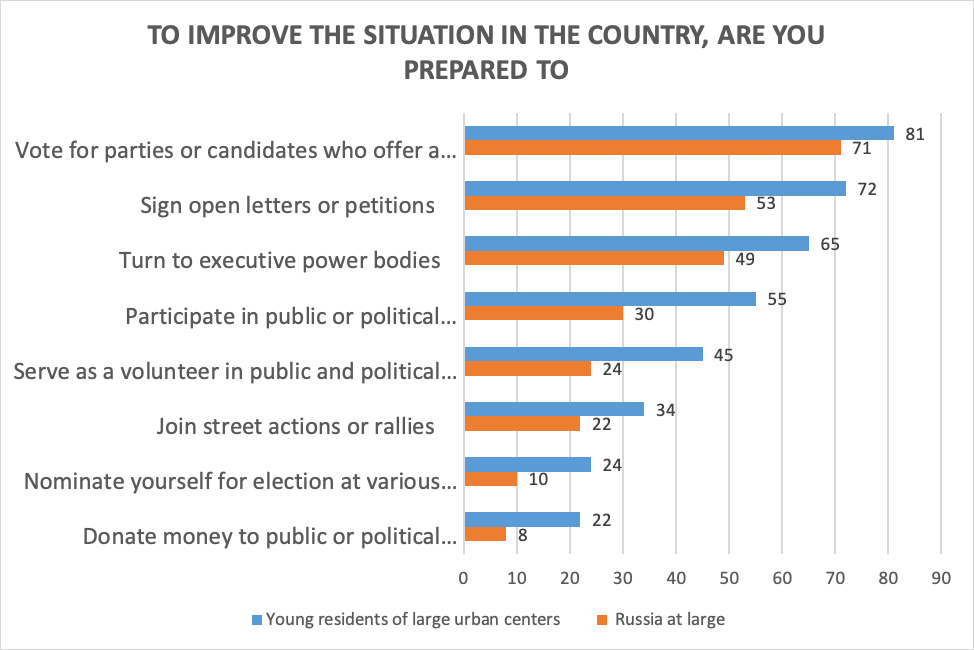

Volkov: Yes, in this respect they are different: the young take a more positive view of the West, the US, and Europe than older generations. In 2014-15, at the height of the conflict in Ukraine, these differences practically disappeared, but today we observe the young and the old diverging more and more. Recently, the perceptions of the youth have become more positive, while those of the oldest group have become more negative (see Figure 2). The gap is widening, but it is hard to say that this trend will not change.

Figure 2.

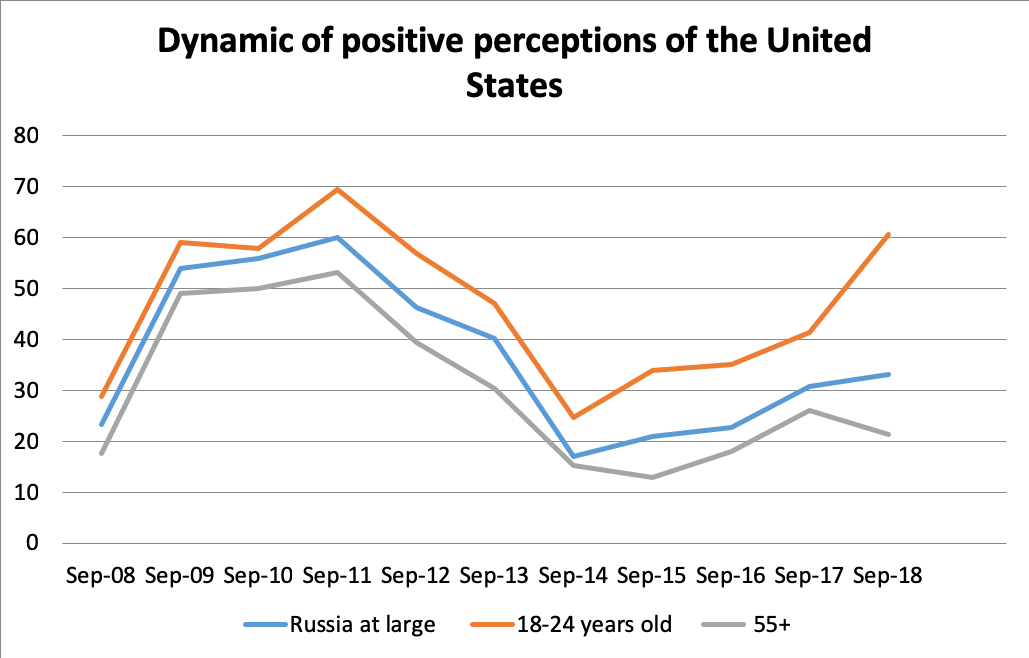

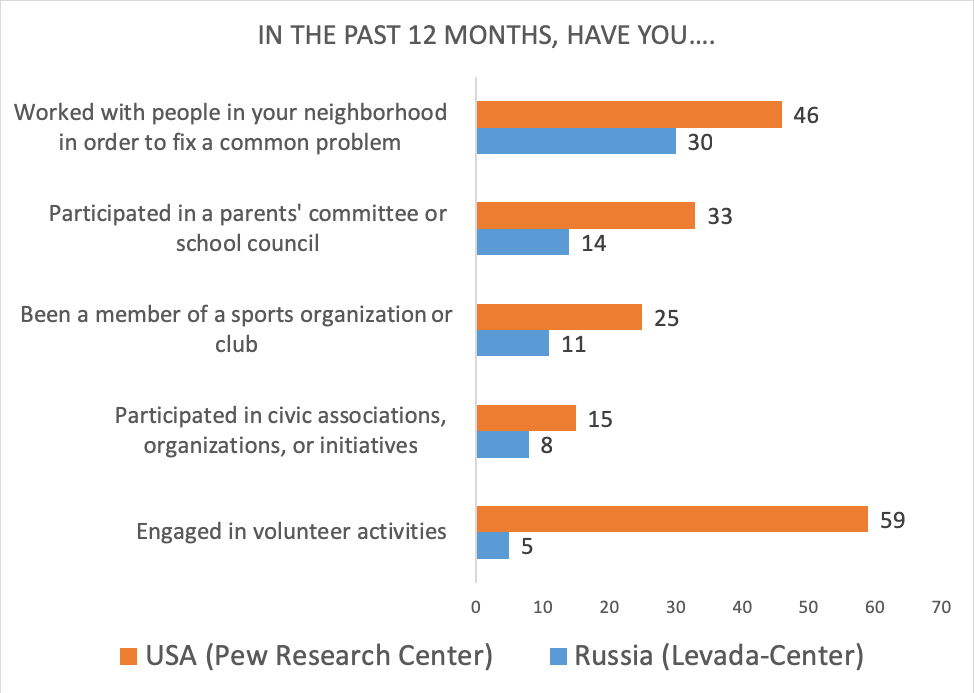

Lipman: Do you have an idea of how the data on civic activism in Russia compares with that on other countries?

Volkov: We have compared our data with that of Pew Research (see Figure 3) The problem is, however, that because societies, social arrangements, and realities are different, it is very difficult to ask identical questions.

For instance, in the US they talk about “school groups.” I am not sure how this should be translated into Russian and whether we have an equivalent of such organizations. Should we compare it with parents’ committees? Or when American pollsters ask their respondents about their participation in community organizations? We do not have “community organizations” in Russia—or if we do, they are called something different or they do different things. This makes it next to impossible to ask identical questions; we have to adjust questions for people to understand what they are being asked about and be able to apply it to themselves. Overall, however, a rough estimate has it that civic activism is about 1.5-2 times more common in the US than it is in Russia. Volunteerism, which is a distinguishing feature of American society, is where the difference is especially great—by an order of magnitude.

Figure 3.

(December 2018, the USA – August-September, 2016)

Lipman: Indeed, 12 times in your figure…

Volkov: In the US, this is an element of their culture. An individual is expected to participate in something of this sort. In Russia, there are no such expectations. This is the problem of quantitative surveys. Even when we make our own questions, without any comparison in mind, sometimes we see that people do not recognize themselves in those questions because they don’t think about themselves in these terms, as in the case of questions about charitable work and donating money, which I mentioned earlier in this interview.

Denis Volkov is a Sociologist and Analyst at the Levada Center in Moscow.