Tatiana Golikova, deputy prime minister for social policy, recently spoke out in favor of informing teenagers about methods of contraception—an unexpected move, given the conservative trend of recent years. (Image cedit: Kremlin.ru)

► Soviet women commonly resorted to abortion as a way to end unwanted pregnancies. In the post-Soviet decades, the emergence of a market economy, the availability of modern contraceptive methods, and increased knowledge about contraception have all contributed to improving sexual culture. The number of abortions has decreased significantly and would have declined even more rapidly were it not for certain issues, among them the absence of a system of sex education. Victoria Sakevich, a Russian demographer, discusses the abortion dynamic in Russia in recent decades in an interview with Maria Lipman, comparing it with abortion rates in other countries.

Maria Lipman: Conservative initiatives related to abortion have become more vocal in Russia in recent years, and we will get to that. But let us begin by drawing a more general picture: what have been the main trends in abortion practices since the collapse of the Soviet Union? In particular, how has the ratio of births to abortions changed?

Victoria Sakevich: There have been substantial—and positive—changes in birth control in the post-Soviet period. Russia, like Western countries, has undergone a demographic transition: today, an average family wants to have two children, and this means that for many years women and couples have to be concerned about avoiding unintended pregnancies. To this end, couples can use various methods of contraception that help prevent pregnancy or use abortion in order to end it.

For decades during the Soviet period, induced abortion played a substantial role in the birth control practiced by Soviet families. In 1920, Russia became the first country in the world to legalize abortion as a woman’s choice. [From 1936 to 1955, abortion was banned; backstreet abortions became common, leading to grave health damage and a sharp rise in maternal deaths.] Since Soviet women did not have the alternative of reliable and secure contraception, they had to resort to abortion as a way to end unwanted pregnancies. The highest abortion rates were registered in the mid-1960s. 1964 set the record: 5.6 million abortions were performed that year—that is, 169 abortions per 1,000 women aged 15 to 49.

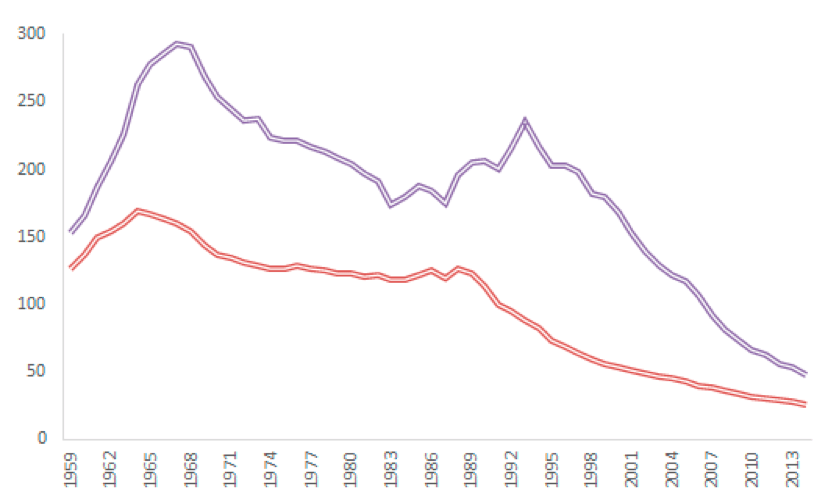

FIGURE 1: The number of abortions per 1000 women aged 15-49 and per 100 live births (Russia, 1959-2014)

KEY: Per 100 Births (purple); Per 1,000 Women (red) | Source: Rosstat data

In the 1990s, the transition to a market economy gave rise to radical changes in many spheres, including birth control. Over the past 20 or 30 years, Russia has made significant progress toward more modern, civilized methods of birth control in which the focus is on preventing unwanted pregnancies, not ending them.

|

“Over the past 20 or 30 years, Russia has made significant progress toward more modern, civilized methods of birth control in which the focus is on preventing unwanted pregnancies, not ending them.”

|

According to official statistics published by the State Statistical Committee (Rosstat), a steady decline in the number of abortions began in 1988; between that year and 2015, the absolute number of abortions registered on an annual basis has decreased 5.5 times, from 4.6 million to 0.8 million. During the same period, the abortion rate per 1,000 women aged 15 to 49 declined by 5.3 times (from 127 to 24). Whereas in the 1960s there were three abortions for every birth, today the number of births is twice as high as the number of abortions.

The total rate of abortions—which provides a more accurate measure, independent of the age structure of women—has gone down from an average of 3.39 registered abortions per one woman during her reproductive age in 1991 to 0.78 in 2015. In the 1960 and 1970s, this index reached an estimated 4-5 abortions per woman of reproductive age.

Unfortunately, I cannot cite more recent statistics because the way of classifying registered abortions in the statistics has changed, and the Rosstat data published since 2015 are not compatible with the earlier data. For the period since 2015, we can analyze the dynamic only of a certain category of abortions, for instance induced abortions before 12 weeks performed by a woman’s choice in hospitals operating under the auspices of the Ministry of Health (such abortions amount to 54 percent of all abortions conducted in the framework of the Ministry of Health; the remaining 46 percent comprises miscarriages, abortions for medical reasons, and some other categories).

These data also indicate that the national level of abortions continues to decrease. During the period between 1992 and 2017, the abortion rate —per 1000 women aged 15-49, performed at the woman’s request and in the case of pregnancies not exceeding 12 weeks—has gone down more than 8 times.

Lipman: In your article published in 2016, you wrote: “The younger generations of women behave differently than their mothers did.” In which age groups has the number of abortions decreased most rapidly, and in which has this trend been slower?

|

“The younger generations of women behave differently than their mothers did.”

|

Sakevich: During the post-Soviet period, the abortion rate has declined in all age groups, but the youngest cohort (up to 20 years old) has demonstrated the most significant decrease. Between 1992 and 2015, the abortion rate in the group of women aged 15-19 decreased 7.3 times, in the 20-34 group it went down 4.2 times, and in the group aged 35 and older, it declined only 3.7 times.

The statistical assessment technique of breaking the population into 5-year age groups, which Rosstat developed between 2008 and 2015, also indicates a more rapid decline in the incidence of abortion among the youngest Russian women: in the 15-19-year-old group, the abortion rate declined 2.7 times between 2008 and 2015, while the overall abortion rate decreased 1.6 times.

FIGURE 2: The decrease of abortion rates by age group* (per 1,000 women of the indicated ages) (2008=100 percent) (without Crimea)

*Without miscarriages | Source: Rosstat data

|

“For the youngest age groups, what can be referred to as the Soviet ‘abortion culture’ is a bygone phenomenon.”

|

As far as teenage abortions are concerned, Russia has moved from the “leading” position among the developed nations to the middle of the ranking. In France, Sweden, Estonia, Great Britain, the US, and a number of other countries, the abortion rate in the 15-19 age group is higher than in Russia. For the youngest age groups, which can be referred to as the Soviet “abortion culture” is a bygone phenomenon.

It is noteworthy that in the youngest age group (up to 20 years old) both abortions and birth rates have gone down in recent years; this means that the incidence of abortion has decreased not because women prefer to give birth rather than end the pregnancy but as a result of more responsible sexual habits.

Lipman: How does the abortion situation look compared to developed countries? And compared to the former Soviet republics?

Sakevich: Two reservations need to be made before we compare the situation in Russia to that of other countries. First, reliable statistics exist only in a limited number of countries, mostly the developed ones. In most developing countries, either the right to abortion is significantly limited or else abortion is banned altogether. Most induced abortions are conducted illegally, such that precise data on the incidence of abortion are absent; only estimates are available.

Second, in Russia, the official statistics include not just induced abortions, but also miscarriages, and the latter’s share of the total number of abortions is rising. In 2017, miscarriages accounted for about 39 percent of abortions registered in clinics operating under the auspices of the Ministry of Health. As a result, the Russian abortion level is inflated compared to other countries, where the official statistics usually record only legal, artificially induced abortions.

I would like to point out that, in our opinion, the Russian government statistics on abortions are rather comprehensive and reliable. Some authors claim that the official statistics are incomplete because the existing network of private medical services do not provide reports about their operations. Non-governmental medical centers indeed do not submit reports to the Ministry of Health, but they are obliged to submit information about their operations to the Rosstat territorial divisions. If they hide any part of their activities, they are in violation of the law and expose themselves to unjustified risk.

|

“If we consider only induced abortions (without miscarriages), today’s Russia is not much different from countries with similar birth rates. We are very close to the level of abortions reported by Sweden, France, New Zealand, etc.”

|

Nationwide sample surveys in recent years have confirmed the reliability of Rosstat’s abortion statistics. The indices calculated on the basis of women’s responses proved to be very close to those published in official statistical reports.

Although some international experts and Russian politicians disagree with my colleagues and me, they have failed to cite any evidence to corroborate their doubts. If we consider only induced abortions (without miscarriages), today’s Russia is not much different from countries with similar birth rates. We are very close to the level of abortions reported by Sweden, France, New Zealand, etc.

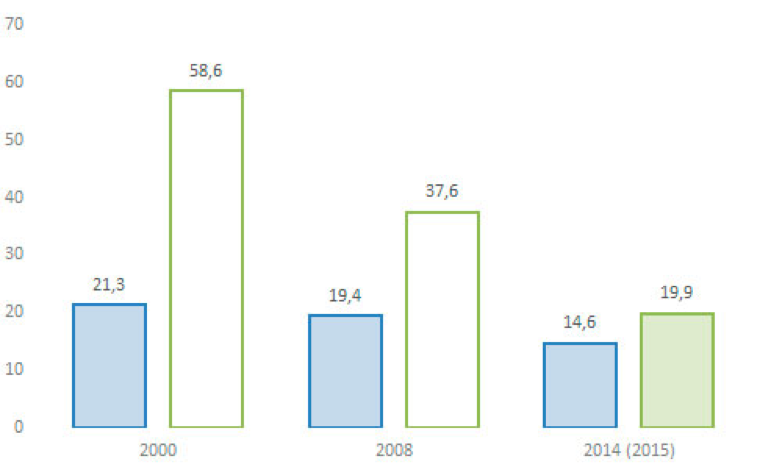

The Russian abortion rate is still higher than that of the US, but the difference is rapidly shrinking. Back in 2008, the Russian rate of total induced abortions was 1.9 times higher than that of the US (1.09 compared to 0.59), but in 2014-15 the Russian rate was only 1.3 times that of the US (0.57 compared to 0.43). The number of abortions is declining in the US, but in Russia, it is declining faster.

FIGURE 3: The number of induced abortions (per 1,000 women aged 15-44)

KEY: USA in Blue; Russia in Green

Compared to the former Soviet republics, Russia still has the highest number of abortions except for the South Caucasus countries. A few years ago, we carried out research with the goal of establishing why the abortion level in Russia had not declined as rapidly as in neighboring Belarus or Ukraine, but we failed to come up with a cogent explanation.

|

“In contrast to what one often reads in the media, Russia does not have the world’s highest level of abortion.”

|

Estonia is closest to the Russian level, while in the South Caucasus countries the incidence of abortions is higher than in Russia, but the statistics of those countries are not very reliable. On the whole, in contrast to what one often reads in the media, Russia does not have the world’s highest level of abortion.

Lipman: Which age groups have the highest number of abortions? Is Russia different in this respect from developed countries?

Sakevich: The highest incidence of abortions (as well as the highest birth rate) is found in the 25-29 age group. As I already mentioned, the abortion rate among teenagers has been declining faster than in any other age group, therefore their contribution to the total abortion rate has also been diminishing rapidly. For instance, in 2008 the contribution of 15-19-year-olds amounted to 10.1 percent, and by 2015 it had gone down to 6.1 percent, while the contribution of women over 30 years old has risen from 42 to 48 percent. Russia is “aging”—this applies to both motherhood and abortions.

What makes Russia different from many Western countries, especially the Anglo-Saxon and Northern European ones, is that in those countries abortions are, as a rule, the result of unintended pregnancies among unmarried young women. In the United States, the largest share of abortions is among the 20-24 age group. The contribution of young women (up to 25 years old) to the total abortion rate in the US is 45 percent, while in Russia it is 28 percent.

FIGURE 4: Rates of induced abortions in Russia and the US by age category (per 1,000 women of the indicated age)

KEY: Russia in Blue; USA in Orange

Russia has fewer abortions among under-25s than the United States does but in the group aged 25 and older Russia’s abortion rate exceeds that of the United States. This means that in Russia women with children are more likely than their American counterparts to resort to abortion in order to avoid another birth. These differences may, in part, be related to the fact that despite the “aging” trend, Russians still tend to form families and begin having children earlier than their Western counterparts.

|

“In the group aged 25 and older, Russia’s abortion rate exceeds that of the United States. This means that in Russia women with children are more likely than their American counterparts to resort to abortion in order to avoid another birth.”

|

Lipman: What factors have contributed to the decline in the abortion rate in Russia?

Sakevich: As a rule, women resort to abortion if they have failed to prevent unwanted conception. The high number of abortions in Soviet Russia was caused by ineffective family planning: put simply, families often failed to control births. In the 1960s-1970s, when a “contraceptive revolution” occurred in the West, the Soviet Ministry of Health emphasized that hormonal contraception had negative effects on women’s health. Couples relied on less effective methods of birth control, such as withdrawal, poor-quality condoms, and douching.

Distrust of modern contraception has not been overcome in Russia to this day. My colleagues and I recently published an article about this.

The five-fold decrease in the abortion rate in the post-Soviet period has been the result of extensive practices of family planning. The emergence of a market economy, the availability of modern contraceptive means, and increased knowledge about contraception have all contributed to significantly improving sexual culture.

|

“The early 1990s state program “Family Planning” played an important role; it provided opportunities to train specialists and improve public knowledge about how to prevent unintended pregnancies.”

|

It should be noted that the introduction, in the early 1990s, of the state program “Family Planning” played an important role. This program introduced a national family planning service; it provided opportunities to train specialists and improve public knowledge about how to prevent unintended pregnancies.

The program was highly successful, but it caused discontent among conservative groups. The State Duma supported the campaign against this program, and in 1998 its budgetary funding was stopped. But the number of unintended pregnancies had already begun to decline, and this dynamic could not be reversed, especially since the campaign did not go as far as banning or restricting contraception.

Lipman: Is it fair to say that contraception as a means of family planning has become the norm? If so, why is it that the overall number of abortions is still higher than in developed countries? Does Russia lag behind in some aspects of family planning—and if so, where is this lag most pronounced?

Sakevich: Yes, family planning has become the norm for the majority of Russians. All recent sample surveys confirm that reliance on contraception methods has become standard practice in Russia.

For instance, in a 2011 survey of reproductive health, 72.3 percent of women aged 15-44 who were married or had a partner had used contraception during the 30-day period prior to the poll. In this respect, Russia is barely different from other countries with a post-transition birth pattern. And yet the general abortion level is still on the high side. This means that in Russia the use of contraception is less effective, which is largely the result of the structure of the contraception methods applied. The most popular mode of contraception used by Russian families is the condom, which is considered to be a method of medium effectiveness, since in real life ideal usage is difficult to achieve. There is no obvious reason why Russians prefer condoms. This would take a special study. One possibility might be an unwillingness to deal with the government health service and a desire to avoid “medical oversight” over one’s private life: a condom can easily be bought at a regular grocery store.

|

“The most popular mode of contraception used by Russian families is the condom, which is considered to be a method of medium effectiveness, since in real life ideal usage is difficult to achieve.”

|

The second and third most popular means of contraception—but still much less common than condoms—are IUDs and hormonal pills. Sterilization birth control, which is the most broadly used method worldwide, is very rare in Russia.

That is, the three most effective kinds of contraception commonly used in those countries that have undergone a contraceptive revolution—hormonal pills, IUDs, and sterilization—are much less common in Russia. In those countries, three-quarters or more of couples rely on highly-effective contraception; meanwhile, in Russia, these methods are used by less than half of couples. A substantial share of Russian families (about 15 percent of women aged 15-44 who are married or have a partner) still draw on so-called traditional methods—that is, withdrawal or the rhythm method.

Lipman: In some countries, contraceptives are fully or partially covered by medical insurance. What about Russia? If they are not covered now, is this at least discussed as a possibility? Are contraceptives expensive for families that are not well-to-do?

Sakevich: Unlike abortions, the use of contraceptives is not regulated by law. The law “On the fundamentals of citizens’ health protection in the Russian Federation” stipulates that Russian citizens are entitled to free counseling on family planning, yet only “on medical indications.” It is not quite clear what this means. The only method of contraception that is regulated by a special article of the aforementioned law is sterilization. The word “contraception” is not mentioned in official documents, and Ministry of Health documents are no exception. Contraceptive agents are not included in the system of compulsory medical insurance. Almost no modern forms of contraception are produced or developed in Russia; as a result, such products are expensive. And there is no system of sex education. This means that as far as family planning is concerned, the Russian people are on their own. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that according to a 2017 Levada Center survey, it is not specialists but friends and acquaintances who are the main source of information about how not to get pregnant.

|

“Almost no modern forms of contraception are produced or developed in Russia; as a result, such products are expensive. And there is no system of sex education.”

|

It is interesting that even though contraceptives are expensive, our respondents very rarely mentioned (un)affordability as the reason why they did not use modern methods of contraception. The primary reason is concern about side-effects. Apparently, this is the result of insufficient knowledge and the absence of professional family planning counseling. It is also possible that the poorest and most vulnerable segments of the population are underrepresented in sample surveys.

Lipman: What do you think of the government’s family planning policy? Which government agencies (besides the Ministry of Health) or non-government (including religious) organizations come up with initiatives in this sphere? Does the Ministry of Health consider decreasing the number of abortions an important task? Is the government more open to progressive or conservative initiatives related to abortion? Which measures—legislative or regulatory—have been adopted or rejected in recent years?

Sakevich: The government’s family planning policy has never been consistent. My colleagues and I have divided the post-Soviet period into three parts: before 1998, from 1998 to 2006, and after 2006.

The earliest period (before 1998) may be described as “auspicious for family planning.” It was associated with the adoption of the federal program of “Family Planning” that I mentioned earlier. The period from 1998 to 2006 was “moderately inauspicious.” Many initiatives were launched that would have tightened abortion legislation (in Russia it remains liberal), yet nearly all of them were rejected. The period after 2006 we define as “archaization and regress.” The lawmakers intensified their efforts to restrict reproductive rights; this also coincided with a new stage of “pro-natalist” policy in Russia, one that is aimed at boosting the birth rate. At this stage Russia’s leadership has chosen to reduce the incidence of abortion, yet not by promoting family planning, but by stimulating the birth rate and creating obstacles to induced abortions.

|

“Russia’s leadership [in recent years] has chosen to reduce the incidence of abortion, yet not by promoting family planning, but by stimulating the birth rate and creating obstacles to induced abortions.”

|

A few legislative amendments have been adopted that reduce access to abortion. For instance, in 2007 the list of medical indications for abortion was cut down. In 2012, the government reduced the list of social indications for abortion to just one: pregnancy as a result of rape. In the 1990s, this list included 13 social indications. In 2011 a so-called “week of silence,” or waiting period, was introduced: when a woman comes to a medical institution seeking an abortion, she is now told to wait for 48 hours or seven days, depending on the pregnancy term. During this time, the woman has to visit an office of medical and social counseling and listen to a psychologist’s or social worker’s advice. The main goal of this counseling is to persuade the woman to change her mind and decide to give birth instead of ending the unintended pregnancy.

And by the way, the Ministry of Health suggested a differentiation between “prevention of unwanted pregnancy” and “prevention of abortions,” even though they are essentially the same thing. The officials, however, propose that the former implies the use of contraception and the latter is aimed at persuading a woman not to end the unintended pregnancy. Today, the activity of the Ministry of Health and public organizations that specialize in anti-abortion topics is focused on such “abortion prevention.”

Since 2012, Russian doctors have had the right to refuse an abortion. Since 2014, it has been forbidden to advertise induced abortion as a medical service. In 2016, the Ministry of Health recommended that a woman seeking an abortion be encouraged to view an ultrasound image of the embryo and listen to its heartbeat. That same year, a new voluntary and informed consent form for induced abortion was introduced. A woman seeking a voluntary termination of pregnancy must sign this form, which now includes frightening information about the possible negative consequences of abortion, up to and including infertility. Meanwhile, the World Health Organization cites abortion as a safe medical intervention—if it is performed by a medical professional in appropriate conditions and by gentle techniques.

Exclusion of abortion from the basic plan of compulsory medical insurance has been also discussed. [The Russian Orthodox Church has repeatedly called for such an exclusion; most recently, this opinion was voiced by the Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church – ML.]

|

“In 2018 the political debates on abortion grew less passionate. Several bills initiated by senator Elena Mizulina (the major anti-abortion fighter) were rejected by the State Duma.”

|

In recent years, the opponents of the right to abortion have added a new argument to their stance: they claim that abortion offends the feelings of religious believers. Many of the abortion-restricting amendments are similar to the recommendations of the Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church. I also believe that many Russian pro-life activists have borrowed ideas from their counterparts in the US.

It should be noted, however, that in 2018 the political debates on abortion grew less passionate. Several bills initiated by senator Elena Mizulina (an ardent proponent of social conservatism and the major anti-abortion fighter) were rejected by the State Duma.

The executive government does not support repressive measures aimed at encroaching on reproductive rights. Tatiana Golikova, deputy prime minister for social policy, recently spoke out in favor of informing teenagers about methods of contraception—which was unexpected, given the conservative trend of recent years.

Lipman: What is public opinion on abortion like today?

Sakevich: According to public opinion surveys, the Russian people do not approve of abortion. Abortion is generally not a decision that is taken lightly or easily. But if the question is whether abortion legislation should be less liberal, then public opinion is divided. More and more Russians believe that a woman’s right to choose abortion should be restricted. In 1998, 18 percent indicated this in a Levada Center poll, and in 2015 this number reached 35 percent. The highest share of abortion opponents is found among those groups for whom the issue of unintended pregnancy is not highly relevant: men, women past reproduction age, young women without the experience of family life. But among believers (or those who identify themselves as believers), there is no consensus on abortion. Fifty-two percent of Orthodox believers and 61 percent of Muslims disagreed that abortions were legal murder and impermissible under any circumstances. An overwhelming majority of adult Russians (78 percent), including believers, share the perception that families should plan childbirth using methods of contraception. Only 14 percent believe that a woman should give birth to and raise as many children as God gives. If Russia held a referendum on whether abortions should be legally restricted, such a measure would likely not be approved by a majority. Russians are generally in favor of policies such as an increase in living standards, sexual education, the development of family-planning services, and including contraceptives in compulsory medical insurance plans.

Victoria Sakevich is a Senior Researcher at the Institute of Demography at the Higher School of Economics, Russia. She has been studying the demography of reproductive health for many years.