(PONARS Policy Memo) Since the Ukraine crisis, political commentators have remarked on the chasm of understanding of events in the post-Soviet region, depending on whether one is consuming news in the “East” (which mostly comes from Russia) or “West” (mostly referring to established media sources in the United States and Europe). One aspect of this information divide, believed to primarily afflict the pro-Russian side, is conspiracy theories. Polls and anecdotes have demonstrated that the Russian public largely accepts conspiratorial claims, such as that the Euromaidan events were a “coup,” that the United States supports “fascists” in Ukraine, and more generally that the West sponsors revolutions to overthrow disliked governments in the region.

Yet post-Soviet citizens are believed to be susceptible to conspiracy belief not only about these contentious geopolitical issues, but more generally as well. For example, 45 percent of Russians agree with the statement that “the world is run by some sort of overarching entity that pulls the strings in governments around the globe.”

This memo uses an original survey to understand the origins of conspiracy theories in two states on Russia’s periphery: Georgia and Kazakhstan. It shows that a number of conspiracy theories are widely believed. However, the country where people live makes a difference: citizens of democratic Georgia are usually more conspiratorial than those in autocratic Kazakhstan, but Kazakhstanis are more conspiratorial when the villain is an enemy of Russia. At the same time, contrary to claims about the importance of Russian disinformation, conspiracism cannot be attributed to Russian media exposure alone.

A Congeries of Conspiracies

Previously, no one has conducted a systematic investigation of the frequency of belief in various conspiracy theories in the post-Soviet region or their potential causes. I highlight three factors that may influence the propensity to see conspiracies: regime type, geopolitical orientation, and exposure to Russian media. I conducted the surveys in Georgia and Kazakhstan because they differ in important ways: First, Georgia is a flawed democracy while Kazakhstan is a consolidated autocracy. Second, Georgia has had fraught relations with Russia and friendly ties with the United States, while Kazakhstan has been closer to Russia and ambivalent about the United States. These factors may affect the tendency for people to endorse conspiracy theories in general, or particular types of theories.

The survey was administered to 1,000 respondents in each country. The primary measure is their level of agreement with one set of generic conspiracy theories (generic statements on the behavior of governments and global actors) and another set of specific conspiracy theories (specific claims that people in both countries would be reasonably expected to have encountered). The generic conspiracy theory questions were borrowed from surveys conducted in the United States and Europe, then winnowed for relevance and adapted to make sense in the local context.[1] The specific conspiracy theory questions were devised by the author based on experience in the field, media reports, and focus groups conducted in Georgia and Kazakhstan in September 2016. The surveys were conducted in March 2017 and consisted of stratified random samples covering all regions of the two countries with the exception of Abkhazia and South Ossetia in Georgia. Russians were oversampled in Kazakhstan. The level of agreement with each statement is measured on a 4-point scale.

The generic conspiracy theories consisted of the following claims:

1. Regardless of who is officially in charge of governments and other organizations, there is a single group of people who secretly control events and rule the world together.

2. The government is involved in the murder of innocent citizens and/or well-known public figures, and keeps this a secret.

3. The power held by heads of state is second to that of small, unknown groups who really control world politics.

4. The spread of certain viruses and/or diseases is the result of the deliberate, concealed efforts of some organization.

5. The government permits or perpetrates acts of terrorism on its own soil, disguising its involvement.

6. The government uses people as patsies to hide its involvement in criminal activity.

7. Experiments involving new drugs or technologies are routinely carried out on the public without their knowledge or consent.

8. A lot of important information is deliberately concealed from the public out of self-interest.

In what follows, I address two questions. First, how conspiratorial are people in Georgia and Kazakhstan overall? Conventional wisdom has it that people outside of established democracies tend to be more prone to believe in conspiracies. According to this logic, democracies have mechanisms of transparency and accountability that deter official malfeasance and reassure people that the powerful will not exploit them. Trust of institutions and other people also tends to be higher in countries with higher income, free and fair elections, and strong civil society, and lower where those elements are lacking, as in the former Soviet Union. Therefore, people from both countries should be prone to endorse conspiracy theories.

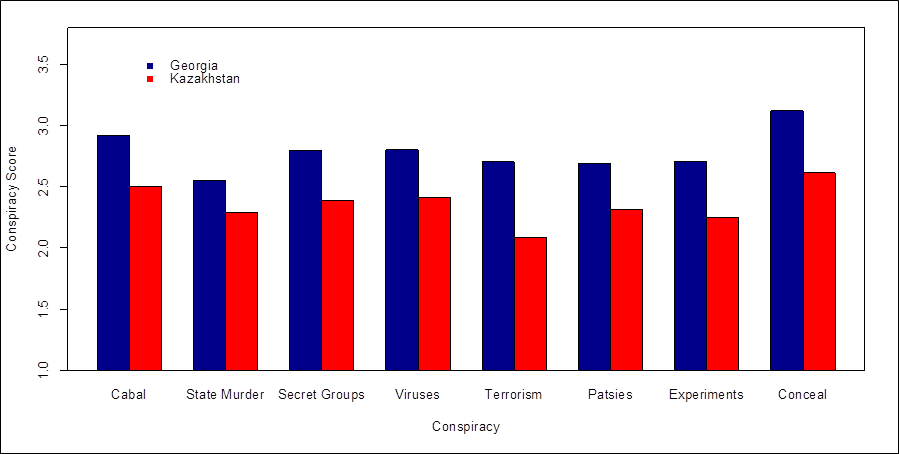

A second question is which country’s citizens are more conspiratorial. Consistent with the argument above, it is commonly thought that conspiracy theories are more prevalent in authoritarian regimes, as dictators use them to distract from their failings and keep people in line, which would suggest that Kazakhstanis should be more conspiratorial. However, competitive regimes present opportunities for a larger number of actors to disseminate messages in the public sphere, and where personality matters more than political programs, there are incentives for politicians of all stripes to promote conspiracy theories—all of which points to Georgians being more conspiratorial. Figure 1 shows the average level of agreement (on the 4-point scale) for each of the generic conspiracy theories, with higher scores indicating greater agreement.

Figure 1: Mean Scores for Generic Conspiracy Theories

The chart shows that most respondents are moderately conspiratorial, with scores lying in the middle range but closer to “probably true” (3.0) than “probably false” (2.0). Strikingly, these questions reveal that the average citizen of these countries is ready to believe that the government murders innocent people and that people are experimented on without their knowledge. The most plausible statement overall, according to respondents, is that information is deliberately concealed from the public, and the least plausible is state-sanctioned terrorism.

Georgians score higher than Kazakhstanis on every question. This indicates that despite Kazakhstan’s authoritarian characteristics across the board (regarding elections, freedom of assembly and speech, civil and human rights, media, political parties, etc.), it is Georgians (considered by Freedom House to live in a “partly free” country) who believe that powerful actors, including their government, are capable of nefarious activities.

A second set of questions places the lens closer to people’s everyday political reality by naming specific actors as the perpetrators of plots. Adding concrete identifiers can reveal whether people believe conspiracy theories in general, or conditionally, for example, only perceiving conspiracies involving an actor or group they dislike. The specific conspiracy theories considered here are as follows:

1 The idea of man-made global warming is a hoax that was invented to deceive people.

2. Regardless of who is officially in charge of governments, media organizations and companies, Masons really control world events like wars and economic crises.

3. Mikhail Gorbachev was really working for the C.I.A. when the Soviet Union collapsed.

4. America supports fascists in Ukraine in order to increase its geopolitical influence.

5. Russia, America, and other powerful countries secretly work together to control world events.

6. The 9/11 attacks on the twin towers were perpetrated by the American government.

7. Regardless of who is officially in charge of governments, media organizations and companies, Jews really control world events like wars and economic crises.

8. America employs local nongovernmental organizations to overthrow governments in the former Soviet Union.

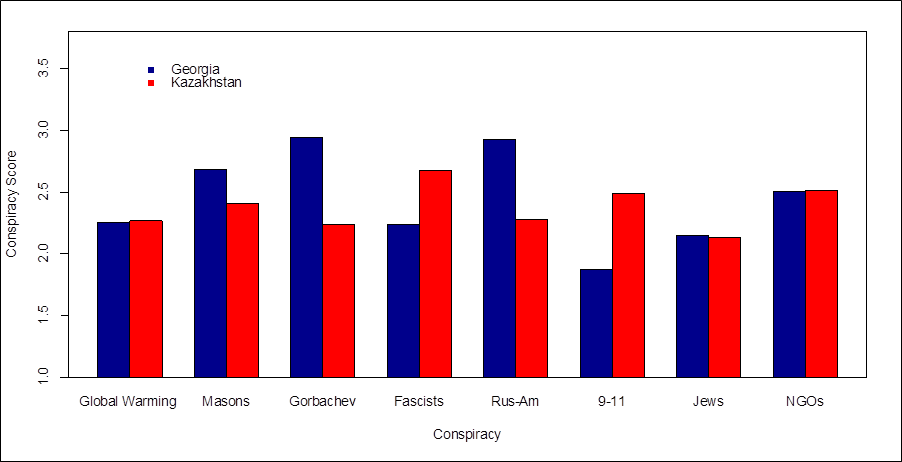

Figure 2: Mean Scores for Specific Conspiracy Theories

Two results initially stand out. First, scores are lower overall than with the generic conspiracy theories, lying closer to “probably false” than “probably true,” albeit still in the same range. Second, Georgians are not more conspiratorial than Kazakhstanis on every question. In fact, both countries score essentially the same on global warming, Jews, and NGOs, while Kazakhstanis score higher on fascists in Ukraine and 9/11. There is an obvious explanation for this: Kazakhstan is both geopolitically aligned and culturally and linguistically integrated with Russia, thus exposing—and predisposing—Kazakhstanis to conspiracy theories heavily pushed by the Russian government. Georgians’ relatively high scores on the American NGO conspiracy do not at first glance fit this narrative. One possibility, observed in this author’s focus groups, is that many Georgians have soured on the 2003 Rose Revolution and, according to an emerging revisionist narrative, place the blame for it (and former President Mikheil Saakashvili’s political ascendance) on the United States and its local proxies.

The difference between the countries regarding the Gorbachev/C.I.A. claim is likely a product of Georgians’ greater dissatisfaction with the status quo compared to Kazakhstanis (borne out in their responses to other survey questions), while notional U.S.-Russian collusion might stem from the tendency of Georgians to feel disillusioned toward both countries. Overall, scores on specific conspiracy theories support the idea that respondents determine the likelihood of a conspiracy theory based in part on their sentiments toward the actors.

When compared to other countries, respondents in the survey are usually, but not always, more prone to see conspiracies. For example, 30 percent of Americans believe that secret groups control world events, as compared with 57 percent of Georgians and 50 percent of Kazakhstanis in the sample (people answering definitely or probably true on generic conspiracies). Another study found that 18 percent of British respondents endorse the global warming conspiracy claim, as against 31 percent of Georgians and 38 percent of Kazakhstanis.[2] On the question of government concealment, the study from which my generic questions were derived found that British students scored 3.86 on a 5-point scale, and this, if we adjust my 4-point scale to correspond with their 5-point scale, compares with 3.9 in Georgia and 3.2 in Kazakhstan. By far the most frequently asked conspiracy question is on 9/11. Polling in the United States shows the percentage of believers ranging from the 20s to high 30s, while a global poll found that 15 percent overall blamed the U.S. government, including 23 percent of Germans and 36 percent of Turks. By comparison, 14 percent of Georgians and 45 percent of Kazakhstanis saw a 9/11 conspiracy. On the whole, a higher percentage of respondents in Georgia and Kazakhstan believe in conspiracy theories than those in the West, but which of the two nations scores higher depends on the conspiracy in question.

Is Russia Responsible?

One possible contributor to conspiratorial beliefs in the region is the influence of Russia, which has worked to project “soft power” through the media, sponsorship of local groups, and leverage over local politicians. Most people in Russia receive their news from television, and respondents in these surveys report the same. Does watching Russian television influence peoples’ beliefs? More concretely, are Russian news consumers in the near abroad more likely to believe conspiracy theories? To find out, I calculated respondents’ average level of agreement across all eight generic conspiracy theories, then compared people who reported watching Russian news in the last week with those who did not. The result? In Kazakhstan, Russian television viewers have significantly higher scores (2.40 vs. 2.31), while there is no discernable difference in Georgia.

What about for conspiracy claims involving geopolitically fraught events? I checked whether news consumption affects beliefs about fascists, 9/11, and NGOs. For Georgia, there is no difference. For Kazakhstan, there is a significant difference only on the question of fascists: 2.77 vs. 2.54. This is the most recent of the three claims to enjoy widespread coverage, so perhaps it has yet to diffuse throughout the population, whereas ideas about 9/11 and NGOs were already established.

But what about nationality? Are ethnic Russians more conspiratorial? Because there are so few Russians in Georgia, it was only possible to test this hypothesis in Kazakhstan, where ethnic Russians comprised 33 percent of the sample. Nationality appears to make a difference: Russians had an average generic conspiracy score of 2.42 as opposed to Kazakhs and other nationalities, whose score was 2.26. This is a highly significant difference. Russians in Kazakhstan are also most likely to endorse claims about fascists and NGOs than non-Russians to a highly significant degree, but there is no difference on 9/11. However, the effect of Russianness disappears when variables measuring orientation toward the state are included: efficacy, institutional trust, government approval, and assessment of how democratic the country is. In other words, Kazakhstani Russians score higher on conspiracy not because they are Russian, but because they are, on average, more alienated from the state than are ethnic Kazakhs.

Conclusion

Although Georgia and Kazakhstan do not speak for the whole region, the results of the survey suggest that belief in conspiracy theories is in fact a common occurrence. But other findings contradict the conventional wisdom. First, democracy is not necessarily a remedy, as evidenced by high conspiracy scores in Georgia and comparable scores on some issues in the United States and Britain. Second, Russian influence may make certain beliefs more plausible but it is by no means the sole cause of conspiracism. In fact, in both countries surveyed there are sufficient reasons for people to believe conspiracy theories without Russian help. While analysts tend to view conspiracy theories in the region through a geopolitical lens, we should not ignore how local political circumstances also contribute.

Scott Radnitz is Associate Professor, and Director of the Ellison Center for Russian, East European, and Central Asian Studies, at the University of Washington.

Research for this memo was supported by the University of Washington’s Royalty Research Fund.

[PDF]

[1] Robert Brotherton, Christopher C. French, and Alan D. Pickering, “Measuring Belief in Conspiracy Theories: The Generic Conspiracist Beliefs Scale,” Frontiers in Psychology, May 2013.

[2] Hugo Drochon and Rolf Fredheim, “Complete Losers: Conspiracy Ideation and Suspicion of Elites in Great Britain,” Working Paper, 2015, 12.