(PONARS Policy Memo) Over the last ten years, the United States has been gradually disengaging from the South Caucasus. This has tremendously affected the countries of the region, especially Georgia and Azerbaijan. The absence of the United States has left the region looking for alternative partners and investors such as Russia, Turkey, Iran, India, and China, with the latter being increasingly attentive toward the region since 2010 primarily due to its Belt and Road Initiative. The Caspian Sea region, already weakened in the West’s purview, saw this trend confirmed with a 2018 treaty that forbids non-littoral states from patrolling the waterway. Turkey, a major presence in the area, has developed into only a luke-warm Western ally. The broader consequence of Washington’s detachment is that initiatives implemented by other actors make the return of the United States to the region—and its projects and plans elsewhere in Eurasia—extremely difficult.

A Diminution of U.S. Attention

The South Caucasus region was considered a geographical focal point for U.S. interests in the 1990s and early 2000s, especially during the advent of U.S. military campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq. When those conflicts ebbed, the South Caucasus lost its significance for Washington and the region was literally left for other rivals. The Trump administration’s isolationism in foreign policy can be seen as a culmination of a decades-long ignoring of the region, a distancing compounded by the EU’s weaknesses of recent years.

With U.S. disengagement and European comparative weakness, the region became lucrative grounds for alternative plans and interests. Moscow, Beijing, and New Delhi have been competing for geopolitical position in the region. For its part, the South Caucasus is hungry for investments and positively assesses attention and especially funds, particularly China’s. While U.S. and Western financial institutions reduced access to capital, China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank has been ready to provide finance for a range of projects. In hopes of expanding their regional influence, Iran and Russia have been more active in the region, and Russia and India have offered joint projects, in particular a north-south transportation system. Finally, the recent signing of a legal framework for sharing the Caspian Sea marks the effort to keep other countries, especially NATO members, out of the region.

No U.S. Presence in the Belt and Road or North-South Corridor Initiatives

Historically, China has not had many interests in the region. Distance, along with the region’s unpredictable political and economic conditions, precluded Chinese penetration. In comparison with Central Asia, South Caucasus markets are marginal, populations are low, and investment opportunities are challenging. Beijing was involved in only a few oil projects, mostly for representational purposes rather than economic benefits. Moreover, active U.S. involvement in the region and Moscow’s zealous attitude toward Chinese regional involvement kept Beijing at arm’s-length.

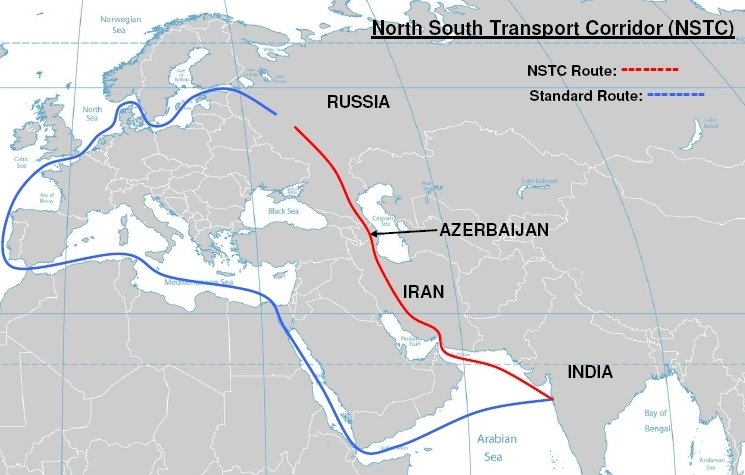

However, about eight years ago, China began to look at the region from a different angle. With the launching of its Belt and Road Initiative (formerly One Belt, One Road), China began to pull the region into its orbit. It launched the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which can finance (transportation) projects in the region. Chinese President Xi Jinping announced that an additional $124 billion would be invested into the Belt and Road Initiative, with funding allowances to provide assistance to developing nations along the route of the large project (see Figure 1). In 2016, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank extended a loan of $600 million for the construction of the Trans-Anatolian Gas Pipeline (TANAP). Although the amount is not huge relative to the total cost of the project, it marks the visibility of China’s interest in the region. The Chinese initiative looks most beneficial from a purely economic perspective. At the time, the region urgently needed a partner that could fill the vacuum left by an increasingly disengaged West.

Figure 1. Routes of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (Source)

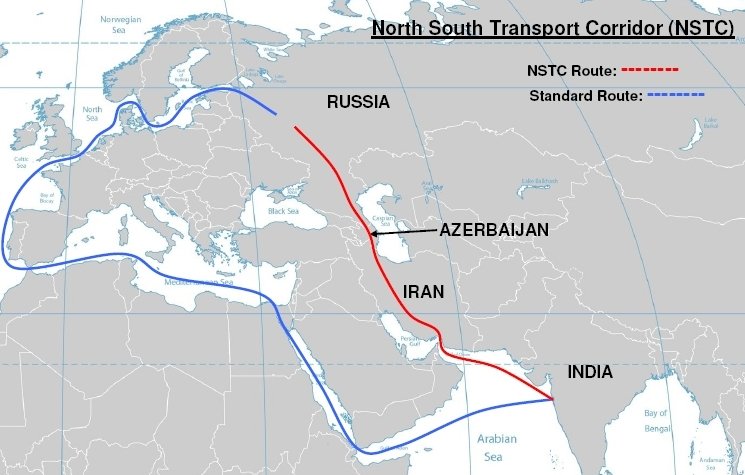

The Azerbaijani and Georgian governments hoped that land routes and high-speed rail links connecting East Asia and Europe would bring in Chinese investment and curb Russian influences. Baku invested heavily in the construction and enhancement of the port city Alyat, “the Jewel of the Caspian,” to include an international logistics center and a Free Economic Zone. Georgia made necessary investments in the ports of Batumi and Poti. From their perspectives, both Moscow and New Delhi were zealously trying to build up infrastructure initiatives to increase export potentials as well as to get cheap and easy access to Europe. The International North-South Transport Corridor (NSTC) initiated by Moscow, New Delhi, and partly by Tehran, is a trade-transport network composed of rail, road, and sea routes that starts in Mumbai, India, goes through Bandar Abbas, Iran, to Baku by railroad or the Caspian Sea, and onward to Russia and Europe (see Figure 2). The initiative was launched back in 2000 and signed by Iran, Russia, and India in St. Petersburg. However, for many years before its rebirth in 2014-2015, the initiators and countries of the region did not show interest in the project.

Figure 2. The North-South Transport Corridor Initiative (NSTC) (Source)

A major north-south trade corridor in this location is not a new idea. During Soviet times, such a corridor existed to transport goods between India and the USSR, but it significantly deteriorated after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Over the last decade, cargo transportation via this route has increased dramatically. The main advantage of the NSTC is the lower cost of transportation from Europe to India and back. A container sent from India to Helsinki by current routes would reach its destination within 45-50 days, while the NSTC can cut this travel time almost in half. Moreover, costs would be lower. A test conducted in 2014 from the Nhava Sheva port in India using two trade routes, one to Astrakhan, Russia, via Bandar Abbas and Amirabad, and another to Baku, Azerbaijan, via Bandar Abbas and Astara, shows that both of these routes can reduce shipping costs by $2,500 per 15 tons of cargo. Analysts say that really only Russia would receive hundreds of millions of dollars from transportation fees, taxes, and custom revenue. Still, the project should increase Russian trade with India by cutting the cost of transportation. It will also allow Moscow to take more active “positions” toward India (and Iran). Further, amid Western sanctions, it is a good opportunity for Russia (and Iran) to find new markets for exports and substitutes for European imports.

For India, the project is vital and beneficial in all aspects, especially taking into consideration that Chinese-led and -constructed infrastructure projects try to exclude New Delhi from participating in them. The NSTC would allow India to get access not only to Europe but also to Central Asia and the Caucasus. Moreover, India may get a share of the Russian market that is currently dominated by Chinese companies. Iran and Russia are the other major players in this project. Both of them are trying hard to diminish the impact of Western sanctions and get additional opportunities to earn needed cash. It is interesting to mention that, in contrast to many other projects in Eurasia, the NSTC is more economically rather than politically driven. All participating sides have mentioned the economic and trade benefits rather than any political or military aspects.

The absence of U.S. involvement in both of the OBOR and NSTC projects is noticeable. Since the end of the Soviet Union, all major projects in the region that drove the countries toward the West were done or implemented with active U.S. involvement. The development of the multi-billion dollar oil fields of the Caspian Sea, construction of the Baku-Supsa and Baku Ceyhan oil pipelines, the first stage of the Southern Gas pipeline, and many others, would had not have been implemented without support from Washington, DC. Beyond economic benefits, those types of projects strengthened U.S. soft power in the region, spurred investments into other areas of the economy, and brought the region closer to the EU and NATO. Not only do the OBOR and NSTC projects give benefits to the countries of the region, they strengthen the soft power of China, Russia, India, and Iran into regional affairs. Taking into consideration that three out of the four mentioned countries are considered rivals of the United States, we can expect a further drift of the region away from the West (EU, US, NATO) and toward the economic and military blocks initiated by these countries.

Security Disengagement

Along with U.S. disengagement and EU weakness, conflicts in the South Caucasus have entered a new phase: from being frozen to being manipulated. Starting in 2008, the United States has seemed to distance itself from active involvement in the security affairs of the region. The U.S. policy of “reset” (perezagruzka) with Russia after the five-day Russian-Georgia war was considered by the South Caucasian governments as a kind of recognition that the region is not deep in U.S. interests. For the whole Obama administration and so far during Trump’s administration, the United States did not bring forth any initiatives to resolve local conflicts or play a mediating role. Instead, Russian influence has steadily and slowly grown, including Russian soft power in the form of Russian media, businesses, and culture. Meanwhile, the Russian establishment is hardly interested in the resolution of local conflicts and even makes use of current situations.

While it is crystal clear that Moscow intends to keep the Abkhazia and South Ossetia conflicts under its control, the Karabakh conflict still remains a bargaining chip. The Kremlin masterfully uses the conflict to militarize the region. Over the last couple of years, Russia has sold billions of dollars’ worth weapons and armaments to both sides, Armenia and Azerbaijan. Thus, transferring the Russian Iskander missile systems to Armenia has sparked another wave of militarization in the region, leading to Baku purchasing the Belorussian Polonez system. Thanks to monopolization of the conflict, Moscow was able to retain Armenia in its orbit through its military base, and keep Azerbaijan from its NATO aspirations. Moreover, it was Moscow that stopped the April War, the 2016 military escalation in Karabakh that led to hundreds of dead and injured on both sides. In any case, the Russian military complex and establishment hugely benefit from the absence of conflict resolution and the absence of balance in the region, fueling the growing Russian appetite.

Finally, the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) is also making progress in becoming a strong military organization and admitting new members. Ali Huseynov, chairman of the parliamentary commission on state-building in Azerbaijan, made a surprising statement on the possibility of considering issues related to Baku’s possible joining of the CSTO. There are a lot of speculations about this statement, including a view that the chairman is expressing his own opinion and not that of the government. But a few years ago, such statements would had been considered treasonous and the mass media and officialdom would had thrown an avalanche of criticism on such a proposition.

Caspian Sea 2018: Foreigners Not Allowed

Since the 1994 signing of the so-called “Contract of Century” between the Azerbaijani government and a consortium of foreign oil companies, the U.S. administration has had particular interests in the Caspian region. The U.S. administration was vital in constructing the pipelines that go from Azerbaijan through Georgia to Turkey. It was also equipping the Azerbaijani and other littoral governments with the necessary techniques and armaments to control their Caspian Sea borders as part of an effort to curb Iranian influence. The U.S. administration had even announced, a while ago, that the Caspian Sea was a region that was part of U.S. national interests.

As it developed its natural resources, the status of the Caspian Sea has been a thorny issue for Baku. Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Azerbaijan were always wary in negotiations about the degree to which the interests of Russia and Iran were incorporated. In the absence of U.S. and EU involvement, Russia initiated and made possible an agreement, on August 12, 2018, that settled the legal status of the Caspian Sea. In the Kazakh city of Aktau, leaders from the five countries signed the agreement, which is supposed to ease regional tensions and speed up development of oil and gas projects. The final text, however, failed to address the issue of partitioning the seabed where most of the oil and gas reserves are. Russian President Vladimir Putin, who pushed for the convention, said the deal had “epoch-making significance” and called for more military cooperation among the countries that border the sea. The most interesting clauses in the agreement are those that stipulate the prohibitions and allowances of other countries’ activities in the Caspian Sea. Clause 6 of Article 3 of the agreement states that armed forces not belonging to the countries of the Caspian Sea cannot be present. Furthermore, it can be technically interpreted that Russia is allowed to establish military bases in any country of the Caspian Sea. Clause 11 of Article 3 states that navigation in, entry to, and exit from the Caspian Sea can be done exclusively by ships flying the flag of one of the five countries. One of the positive parts of this framework is the ability of the bordering countries to lay submarine cables and pipelines on the bed of the sea. This clause opens the way for Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan to export their energy resources to Europe through Caspian gas and oil pipelines via Azerbaijan.

Figure 3. The Countries of the Caspian Sea (Source)

The 2018 Caspian Sea convention can be considered as a victory for Russia due to the agreement’s ban on foreign militaries, which gives Moscow de facto control over that region. Russia’s security benefit here means that the United States, NATO, and China will have a hard time justifying any entrance to the region, even in the realm of combatting terrorism assistance. Russia already showed its position when in 2015 it used its Caspian navy to fire missiles toward Syria. Russia is allowed to build military cooperation with Iran and gain direct access to its southern neighbor through the sea. A few days after signing the agreement, Russian defense minister Sergei Shoigu visited Dagestan and announced the transfer of Russia’s Caspian Fleet to Kaspiisk, which makes it the largest base in the region. With this base and the Russian militarization of the Caspian, Moscow will control many regional transportation routes and block the presence of foreign powers, making it now a region of Russian influence. Any presence of NATO or U.S. troops even on the shores of the Caspian will be considered a violation of the agreement.

Conclusion

There is no sign that U.S. policies toward the South Caucasus will change in the near future. Even the October 2018 visit of U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton to the South Caucasus is mostly connected to perceived security threats from Iran rather than genuine recognition of the region as a place of vital U.S. interests. Perhaps in a telling sign of this, none of the South Caucasus countries—Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia—have U.S. ambassadors appointed.

U.S. disengagement from the region has allowed Russia, Iran, China, and India to make penetrations. The worsening of relations between Turkey and the United States further contributes to the weakening position of the United States in the region. In the past, many Turkish regional interests would have coincided with U.S. interests, and Ankara would have conducted policies with Washington, but as of the last couple of years, this is no longer the case. In some instances now, Ankara cooperates directly with Moscow and Tehran.

It is important that the West recognize that the South Caucasus and Caspian Sea region holds an important geographical and geopolitical position within the security paradigm of the post 9/11 period. It is a transportation and economic hub, important for the security and stability of Europe, and it can be a borderland region for the EU and United States to expand soft power in the Middle East and greater Eurasia. Finally, Western involvement in the region may be more important now than ever considering the growing polarization in world politics. If the West continues to disregard the region, not only the Caucasus, but Central Asia and other parts of Eurasia could very well fall to the policy plans and military arrangements of rival powers.

Anar Valiyev is Associate Professor at ADA University, Baku.

Research work for this policy memo was funded by the UK Research and Innovation Councils (UKRI) under the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) COMPASS Project (Grant number ES/P010849/1) led by the University of Kent.

[PDF]