(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) Great power assertiveness is back, with Russia once again playing a leading role. This memo introduces some new data sources—in the form of uniquely rich automated event datasets—that offer unprecedented promise to start tracking the empirical evidence behind this assertiveness in more detail. In what follows, we draw on these new data to provide unprecedented documentation of Russia’s growing assertiveness over the past decade, including in comparative terms, uncovering important nuances in the process.

The next step in this new data-intensive research agenda will be to start modeling what drives great power assertiveness and what the international community might do to deal with elevated levels of it. As we await new insights from this modeling effort, we attempt to infer and “translate” possible courses of action from the far richer evidence- and knowledge-base about a similar phenomenon: school bullying. Our recommended actions include: monitoring and exposure, puncturing pathos and promoting perspective, mobilizing moderation, stepping up early to a “light” mode of crisis management, encouraging UN Chapter “VI-and-a-Quarter” efforts, and, finally, organizing “adult supervision.”

Great Power Assertiveness Is Back

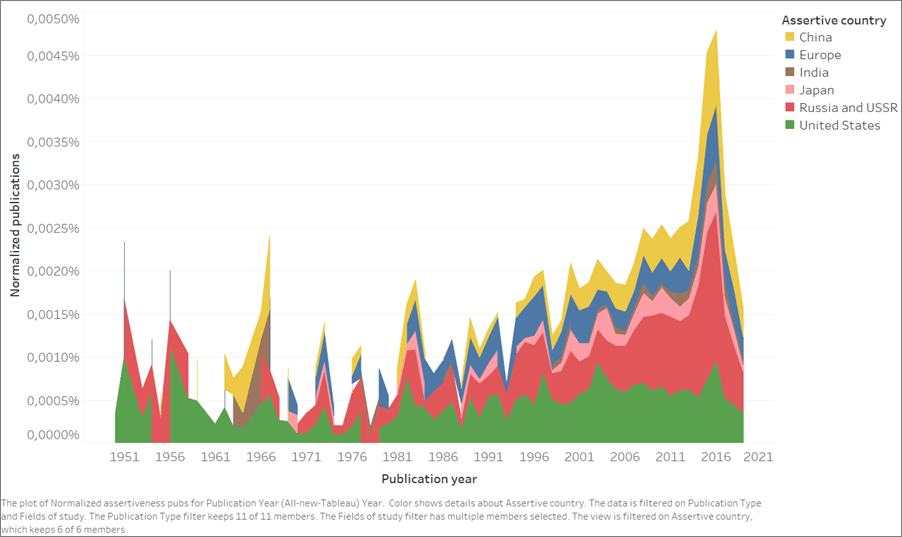

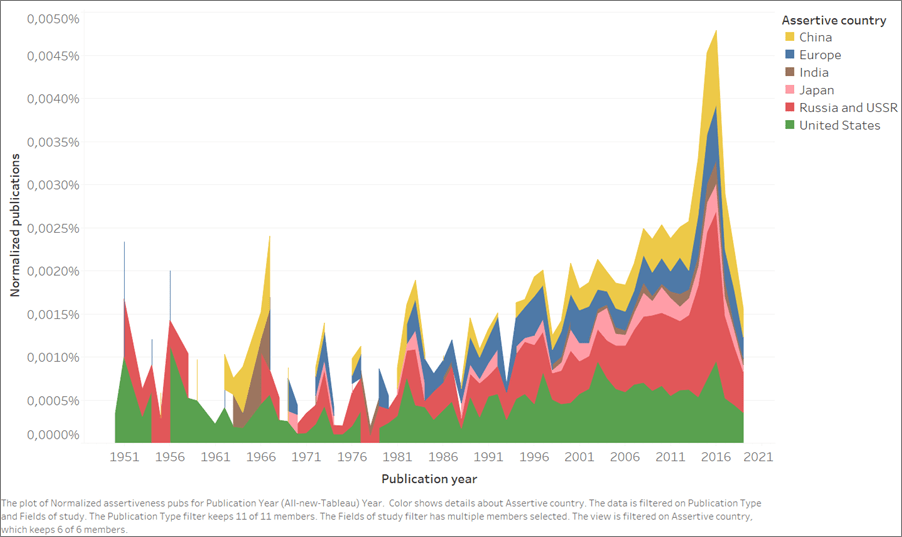

Great power assertiveness has once again become an ascendant theme in global scholarly and policy debates, with Russia positioned as the main protagonist. The number of scholarly publications on this topic, broken down by great power (see Figure 1), reveals that the academic community has become much more focused on great power assertiveness in the current “Second Cold War” period than during the first. After a peak in 2016, overall scholarly interest starts declining again.

Figure 1: Breakdown of Great Power Assertiveness Studies by Subject Country, 1951–2020 (Normalized by All Academic Publications in a Respective Year, Lens.org) Note: The (normalized) dataset visualized here was extracted from the largest free and open bibliographic database, The Lens, based on the following search query: abstract: (assertiv* OR aggress*) and Russia and (“foreign policy” OR “defense policy” OR “defence policy” OR “security policy”).

Note: The (normalized) dataset visualized here was extracted from the largest free and open bibliographic database, The Lens, based on the following search query: abstract: (assertiv* OR aggress*) and Russia and (“foreign policy” OR “defense policy” OR “defence policy” OR “security policy”).

The six great powers in the figure above include the world’s five largest economies today (in nominal terms) plus Russia, in light of its territorial size and continued (and resurgent) military, including nuclear weight. We also observe that Russia (in red) took over from the United States (in green) assertive dominance in the inter-cold-war period with the first peak in 2008 (the August war with Georgia), and then a much bigger and protracted peak since 2014 (mostly events in Ukraine and Syria, but also cross-domain interference in other countries). This was followed by a return to pre-2014 levels during 2018 and the first half of 2019 (the attack in the Kerch Strait in November 2018 being the exception). It is striking that Russia plays a relatively bigger role than, for instance, China.

What Do the Event Data Say?

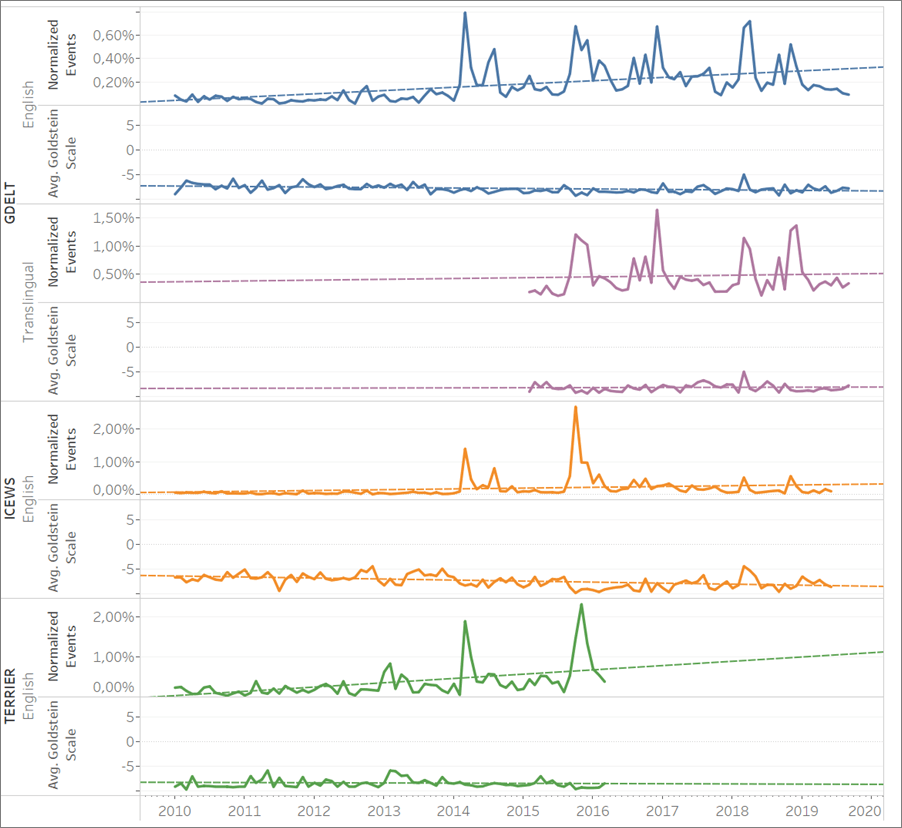

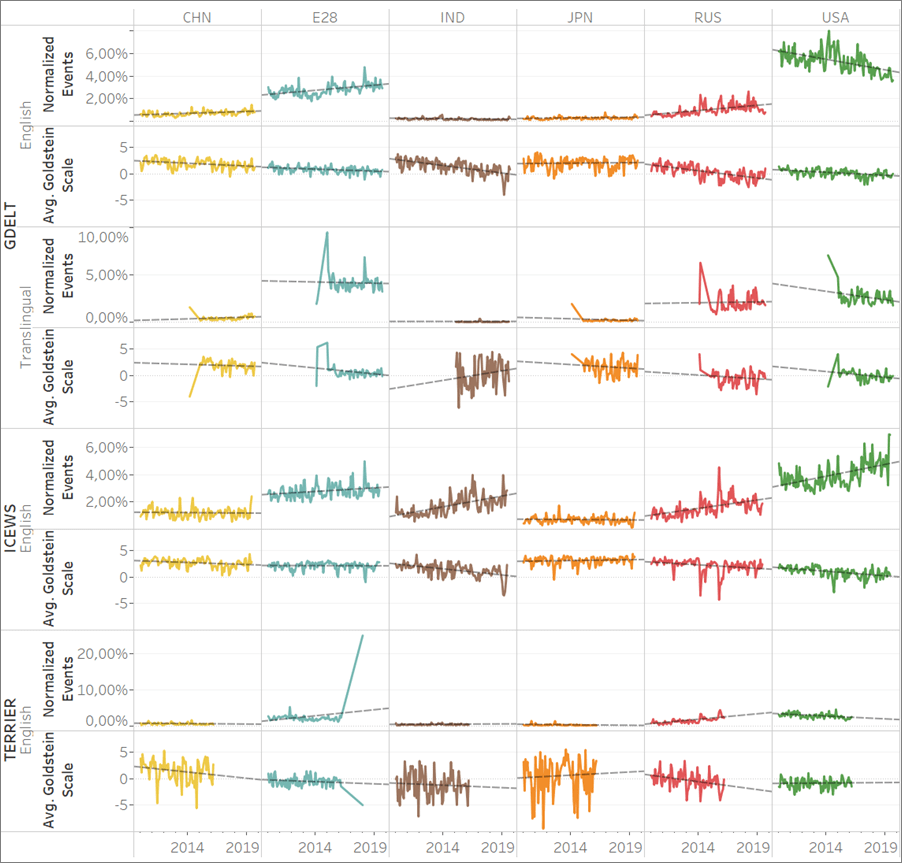

Against the background of increased scholarly attention, what do we actually know about the reality of Russian assertiveness? This memo presents new data on this based on four different automated event datasets that, usefully, all use the same[1] event coding scheme (CAMEO),[2] which enables analysts to compare and analyze their findings: GDELT (both English and Translingual), ICEWS, and Terrier.[3]

This section reports some interesting recent findings on Russia’s factual negative assertiveness, where factual refers to “real-life” (not rhetorical) events and negative means conflictual assertiveness. An example of such assertiveness would be an event with Russia as the source actor, the event code “Fight with artillery or tanks” (making it a factual, negative, and assertive event), and any target actor (for example, Ukraine).[4]

We use two main metrics in our visuals. The first one is quantitative. It measures the number of reported Russia-initiated internationally assertive events as a percentage of all inter-state events.[5] A higher proportion of reported events in this category suggests increased assertiveness. The second metric is more of a qualitative nature. It is based on the so-called Goldstein scale, which assigns every event code a score from -10 (such as a military attack, clash, or assault) to +10 (such as a military retreat or surrender).

Averaging these Goldstein scores per country per month allows us to gauge whether Russia’s assertiveness is mellowing (if the score goes up) or hardening (if it turns downwards). The nature of the event codes also allows us to differentiate between factual and verbal events, as well as between diplomatic, economic, and military ones. Figure 2 below contains the data for Russia’s factual negative assertiveness during this decade as recorded in the four event datasets.

Figure 2: Russia’s Factual Negative Assertiveness, 2010-2019 (Normalized by All Inter-State World Events) Note: We do not include the Phoenix dataset as its coverage is too patchy for this decade.

Note: We do not include the Phoenix dataset as its coverage is too patchy for this decade.

Most of the event datasets concur that both the quantity and the quality of Russia’s international assertiveness have taken a turn for the worse over the past decade (more assertive events with more negative scores). They also show, a point that may be less widely appreciated, a marked (again, both quantitative and qualitative) decline in this assertiveness in the past year, returning the country to its pre-2014 assertiveness level.

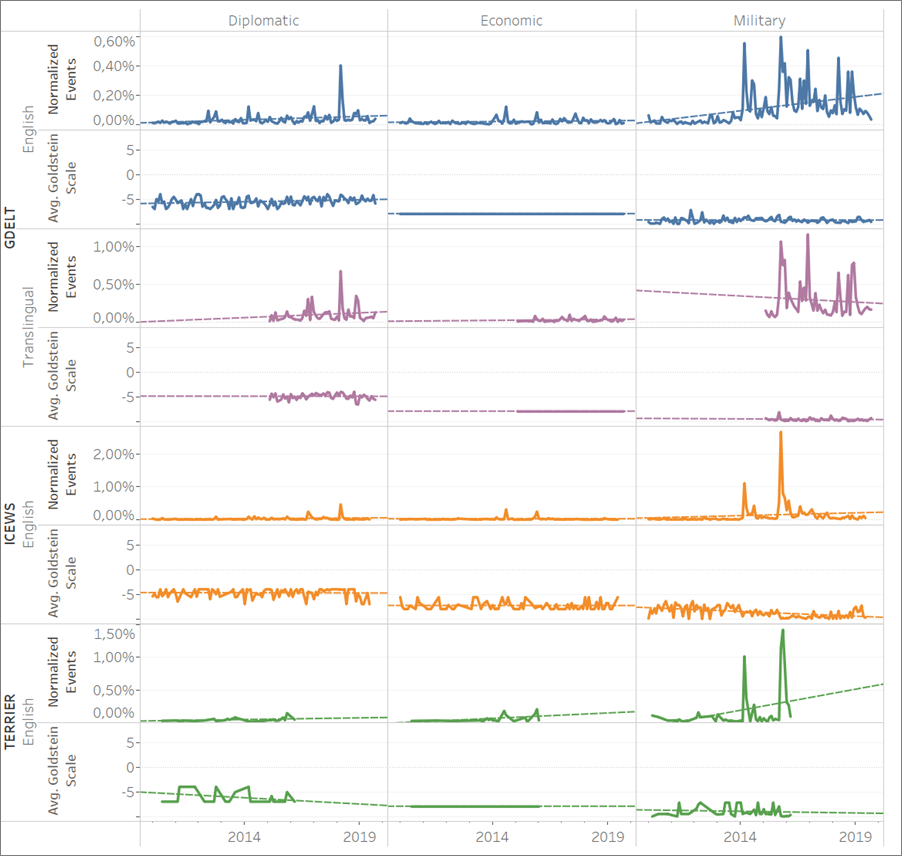

If we compare the data on Russia with the equivalent data for other great powers, we see that Russia, the United States, and the United States’ European allies have militarily been the most assertive geopolitical actors (see Figure 3). While the events involving all great powers tend to have low average Goldstein scores, the quantity of normalized events for these actors is the highest.

Figure 3: Comparative Negative Factual Military Assertiveness of the Great Powers, 2010-2019 (Normalized by All Inter-State World Events)

Event datasets allow for an even deeper dive into assertive events by functional categories. Figure 4 shows the breakdown of Russia’s negative factual assertiveness into diplomatic, economic, and military categories.

Figure 4: Russia’s Overall Factual Negative Assertiveness by DISMEL, 2010-2019 (Normalized by All Inter-State World Events)

This figure clearly shows that the military domain has played a dominant role in the Russian assertiveness story over the past decade, with particularly notable peaks related to events in Ukraine and Syria. Russian assertiveness in the diplomatic (and even more so in the economic) domain remains significantly more subdued, except for a peak in March 2018 related to the Skripal affair and the tit-for-tat expulsion of Western diplomats.

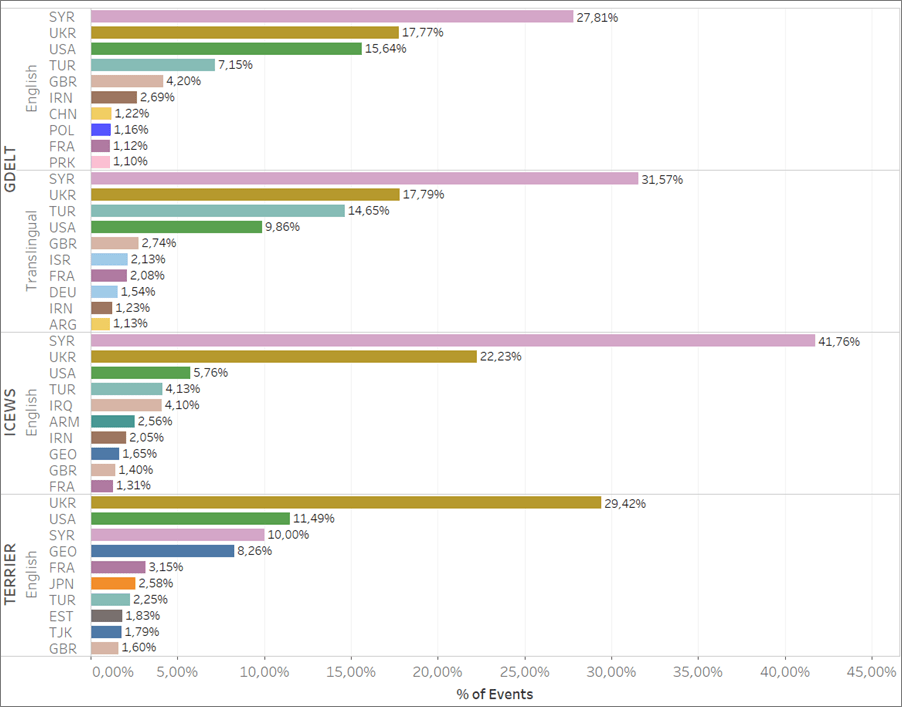

We can also disaggregate the data dyadically to find out which countries have been the preferred targets of Russian assertiveness. We observe that in all datasets, the United States, Ukraine, and Syria have been Russia’s top targets throughout this decade. In all these cases, military assertiveness prevailed over all other types of assertiveness.

Figure 5: Top-10 Targets of Russian Negative Factual Assertiveness, 2010-2019 (by Dataset; Normalized as % of All Negative Factual Assertive Events Where Russia is the Source Actor)

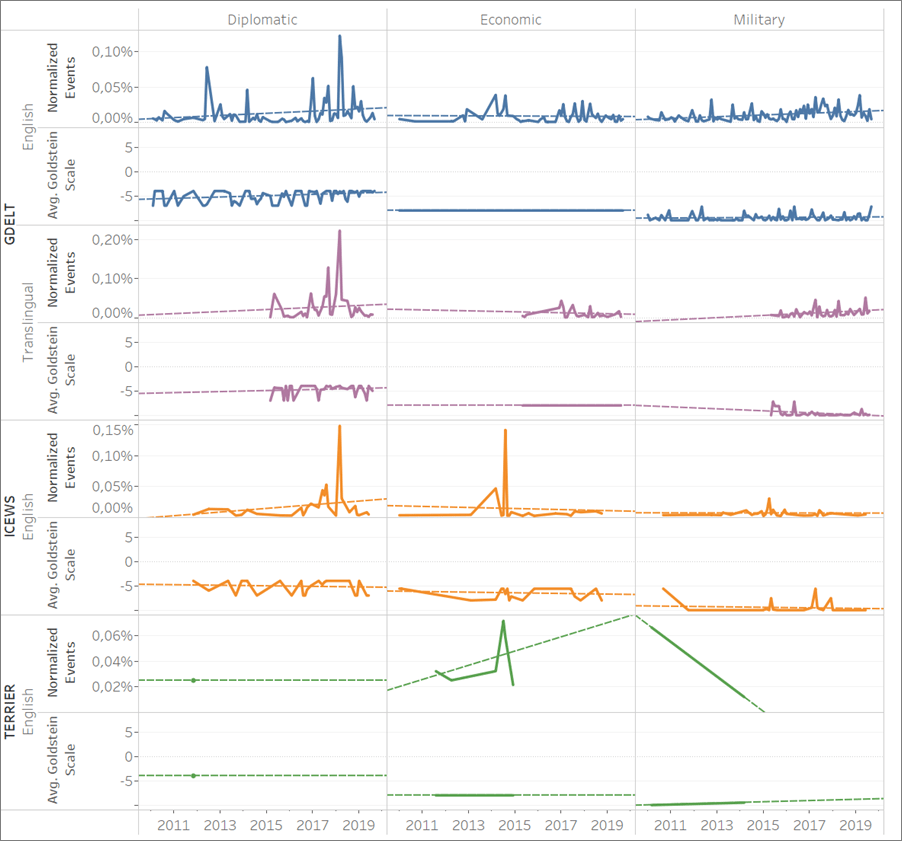

The dyadic Russia-United States data in Figure 6 (below) suggest a decrease in the number of Russia’s assertive events since the start of the Trump administration as well as a less negative tone. Military events have also played a much less dominant role in Russia’s reported behavior towards the United States than towards other top-targeted countries.

Figure 6: Russia’s Factual Negative Assertiveness Toward the United States, 2010-2019 (Normalized by All Inter-State World Events)

How to Deal with Russia’s Assertiveness?

This section offers a few attempts to translate findings from an analogous field with a much stronger empirical base—school bullying—into possible courses of action that our Ministries of Foreign Affairs and our defense and security organizations might want to take into consideration.

Monitor and expose dangerous great power assertiveness

Given the unique role that great powers play in world affairs and the escalatory dangers that lurk behind various forms of (especially military) assertiveness, any effective strategy for dealing with great power assertiveness requires a fine-tuned sensing mechanism that allows the international community to ring the alarm bell as soon as certain observable thresholds are crossed. Our own attempts at monitoring great power assertiveness suggest that it is increasingly possible to flag “excessive” brinkmanship based on detailed evidence. Authoritative international organizations such as the World Bank, IMF, WTO, and OECD already perform analogous international monitoring work in areas like economic, education, health, trade policy, etc. It seems unlikely that our current international security organizations (NATO, OSCE, African Union, UN, etc.) would be willing to assume such a role. It may prove possible, however for our epistemic community to team up to provide the international community with such a capability—not primarily to “name and shame,” but to let the facts speak for themselves.

Puncture pathos and promote perspective

Negative assertive behavior is regularly couched in emotional verbiage about past endured injustices, unfair treatment, misunderstood actions, and the like. Whether such allegations are legitimate or not can only be established by disassembling them into fact and fiction with surgical precision. If the international community wants to make progress in this area, it stands to reason that it will have to find more reliably neutral ways to puncture such pathos with facts and figures—also toward the societies on all sides that are subjected to various distorted or one-sided narratives. This may again be an area where dispassionate epistemic communities from various countries could play a uniquely positive role.

Mobilize moderation

Most societies (like individuals) carry in themselves the seeds of both moderation and excess. Societies that are being swept up by internal or external political entrepreneurs into bouts of jingoistic fervor typically still contain silent majorities that simply condone or go along with these excesses (as well as smaller groups that might actively resist it). In this day and age of global connectivity, it is more possible than ever before to reach and empower the healthy fibers of societal resilience that are embedded in those groups or even individuals.

Step up early to a “light” mode of crisis management

As the educational “assertiveness” literature suggests, interventions need to target the bully at multiple levels, addressing the overall—social or otherwise—context in which the bully operates, directly taking the bully on and trying to change their incentive structure. Firm sanctions are not to be shied away from. In the realm of international relations, this means that one should consider aggressive assertive behavior as a first step on a crisis escalation ladder. This recognition implies that one should start by applying crisis management procedures and techniques. However, stepping up into a crisis management mode should be seen as a flexible, smooth, and unobtrusive process, and not as an assertive, escalatory move in itself (hence the word “light”).

Energize UN Chapter “VI-and-a-quarter” efforts

The international community currently does not have the wherewithal to take a firm stand against assertiveness. It can—and often does—condemn certain actions by great powers. But the debilitating Security Council veto powers held by some of the very same great powers that our data show to be among the worst “culprits” mean that such words are virtually doomed to remain idle. The UN Charter currently includes only Chapter VI—the peaceful resolution of disputes by diplomatic or judicial means—and Chapter VII—peace enforcement related to military operations. Over the past few decades, however, the term “Chapter VI-and-a-Half” has become popular as a “solution” situated between UN Chapters VI and VII. It was coined by former UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld to cover the numerous and quite successful peacekeeping operations that had been carried out under the UN flag. Would it be conceivable to also start thinking about a Chapter “VI-and-a-Quarter” whereby the United Nations, once an ascertained level of assertiveness by a great power crosses a certain predefined threshold, could step up its resolution efforts?

Organize “adult supervision”

All major (and not-so-major) players in the international system—including private companies, NGOs, cities, etc.—are affected by growing great power assertiveness. Given the widely acknowledged limitations of present-day international global governance, the broader international community might be triggered to develop a number of complementary mechanisms to deal with this. Could it, for instance, be conceivable that some of them would organize a global solutions network, around great power assertiveness that would “clinically” monitor behavior, dissect rhetoric, “target” silent majorities, and identify possible ways out of impasses? Defense and security organizations—perhaps especially in small- and medium-sized countries—might be able to play a catalytic role in this development as the responsible custodians of the broader defense and security ecosystem.

Conclusions

We once again—against widespread prior expectations—find ourselves in an age of great power assertiveness, in which Russia plays an important role. Our empirical and theoretical knowledge about this type of international behavior and the geodynamics that surround it remains disappointingly limited. Current-day Russia, which in its previous incarnation as the Soviet Union was one of the most intensely and thoroughly investigated subjects in the international arena, is no exception to this unfortunate state of affairs. The country’s behavior keeps surprising the international community and there is little evidence that we have made any real progress on this score.

Our decidedly suboptimal understanding of Russia as a society, as a polity, as an economy, and as an international actor is further exacerbated by the quite idiosyncratic way in which “foreign and security policy analysis” is conducted—certainly when compared to other more mainstream forms of public policy analysis. The very basic common-sense precepts of this discipline are routinely flaunted and/or ignored in the field of foreign policy analysis. That is certainly the case with respect to the careful systematic collection of empirical evidence, but also to the modeling, option and criteria generation, trade-off adjudication, and communication efforts that build on it.

This nefarious combination of suboptimal situational awareness/understanding and underdeveloped policy analysis mechanisms bodes ill for policy-making. And yet, there are some encouraging developments as well. New scientific/technological developments—primarily in the fields of natural language processing, natural language understanding, and machine learning—offer unprecedented promise on both fronts. This memo illustrates some of the new insights that one (early) example of this technological confluence—event datasets—is likely to bring to field studies.

Truly new approaches to (also Russian) security policy analysis are sorely needed. Suggested here are three of these.

-

- Construct a more granular evidence- and knowledge-base for the various manifestations of Russian foreign and security policy thinking and acting, as well as for other actors’ thoughts and behaviors. Without this, any real analysis of the complex underlying dynamics will be impossible.

-

- Better align foreign and security policy analysis with the more mainstream (public) policy analysis field.

-

- Broaden our scientific aperture toward more synoptic analyses that also try to learn from other fields—both in terms of phenomenological analysis of what is happening and how to understand it but also of what it means for our policy options.

By Stephan De Spiegeleire, Khrystyna Holynska, and Yevhen Sapolovych with support from Yar Batoh, Daria Goriacheva, and Anastasiia Shchepina, The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies and Kyiv School of Economics (StratBase).

Note: The HCSS-Georgia Tech RuBase team is available to engage with colleagues who are interested in exploring the promise and peril of data-intensive science for the analysis of Russian foreign and security policy.

Acknowledgement: The authors and their colleagues gratefully acknowledge the financial support of Carnegie Corporation of New York (Project RuBase, 2018-19) and of the Dutch Ministries of Defense and Foreign Affairs (Strategic Monitor 2014-17, Progress Call 2018-19).

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this Policy Memo are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any other agency, organization, employer, or company.

[PDF]

[1] Despite this underlying similarity, they still differ so we filtered out only those patterns or trends that seem robust across most of these datasets. For instance, they all use (quite) different sources, coders, dictionaries, deduplication methods, etc. For more, see Holynska et al., “Events Datasets and Strategic Monitoring,” The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies (forthcoming).

[2] Philip A. Schrodt, “CAMEO: Conflict and Mediation Event Observations Event and Actor Codebook,” Event Data Project, Department of Political Science, Pennsylvania State University, 2012.

[3] TERRIER (Temporally Extended, Regular, Reproducible International Event Records) is a machine-coded event dataset built on all news reports available in the Lexis-Nexis data service from 1980 to 2015 and produced by a team at the University of Oklahoma as part of the NSF RIDIR grant “Modernizing Political Event Data” SBE-SMA-1539302.

[4] The “negative” type of assertiveness is based on the so-called “quad score” used in the CAMEO ontology (Schrodt, “CAMEO.”) which identifies every event in a binary way as either conflictual or cooperative as well as either factual or verbal.

[5] This normalization is required in light of the greatly increased number of publications that are covered in—especially—a dataset like GDELT.

Appendix: What Do the Event Data Not (Yet) Say?

Having illustrated some of the findings the event datasets can already provide us with, it is also important to highlight the limits of what we are currently able to achieve. First, these datasets’ quality needs to be further improved. Current funding levels coupled with the vertiginous breakthroughs in NLP/NLU seem to guarantee that their quality will continue to increase significantly. It remains an open question whether region- and/or domain-specific human, automated, and mixed coding efforts will allow us to improve the quality of the “generalist” NLP-coders. HCSS and Georgia Tech have obtained funding for at least the next three years to further explore this avenue—especially for Russia. Various other analogous large-scale research projects are also underway along similar lines.

Secondly, event datasets do not help us in absorbing and making sense of one of the richest datasets: (academic, more broadly scholarly, policy, etc.) text-based documents. Event extraction is only one of the many forms of semantic entity and relationship extraction that are mushrooming in the fields of NLP/NLU. Here too, region-/domain- specific efforts will be required, including in the field of Russian foreign and security policy analysis. Creating and validating ‘gold corpora’ models, on which machine learning can be trained, is an extremely labor-intensive effort that is now only getting off the ground in our area. To be successful, this will require novel forms of collaboration from a field that is bibliometrically demonstrably quite uncooperative.

Thirdly and most importantly, the major challenge will then be to store and curate all of that generated and extracted data, information and knowledge in “live” knowledge-bases—and increasingly knowledge graphs—that will finally offer us a chance to start both deductively identifying and testing (much broader) hypotheses across much richer empirical and semantic-conceptual datasets, but also to start inductively detecting possible robust patterns and trends that require further investigation. Most of us realize that, in “International Relations Theory” terms, both first- (individual, e.g., Putin), second- (societal and domestic-political), and third- (systemic but also geodynamic) level variables matter to Russian security policy and that to truly understand the way in which these intersect to produce Russian international behavior will require a different research approach from the one we have pursuing for (at least) the past few decades.

The bad news here is that our empirical and theoretical knowledge about great power assertiveness remains limited. Foreign and security policy analysis remains quite far removed from mainstream policy analysis which puts systematic evidence center front. The good news is that help is on the way in the form of rapid developments in natural language processing/understanding and machine learning tools that will start generating more and better policy-relevant evidence and knowledge.

Memo #: 636

Series: 2