(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) After first exploding among people who inject drugs in the late 1990s, HIV/AIDS now presents a serious public health and social challenge in Russia. The threat was initially mitigated through energetic interventions from civil society, largely financed by the global health community, that attempted to introduce best-practice prevention and treatment strategies. President Vladimir Putin’s third term and the consequent dismantling of most international partnerships coincided with a re-acceleration of the epidemic. Aggressive messaging touting the immorality of drug use and sexual activity/identity outside traditional norms has served as a potent tool in the Kremlin’s campaign to stoke scorn and fear of Western ideas and behaviors. One manifestation of this strategy: a blunt refusal to promote needle and syringe exchange, opioid agonist therapy (such as methadone), and even condom use, all key elements of the “harm reduction” approach universally acknowledged as an essential tool to prevent new HIV infections. Absent a wholesale shift in attitude and tactics, the Russian government will continue to confront a costly and expanding HIV/AIDS burden, an embarrassment to its aspirations for global power status.

The Epidemic

Russia’s official HIV tally crossed the one million mark in 2015. As of June 2018, almost 1.3 million people had been infected, 294,000 of whom have died. Over one percent of the overall adult population is HIV-positive, including 3.3 percent of men ages 35-39. Key populations—those most at risk, especially people who inject drugs (PWID), men who have sex with men, and sex workers—have prevalence rates considerably higher; estimates for the 1.5–2 million Russian PWID range from 18-43 percent. HIV/AIDS is now a leading cause of premature mortality: almost 16,000 Russians died of HIV/AIDS in the first half of 2018. The virus has skyrocketed from the 46th-ranked cause of lost life-years in 1990 to the 10th in 2016, passing every cancer except lung and all other infectious disease.

The Urals and Siberia disproportionately bear the burden. Kemerovo, Sverdlovsk, Tomsk, Irkutsk, Novosibirsk, Sverdlovsk, Chelyabinsk, Perm, and Krasnoyarsk currently have the highest infection rates, and most regions in the North Caucasus the lowest. The number of regions with prevalence over 0.5 percent increased from 22 in 2014 to 34 in 2018, with those 34 containing over half the country’s population.

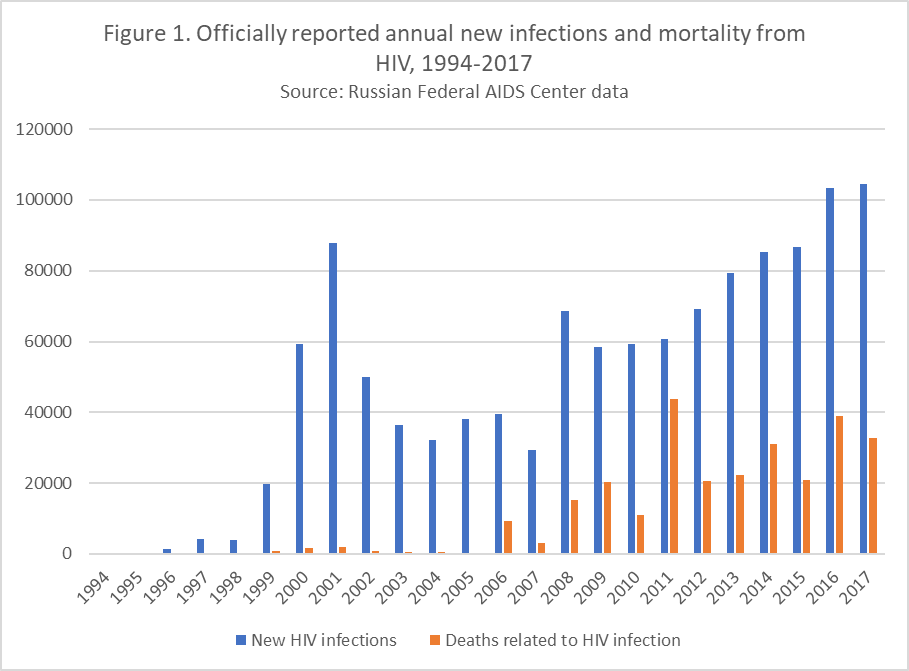

HIV/AIDS first appeared in Russia in the late 1980s. The numbers were relatively small until the use of injection drugs—largely fueled by the emergence of drug trafficking between Central Asia/Afghanistan and Europe—then soared over the following decade. Figure 1 illustrates the rapid increase in new infections from 1999 through 2001, virtually all transmitted through the sharing of drugs and non-sterile injection equipment. The strong intertwining of addiction, HIV, tuberculosis, and hepatitis C that developed early on led to characterization of the situation as syndemic.

The rate of new infection picked up again in 2008, likely due to the appearance then of alternatives to heroin in the Russian market: “synthetics” or “salts,” which are considerably less expensive and widely available over the internet. These drugs, at least initially, were less toxic, reducing the fear of overdose and increasing injection frequency. And for the last six years, in contrast to virtually everywhere else in the world where the epidemic has been receding, Eastern Europe’s—driven almost entirely by Russia—is growing.

The transmission vector for reported cases in Russia has shifted dramatically. The epidemic now features increasing heterosexual transmission, with more and more new cases in women. Among people under 30, new infection rates for women have begun to outpace those among men. It is likely that most of these women are the sex partners of infected drug users. Without effective intervention, this dynamic has the potential to shift the epidemic from key populations into the general population, increasing the likelihood of its further acceleration.

All these data reflect the numbers officially reported, capturing only people who have come in for testing and treatment. The real picture is harder to discern. In 2013, the Federal AIDS Center estimated that only around half of people living with the virus had been diagnosed. Stigma, discrimination, and criminalization of drug use, sex work, and sexual minority status form strong disincentives to engage with government testing centers and registries.

The Government Response

The Russian national HIV strategy for 2017-2020 explicitly calls for prevention programs to reduce the spread of infection, as well as treatment to reduce mortality. While this sounds reasonable in principle, the details matter. Although the “rehabilitation, social adaptation, and social support” of key populations is mentioned in passing, the document provides for neither resources nor road map to reach the people who need help the most. Instead, the focus falls on “rejuvenating the moral values of the nation” to combat the epidemic. And, in contrast to the 90:90:90 United Nations targets for 2020—diagnosis of 90 percent of HIV-positive people, 90 percent of those put on life-saving anti-retroviral therapy (ART), and 90 percent of those achieving an undetectable viral load—Russia’s strategy aims only for 60:60:60. Overall, the bulk of spending covers prevention of mother-to-child transmission during pregnancy (where the success rate has been high, around 98 percent) and plenty of mass HIV testing, but little to target specific vulnerable groups other than exhortation to avoid bad habits and immoral behavior.

Institutional inefficiency and infighting also hamper government efforts. Siloed agencies, a legacy of the Soviet era, prevent integration of care for PWID, people living with HIV, and those with other frequently related infectious diseases (tuberculosis, hepatitis C). An ongoing turf war between the Ministry of Health (responsible for treatment) and the Federal AIDS Center (part of the consumer rights protection service, responsible for surveillance and prevention) leaves the already-meager prevention budget vulnerable to cuts. Patients’ needs are often “left in a void” outside the direct responsibility and attention of state agencies, and civil society lacks the resources and authority to fill the gap.

Government agencies offer HIV testing and ART, available (in principle) free of charge at regional AIDS centers. The Health Ministry launched a federal registry in 2017 to make sure that HIV and tuberculosis patients could receive this treatment even outside their official place of residence. But in 2017, the Health Ministry spent $296 million on treatment that covered 235,000 people; that is only a fraction of those living with the virus. The Ministry of Finance axed a proposed allocation of $1.2 billion for 2018-2021 to combat the epidemic. AIDS centers face frequent stockouts, forcing patients to band together, frequently through internet chat rooms, to self-organize supply and redistribution networks akin to the Dallas Buyers Club. And the treatment that is offered is not the best available. Only 1.4 percent of Russian ART patients in 2018 received the most advanced “one pill a day” regimen, making adherence more complex, although the Health Ministry has adjusted its purchasing annually in recent years in favor of drugs with fewer side effects and higher efficacy. Antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)—starting ART in vulnerable people prior to possible infection—has, in other settings, prevented HIV transmission within serodiscordant heterosexual couples as well as HIV acquisition among PWID and MSM. But PrEP is currently not available in Russia.

The importance of primary prevention of HIV infection before it occurs, through education, behavior change, and harm reduction, is obvious. While officially sanctioned prevention efforts are almost non-existent in Russia, there are some notable exceptions. A national #STOPHIVAIDS (стопвичспид.рф) week happens every May, engaging celebrities, athletes, and religious leaders and is spearheaded by Svetlana Medvedeva, the prime minister’s wife. In Kazan, aggressive needle and syringe exchange programs brought the rate of new HIV infections down by 85 percent between 2001 and 2008, before national policy shifts forced the closure of seven out the city’s eight service centers. Still, Tatarstan has put more people on treatment than any other region—62 percent—and continues to hold high-profile awareness events, including a marathon in 2016 where the president, Rustam Minnikhanov, was publicly tested. St. Petersburg’s infection rates have declined recently as the city government countered national policy with continued international partnerships and effective outreach to PWID and sex workers.

But overall, members of risk groups are reluctant to intersect with government authorities, fearing abuse or arrest. A 2016 study of HIV-positive Russian women who inject drugs, for example, reported that almost a quarter had been forced at some point to have sex with a police officer. This mistrust of authority is not unique to Russia. Worldwide, it is what makes non-governmental actors—peer groups who can link effectively with people most at risk—the cornerstone of HIV prevention.

The NGOs

The government has not completely shunned HIV/AIDS NGOs. The Russian Orthodox Church has been generous in its provision of palliative care to people dying of AIDS, and quite a few civil society organizations have received presidential grants to deliver medical, psychological, social, and legal support for those seriously ill. But official hostility to Western ideas and connections, drug users, the LGBTQ community, and civil society in general has made AIDS officials highly reluctant to support NGOs delivering prevention services.

At their peak in the early 2000s, there were hundreds of national and local NGOs filling the vacuum left by government mistrust and neglect. Their outreach to vulnerable population groups certainly contributed to the receding of the epidemic at that time. In 2012, however, the notorious “foreign agent” law knocked many organizations supporting drug users, sex workers, and LGBTQ rights groups out of commission, forcing them to close or scale back their efforts. Even the NGOs that tried to stand firm found themselves subject to “death by government inspection” and had no choice but to divert scarce resources to lawyers and accountants instead of on actual mission. Further blows were struck by the 2013 law criminalizing the dissemination of information about same-sex relationships to minors (spearheaded by the Orthodox Church). And Putin’s re-ascension to the Russian presidency swiftly took most international support, both financial and technical, off the table. The United States Agency for International Development was expelled in 2012. The last grant from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria closed in 2017, but disbursement had slowed to a trickle starting in 2013. Some committed, skilled civil society professionals have stayed in the fight, but many more have understandably left for the private sector or abroad. As a result, only 20 active needle and syringe exchange programs remain.

The Need for Harm Reduction

The only way to stop this epidemic is to reach key populations with education and services that prevent transmission. In Russia, that approach would start with humane treatment of addiction. Instead, Russian official policy handles drug use as a criminal justice rather than public health matter, producing scorn and discrimination against PWID. The “science” of Russian narcology is, in practice, not scientific at all. A 2013 law introduced compulsory treatment, ostensibly to motivate addicts toward rehabilitation. But what they get instead is a range of ideologically-driven, unproven, potentially life-threatening practices including chaining patients to beds, shock therapy, coma induction, and heating patients’ bodies to 43 degrees Celsius. Not surprisingly, only about 2 percent of Russians convicted of drug offenses choose treatment over punishment, and only 1 percent of people ordered involuntarily into “treatment” have remained drug-free a year later. Human rights organizations, including committees of the United Nations, have classified these tactics as human rights abuses; one highly respected Moscow-based service provider calls them “torture and cruelty.” The declining number of narcologists in the country suggests growing discomfort among physicians and scientists with the questionable professional ethics around implementation of these unsound government policies.

International best practice offers opioid agonist therapy (OAT) to addicts, but Russia is staunchly and stubbornly opposed. Government officials at all levels parrot the party line on methadone and buprenorphine (which are proven to reduce cravings, prevent withdrawal symptoms, and enable addicts to stabilize their lives), saying that the legalization of these drugs would serve the interests only of the international pharmaceutical industry, replacing one addiction with another, and creating new black markets. Tereza Kasaeva, a former deputy health minister in charge of HIV/AIDS (now head of the World Health Organization’s Global Tuberculosis Program), has said that harm reduction “looks so smart” but “doesn’t solve the problem” because it focuses on the symptoms rather than the underlying causes of addiction. Viktor Ivanov, former head of the Federal Drug Control Service, has called OAT a “murderous therapy” that “chains its prisoners to their own chemical handcuffs.” The impact of the ban on OAT was immediately and starkly felt in Crimea, where the 2014 occupation abruptly cut off services to nearly a thousand drug users. United Nations data indicate that at least 120 of those patients have died from suicide, overdose, or complications from HIV and tuberculosis, a fate they most likely would have avoided had their medication been continued.

As for sexual transmission of the virus, public education campaigns promoting condom use are few and far between. There are enormous legal boundaries around sex education for adolescents and teens, with the approved curriculum stressing abstinence and moral character. The private sector has entered the conversation to a limited degree; Durex condoms, for example, are advertised on television with a nod to HIV prevention. But the government lands on the side of silence, with Deputy Health Minister Sergei Krayevoi noting that “a genuinely free society should be about respecting the cultural and religious traditions of a nation.” A nationwide webinar sponsored by the Education and Science Ministry for World AIDS Day in December 2017 pointedly asked lecturers to avoid using the word “preservativ” (condom), prodding them instead to focus on virtue and traditional values.

The Path Forward

Russia’s HIV/AIDS epidemic is not just a humanitarian concern. The financial and social costs, particularly if the disease continues to spread beyond stigmatized risk groups, could fuel political and economic instability. Inconsistent adherence to ART can breed treatment-resistant virus, with the potential for spread beyond Russia’s borders. And perhaps most importantly, the domestic NGOs that persist in the fight against the epidemic—and against their own government’s backwardness—are deserving of continued recognition and whatever support can be mustered. The bottom line is that the current epidemiological and medical situation is completely avoidable. It is driven by state policy hostile to ideas from the West, effectively turning public health into just another weapon in the Kremlin’s anti-Western propaganda arsenal. Given abundant scientific evidence and clear precedent set by many other countries, it is reversible. Only politics and ideology stand in the way.

Judyth Twigg is Professor in the Department of Political Science at Virginia Commonwealth University.

[PDF]