(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) The COVID-19 pandemic hit Russia at a precarious moment marked by a global oil war and constitutional reforms intended to secure regime stability beyond 2024. These three crises place significant pressure on the Putin system defined by its focus on statism, international standing, and a power vertical that concentrates power within the national government. As in other federal systems, the Kremlin has responded to the challenge by outlining a decentralized response, resulting in a scramble in the central and regional governments to limit costs and evade blame. In this memo, we demonstrate the variation in regional threats and regions’ capacity to meet these threats, then assess the potential effects of de facto decentralization. This analysis demonstrates a mismatch between the nature of the threat and the regional resources available to meet the crisis and points to the likelihood that regional policy will vary in response to the trade-off between public health and economic costs.

Central Government Response: Decentralization and Blame Shift

The government’s initial response to the virus increased autonomy for regional governors. Given the differences in geography, urbanization, and economic foundations that condition the spread of and capacity to respond to the virus, each region requires unique solutions. Regions also have variations in their capacities to implement responses ordered from the center. These differences shape compliance with central orders and regional innovation in policy responses.

Many Russia-watchers have observed that decentralization may be part of a strategy to shift blame for the central government’s response onto regions. President Vladimir Putin signaled this strategy in his April 8 meeting with governors, saying, “I believe you understand how much personal responsibility you have for ensuring that the allocated funds are used as effectively as possible.” Putin’s references to “criminal negligence” during the April 13 meeting on the spread of COVID-19 are also indicative of his intent to shift blame to regional actors. Decentralization in the midst of crises is not unique to Russia. While macroeconomic crises often result in recentralization, crises in governability—such as COVID-19—often generate decentralization as the center attempts to shift the costs, and potentially blame, for tough or unpopular measures onto local officials.

The critical difference in the ongoing crisis is how the current decentralization of authority to make policy compares to the decentralized implementation of central mandates in the power vertical. The latter mode of decentralization discouraged local initiative and fostered obedience, discipline, and loyalty in regional leaders. It also shaped Russia’s current healthcare system. Russian regional authorities are primarily responsible for the design, funding, and administration of public health in response to Putin’s 2012 May decrees. These decrees mandated “optimization” of the healthcare system by closing local clinics, merging hospitals, and cutting staff, all of which strained the public healthcare system. Poised to take on the rapidly developing COVID-19 crisis, regional governors now face disgruntled doctors, underpaid nurses, and medical support staff who spent much of 2019 protesting optimization decisions. As we show below, not all governors have the resources or leadership essential for navigating this crisis.

Regional Differentiation: The Nature of the Threat and Demands to Respond

A central focus at all levels of government is the challenge of managing the preservation of economic and social production while limiting the effects of the virus. Different Russian agencies are tracking the virus’ spread, and their efforts show considerable variation. Novosibirsk-based 2GIS created a website that maps official Rospotrebnadzor data on cases, hospitalization, and deaths. Similarly, Russian Internet company Yandex is mapping cases and compliance with isolation orders based on traffic flows. These sources show that Moscow remains the center of the pandemic with St. Petersburg seeing increasing cases. Clusters are also emerging across the Federation in the regions and are spreading within federal districts in waves.

Figure 1. Pensioner Prevalence and Availability of Doctors

Regional governments acknowledge the trade-off between economic activities and anti- COVID-19 measures. While many economists agree that Russia is well-positioned to manage the pandemic’s economic fallout and falling oil prices, the effects will vary across regions depending on the threat and capacity to treat the virus. In Figure 1, we demonstrate the relationship between the 2017 pensioner population (measuring regional vulnerability to the virus) and the 2019 availability of doctors (measuring regional capacity to respond). The figure shows that there is a trade-off for some regions based on these factors with the highest threat in the upper right quadrant.

In an article, Meduza uses open-source data to demonstrate that the availability of ventilators also varies regionally. There is considerable overlap between regions with high pensioner populations and low ventilator and doctor availability. At the same time, new data demonstrate that the magnitude of the crisis might be greater in small cities and rural areas as resources are concentrated in large urban areas.

Driven by this variation, three distinctions are emerging across regional responses to COVID-19 as governors respond to opportunities to innovate and provide effective leadership. The first distinction is embodied by the timing and level of self-isolation and subsequent decision to relax restrictions. Only 14 regions adopted strict self-isolation practices such as domestic travel prohibitions and shuttered public transportation services, according to Vedomosti on April 7. Other regions quickly relaxed regulations or opted against enforcing them, ended self-isolation early, or expanded the list of essential enterprises. As we reiterate below, tracking the effects of these decisions going forward provides a complex but critical research program to understand the economic cost of the pandemic in Russia.

The second focus of regional response centers on support for vulnerable citizens. Regional governors will have to engage with the public, grassroots organizations, and potential collective action on the part of the groups most affected by the crisis, especially politically engaged pensioners. Certain activist governors are already using their autonomy to insulate themselves against shifts in popular opinion. Veterans and the elderly have been the subject of special attention as programs emerge to deliver food, medical supplies, and health information in Samara, Ulyanovsk, Moscow, and St. Petersburg—a trend that is probably more widespread. In some regions, both United Russia and the All-Union People’s Front are organizing these efforts. Notably, Primorsky Krai announced a jobs program for the unemployed. Given concerns about unemployment on social media, we expect these programs to become more common.

In addition, most activist governors are supporting private enterprise and SMEs through tax deferments, loans, and other supports. On April 8, Putin ordered the government to develop a national business support scheme, as business associations continued to press for state support. He also offered tax deferrals to small- and medium-sized enterprises for the next six months; they can now be repaid in installments over time. The most activist of the governors are amplifying these programs, although many are constrained by resources or capacity. Gleb Nikitin, governor of Nizhny Novgorod, advanced innovative solutions to support restaurants, hotels, and transport companies in the city by contracting with them to provide housing, food, and transport to medical workers concerned about endangering their families.

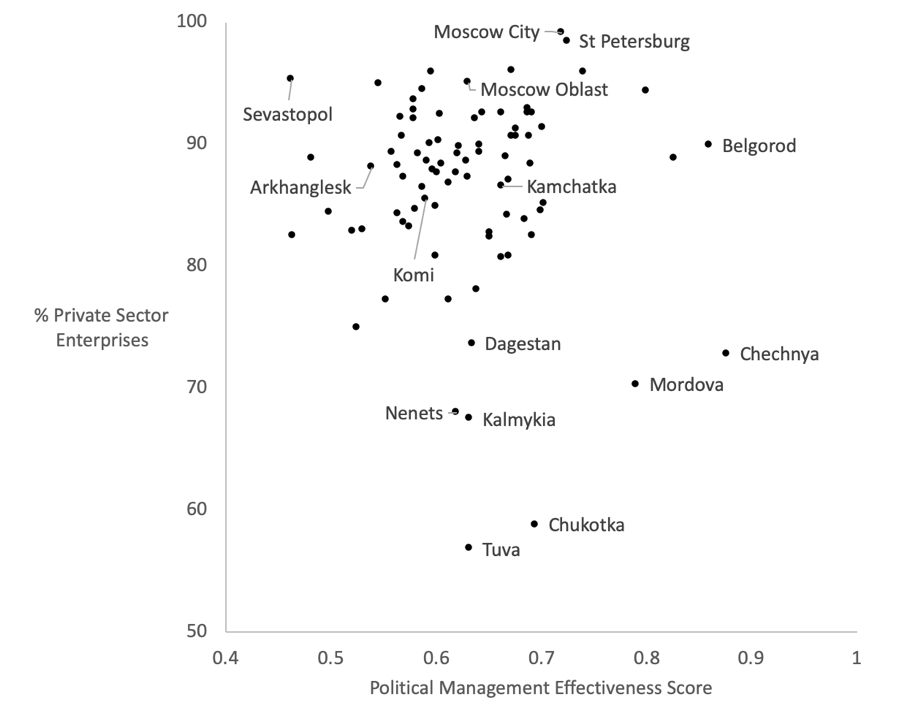

Figure 2. Regional Leaders’ Economic Risks and Capacity to Handle Them

Figure 2 illustrates the trade-offs that regional leaders face in terms of economic risks and the capacity to meet them. The 2018 measure of private enterprises does not capture employment figures for each type of enterprise, but it does show the difference in potential dislocation—unemployment and lost revenue—in different regions. The March 2020 effectiveness score captures gubernatorial resources: popular support, elite unity, and ties to the center. The figure underscores trade-offs between regional challenges and governors’ capacities to respond, and identifies vulnerable leaders.

These factors come together when we consider longer-term trade-offs between the restrictive measures aimed at stopping the spread of COVID-19 and the measures that mitigate the economic and social fall-out at the regional and national levels. At a March 30 meeting with presidential envoys in the federal districts, Putin asked the regions to prepare lists of vital enterprises. These enterprises will maintain operations to ensure employment and social stability. They are also more likely to be sustained by governmental support through subsidized credits, investment plans, and other types of assistance.

Although the governors have more responsibility, the federal “leash” is still in place. At the April 8 meeting with regional leaders, Putin criticized regions such as Karelia where the authorities closed most enterprises. He instructed governors to prepare for a gradual return to normal economic activity. Governors in the Far Eastern Federal District—Amur and Khabarovsk—responded quickly, and many businesses and government service centers reopened a few days later. In Saiansk, a city in Irkutsk oblast, Mayor Oleg Borovsky re-opened the city’s service industry on April 3, prompting the city procuracy to contest his decision because it contravened the presidential order. Borovsky received nationwide recognition as a defender of business after being interviewed on Channel 1.

In contrast, Primorsky Krai, Sakhalin, and Sakha maintained and even strengthened restrictions. Moscow Mayor Sobyanin also tightened restrictions, introducing a system of electronic passes for residents; such passes were adopted earlier in the Republic of Tatarstan and Nizhny Novgorod.

The Blame Game and the Potential Rise of New Leadership?

Since the early 2000s, “if not Putin, then who” has been the slogan of Russian elections, signaling the lack of credible alternative candidates and resigning Russians to the choice of “stability” embodied in this singular choice. A key element of this “if not Putin” strategy has been the elimination of a meritocratic ladder of political ambition that allows competent and popular leaders at lower levels of government to rise to power. As part of this process, many incumbent governors (some considered as regional heavyweights) have been replaced with technocrats and managers who focus on efficiency and policy implementation rather than politics. Charismatic regional and city leaders are quickly eliminated.

Nonetheless, the Levada Center reports that on average regional governors are as popular as Putin, although individual governors’ ratings vary. Popularity will be a factor in the blame game, as the toll of the virus and its economic costs mount. Governors unable to maintain social stability in their regions are likely to be dismissed. The Kremlin’s first actions removed three unpopular governors in Komi, Arkhangelsk, and Kamchatka. These regions are also some of the most vulnerable, as depicted in the figures above. For governors, loyalty and effectiveness is a mixed blessing. The successful governor of Nenets autonomous oblast took the helm of Arkhangelsk.

This strategy of devolution in response to COVID-19 and the Kremlin’s early response undercuts the present model of personalist leadership in Russia. For a brief period, Putin was largely absent and appeared irrelevant despite television appearances promising mortgage and loan repayment extensions, meeting with health officials, and providing directives to regional officials. As Vladimir Gel’man argues, this may be a strategy to evade blame for outcomes of the virus, but many observers have speculated about longer-term reputational effects.

This dynamic played out as Putin appointed Sobyanin to chair the pandemic’s National Task Force. As a former governor of the Tyumen region, Sobyanin recognizes the regional factors in crisis decision-making, but as Figure 2 illustrates, he also faces significant challenges in pulling Moscow through the challenge. Sobyanin, and not Putin, ordered many of the significant restrictions on social interaction and economic activity to slow the spread of the virus. In doing so, Sobyanin assumed his place as a national leader and solidified his position as the presumptive second in command, but he is also vulnerable to blame-shifting. It remains to be seen if these strategies insulate the president and his government or exacerbate the decline in popular trust in government and leadership that has intensified over the past year.

Conclusion

In the face of the pandemic, the Kremlin faces a whirlwind of systemic pressures that are likely to grow in the coming months. The government undoubtedly will leverage its economic, institutional, and media resources to stabilize the system. Anti-crisis measures are likely to reinforce the social agenda Putin announced in his January 2020 annual address to the Federal Assembly. Limited measures mitigating social crisis and a stimulus package following Western examples are being crafted now. Anticipating 2021 parliamentary elections, the Russian parliament and United Russia are also now engaged in developing this policy response.

By the time Russia re-emerges from the crisis, however, the foundation of the system might be significantly different, although the overall framework could look the same. The effects of the pandemic and the ensuing economic crisis are revealing the social and economic vulnerability of the population and the hollowness of the regime’s achievements (which were declared by Putin in his 2020 address to the Federal Assembly.) The level and form of new crisis-related information and its effect on popular attitudes will vary across Russia and will be dependent on regional governments’ responses and grassroots efforts that shape the economic and social impacts of the virus. The confluence of political, economic, and healthcare crises will almost certainly amplify trends of increased distrust in government institutions and central leadership. The regional variation in these trends and the effectiveness of governors’ policies in response to mounting problems will define the extent of the challenge to the regime.

Regina Smyth is a Professor of Political Science and Faculty Affiliate of the Russian and East European Center and the Ostrom Workshop at Indiana University.

Gulnaz Sharafutdinova is Reader at King’s Russia Institute in the School of Politics & Economics at King’s College London.

Timothy Model is a Post-doctoral Fellow at the Havighurst Center for Russian and Post-Soviet Studies at the Miami University, Ohio.

Aiden Klein is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science and a Fellow at the Ostrom Workshop at Indiana University.

[PDF]

Homepage image credit.