(PONARS Policy Memo) Since independence, politics in Ukraine has often turned on issues of identity. Ethnic and linguistic cleavages have tended to underlie political divisions and have been used by politicians to avoid responsibility for corruption, economic and social decline. However, twice in the post-Soviet era, during the Orange revolution of 2004 and the Euromaidan revolution of 2013-14, Ukrainians from across the country came together to push for revolutionary change and a new dawn for the Ukrainian state. Such revolutionary events are often the source of new identities, and both revolutions were hailed as moments that would unite Ukraine as never before.

In this memo, we present some findings about how these massive political shocks have affected the evolution of ethno-linguistic and national identities by analyzing public opinion surveys from before and after the two revolutions. We find that despite differences in the nature of the two revolutions, the effects have largely been similar. At the aggregate level, patterns of ethnic identification and language use are largely unchanged. By contrast, both revolutions led to a significant increase in civic identification with Ukraine as a state. In each case, initial surges of civic nationalism declined somewhat, but both revolutions left more people in the country thinking of Ukraine as their homeland than before. In this sense, revolutions appear to have played an important role in state consolidation in post-independence Ukraine.

Revolution and Identity in Ukraine

Scholars have long recognized that large-scale political changes like revolutions are likely to have important effects on the identities of the people affected. In fact, revolutions, particularly in the post-Soviet space, have often been launched explicitly as identity-changing projects, whether it was the creation of a Homo Sovieticus or the construction of new pluri-ethnic conceptions of identity in the newly independent former Soviet states like Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, or, for that matter, Ukraine. In this sense, the Orange and Euromaidan revolutions were no exception, with supporters hopeful that the overthrow of corrupt and divisive incumbents would lead to a new sense of unity amongst Ukrainians of different ethnicities, languages, and regions. Nevertheless, as is so often the case, the implications of each revolution for identity would, on the face of it, seem contradictory.

On the one hand, we might have expected both the Orange and Euromaidan revolutions to prove divisive in terms of identity. After all, both revolutions appeared to pit a more Ukrainian-speaking west and center against a south and east that was predominantly Russophone and had higher shares of ethnic Russians, and both conflicts ended with a victory of the “Ukrainian” over the “Russian” side. Moreover, in both instances, the domestic conflict was reinforced by external powers, with the revolutionaries receiving support from the West and the incumbent being backed by Russia.

On the other hand, despite this highly politicized ethno-linguistic cleavage, many of the protesters in the two revolutions were actually Russian-speakers (Beissinger 2013, Onuch 2014), which arguably mitigated the potential fallout in terms of ethno-linguistic conflict. In fact, both revolutions involved large-scale and sustained civic mobilization efforts across large swaths of the country and substantial proportions of the country’s overall population (especially in Kyiv and western Ukraine).

Despite these similarities, however, the two episodes also differed in ways that should affect their impact on identity in Ukraine. First, the Orange Revolution was remarkably peaceful and ended with a repeat of the contested presidential election. By contrast, the Euromaidan quickly degenerated into substantial violence, which in turn triggered a change in the composition of the protesters, with radical nationalists becoming more prominent as the violence escalated. Second, whereas in 2004-05 Russia grudgingly accepted the outcome of the Orange revolution, in 2014 it responded by force, first by annexing Crimea and then by providing economic and military support for separatist rebels in the Donbas. This loss of territory due to Russian intervention has led a number of observers to predict a significant “rallying-around-the-flag” effect (Alexseev 2015, Kulyk 2016), which may also reduce the appeal of a Russian ethnic and/or linguistic identity among Ukrainian citizens in government-controlled areas.

As a result, we might find a range of different effects of the revolutions on identities. To understand what actually took place, we looked at data from two sources. The first is a three-wave public opinion panel survey of Ukrainian residents, which we commissioned from the well-known Ukrainian survey research firm, Razumkov Centre. The first wave was fielded in December 2012, a year before the Euromaidan, while the two post-revolutionary surveys took place in June 2015 and July 2016. To ensure sample comparability our analysis below is based on the 674 respondents who were interviewed in all three waves and thus excludes respondents from areas currently not controlled by the Ukrainian government.[1] The second data source is a series of cross-sectional surveys from the Institute of Sociology, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. These Sociological Monitoring surveys included surveys from the years preceding the Orange revolution (2002, 2003, 2004) as well as from the post-revolutionary period (2005, 2006 and 2008.)

While the complicated and contested issue of how to measure identity in Ukraine is beyond the scope of this memo, we look at three different elements that tap into distinctive dimensions of national identity and linguistic practice in Ukraine, and for which we had comparable data over multiple years.

The first dimension of identity was based on a question that simply asked respondents what their nationality was, with options including Ukrainian, Russian and a number of smaller ethnic minority options. In using the term “nationality” (Russian: национальность; Ukrainian: національність), we adopted a standard term derived from Soviet nationalities policy that refers to national minorities—essentially officially recognized ethnic minorities. As expected, this indicator of ethnicity is correlated with home language use, but far from completely.

Our second dimension of identity is civic rather than ethnic and seeks to probe more directly the political nature of identity. In our surveys, we asked respondents to identify their homeland (Russian: родина; Ukrainian: батьківщина) with the main choices being Ukraine, the respondent’s home region, the USSR, and Russia. In the Monitoring surveys, respondents were asked what they most considered themselves as, with options including “Ukrainian citizen” as well as a variety of subnational and supra-national options (including USSR and regional level).

The third measure does not address identity directly, but rather focuses on linguistic practice. Language politics have been a key cleavage in Ukraine since independence (Arel and Khmelko 1996) and language practices (particularly outside of the west of the country) are famously flexible. While there are a number of different ways to address the language question, we focused on the concrete question of what language respondents use at home with options including primarily Ukrainian, primarily Russian, both Ukrainian and Russian, as well as a number of minority languages.

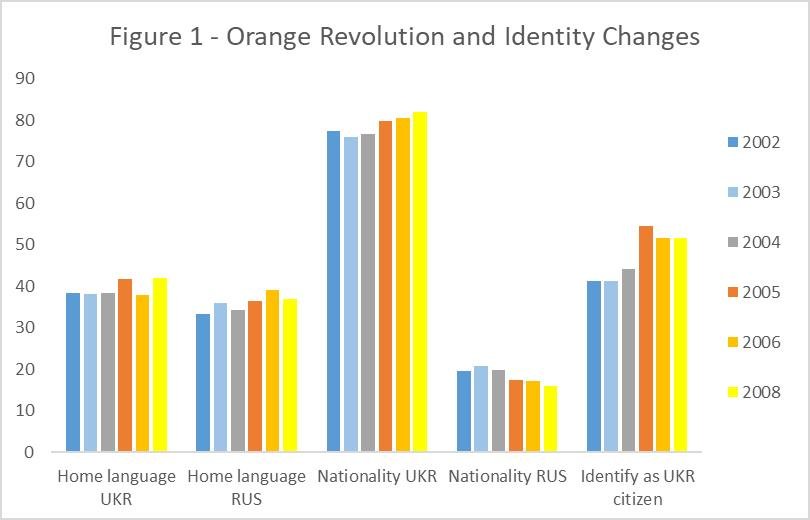

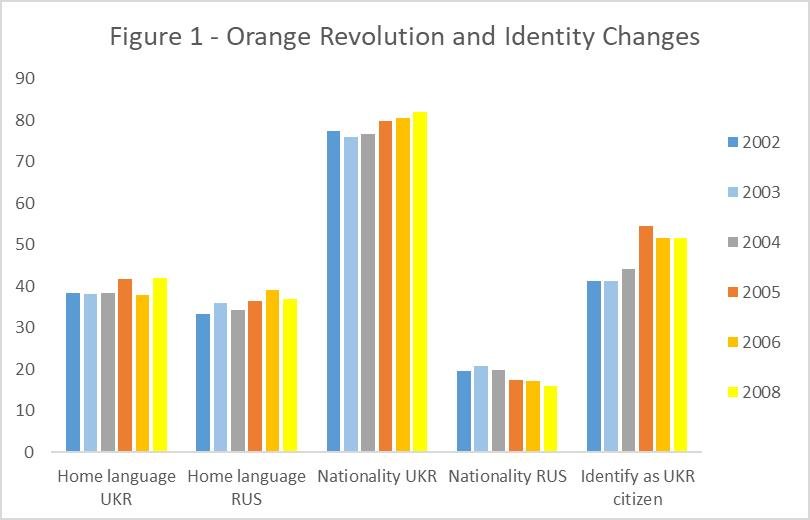

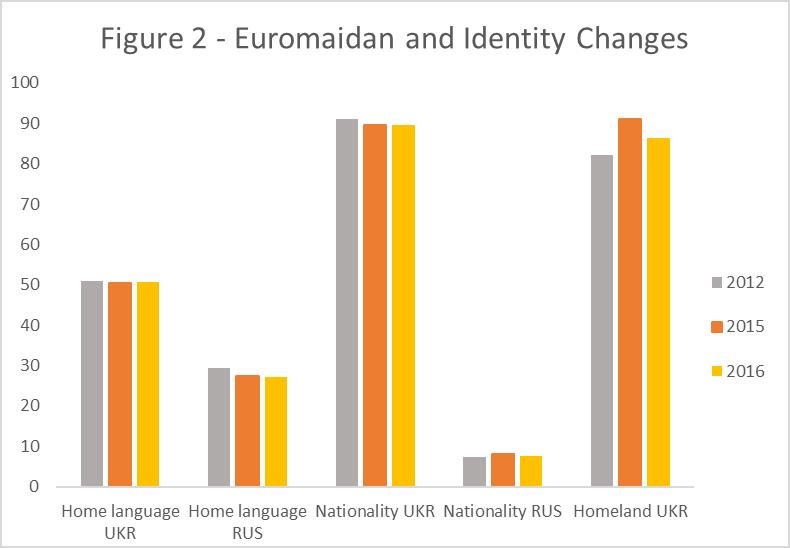

Figures 1 and 2 below illustrate the evolution of aggregate proportions in the three types of identity markers before and after the Orange Revolution and the Euromaidan.

Comparing the patterns in Figures 1 and 2, the only clear change in both revolutionary episodes is the increase in the civic identification with Ukraine: thus, the share of respondents identifying primarily as Ukrainian citizens increased from 44 percent in 2004 to almost 55 percent in 2005, while the share of respondents who identified Ukraine as their homeland rose from 82 percent in 2012 to 91 percent in 2015.[2]

Furthermore, even though in both cases this initial surge in civic nationalism was followed by a partial retrenchment, the identification with Ukraine stabilized at noticeably higher levels than before the two revolutions, thereby creating a ratcheting effect that points toward an increasingly universal embrace of Ukrainian statehood.[3] While seen in isolation the growing embrace of Ukrainian statehood from 2012-15 could be interpreted as a rallying-around-the-flag effect in response to the conflict with Russia, the presence in Figure 1 of a similarly sized effect in the wake of the Orange revolution suggests a different interpretation centered on the role of these civic mass mobilizations in cementing the civic identity around a Ukrainian statehood defined at least in part by the rejection of the creeping authoritarian retrenchment in many post-Soviet republics.

By comparison, Figures 1 and 2 reveal very limited evidence that either of the revolutions resulted in similar increases in either the embrace of Ukrainian nationality or the use of Ukrainian as a home language. With respect to nationality, the small shift from Russian to Ukrainian identification from 2004 to 2005 appears to have been part of a broader temporal trend that started before 2004 and continued after 2005, while for 2012-16 we find no discernible aggregate trends. Similarly, after 2004 both Ukrainian and Russian home use increased slightly (largely at the expense of respondents speaking both languages), while after the Euromaidan a slight decline in Russian home use did not translated in greater Ukrainian usage but instead bolstered the dual-language category.

While this aggregate stability in both nationality and home language use does not preclude significant individual or even local/regional ethno-linguistic identity changes,[4] it nevertheless suggests that the growing civic identification with Ukraine as a state was not accompanied by a growing ethno-linguistic dominance of Ukrainian over Russian identity. This interpretation is reinforced by some additional trends in public opinion in our 2012-15 panel surveys, which we analyze in depth in an article to be published next month in Post-Soviet Affairs: even though support for Russian as a state language declined (from 28 percent in 2012 to 23 percent in 2015), this trend was balanced by a significant drop (from 45 percent in 2012 to 29 percent in 2015) in the share of Ukrainian citizens who think that only Ukrainian should be used for local administrative use.

Despite some subsequent backsliding—the proportion of Ukrainians supporting Ukrainian as the only administrative language increased to 34 percent by 2016—these public opinion trends could form the basis of a civic nationalist project that adopts a multi-ethnic and multi-linguistic definition of Ukrainian nationhood in exchange for the support of ethnic and linguistic minorities for the fledgling Ukrainian state. However, this hopeful civic nationalism scenario currently faces considerable challenges both because the continuing corruption and slow pace of reforms undermine the crucial state-building project required for meaningful citizenship and because the inter-ethnic cooperation needed to achieve compromise on sensitive issues (such as language or education policies) is constantly challenged by radicals on both sides.

Conclusion

As Viktor Yanukovych fled in the dark of night to Russia, hopes were high that the Euromaidan Revolution would herald a new dawn for Ukraine. The wish list of changes was long and varied, but high on that list for some was a hope that this revolution would begin to reverse what they saw as the effects of centuries of Russification. In this memo, we presented some data focusing on what identity change has actually taken place since the Euromaidan.

The picture we have shown is mixed—a high degree of aggregate stability in terms of language practice and ethnic identification alongside a marked increase in civic identification with the Ukrainian state. Moreover, as we demonstrate, these patterns are largely the same as those changes that took place more than a decade ago, following the Orange Revolution. Placing the two revolutions together like this is fascinating. First, the comparison shows the power of these foundational moments in politics to shape identities in a lasting way going forward, even if the political effects of the revolution fade over time. Second, the comparison indicates something important for understanding what has changed and what has not over the course of Ukraine’s turbulent last decades—increasing acceptance and legitimacy for Ukraine as an independent state, but one that is–and likely will remain–multiethnic and multilingual in character.

Grigore Pop-Eleches is Professor in the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University.

Graeme Robertson is Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

[PDF]

[1] To deal with the potential problem of uneven attrition patterns we weighted our observations to account for the differences in panel attrition rates across different demographic groups.

[2] As mentioned, the shares are not directly comparable across the two periods both because of the differences in question wording and because Figure 2 is based on a sample that excludes Crimea and the Donbas. However, it is worth noting that we observe similar patterns when using the monitoring surveys for the years before and after the Euromaidan.

[3] Of course, this growing universality was at least partially due to the fact that the regions with the weakest allegiance to the Ukrainian state—the Donbas and particularly Crimea—were no longer represented among the respondents in Figure 2.

[4] Indeed, analysis of individual level data reveals substantial changes in ethnic identity and especially home language use but changes toward Ukrainian identity were as likely as changes away from Ukrainian, and therefore the overall population shares of different ethno-linguistic groups were largely unchanged. In separate work, we analyze the drivers of individual-level identity change, and find that individuals are more likely to change towards the ethnicity/linguistic practice of the group that is dominant at the local level.