(PONARS Policy Memo) For much of Vladimir Putin’s presidency, and especially since the 2011-12 Bolotnaya demonstrations, the Kremlin has claimed that Russia is threatened by internal enemies. Various actors have been singled out, including opposition activists, journalists, NGO representatives, and gay people. In many instances in which these groups are criticized, they are said to be sponsored by or doing the bidding of foreign—usually Western—governments. In other words, they are accused of being fifth columns. Fifth columns have a longstanding pedigree as the fixation of aggrieved rulers, who typically, but not exclusively, practice undemocratic politics. They seek legitimacy from posing as the defenders against scapegoats and external threats. In Russia and other post-Soviet countries, several factors favor political rhetoric about fifth columns: weak states, unconsolidated or absent democracy, corruption, disputed territorial claims, and contested geopolitical alignments. To date, there has been no systematic study of when, how, and why claims about fifth columns in the region are made.

In this memo, I report a first effort to collect and analyze claims about fifth column activity in the post-Soviet period. The data come from a larger project on conspiracy theories in the region, and cover a sampling of time periods associated with critical events from 1995 to 2014. I identify three types of claims that correspond to different threats and ascertain who makes allegations and under what circumstances. I show that they have increased over time and are invoked most often when rulers face visible challenges from below. People in Russia make the most claims, but more often about neighboring states than within Russia itself, reflecting (probably contrived) fears about Western meddling in the “near abroad.”

Taking the Fifth

Putin did not invent the idea of fifth columns. Although the term originates in the Spanish Civil War, historical episodes involving fifth columns emerged from the confluence of the collapse of empires and great power rivalries. Poorly assimilated or state-seeking minorities would solicit outside support for their cause, and external patrons obliged as a way to project power by acting from within the state.

The rhetorical template for today’s fifth column politics involving Russia and the United States arose during the Cold War. Then, it was not ethnic minorities but rather ideologically driven citizens who either acted as real fifth columns by spying on their country on behalf of the adversary, or were unfairly impugned as fifth columns due to their nonconforming beliefs. Red-baiting served electoral purposes for politicians in the United States, and the persecution of capitalist “wreckers” signaled the ideological fidelity of ambitious apparatchiks in the Soviet Union.

In the current political era, the notion of infiltration by fifth columns has been taken up with enthusiasm by populist leaders in democracies and autocracies alike. For example, in Turkey, President Recep Erdoğan has accused his political opposition, protesters, investors, and most recently civil servants, of working on behalf of Europe, the “interest rate lobby,” or exiled movement leader Fetullah Gülen. He escalated these claims at the same time as he weakened democratic institutions and amassed more power. In Hungary, Viktor Orbán has been vocal in implicating purported internal enemies and their backers, focusing his ire on nongovernmental organizations that advance democracy and European values; the influx of refugees from Muslim countries; and financier George Soros, who was the focus of Orbán’s successful 2018 campaign for parliament.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has been viewed as one of the most avid promoters of the threat of fifth columns, partly in response to the color revolutions on Russia’s borders, in which opposition leaders and NGOs received (some) Western support and training. Some analysts believe Putin pioneered the current populist wave, by showing how a politician can play on people’s insecurities to win support. Naming enemies was a critical feature of Russia’s democratic backsliding, especially with the advent of the so-called color revolutions. But did the Kremlin really initiate fifth column claims during this time, or were they a feature of Russian politics prior to 2004-5? And did Russia excel at fifth column claims, or were more precocious dictators even better at contriving enemies to consolidate power? Finally, are fifth column claims a natural feature of the political landscape, or are they precipitated by specific types of events?

Data and Analysis

To answer these questions, I draw from a dataset of conspiracy theories in the former Soviet Union. The data consist of conspiracy claims appearing between 1995 and 2014 in a sampling of Russian-language newspapers, Internet sites, wire services, and TV stations from the Integrum database. Conspiracy theories on any theme were collected one week before and one week after a sampling of 42 significant global or regional events such as elections, protests, terrorism, and other political developments. Searches were conducted using a set of Russian keywords often associated with conspiracies. When a conspiracy theory was found, the country where the conspiracy took place, and the identity and nationality of the accuser, perpetrator, the victim, and keywords were also recorded.

Approximately 17 percent of the 1,078 conspiracy theories in the dataset (as of September 2018) involve fifth columns, even though the term “fifth column” only appears 27 times. To be labeled as such, a claim must simultaneously implicate at least one actor inside and one actor outside the state, with the accusation that the latter is directly influencing the behavior of the former.

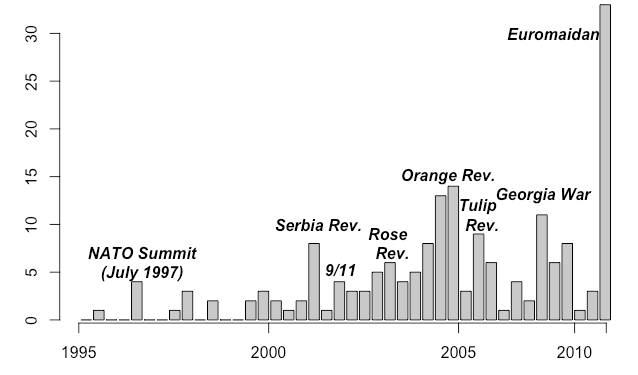

First, I ask whether they increase over time by looking for trends in two ways: counts associated with the 42 critical events, and instances in which the claim is unrelated to the event.[1] Using linear regression, by both measures, fifth column claims increase over time, though the trend is weaker when looking only at fifth column claims that appear in the dataset by chance. Figure 1 shows total claims over time corresponding to the 42 sample dates. Besides the Euromaidan (sampled from February 15 to March 1, 2014), the 2004 Orange Revolution and the 2008 Georgia War involved the greatest number. By contrast, the two weeks surrounding the failed Azerbaijan revolution (November 1-November 15, 2005), the Medvedev-Putin “tandem” announcement (December 3-December 17, 2007), and the ethnic riots in Osh Kyrgyzstan (June 5-June 19, 2010) saw very few claims.

Figure 1: Fifth Column Claims Over Time (Number by Year)

I break down fifth column claims into three types. First is the “classic” type in which representatives of an ethnic group are said to be working with an outside (usually neighboring) state against the interests of the state in which the group resides. An example is the claim in 2010 by Russia’s FSB head Nikolai Patrushev that Georgian special services maintain contact with militants in the North Caucasus and there was a “Georgian trace” in the Moscow metro terrorist attacks. I refer to this type of claim as ethnic.

A second type describes the collaboration of people with presumed grievances against the state with outside supporters. They can be self-identified opposition activists, or politicians who are on the outs with the regime. An example comes from Moldova, when the opposition demonstrated against apparently fraudulent elections in April 2009. The speaker of parliament (and other officials) accused Romania of sponsoring the protests and called it an attempted coup. I call this type of fifth column claim subversive.

A third, less recognized type, involves politicians who are said to be secretly working to advance the interests of a foreign state. The analogy of puppeteering is often invoked, as the hostile power “pulls the strings” of an outwardly honest politician. An example comes from Vladimir Bondarenko, an editor of the nationalist publication Zavtra, who claimed that Yeltsin’s assault on Duma and murder of hundreds of people in 1993 was a well-planned operation backed by the West to frighten Russia. I call this claim collusive.

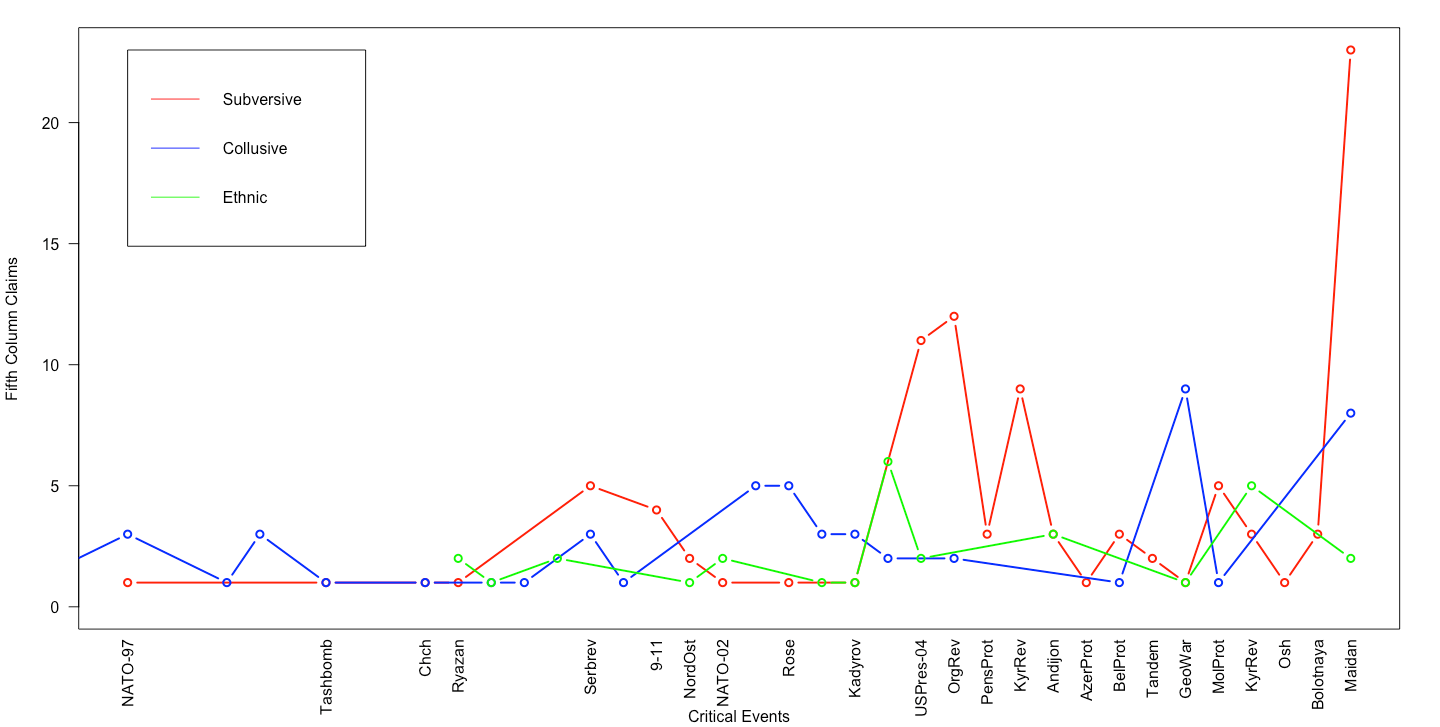

Breaking the data down in this way reveals 29 ethnic, 99 subversive, and 55 collusive fifth column claims. As Figure 2 shows, there are sporadic collusive claims before 2000, as Yeltsin and liberal reformers were accused by nationalists of doing the bidding of the West. There are spikes in subversive claims before and during mass protests in Ukraine (2004) and Kyrgyzstan (2005). Collusive claims reappear during the Georgia War (2008) and Euromaidan (2014), when Saakashvili and Yanukovych were branded as stooges of the US and Russia, respectively.

Figure 2: Fifth Column Claims by Type

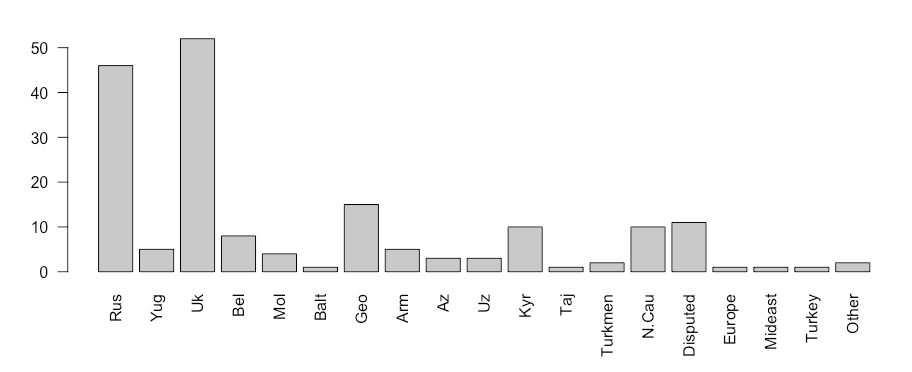

Where does fifth column activity take place? According to those making the allegations, it occurs disproportionately in Ukraine (52), Russia (46), Georgia (15), the disputed territories Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Transdniestra, and Nagorno-Karabakh (11), the North Caucasus (10)[2], and Kyrgyzstan (10). Many states had two or fewer subversive claims (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan), and there were no collusive claims in Central Asia or Azerbaijan. Figure 3 shows this distribution.

Figure 3: Where Does Fifth Column Activity Take Place? (Number by Location)

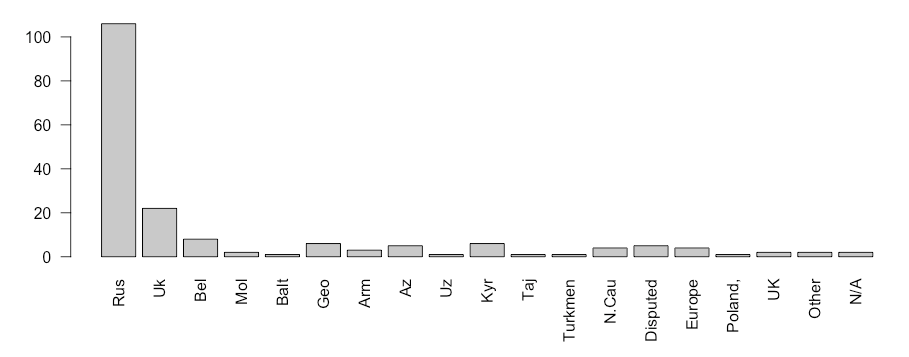

However, the country where the claim is made is not necessarily where the suspect activity takes place. If instead we look at the origins of fifth column accusations, as seen in Figure 4, it is clear that most emanate from Russia. Which Russians? The majority of claims are made in editorials in (usually nationalist or Communist) newspapers such as Sovetskaya Rossiya (50), with somewhat fewer being voiced by various public intellectuals and “experts” (20). Only 11 can be attributed to the “Kremlin” as such: the president (3), other members of the executive (3), and representatives of the security services (5). An additional 11 were made by legislators and nine by other politicians, most of whom were at least sympathetic to the Kremlin for most of Putin’s presidency.

Russia’s commentators take interest not only in political activities on Russian soil, but also in events that take place in countries of geopolitical interest, most notably Ukraine and Georgia. Russia set the regional agenda through claims that local actors were collaborating with, or sponsored by, hostile forces in the West. In many claims, the villains were working to gain influence in a neighboring state for the implied or explicit purpose of weakening Russia.

Figure 4: Where Do Fifth Column Accusations Originate? (Number by Location)

Further analysis reveals the type of claims made by Russians. Subversive claims were made about Ukraine 22 times by Russian commentators and 13 times by Ukrainians accusing the opposition of Western sponsorship. Subversive claims by Russians were most likely to appear during the Euromaidan (15), the Orange Revolution (5), and the period around the U.S. presidential election of 2004 (7), which happened to coincide with the leadup to the Ukrainian presidential election. Subversive fifth column claims taking place in Russia (15 total), by contrast, were distributed across events in the second half of the 2000s.

It was not only Russians who had an interest in making fifth column accusations and Russians were not equally prolific at all times. Imperiled leaders in Ukraine (2004), Kyrgyzstan (2005), Azerbaijan (2006), and Belarus (2006) also made their share of fifth column allegations. Perhaps surprisingly, there were only two fifth column claims surrounding the controversial Russian parliamentary election of December 4, 2011, one of which was Putin’s infamous charge that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton “gave the signal” for the demonstrations. That event also saw four conspiracy claims involving the U.S. or the “West” alone but not as backers of fifth columns. There were also no fifth column claims made during the January 2005 demonstrations against pension reforms (though there were purely domestic charges that the Communist Party was responsible), possibly because the protesters—seniors who represented Putin’s political base—were less plausible as the puppets of foreign powers.

Another contentious event, the terror attacks in Beslan in 2004, produced three claims that the West was supporting terrorists in Russia, which I consider ethnic because the attackers were presumed acting based on an identity-related motivation. Claims about ethnic fifth columns follow their own logic, occurring not as an outgrowth of regime contention, but in the context of conflict: they are most frequently made by Russians about militant groups in the North Caucasus receiving outside support (7), followed by claims of Western support for Islamic groups that carry out terrorist attacks in Russia proper (5).

Fifth Columns March On

Though the results are preliminary, the findings both affirm some conventional wisdoms and raise new questions. Fifth column claims have increased over time and are most often made by Russians, most often about geopolitically important countries at geopolitically salient times. Subversive claims are the most common, which makes sense given that regimes in the region fear political opposition more than ethnically based uprisings. Collusive claims, which are less often discussed, were also a popular type of accusation.

Although Russian officials made a small portion of the claims themselves, politicians loyal to the Kremlin and media outlets that increasingly came under state control often reflected the Kremlin’s positions, and more so as Putin gained strength domestically. While these findings may suggest that claims about fifth columns are a fixation of the Kremlin and its allies, intended to demonize Russia’s adversaries, the fact that claims tend to spike during particular destabilizing events (and wane during others) suggests that they are selectively invoked, and reactive rather than strategic. Regimes in the region do not put out a constant drumbeat of claims—perhaps because it would cheapen their rhetoric at times when it is a more urgent priority. The times and places where they occur show instead that they are a product of uncertainty and threat, and are characteristic of a region unsettled by the prospect, partly real and partly imagined, of outside interference.

Scott Radnitz is Associate Professor and Director of the Ellison Center for Russian, East European, and Central Asian Studies at the University of Washington.

[PDF]