(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) Analysts have devoted considerable attention to the rise of Sinophobia in Central Asia.[1] Chinese loans, we are told, are forcing Central Asian states into ever-growing dependency on Beijing. Chinese companies setting up shop in Central Asia crowd out local industry and employ Chinese nationals rather than local residents. And to add insult to economic injury, China threatens Central Asians’ ethnonational future. Chinese men are marrying Central Asian women at alarming rates and Beijing is “reeducating” Central Asian co-nationals across the border in Xinjiang. These Sinophobic narratives are commonplace across Central Asia. Focusing on Sinophobic narratives, however, overlooks a curious paradox: Central Asians, when surveyed about their views of the Chinese government, are more likely to approve than disapprove of Beijing. That said, only a minority of Central Asians actually do express approval of the Chinese government. The answer to this paradox, largely overlooked in studies of Central Asian receptivity to China, is that a vast number of Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Tajiks, and Uzbeks may simply not know enough about China to express a definitive opinion. The majority of Central Asians are not Sinophobic, they are Sino-agnostic. As this memo illustrates, not knowing about China presents both opportunities and challenges for Beijing as it seeks to burnish its image in the region.

Beijing’s Uncertain Reception in Central Asia

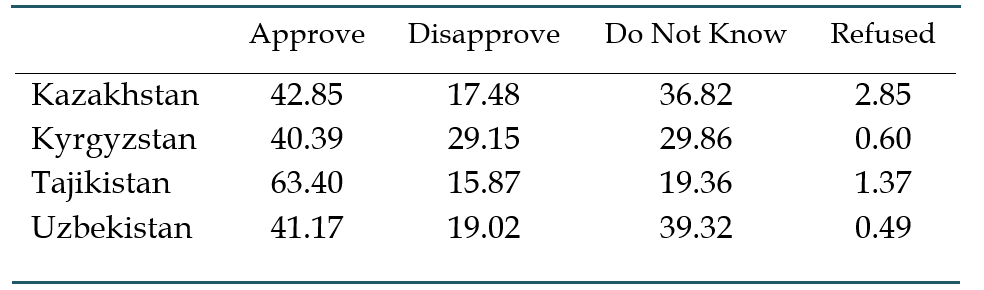

Central Asians are confident in their assessments of the great power to the north. Only 16 percent of all Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Tajiks, and Uzbeks surveyed in Gallup’s 2006-2018 annual World Polls punted on the question: “Do you approve or disapprove of the job performance of the leadership of Russia.” Most Central Asians—78 percent—approve of the Russian leadership and only six percent disapprove. China, despite the fact that it shares a border with three of the five Central Asian states (Russia shares a border only with one Central Asian state, Kazakhstan), elicits uncertainty. One third of Central Asians in Gallup’s 2006-2018 World Polls chose to express neither approval nor disapproval of the Chinese leadership. As Table 1 illustrates, Central Asians are far more likely to express uncertainty about the Chinese leadership than they are to disapprove of Beijing.

Table 1: Percent Approval of Chinese Leadership

Including “Do Not Know Responses,” Gallup World Poll Surveys, 2006-2018) [2]

Making sense of Central Asians’ uncertainty toward Beijing is a difficult proposition. As Central Asians become more familiar with China, uncertainty may be replaced with approval of the Chinese government. Conversely, Central Asians may grow more antagonistic toward Beijing if the Chinese government fails to address the anti-Chinese narratives proliferating in the region. Much will depend on how Beijing plays its economic hand and whether it ups its soft-power game to counter the region’s inchoate ant-Chinese populism.

The Uncertain Benefits of Economic Centrality in Central Asia

China is Central Asia’s most important economic partner. It is the largest export destination for Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, consuming 13 percent of Kazakh exports and nearly all—83 percent—of Turkmen exports. China, moreover, is the leading source of imports for Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. Just over 40 percent of Tajik and Kyrgyz imports and nearly one quarter of Uzbek imports are from China. The infrastructure demands of China’s Belt and Road Initiative hold the promise of establishing Beijing as the region’s leading source of foreign direct investment for decades to come. In at least two Central Asian countries, this promise is already being realized. In 2017 China was the largest foreign direct investment (FDI) provider to Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, accounting for 66 and 27 percent of all FDI respectively. Once inextricably linked to Russia, Central Asia today has reoriented its economies toward China.

Chinese investment has resulted in real gains for Central Asian economies and in Central Asians’ daily lives. These gains are perhaps most visible in the region’s transport infrastructure. A core objective of China’s Belt and Road Initiative is to improve connectivity between Chinese producers and markets to the west. Beijing is also keen to facilitate the flows of natural resources from Central Asia to China. Thus, for example, China has built mountain tunnels in Tajikistan and is building them in Kyrgyzstan. These tunnels not only facilitate trade, they drastically reduce travel time between major population centers. In Kazakhstan, Beijing has promised $1.9 billion in funding to build a light-rail system in the capital, Nur-Sultan (formerly named Astana). China similarly has extended offers to Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan to build new rail links that not only would facilitate transportation in these countries, but would also afford Beijing an overland route to the west that bypasses Russia.

Along with these gains, however, have come concerns that Central Asian governments are becoming too dependent on Beijing. China holds 45 percent of Kyrgyzstan’s external debt, 40 percent of Tajikistan’s external debt, and 21 percent of Uzbekistan’s external debt. Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are among eight countries that the Center for Global Development has identified as being “of particular concern” due to indebtedness to Beijing. Notably, in two other countries “of particular concern”—Djibouti and Pakistan—China has used loans to win land. In return for $1 billion in loans, Djibouti agreed to host Beijing’s first military base outside of China. And in Pakistan, where China has extended over $10 billion in loans, Beijing now controls the Gwadar Arabian seaport.

China has yet to leverage loans for land in Central Asia. Beijing has, however, engaged in other forms of deal-making that, at the very least, give the appearance of undermining Central Asian state sovereignty. In 2018, Tajikistan’s Rahmon government, unable to repay $332 million in Chinese loans for the modernization of the Dushanbe power plant, handed indefinite control of the Upper Kumarg gold mine to the Tebian Electric Apparatus Stock Company (TBEA), the Chinese company that was contracted for the power-plant’s retrofit. The Kyrgyz government, also using Chinese government loans, contracted TBEA to modernize Bishkek’s power plant. This plant failed in January 2018, after the TBEA retrofit, leaving many in the Kyrgyz capital without heat. Six former Kyrgyz ministers, including two former prime ministers, are currently on trial for siphoning off $111 million in funds from the $386 million contract. Beijing may not be at fault for the Tajik and Kyrgyz governments’ mishandling of development loans. The scandals that surround these loans, nevertheless, stand at odds with the economic development image China wishes to convey.

Anti-Chinese Sentiments

Central Asian elites’ dependency on and corrupt use of Chinese development loans constitute only one potential driver of anti-Chinese sentiment in the region. Central Asia, like much of the world, has seen growing populism over the past five years and China has increasingly become the target of rising ethno-nationalism across the region. Some of the ethno-nationalist charges against Beijing are not without merit. An estimated one million ethnic Kazakhs and half million ethnic Kyrgyz live in Xinjiang. China’s recent attempts at “reeducating” these Kazakh and Kyrgyz Muslim minorities, along with the millions of Uighurs who also live in Xinjiang, has led to a spike in anti-Chinese protests in Central Asia. In December 2018, protesters gathered outside the Chinese embassy in Bishkek to demand an end to “Chinese fascism” and an explanation for why ethnic Kyrgyz were being held in the Chinese camps. In Kazakhstan, the grassroots organization Atajurt Eriktileri has publicized the detention of upwards of 10,000 ethnic Kazakhs in northwest China, and in late 2018 the Kazakh foreign minister acknowledged his office had received over 1,000 letters asking for help in securing the release of family members in Xinjiang.

While some Central Asians are worried about their co-nationals in northwest China, others are worried about their countrywomen at home. A Kazakh news website, Nur.kz, reported in January 2017 that a group of 15 well-heeled Chinese bachelors enlisted a Nur-Sultan-based marriage agency to help them find Kazakh brides. The agency had placed an ad on Facebook, and the week after the Facebook ad appeared, protesters gathered on Nur-Sultan’s central square with placards reading “Men defend the homeland, women defend the nation!” The protesters demanded a prohibition against Kazakh-Chinese marriages and, short of that, a requirement that would-be Chinese grooms pay a tax of $50,000 in order to marry a Kazakh woman. In Kyrgyzstan, political pundit Melis Murataliev claimed in a February 2018 lecture that 30,000 Chinese men had married Kyrgyz women. Murataliev went on to explain, “I have nothing against the Chinese, but these numbers should make you think.” Murataliev’s comments were echoed in focus groups we conducted in Kyrgyzstan in May and June 2019. A participant in one of our Bishkek focus groups noted, for example, “adults understand that our Kyrgyz girls marry Chinese men… this is not good.”

The grounded grievance that Beijing poses a threat to co-nationals in Xinjiang and the more questionable objection that Chinese men are absconding with Central Asian women are but a few of the narratives driving anti-Chinese populism in the region. Other complaints focus on purported Chinese attempts to gain control over Central Asian land and on Chinese migrants’ taking over local industries and commerce and thereby squeezing Central Asians out of coveted local jobs. These anti-Chinese narratives receive considerable attention in the regional media. As the Gallup World Poll survey results illustrate, however, this newly emergent anti-Chinese feelings does not appear to have taken hold among Central Asians broadly.

Age and Anti-Chinese Outlooks

The modal response among participants in the Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Tajik, and Uzbek 2006-2018 World Polls is one of approval of the Chinese leadership. Although only a minority of Central Asians in the Gallup World Polls approve of Beijing, even smaller minorities disapprove or are unsure of their views of the Chinese government. Somewhat troubling for China, the proportion of Central Asians who disapprove of Beijing has grown from 18.3 to 26.2 percent over the past twelve years while Beijing’s approval rating has declined from 44.3 to 39.2 percent. All, though, is not bad news for China’s fortunes in Central Asia. Central Asian youth—those 30 and younger—are both more upbeat on Beijing than are older Central Asians and view the Chinese government more favorably today than did their counterparts in 2006. In 2006, 39.6 percent of Central Asians 30 and younger approved of the Chinese government. In 2018, the Chinese government’s approval among Central Asian youth had risen to 42.5 percent.

There are several potential explanations for why young Central Asians are more positively inclined toward Beijing than are older generations. Anti-Chinese narratives may resonate more among older Central Asians familiar with Sino-Soviet rivalries of the past. Another possibility, however, is that Beijing’s soft-power efforts, which are disproportionately directed at Central Asia’s youth, are gaining traction. As elsewhere in the world, so too in Central Asia is China investing in education. Beijing has established Confucius Institutes at schools and universities across the region. Moreover, it is sponsoring more and more Central Asians for study in China. In a 2013 speech at Nazarbayev University, Chinese President Xi Jinping promised 30,000 scholarships to students from the 8 Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) member countries—four of which are Central Asian states.

Xi appears to be delivering on this promise. In 2018, 11,784 Kazakhs were studying in China, placing Kazakhstan among the top 10 countries sending students to China. The Chinese Ministry of Education has not released figures for the other Central Asian countries. What is certain, though, is that through its Confucius Institutes and its scholarships, China has greatly expanded its outreach to Central Asian youth.

Conclusion

China’s efforts to reach Central Asian youth by providing educational opportunities and its efforts more broadly to increase its soft power throughout the region are in their early days. Much has been written on the limited effectiveness of these efforts. What this memo demonstrates, however, is that anti-Chinese narratives, while frequently encountered in the Central Asian press, have limited resonance among the Central Asian population at large and even less resonance among Central Asians under the age of 30. It may yet be some time before the Chinese leadership receives in Central Asia the same approval ratings that the Russian government does. Nevertheless, Central Asians are open to China and willing partners for Beijing’s ambitious Belt and Road.

Eric McGlinchey is Associate Professor in the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University.

This memo is part of a three-year project with Marlene Laruelle, “Russian, Chinese, Militant, and Ideologically Extremist Messaging Effects on United States Favorability Perceptions in Central Asia,” funded by the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Army Research Office/Army Research Laboratory under the Minerva Research Initiative, award W911-NF-17-1-0028. The views expressed here are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Army Research Office/Army Research Laboratory.

[PDF]

[1] For example, see: Kamila Eshaliyeva, “Is anti-Chinese mood growing in Kyrgyzstan?,” openDemocracy, March 2019.

[2] Means are calculated using survey weights. The Uzbek 2006-2018 mean scores do not include 2007 survey responses. Uzbekistan 2007 Gallup World Poll data is unavailable for 2007.