(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) What were the origins of separatism in the Donbas? When the Luhansk People’s Republic (LNR) and the Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR) were first proclaimed in early April 2014, their provenance was unclear, to put it mildly. Their self-appointed leaders were not well known. The organizations they represented before 2014 could generously be described as politically marginal. And yet, support for separatism in the Donbas began to grow. By the time armed militants began taking over regional government buildings in Donetsk in early April, large crowds accompanied them.

To be sure, only a minority of the general population—18 percent in Donetsk and 24 percent in Luhansk—supported the building seizures. But a more sizeable minority backed separatist goals: 27.4 percent of respondents in Donetsk and 30.3 percent in Luhansk reported that their region should secede from Ukraine and join Russia; while another 17.3 percent and 12.4 percent prevaricated, answering, “difficult to say, partly yes, partly no.” By spring and early summer, popular support for the DNR and LNR reached approximately one-third of the population. Of course, fear of the brutal violence visited on putative political enemies by DNR and LNR thugs could explain why some people said that they supported the republics. Yet well-attended separatist demonstrations, in combination with statements made by participants at these events, provide additional evidence of local support for separatism in the DNR and LNR.

Why did a significant, albeit minority, portion of the Donbas population back separatism? Why did the Euromaidan revolution generate a relatively sudden and deep sense of alienation among many residents in Donetsk and Luhansk? Understanding the sources of popular alienation not only sheds light on the general phenomenon of separatism; it is of critical importance to Ukraine if it hopes to eventually reintegrate the Donbas.

I identify a range of reasons why ordinary people began to support separatism by examining grievances in Donetsk and Luhansk in late 2013 and early 2014. The analysis goes beyond a one-dimensional understanding of separatists as pro-Russian, motivated solely by an enduring orientation to Russia that has not changed over time, whether due to ethnic or linguistic identity, or political loyalty.

Political loyalty to Russia can account for a portion of the support for separatism, especially among those in the older generations who never accepted the USSR’s collapse and exhibited a strong sense of nostalgia for the Soviet Union. They identify present-day Russia with the USSR, and deepened their allegiance to Russia as the Maidan demonstrations in Kyiv embraced the European Union. As Boris Litvinov, one of the leaders of the DNR and a self-described “committed communist” declared:

Over the past 23 years Ukraine created a negative image of the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union was not about famine and repression. [It] was mines, factories, victory in the Great Patriotic War and in space. It was science and education and confidence in the future.

Yet for others in the Donbas, support for separatism was not primarily about joining Russia but was motivated by various forms of material interest, or by a sense of betrayal by Kyiv and the rest of the country inspired by the Euromaidan events. In terms of material interest, I examine two kinds of grievances:

1) claims of discriminatory redistribution within Ukraine; and

2) perceptions of the negative effect of potential EU membership on economic welfare, due to austerity policies or the foregoing of trade with Russia and the Eurasian Customs Union (ECU).

In terms of a sense of betrayal by Kyiv, I discuss specific developments related to the Euromaidan, including:

1) Kyiv’s condemnation of Berkut special police, many of whom came from the Donbas;

2) the government’s failure to repudiate the Ukrainian nationalist far right which, as political scientist Serhiy Kudelia[1] has argued, generated resentment and fear; and

3) the new Ukrainian parliament’s attempt to annul the law on Russian language.

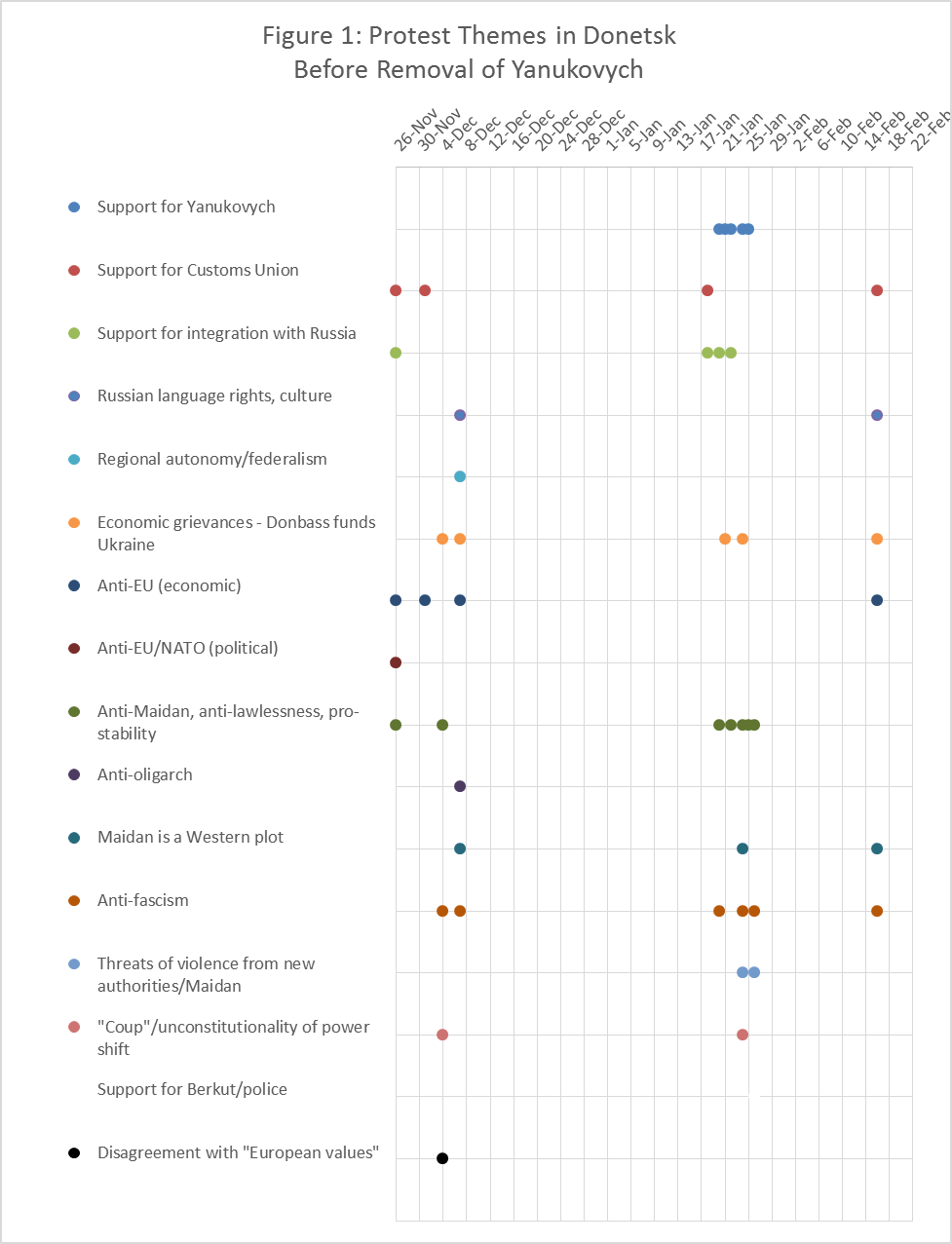

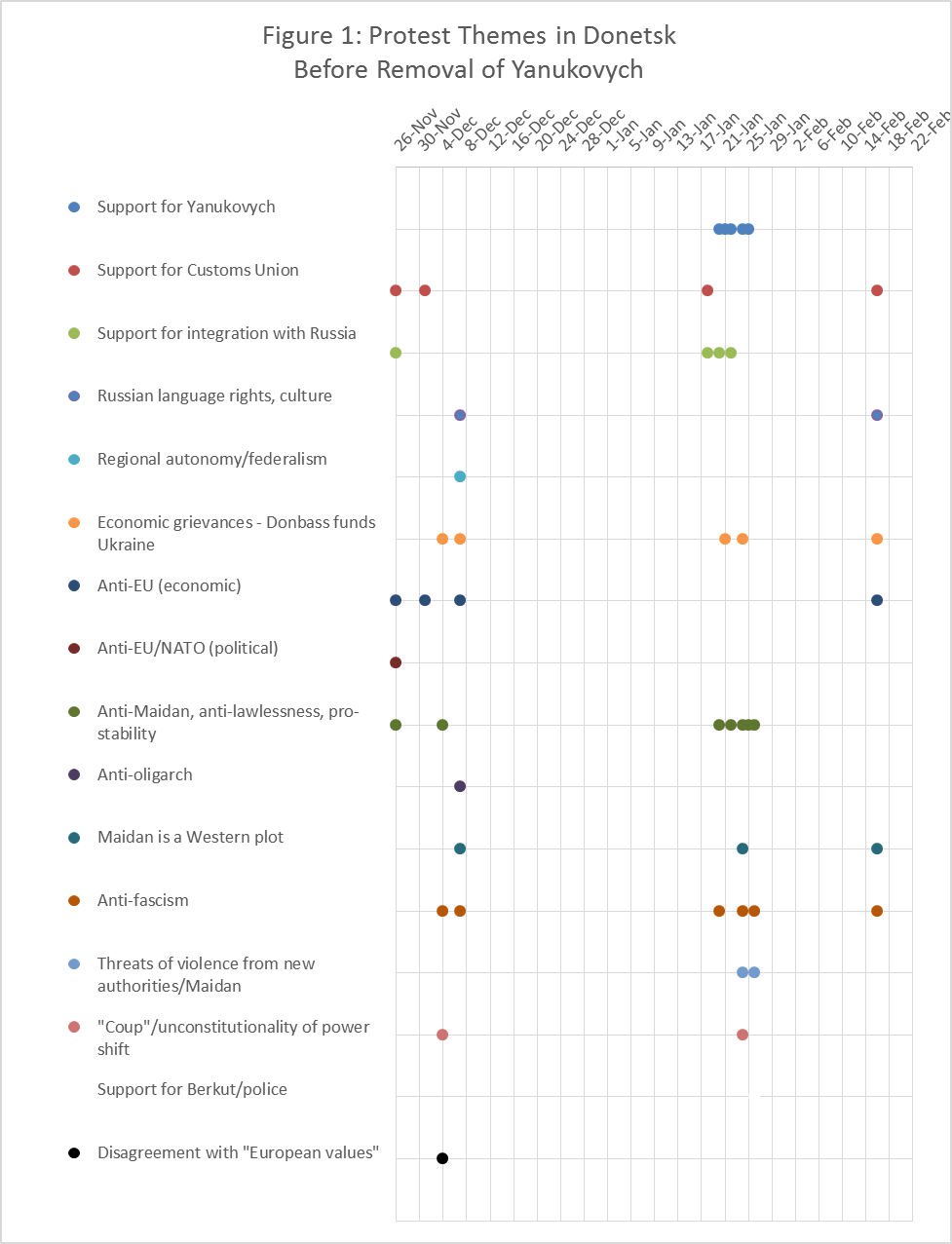

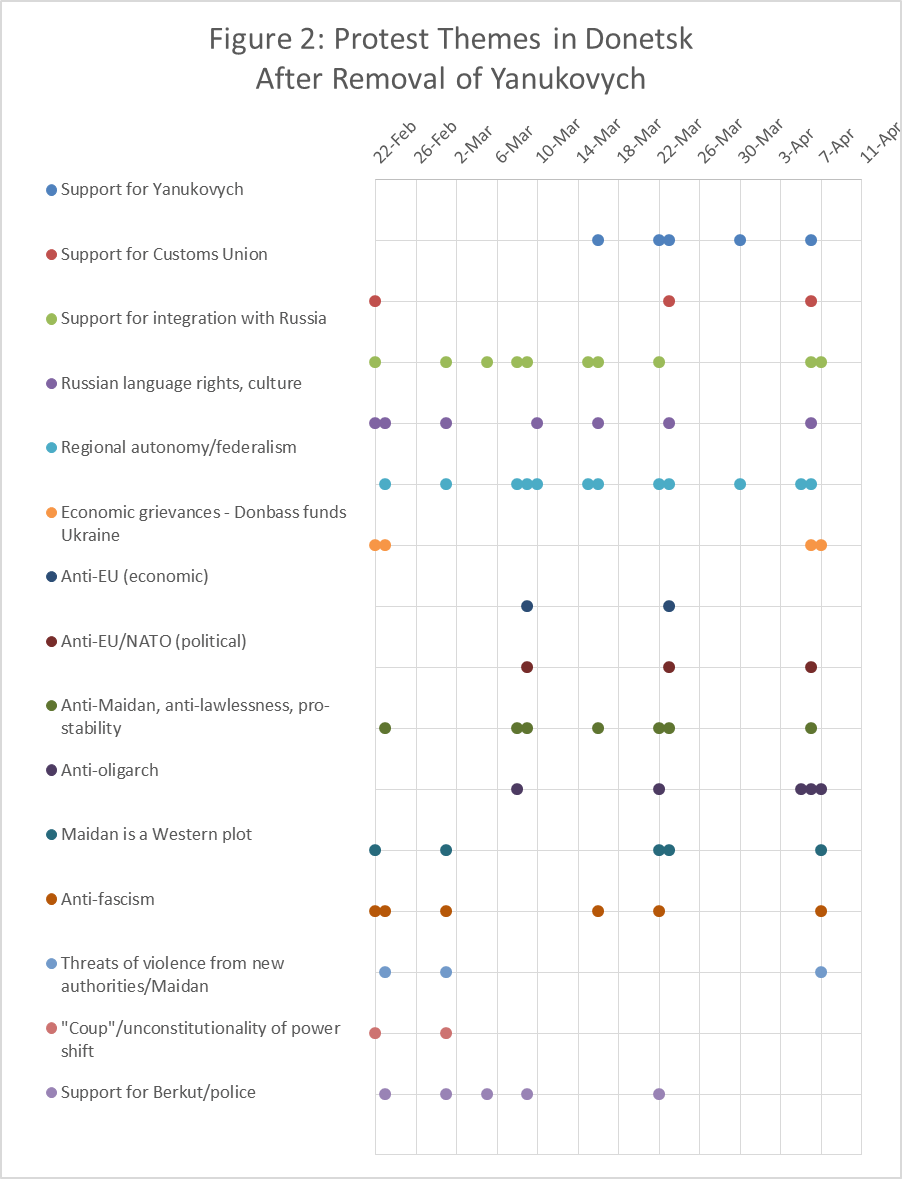

I provide evidence in support of these arguments based on an analysis of an original database of demonstrations held in the Donbas—the so-called anti-Maidan and pro-Russian rallies. The database was created using a combination of Western and local (Russian and Ukrainian) media reports and videos. Themes articulated by participants at the demonstrations are reported in Figures 1 and 2.

Discriminatory Redistribution

Like the striking miners in 1993 who complained that the Donbas subsidized Ukraine’s poorer regions and received little investment in return, some residents in 2014 believed that, as the industrial heart of Ukraine, their region contributed more than its fair share to the federal budget. As Figures 1 and 2 indicate, claims of discriminatory redistribution (and related themes, such as: “Kiev maidanaet, Donbas rabotaet” [“Kyiv protests (literally “maidans”) while the Donbas works”]) were raised at rallies both before and after President Viktor Yanukovych’s removal. For example, a young worker at an April demonstration told an interviewer:

The Donbas has always been an industrial region. I work at a factory. People are being suspended without pay. People aren’t receiving salary or benefits.…They told us we didn’t produce enough, but really all our money was sent to the Army.

A middle-aged woman speaking at a rally in February 2014 made a similar complaint: “People who were standing on the Maidan are getting pensions. We are working for them!” By 2014, the Donbas was no longer contributing as much to the federal budget as it had earlier and instead received significant subsidies from Kyiv. In separatist movements, however, perceptions of economic conditions rather than actual conditions are what matter in motivating people. In the Donbas, many people perceived their region as a victim of unfair redistribution, giving rise to a sense of estrangement from the rest of the country.

The Customs Union versus the European Union

Support for the Eurasian Customs Union and opposition to the EU—the issue that sparked the Euromaidan protests—were frequently heard at demonstrations. Large majorities in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions (72.5 percent and 64.3 percent respectively) favored joining the Customs Union over the EU. These percentages were considerably higher (from 26 to 42 percent) than in neighboring regions in eastern and southern Ukraine. Opposition to the EU could indicate a general geopolitical orientation toward Russia, but it also indicated beliefs about how EU membership would damage Ukraine’s economy and peoples’ livelihoods. Some residents, especially those on fixed incomes, opposed the austerity measures that the EU would impose on Ukraine. Others, such as industrial workers, understood that joining the Customs Union would maintain trade ties with Russia and other post-Soviet states and therefore preserve jobs and the status quo. This was a crucial goal since the Donbas is dominated by Soviet-era mining, metallurgy, and machine building industries that are less competitive on European markets. The choice in favor of the Customs Union mimicked one of the enormously popular goals of the 1994 autonomy movement in the Donbas: full integration with the CIS economic union, for which 89 percent of the population in Donetsk and 91 percent in Luhansk voted in a popular referendum. When Pavel Gubarev, a founder of the DNR, was asked directly about why people support separatism, he shifted from discussing the Russian ethnic and historical elements of Novorossiya to the calculations of workers. Elites have their own reasons for supporting separatism, he explained, but for working people:

in the manufacturing sector…everyone very clearly understands, for example, why the factory “Motor Sich” [an airplane engine manufacturer] stopped working….[It] stopped because Russia is not buying….Of course people understand that if Zaporizhia [a city in southeast Ukraine] is not pro-Russian then they will be out of jobs and that’s thousands of employees. And it’s the same thing with other enterprises in the former southeast of Ukraine—Novorossiya.

The Berkut

One of the ways that the Euromaidan gave rise to a sense of betrayal and alienation among residents in the Donbas concerns the Berkut special police. Founded in 1990 as an elite force to manage crowd control and fight organized crime, Yanukovych used it to violently subdue the Euromaidan protesters in Kyiv. As a result, the Berkut were labeled violent criminals. In the Donbas, however, they were perceived to be loyally executing their duties. The Berkut’s reputation in the country held special significance for the Donbas since many of its troops came from Donetsk. At demonstrations in April 2014, mothers stood at the front of the crowd holding pictures of sons who had been killed or wounded during violent episodes at the Euromaidan, while crowds chanted “Berkut, Berkut.” After Yanukovych’s ousting, the Ukrainian government disbanded the force. According to a Berkut veteran in Donetsk,

It’s simple betrayal. How else can you describe it if in its 25 years of existence, the Berkut carried out all its orders? Now they want to get rid of it because someone has decided that they didn’t act correctly? And….if it wasn’t correct to act like that in Kyiv, but if it happens here then it is correct?

The statement of another Berkut sympathizer who supported autonomy for the Donbas expressed a sudden sense of loss and betrayal by not only Kyiv but the rest of Ukraine:

We had a country and now we don’t. The whole of Ukraine couldn’t care less about the east. Are we citizens or not? They insult our compatriots. They are heroes, and we’re cattle—working cattle who contribute to the budget.”

Ukrainian Ultra-nationalism

Another important way in which events of the Euromaidan generated alienation among Donbas residents concerned the new government’s perceived embrace of Ukrainian ultra-nationalism. The ethnically exclusivist view of Ukrainian nationhood that characterized one strand of political discourse in Ukraine for years was perceived by many in the east to have its moment during the Euromaidan. Following the critical role played by Svoboda and Right Sector, Ukraine’s new government failed to criticize xenophobic discourses that scapegoated ethnic Russians for Ukraine’s problems. Instead, the government appointed a former leader of a neo-fascist party, Andriy Parubiy, to lead the national security and defense council. Anxiety about Ukrainian ultranationalism is evident in many statements made by demonstrators, such as one woman who spoke at an anti-Maidan demonstration:

Did you hear what they shouted on the Maidan yesterday, when they beat the defenseless men, elderly women, children? They shouted: Seig heil!, Rudolf heil!, Hitlerjugend!, SS!….What is happening in our country? Neofascism is spreading…

As Kudelia argues, fear radicalized residents of the Donbas who witnessed nationalist paramilitary groups violently seizing buildings and battling police at protests throughout Ukraine. In the words of one young man, speaking at a rally in Donetsk in February:

Right Sector is just a bunch of fascists who trained for 10 years and didn’t have anywhere to direct their rage. We’re just pieces of meat to them….Right Sector said that they want to destroy all of eastern Ukraine and make us their slaves.

Russian Language: Do Ukrainophones and Russophones Form Political Blocs?

Finally, the status of the Russian language became a popular subject at separatist rallies following Yanukovych’s departure. Russian is the dominant language in the Donbas, and many of the protests included the demand that Russian be made an official state language. Some protesters believed that the post-Maidan authorities in Kyiv would ban Russian, most likely because the new Ukrainian parliament as one of its first acts in office voted to annul a 2012 language law granting Russian official regional language status. The vote—though quickly reversed—seems to have signaled to some protesters that discriminatory acts against Russians and Russian-speakers would follow. As a speaker at a communist rally in Donetsk stated:

Now the authorities who have won in Kyiv declare that Russian is the language of occupiers. It’s not right….If somebody thinks that it’s their right to fight Russification, I think it’s our right to fight Ukrainianization because it’s more enjoyable and convenient to speak in our native language.

Another man defending the Russian language at a rally in Luhansk ascribed more hostile intentions to Kyiv: “Having crushed our culture, they will crush us….”

Interestingly, however, polling data suggests that a grievance about Russian language was not shared by the majority of Russian-speakers in the Donbas: only 9.4 percent of respondents in Donetsk and 12.7 percent of respondents in Luhansk, when asked “What makes you anxious most of all at the present moment?”, answered “the imposition of one language” Likewise, in an International Republican Institute (IRI) poll, 74 percent of respondents in eastern Ukraine (Donetsk, Dnipropetrovsk, Kharkiv, and Luhansk) answered “definitely no” or “not really” when asked: “Do you feel that Russian-speaking citizens of Ukraine are under pressure or threat because of their language?”

This disconnect between poll results and the discourse of some demonstrators concerning Russian suggests that Kyiv’s bungled attempt to ban the regional language law was perceived in various ways by the Russophone population in the Donbas: some shrugged it off while others felt threatened. Linguistic identity apparently did not automatically translate into a grievance over language.

Moreover, the implosion of the Novorossiya project, in which the DNR and LNR announced a Federal State of New Russia (Novorossiya) that would incorporate eight regions of Ukraine, also suggests that cultural and ethnic issues failed to resonate with Donbas residents. The Novorossiya doctrine most closely resembles standard nationalist ideology in its historical claim to a defined territory and assertion of indigenousness (i.e., that inhabitants of Novorossiya settled the territory prior to Ukrainians). The idea of Novorossiya can be traced to an early-1990s fringe intellectual movement led by Professor Oleksiy Surylov of Odessa State University. Surylov championed the establishment of Novorossiya as an ethnic state, arguing that the residents of southern Ukraine formed a separate ethnos—the Novorossy. The movement demanded autonomy within a federal Ukraine but attracted virtually no popular support. In 2005, when the opposition group “Donetsk Republic,” whose leaders would later found the DNR, again tried to advocate the creation of a republic spanning southeast Ukraine, it failed miserably. In the current incarnation of Novorossiya, other cities and regions of Ukraine’s south and east refused to participate. By May 2015, one year after its official birth, the leaders of the Novorossiya officially declared the project defunct. Thus, during the period of intense political upheaval following the Euromaidan and the conflict in eastern Ukraine, it appears that ethnic Russians did not unite behind a program of nation-building.

Conclusion

There is a good deal of diversity among people commonly labeled pro-Russian separatists. Analysis of grievances articulated at demonstrations in late 2013 and early 2014 indicates that while some supporters of separatism maintained a pro-Russian stance based on Soviet-era political loyalties, others were motivated by more recent considerations of material interest, such as perceptions of discriminatory redistribution within Ukraine or concerns about the economic effects of joining the EU as opposed to the Eurasian Customs Union. Other collective grievances developed in response to specific developments surrounding the Euromaidan, including the criticism of the Berkut special police, Kyiv’s perceived support of the nationalist far right, and Kyiv’s attempt to annul the language law that gave Russian regional status.

However, polling data indicating that a majority of Russophones in the Donbas were unconcerned with the status of Russian, as well as a lack of support for the Novorossiya project, indicates that politicians within the Donbas faced obstacles in their attempts to draw boundaries between ethnic Russians and Ukrainians, and between Russophone and Ukrainophone populations. This suggests that ethnocultural differences among the Donbas population did not spontaneously translate into political grievances. While this subject deserves more research, we may be cautiously optimistic that the grievances that did develop in the Donbas are more amenable to dialogue and policy intervention than is generally thought.

Elise Giuliano is a Lecturer in the Department of Political Science at Columbia University and Academic Advisor of the MA Program in Russia, Eurasia and Eastern Europe at Columbia’s Harriman Institute.

[PDF]

[1] See Serhiy Kudelia, “Domestic Sources of the Donbas Insurgency,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 351, September 2014.

For further reading:

Serhiy Kudelia, “Domestic Sources of the Donbas Insurgency,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 351, September 2014.

Volodymyr Kulyk, “One Nation, Two Languages? National Identity and Language Policy in Post-Euromaidan Ukraine,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 389, September 2015