(PONARS Policy Memo) On October 3, 2017, Vladimir Vasiliev was appointed acting head of the republic of Dagestan. Vasiliev replaced the outgoing leader, Ramazan Abdulatipov, who had guided the region for just over four years and cited age as the key factor in his departure. In fact, Abdulatipov was generally ineffectual at combating corruption and the patronage networks that define the region’s economy. Vasiliev, an ethnic Russian who is only three years younger than Abdulatipov, was positioned as an outsider who could counter these shortcomings and bring corrupt practices to heel. Just prior to his appointment in Dagestan, Vasiliev was the leader of United Russia’s coalition in the State Duma. More broadly, Vasiliev’s appointment is a departure from two trends apparent in other republic heads in the North Caucasus: the outsourcing of management to local proxies with established kinship networks—which has been termed the Kadyrovization of the North Caucasus leadership—and the selection of leaders with extensive experience in the country’s security apparatus. Corruption has supplanted security as Moscow’s main concern in Dagestan.

Dagestan—Legacy and Reality

Dagestan is arguably the most important of Russia’s 21 national republics. It is the third largest in terms of population, behind the Volga republics of Bashkortostan and Tatarstan. However, it is roughly equal with Bashkortostan in its non-Russian population and 88 percent of the population belongs to one of the region’s minority (at the national level) ethnicities. Dagestan is one of the few regions in Russia that experienced a demographic increase during the last intercensal period (2002-2010), with roughly twenty percent growth over those eight years.

The list of challenges facing Russia in Dagestan includes a low-level yet ongoing conflict, religious extremism, and economic inequality exacerbated by corruption. Russia’s long war in the North Caucasus has lasted much of the period since 1991, centering on Chechnya from 1994-1996 and 1999-2002. Attacks by insurgents against government and civilian targets in the region spread from Chechnya in the last years of the prior decade to Ingushetia, Dagestan, and Kabardino-Balkaria. Violence in Dagestan was notably high between 2009 and 2011; in the years since, Dagestan has remained the republic with the highest number of absolute conflict events, although these totals have been declining both in Dagestan and in the North Caucasus as a whole. This decline in violence is frequently linked to the rise of ISIS and the exodus of potential fighters to Syria and Iraq. Dagestan has been notably quiet for the past couple of years. The news service Caucasian Knot (Kavkazskii Uzel) reported 27 victims of armed conflict in the North Caucasus during the first quarter of 2018, on pace to be the lowest annual total in the region as a whole in the last two decades.

A majority Muslim region, the religious factor in Dagestan is complicated by the legacy of Soviet-era spiritual boards, a tradition of Sufism, and more recent inroads made into the region’s religious life by more fundamentalist elements of Islamic faith. Although a strong link between religious fundamentalism and violence in the North Caucasus exists, these fundamentalist networks also served as a basis for the organization of alternatives to the state and as a mechanism to capture economic benefits from corrupt officials.

The disparity in economic development between urban and rural—generally aligned with non-mountainous and mountainous areas of the republic—is reflected in the types of livelihoods practiced and the associated demographic trends. Dagestan’s mountain villages retain a traditional feel, though some maintain Soviet-era enterprises such as silversmithing in Kubachi. Highland residents travel elsewhere in Russia for short-term work; common destinations include the oil fields of western Siberia and Astrakhan as well as the country’s major cities of Moscow and St. Petersburg. Internal migration within the republic from the highlands to the cities has resulted in a booming population in Makhachkala, the republic’s capital on the Caspian Sea coast. One important consequence of this growth is the proliferation of unauthorized construction in the city; the urban landscape is a hodgepodge of Soviet and pre-Soviet construction positioned alongside more recent builds. In turn, the ability to allocate space for construction in Makhachkala’s crowded urban landscape has emerged as a valuable political asset.

Moscow’s main strategy for addressing the lack of economic growth in Dagestan and the wider North Caucasus has been the use of subsidies to prop up local and regional governments, although corrupt officials often siphon off these monies for personal use. Other elements of the federal center’s plan for regional development include tourism and the further growth of agriculture and hydrocarbon production.

A lagging economy, an ongoing if generally quiescent insurgency, corruption, and demographic change are the main challenges facing Dagestan today. Abdulatipov fell out of favor with Vladimir Putin mainly because of his inability to deal with corruption. Moreover, the decline of insurgent activity in the republic and broader North Caucasus is often linked to outside conditions rather than domestic developments. In turn, Vasiliev should be viewed as an outsider loyal to Moscow who can rise above the rough-and-tumble fray of local politics. This loyalty is reflected in Vasiliev’s access to Putin; in the first nine months of his tenure as acting head, the pair met face-to-face four times.

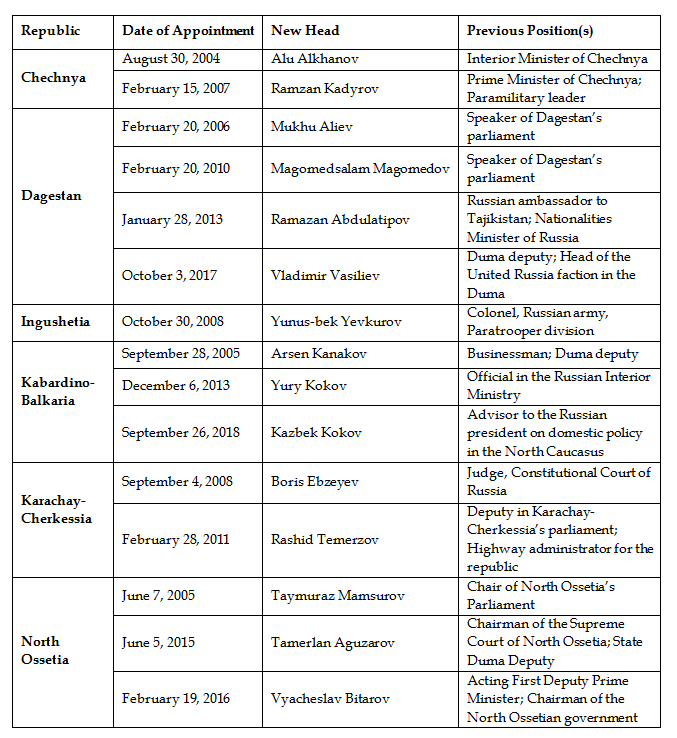

Yet Vasiliev was likely Putin’s second choice to head Dagestan. His first, Sergey Melikov, reportedly declined the position on multiple occasions. Currently first deputy director of Russia’s National Guard, Melikov was presidential plenipotentiary to the North Caucasus Federal District from 2014 to 2016. An ethnic Lezgin—Dagestan’s fourth-largest national group, generally concentrated in the republic’s south—on his father’s side, Melikov fit the profile of a republican head with a background in the security services (see Table 1). Vasiliev as a party loyalist differs from recent appointments in the republics of leaders with this military and security background.

Table 1. Leadership Changes in the North Caucasus since 2004

Leadership Politics in Dagestan since 2000

As an outsider in ethnic and political terms, Vasiliev’s leadership marks a substantial departure from the management of Dagestan during the past quarter-century. Magomedali Magomedov, a former Soviet apparatchik, secured control of Dagestan’s executive during the transition period from communism, culminating with the passage of the republic’s revised constitution, in July 1994. An ethnic Dargin, the second largest of Dagestan’s national groups, Magomedov effectively maneuvered to maintain control of the chairmanship of the republic’s state council—the stand-in executive body outlined in the constitution that had representatives from each of Dagestan’s 14 main ethnic groups. Magomedov maintained control in Dagestan through 2006, when he resigned and was replaced by his longtime political rival, Mukhu Aliyev (an ethnic Avar, Dagestan’s largest national group, and another former communist); Magomedov’s son, Magomedsalam, rotated into Aliyev’s old position as chair of the republic’s legislature.

Putin shifted away from direct elections—although no such election had yet occurred in Dagestan due to its national diversity and constitutional structure—to the top-down appointment of regional heads following the September 2004 terrorist attack at the schoolhouse at Beslan, North Ossetia. The Kadyrovization of the North Caucasus’s leadership—so named after the federal center’s bargain with the Kadyrov clan in Chechnya—saw the appointment of either local proxies with kinship networks or the insertion of individuals with security experience into executive positions. If anything, the former profile was more common before Putin’s third term, with a shift in criteria occurring since 2012.

Moscow appointed Aliyev and then the younger Magomedov (in 2010) to lead Dagestan; however, both were unsuccessful in countering the key issues of corruption and political violence. Putin eventually turned to Abdulatipov—although an ethnic Avar, something of a political outsider in the republic who had previously chaired Russia’s federal Council of Nationalities through 1993 and was subsequently Russia’s ambassador to Tajikistan. Following his appointment, Abdulatipov felt constrained by the quasi-consociational system that apportioned leadership positions across the diversity of national groups as has occurred throughout the post-Soviet period. In response, he dismissed his entire cabinet in July 2013, although he still maintained connections to the clan system that came to dominate Dagestani politics during his tenure as head.

In leading Dagestan, Abdulatipov—though lacking a background in the security services—railed against corruption, economic weakness in key sectors such as industry and agriculture, and the challenges of Dagestan’s Islamist insurgency. He adopted techniques against insurgents similar to those used by Ramzan Kadyrov in neighboring Chechnya. In a report, the international NGO Human Rights Watch decried the destruction of homes of insurgents’ relatives and other types of damage to civilian property. Nonetheless, the debate over Kadyrov’s effectiveness at suppressing Chechnya’s insurgency is ongoing and the decline in violence in Dagestan is frequently linked to the emergence of other battlefields for Islamists rather than the success of federal tactics.

As political violence has declined in the North Caucasus, other issues have come to the fore, including those discussed previously, such as corruption, kinship-based patronage, and economic development. As Dagestan’s acting head, Vasiliev has targeted these corrupt practices. In January 2018, Makhachkala’s mayor Musa Musayev was arrested; other arrests soon followed, including the capital’s head architect, the republic’s acting prime minister, and a number of high-ranking deputies. The architect, Magomedrasul Gitinov, was charged with damaging the city’s architectural appearance, as associated with haphazard development and building practices in violation of the city’s master plan. Embezzlement is the main charge against the other officials.

Vasiliev has also attempted to break the system of distributing leadership positions based on national identity. He dissolved the republic’s government in early February 2018, and filled key positions—for example, the prime minister role—with outsiders to the region. Although Vasiliev subsequently appointed local politicians to head the ministries of Transportation and Energy and Construction, this conciliation was viewed with some skepticism in Dagestan. Some critics of Vasiliev’s approach have appeared on social media or in the region’s newspapers; the main complaint is about the lack of coordination between Vasiliev and local elites in the crackdown on corruption.

Conclusion

Vasiliev’s appointment reinforces the importance of Dagestan to the Russian state and the fact that Putin is no longer willing to ignore the funds skimmed from the subsidies Moscow provides to Dagestan to prop up the region’s economy. Vasiliev’s crackdown on corruption has been linked by some commentators to the March 2018 Russian presidential election, as well as the local strength of the anti-corruption bloc People Against Corruption, which quickly gained prominence before the local parliamentary elections in 2016 but which was not allowed to field candidates in that vote. More broadly, the Kremlin’s refocus on Dagestan underscores continued concern for the republic as the situation evolves there. The challenge of security has been replaced with the challenge of corruption. Perhaps these evolving concerns best explain the choice of Vasiliev to lead the republicVasiliev. At the level of the state, centralization as a political process continues, as evidenced in the country’s new language law. This project of centralization is Putin’s historic mission as Russia’s leader, made most manifest in the North Caucasus over the past two decades.

Edward C. Holland is Assistant Professor in the Department of Geosciences at the University of Arkansas.

[PDF]

Homepage image credit.