(PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo) Yevgeny Prigozhin, the corrupt military contractor from St. Petersburg who funds the informal armed organization known as the Wagner Group, expanded his lucrative foreign adventures into Africa in 2018 with Russian state support. His fortunes continued to rise even after scores of his fighters were killed and wounded by a United States air strike in eastern Syria.

This memo presents (though in-text links) the most reliable evidence currently available from original Russian, French, and local African media sources about Prigozhin’s and Wagner’s 2018 activities, and analyzes the odd relationship between Prigozhin and the Russian military. It concludes that Russian President Vladimir Putin may have arranged the collaboration of the Russian military in Prigozhin’s corrupt deals in Africa in order to mend a dispute within the Kremlin elite.

Understanding Russia’s Patronage Politics

In Russia’s rough-and-tumble patron-client political system, Putin has long been the only individual with enough support across competing elite networks to maintain stability. Now, though, he is becoming what George Washington University professor Henry Hale calls a “lame duck”—an old-timer in his last constitutionally permitted term as president, whose popularity is falling as the Russian economy stagnates. If Putin appears weak, elites could desert him and throw their support behind a new challenger. Putin benefits from network infighting, since it leaves potential challengers off balance. But if conflict becomes too intense and public, elites might think Putin has lost his ability to manage rivalries effectively. Such an intense conflict may have occurred in late 2017 and early 2018.

The Wagner Group and the Russian Military

Private military companies are illegal in Russia. Despite advocates’ years-long efforts to legalize them, the Russian cabinet definitively nixed the idea in March 2018, arguing that state authorities alone have responsibility for defense and that “private armies” could seriously destabilize the country.

Yet the Wagner Group of military and police veterans and Cossacks, commanded by former Russian military intelligence (GRU) officer Dmitry Utkin and funded by Prigozhin, trains on Russian soil, across a rural highway from the GRU training base in Krasnodar. Utkin and another Wagner commander received military medals from Putin at a Kremlin ceremony in 2016, and Wagner fighters have been buried with military honors after cooperating with Russian military forces in eastern Ukraine and Syria. Adding further confusion, Putin said at his 2018 annual press conference that “if Wagner violates something, the Prosecutor General should evaluate them. But if they don’t break Russian laws, they can carry out their business anywhere in the world.”

Deir-el-Zour

Given this level of cooperation between the Russian military and Wagner, it was shocking that Russian commanders failed to halt a four-hour assault by a Wagner unit across the US-Russia deconfliction zone in Syria’s Deir-el-Zour province in February 2018. U.S. commanders, in constant contact with their Russian counterparts, called in air strikes that decimated Wagner forces. Wagner’s apparent goal was to seize a Conoco plant from Kurdish forces, in line with a contract Prigozhin had signed with Syria’s state-owned General Petroleum Corporation (with the support of the Russian Energy Ministry) that would give him 25 percent of the output of any petroleum facilities that were “liberated” for the Syrian government.

Russian commanders could have warned Wagner forces that a U.S. counterstrike was imminent, ordering them to abort the attack and withdraw. Instead they allowed them to be slaughtered. And while eventually the wounded were flown home on Russian military airplanes and treated in military hospitals, the Russian military even refused to send helicopters to the battlefield afterwards to evacuate the casualties.

As I have argued elsewhere, whatever other Russian motives were in play that day, the fatal outcome probably reflected infighting between Prigozhin and the uniformed Russian military. It followed a sudden drying up in 2017 of the weapons and salaries received by Wagner forces—and of Prigozhin’s military contracts. He had been the major military contractor in Russia since 2010, but in 2017, the Defense Ministry began refusing to pay Prigozhin, and four of his companies filed suit against the Ministry to have the contracts enforced (Prigozhin largely won). While it is impossible to prove, the Russian military may have been sending a message to Prigozhin in Deir-el-Zour. The message might have simply been that he was to keep his private forces out of their battle space. It might have been an act of revenge for his lawsuits. Or given what we know is a recent history of corruption in the Russian military, it might even have been a demand to give the commanders themselves a bigger cut of his contract spoils.

Whatever the reason, Russian military leaders have good reason to resent Prigozhin. He has no military background, yet signed a Syrian contract with Russian state support to undertake lethal action in Syria. He spent nine years in prison for organized crime activity in Soviet times. Yet in the early 1990s when Putin controlled business licenses in the St. Petersburg mayor’s office, Prigozhin opened a chain of fancy restaurants that Putin later patronized. When Putin moved to the Kremlin, Prigozhin became a very wealthy man—as the major caterer for the Russian public school system and the leading contractor for the Russian military. There is good evidence that Prigozhin cheated the military in his cleaning contracts, and the Russian Federal Antimonopoly Service rebuked him for engaging in fixed military contract bidding.

Prigozhin and Wagner After Deir-el-Zour

We might have expected that the February events would bring shame to Prigozhin and an end to Wagner’s foreign activities. Instead the opposite occurred.

Sudan

In November 2017, Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev oversaw the signing of a gold prospecting contract between Sudan’s Ministry of Minerals and a Russian company called M Invest. A firm by that name was founded in February 2017 in St. Petersburg for “extraction of ore and various non-ferrous metals,” and its director, Andrei Mandel, was earlier employed by Prigozhin’s military catering business. It is a good bet that M Invest is a Prigozhin company.

Meanwhile, a military correspondent for Komsomolskaya Pravda posted a video on Twitter in December 2017 that purported to show an unnamed Russian private military company training Sudanese forces. Multiple sources reported independently that this company was Wagner. Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir praised the “exchanges of specialists” from Russia who are “preparing Sudanese military personnel.”

Wagner may also be guarding the M Invest gold sites. But it is not clear that all Russian gold concessions in Sudan went to Prigozhin. As early as 2015 a Sudanese opposition newspaper reported on a different shady gold mining concession with a Russian company, saying a Sudanese consultant had abruptly resigned from the deal when he learned that the Russian company was “unknown.” In October 2017, yet another Sudanese state gold mining concession went to a Russian company called Miro Gold. (No company with that name is listed in the official Russian database of corporate registrations; the only business listed under the name of the owner of Miro Gold, Mikhail Putikin, is a St. Petersburg auto repair shop that closed in 2012.) In March 2018, five local residents were shot (one fatally) by Russian guards at a Miro Gold mine in the Nile River State of northern Sudan, when their two-month-old protest against the site turned violent. While some Russian media sources claim that the guards were Wagner, there is little evidence (outside the possible St. Petersburg link of Miro Gold) that Wagner or Prigozhin had anything to do with it.

Meanwhile, throughout 2018 there was discussion between Russian and Sudanese officials, including high-ranking military staff officers, about various avenues to expand defense cooperation.

Central African Republic

In December 2017, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov convinced the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) to make an exception to longstanding sanctions against the Central African Republic (CAR), allowing Russian weapons sales and Russian trainers into the country for a year to aid the government against insurgent rebels. In January, Russia sent in 170 civilian trainers alongside five Russian uniformed soldiers, and began training CAR military and presidential guard forces both in the CAR and in neighboring Sudan, according to a UNSC Panel of Experts report. The Russian state RIA Novosti news agency later reported (with photos) that Russians without insignia on their uniforms were also providing security for CAR President Faustin-Archange Touadéra and his retinue, although Russian officials told the UNSC that their presence was part of the training mission and not long-term. Yet Russian diplomat Valery Zakharov became the official national security adviser to Touadéra, and Russia announced that a five-person team (perhaps those uniformed Russian soldiers) would become a permanent advisory staff at the CAR defense ministry.

According to an investigation by the French newsmagazine L’Obs, the civilian trainers in CAR are employed by the Sewa Security Service, which is in turn the daughter company of a St. Petersburg firm (created in November 2017) called Lobaye Invest (Lobaye is a region just outside the CAR capital). White men wearing Sewa shoulder patches were photographed at a CAR training graduation ceremony in August. L’Obs wrote that the director of Lobaye Invest, Evgeny Khodotov (a member of a St. Petersburg veterans group) also directs a company called M-Finance, which is in turn connected to Evro Polis, the firm Prigozhin used for the Syrian oil contract. According to an African news service, in June 2018 Khodotov and Lobaye Invest were granted a three-year gold prospecting license and in July an additional one-year gold and diamond prospecting license by the CAR Ministry of Mines. While Lobaye Invest, Sewa, and Khodotov do not appear in the official Russian corporate database, an M-Finans firm was founded in St. Petersburg in 2015, specializing in “the extraction of precious stones.” CNN discovered that M-Finans shares an email domain name with Concord, one of Prigozhin’s military catering companies.

L’Obs reports that Sewa is also providing security for diamond mines in CAR where Lobaye Invest has the extraction contract. This information was later seconded by a CAR opposition newspaper, which reported that Prigozhin had a contract for gold mining in CAR as well. Le Monde repeated the claims and quoted an unnamed Western diplomat as saying that Russian troops in CAR had been deployed near mineral deposits. Two CAR participants at the Sewa training camp were also cited as saying independently that Prigozhin flew in by private plane to a negotiation led by Valery Zakharov between CAR and rebel forces in Sudan in August.

The Russian Foreign Ministry announced that “implementation of exploratory mining concessions” began in CAR in 2018, but did not provide any details about which Russian companies were involved. Three Russian combat journalists who tried to film a documentary about Wagner’s activities in the CAR were murdered in July 2018, and two additional individuals (including a former GRU officer) who tried to investigate their murder were poisoned (but lived).

Libya

In November 2018, Prigozhin was shown on video participating in a Moscow meeting between Defense Minister Sergey Shoigu, Chief of the General Staff Valery Gerasimov, and the powerful Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar. Haftar is a marshal in the Libyan National Army, which dominates the eastern coastal region of the country and periodically challenges the authority of the UN-recognized Libyan government in Tripoli. Prigozhin was seated on the Russian side of what appeared to be a negotiating table, near Shoigu.

Russia has been publicly supporting Haftar, perhaps in hopes of gaining his support for oil contracts. In October, a British tabloid claimed that Wagner was also working with Haftar, and while that claim has not been confirmed, Prigozhin’s presence at the Moscow meeting with Haftar was puzzling. Russian state news channels reported that he was there as the caterer of the event, and participated in cultural discussions with the Haftar delegation, but most caterers do not sit at the negotiating table.

Later that month, Bloomberg News cited unnamed sources as saying that Prigozhin was also involved in deals in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Madagascar, Angola, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe.

Closing the Circle

Amidst all of this, in September 2018, Putin passed a decree which officially classified as secret any information about individuals who cooperate with Russian foreign intelligence agencies without being directly employed by them. Commentators including Andrei Soldatov agreed that this was about Wagner, so that journalists who report about Wagner could be prosecuted for treason.

When all of this is put together, this is what we see: a convicted organized criminal from Putin’s hometown, who has prospered because of Putin, is now playing a leading role in Putin’s drive to expand Russian influence in Africa. Despite the 2017 military contract lawsuits and the evidence in Deir-el-Zour that the Russian military wanted nothing to do with Prigozhin, for the past year, the Russian state has been entangling the Russian military into what appear to be his business deals in CAR, possibly in Sudan, and now in Libya. These deals are shady: arranged through opaque firms and involving states under UNSC sanctions, and in the case of Haftar in Libya, a warlord. Meanwhile private military companies remain illegal in Russia.

We do not know what the exact relationship is between Prigozhin and the Russian command, either in Moscow or on the ground in Africa. But at a minimum, Russian military commanders are now in an exclusive club of people who are knowledgeable about, and cooperating with, Prigozhin’s shady deals. Either willingly or unwillingly they have been made complicit in his criminal activity.

Many analysts today are trying to puzzle out what Prigozhin and Wagner mean for Russia’s role in the world. The analysis here suggests, at least, domestic significance: Putin was able to demonstrate that he can mend fences between competing elites, in this case by drawing (or forcing) the Russian military into Prigozhin’s criminal orbit.

Kimberly Marten is Professor and Chair of the Political Science Department at Barnard College, Columbia University, and the Director of the Program on U.S.-Russia Relations at Columbia’s Harriman Institute.

[PDF]

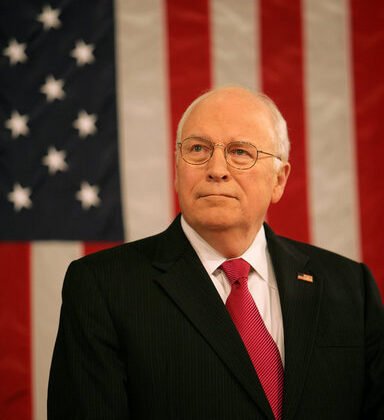

Homepage image credit.