The presidential succession in Uzbekistan following the death of Islam Karimov in September 2016 has rejuvenated discussion about the nature and future of Central Asia’s political regimes. Uzbekistan’s new president, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, has forged new relations with neighboring Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan and implemented some noticeable (though minor) changes in economic policy. In January 2017, Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbayev suddenly announced he would devolve some of his powers to parliament and published a draft of proposed constitutional reforms. How do we discern what are changes of façade in Central Asia and what are deep, structural, long-term evolutions? Six PONARS Eurasia members comment on the effects of leadership transitions in the region.

Nargis Kassenova, KIMEP University, Kazakhstan

Karimov is the second Central Asian “Father of the Nation” who died leaving a highly centralized and personalized system (the first was Turkmenistan’s Saparmurat Niyazov). However, no major changes occurred when they departed, which shows how sturdy their systems are. The authoritarian systems they built over decades became embedded through a framework of formal and informal institutions and rules. In Uzbekistan, the changeover from the acrimonious Karimov to the relatively benign Mirziyoyev gave rise to the possibility of improvements in relations with neighboring states and in the draconian treatment of the population — without changing or challenging the core of the system.

Karimov is the second Central Asian “Father of the Nation” who died leaving a highly centralized and personalized system (the first was Turkmenistan’s Saparmurat Niyazov). However, no major changes occurred when they departed, which shows how sturdy their systems are. The authoritarian systems they built over decades became embedded through a framework of formal and informal institutions and rules. In Uzbekistan, the changeover from the acrimonious Karimov to the relatively benign Mirziyoyev gave rise to the possibility of improvements in relations with neighboring states and in the draconian treatment of the population — without changing or challenging the core of the system.

Will Kazakhstan have a similarly smooth transition when Nazarbayev exits the scene? Unlike in Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, preparations for a power transition in Kazakhstan have been underway for quite some time. The process started with the adoption of the 2010 “Law on the Leader of the Nation” that gave Nazarbayev the right to shape policies even when retired. The process has reached a new stage with the recently proposed constitutional amendments that would transfer some presidential powers to the parliament and other government branches (there is also a provision to strengthen property rights). These preparations, however, are not aimed at a genuine power transition, but rather at retaining the status quo (“to change things so that everything stays the same,” as Italian writer Tomasi di Lampedusa said). Thus, instead of strengthening institutions and mechanisms of checks and balances, the Kazakh leadership is actually opening the door to incentives, time, and space for intra-elite power struggles. An important difference in the Kazakhstan situation is that its elites are more diverse, empowered, and consequently less disciplined than their Uzbek and Turkmen counterparts. The Kazakh system is more open, complex, and dynamic, making the challenge of having a smooth transition more difficult, but at the same time, the process may contain some promise for eventual political modernization.

Edward Schatz, University of Toronto

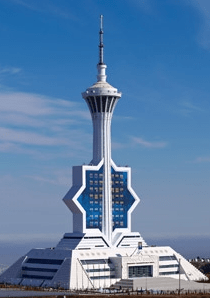

The excitement in Kazakhstan’s capital Astana (where I wrote this) is palpable. People truly feel that the president is preparing for succession. Since this is a president who cares deeply about preserving his legacy, he will try to ensure that it proceeds smoothly. Yet, his plan is not what it seems to be. Astana residents know not to take the apparent devolution of powers to parliament at face value. Rather, most agree that it is just the latest move designed to keep would-be successors off-balance, so that they do not challenge Nazarbayev’s authority prematurely.

The excitement in Kazakhstan’s capital Astana (where I wrote this) is palpable. People truly feel that the president is preparing for succession. Since this is a president who cares deeply about preserving his legacy, he will try to ensure that it proceeds smoothly. Yet, his plan is not what it seems to be. Astana residents know not to take the apparent devolution of powers to parliament at face value. Rather, most agree that it is just the latest move designed to keep would-be successors off-balance, so that they do not challenge Nazarbayev’s authority prematurely.

But there is no doubt that succession is in the air, and it is likely to be orderly. All of the globe’s geopolitical winds, including Western ones, are blowing in the same direction: for political stability and continuity, above all. The Kazakh elites seem to agree about what is best for them: accept a successor who will carefully steward the country’s macroeconomics and protect their political-economic interests in the short term. They will put aside their differences in part to honor Nazarbayev’s legacy and in part to protect their own positions. The risk over the medium term is that Kazakhstan will be ruled by, at best, a diminished version of the “Father of the Nation.” Nazarbayev has well-honed political skills that his successor may not possess. He also has enjoyed legitimacy by virtue of being the country’s first president and steering it through many a crisis. Elites have come to routinely give him the benefit of the doubt. Will his successor be so fortunate? If not, and if need be, what mechanisms will be in place to replace him or her?

The Nazarbayev transition will be extremely interesting. It will represent the passing of an era and many tears will be shed. But let’s not expect that the Kazakh boat will rock very much.

Eric McGlinchey, George Mason University

Age is but one variable in how Central Asian leaders conceptualize and respond to succession pressures. Equally, if not more, important are the threats that domestic protests pose. In cases where these threats are real, such as in Kyrgyzstan, leaders abide by institutional mechanisms that allow for dignified presidential exits and for some degree of continued influence. Elsewhere in Central Asia, protest is either nonexistent or easily repressed. This emboldens autocrats, even old autocrats such as Nazarbayev, to avoid properly addressing succession questions.

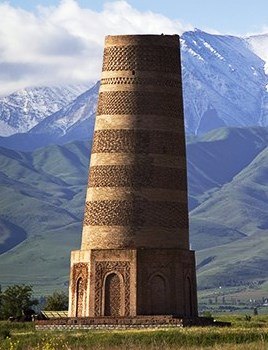

Mass uprisings forced out two Kyrgyz presidents (Akayev and Bakiyev). Kyrgyzstan’s third president, Roza Otunbayeva, made good on her pledge to serve as interim leader following Bakiyev’s 2010 ouster. Kyrgyzstan’s current president, Almazbek Atambayev, looks content to abide by his constitutionally-mandated one-term limit. Otunbayeva and Atambayev understand well what Akayev and Bakiyev did not: the power of Kyrgyz protestors. Otunbayeva and Atambayev assumed office with clear exit strategies. Otunbayeva resumed her NGO-development activities after leaving office. Atambayev appears set to return to the leadership of the Social Democratic Party of Kyrgyzstan. Paradoxically, in Kyrgyzstan, extra-constitutional popular putsches in 2005 and 2010 led to the constitutional institutionalization of the transfer of power.

Other Central Asia countries have also seen protests. Uzbekistan’s Andijan protests (2005) and Kazakhstan’s Zhanaozen protests (2011) were brutally repressed. Protests in Tajikistan (post-civil war) and Turkmenistan have not been on similar scales and any protests there were either repressed or allowed to fizzle out with little national media coverage. The Kazakh, Uzbek, Tajik, and Turkmen presidents, in short, do not face the same society-based challenge that their Kyrgyz counterparts must confront. What the other Central Asian leaders do face, however, are potential elite insurgencies. The likelihood for insurgency increases when the prospect of succession becomes realistic. Elites, when they perceive succession to be likely, are quick to shift loyalty to viable contenders. Autocratic presidents, as such, have strong incentives to dismiss any talk of succession.

The region’s comparatively young leaders — Tajikistan’s Rahmon, Turkmenistan’s Berdymukhamedov, and Uzbekistan’s Mirziyoyev — can credibly delay the succession question by tweaking constitutional term limits through popular referenda. What authoritarians cannot do is outrun death. They can, however, die in office. And just as alpinists might reflect on a friend’s passing — “he died doing what he loved, climbing in the mountains” — so too will we one day say of Nazarbayev that he, like Karimov, died doing what he loved, being an autocrat.

– – – – –

See Part 1 with commentary by Maria Omelicheva, Scott Radnitz, and Shairbek Juraev.